I V

O F

T H E

Q U E S T

O F

T H E

G O L D E N

F L E E C E

V I

If they did not keep to the oars, the east and north winds called Notus and Boreus pushed them back and threatened to cast them on the rocks of the shores. Yet the days of sea, fighting the wind without rest, took a grim toll on all of them. Argonauts began to collapse off their benches, and had to be left where they lay as the remaining Argonauts labored to keep the ship from drifting back dangerously toward shore and the pounding surf.

As soon as they did, they revived enough to climb overboard and make their way through the water to the beach, where they collapsed on the sand and lay as dead men for a while.

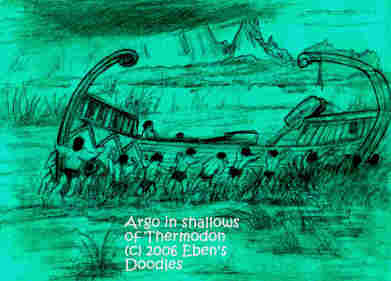

Unknown to them, this was the Isle of Ares the war-god that they had unwittingly invaded. They had no sooner got to their feet when the birds of Ares attacked (or at least they thought they were birds). Now this island had got the reputation it had due to the attacks it always made on anyone who dared land there and disturbed their nest. The Argonauts were no more welcome guests than other unwary travelers who had visited there. Out of the sky screamed bird-like things that might have been sicklebirds except that their wings did not flap and they moved faster than even diving eagles. Jason was armed, but the others were not, and they scattered into the nearby woods and swamps, for this was the mouth of the many-tongued Thermodon, which had innumerable islands and estuaries in which an army could hide and never be found.

Ares' war-bird made a single pass at Jason, but it was going so fast Jason did not even get a good throw at it, and it flew away unscathed. He got a good look at it, however, and was surprised to see it was part man and part bird--if a bird could be featherless as this one was and still fly like an eagle diving on its prey with tremendous speed.

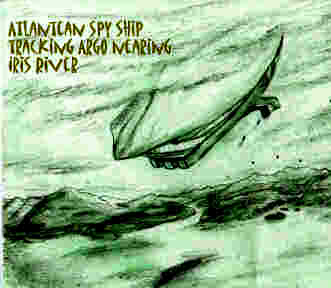

Jason stood looking after the war-birds as they soared away out of view. Had Ares whistled and called them like a man calls his hunting dogs? Such strange birds! he thought. They gleamed like bronze held in the light of a blazing fire, with not a feather to be seen. And the part that was man, it had a gleaming helmet, though which Jason could see eyes peering at him momentarily with the eyes of a man.

What an ugly, hateful bird! he thought. The look the man had given him was enough to chill his blood.

Whatever had called it away, Jason was glad it had gone. His javelin seemed a petty weapon against such a bird as this--which had a skin gleaming like burnished bronze.

Calling the Argonauts out from their hiding places, Jason got them back onboard the ship and they moved away from that island as fast as they could, even with blistered hands making their teeth clench as they plied the oars. Only when they were safe between reedy channels of the river, hidden from view, did they stop and catch their breath.

The moment he thought this, something seemed to strike his heart--he could feel a real blow--as if he had wounded himself somehow with an evil thought. What had he done? he wondered. Why should he feel so bad, so stricken inside?

Then he recalled something--Orpheus, singing that strange song of his when they all sat huddled under the sail, as if he were calling them to a quest greater than a warrior launched on a sea-quest of adventure and exploits worthy of the god Herakles! Then, all his crazy talk about a "One True God" and His Son, Prometheus the Fire-Bringer--it had made his insides churn at the time, and his head felt ready to burst! Yet... the way Orpheus had sung to them, he could never forget it. His musician's hands, no longer good for harping, no good for field labor either--what would Orpheus the Musician do after the quest was over? Though he had sung before kings and courts of nobles, he would sink into disgraceful poverty, he would starve and die a wretched, poor man in a hovel outside the city!

Thinking about Mopsos, then Orpheus, and all they had said and sung to him, Boreus's heart was deeply troubled. Once his life had been so simple, his plan sure to win everything he wanted in life, but now...now nothing seemed what he had first thought it.

"What do you mean?" Boreus wanted to know. Mopsos's remark seemed almost impious to his ears.

Mopsos gave his friend a keen look, then answered. "We all know of wicked men, and what they say and do for their own gain and amusement at other people's expense. They have added things, which are clearly not right though they amuse the shallow, embroidering the great tales of our people according to their own fancies. The great tales tell us what we need to know to seek and follow God aright--but wicked fellows have added many gods, and all sorts of evil deeds these gods of their making have committed with men and women. We do not have to follow such treacherous gods and their deeds. We can follow what our forefathers told us, which is true and noble enough in the main, and will still guide us."

Boreus was silent hearing this, thinking about the Seer's words for a while, though thinking serious thoughts of this kind was not what he had trained himself to do--nor had his fellow Achaeans ever been trained to think so seriously about life. He rose. He looked down at Mopsos, who was gazing toward the east just as Jason was doing quite often now.

"Are we really going to find this strange and wonderful treasure, the Golden Fleece of the winged ram of heaven that carried Phrixus from Orchomenus long ago to Colchis?"

"God willing," Mopsos replied. "Let us follow the man with all our heart, appointed our master by our act in joining him, and if we sail true to what we know, we shall not be disappointed."

Boreus, unable to contain his emotions, seized the closest javelin used for spearing fish, flung it high as he could at a passing flock of pelicans, then watched it fall and sink half way up the shaft into the mud. He walked away, back to the ship to finish his work on the hull. Talk was that they would be leaving soon, and he was excited, just as much as the others, at the thought they would soon quit the hot, muddy reedbeds of the Thermodon, with all its biting insects and dampness, for the healthy, bracing air of the sea road to Colchis.

Riding Argo's tall prow that once boasted a lion's head as mascot, two Argonauts got the first taste of the wonderful, cool, salty air, and after the steamy-hot miasmas of Thermodon, it seemed to them as delicious a honey as with open mouths they drank it in.

Taking personal charge, an Atlantean prince who did not like the idea of Achaeans gaining the upperhand in a world that was being reconstructed to prepare for their own return and the pre-eminence of Ilios and her goddess, viewed the Argo's survival as a growing irritation. He decided not to execute the man he had replaced--not now anyway--and instead concentrate on the best way to eliminate this annoying little Achaean expedition which was threatening to advance the Achaeans' power beyond which their plan permitted.

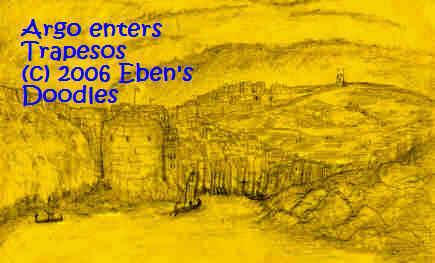

With the tattered but still serviceable sail, the Argo now sailed like the true sea-going vessel she was--straight and almost effortlessly to Trapesos.

Jason was at a total loss. How did these thousands of Trapesians know anything about them? What had they been told? What had provoked such a great outpouring of the people's love and acclaim of them? What had they done to deserve such a reception as this? And, if they had been awaited, as it seemed now, why did no one escort them in to the harbor? Was the utter surprise intentional?

He and his fellow "heroes" soon found out the answers to some, if not all, of these mysteries.

Jason was almost reluctant to pull close to the docks, which threatened to spill dozens of the most eager youths into the water as they clung to every post and pillar, each striving to be first to touch the Argo or leap aboard.

Furling the sail, they oared the rest of the way in, seeking a berth at the docks which were crammed with the prows and sterns of dozens of ships of every city and kingdom around the Unfriendly Sea.

But they did not even reach the nearest dock when Trapesians, like fish emptied from a swollen, bursting net, leaped into the water, unable to bear the wait. The Argo was soon mobbed by wriggling swimmers, who clung to the oars, pulling themselves up. It was chaos, the hundreds of Trapesians threatening to capsize and swamp the Argo--but Jason could do nothing. He had seen nothing like this--and his father's description of the city had given him no warning of how extremely hospitable it could be.

When the Argonauts climbed ashore, "helped" by Trapesians, who could not be prevented from hoisting each of them up on the shoulders of the strongest young men, they were rushed to the agora just beyond the docks.

Here, above the heads of the people, Jason saw a regal-looking man, attended by soldiers, waiting for them. But the crowd could not be controlled at this point. The whole city was beside itself for joy at their arrival. Musicians were all playing at at the same time, garlands of flowers were draped round the necks of the Argonauts, and they were paraded, on shoulders, round the agora as the crowd thundered with applause and cheering!

It was unbelievable to Jason and the Argonauts! What madness it all seemed to them, but they were powerless to stop the rejoicing.

Bewildered, Jason heard a splendidly dressed official from the palace invite them to the king's presence. As the king could not reach them for the press of the crowds, he would return to the palace and wait for them there, as soon as they could be carried up.

The crowds seemed to guess the official's mission, and they celebrated all the more, as if to prolong the Argonauts' presence with them.

Soldiers and palace guards pushed through the people, however, and the crowds reluctantly gave up trying to detain the visitors from being received by the king.

Jason lost sight of the Argonauts, as each was transported to the palace, surrounded by hundreds of escorting citizenry.

As he was let down to his feet, he realized that this was no small city and modest palace such as his own native Iolkos. Trapesos was no longer a town with a little fleet. It had grown large as Miletus or Tiryns since his father's visit. The houses were many-leveled, with fine gardens, all wealthy in appearance, and the people well-dressed, wearing gold and jewels that seemed common here and of little value. Surely, it could launch a thousand ships, if it wanted to buy them or have them built.

In the king's hall, after a great deal of escorting by massed soldiers, Jason at last stood before the king, Gorgas.

Jason touched it lightly, then bowed deeply, but the king took his hand and led him to the throne, and bade him sit.

Jason was shocked. What king had ever invited a stranger to sit upon his royal seat? But Gorgas insisted, and Jason could not offend his host, and he sat. The king then drew off his royal mantle and put it round Jason's shoulders. His golden, jeweled diadem too, he placed on Jason's reddening forehead.

This was like a dream, gone too far, and Jason would have protested, but the king explained. "Noble youth, rule in my stead, king of this pleasant city for these glad days of your visit! Anything you wish, it is yours! It is an honor for us--the greatest honor! We are in present peril of an attack by Colchis who will take or destroy everything you see--and then you come to grace our sad-hearted city with your presence, to give us heart and strengthen us, O Heroes of the Achaeans! That is why the people, and their king, love you so greatly!"

Jason now understood, the tears of revived hope and joy in the people's eyes--the shouts of love that far exceeded anything they could possibly have earned by the greatest deeds or exploits of bravery--they were viewed almost as saviors, as deliverers, from the city's imminent capture and destruction--though they knew they would soon be leaving their beloved city for a barbarian land in the north.

The king continued.

"We are not expecting you to leave your venture and stay and fight with us against the Colchians--but only stay, if you please, a few days at least, and we will feast you and celebrate your coming--"

"But how did you know of us, and when we would arrive?" Jason burst out.

King Gorgas laughed. "We have many eyes and ears serving us in various ports and cities along your long route, but your own uncle the king sent word too--not to us, of course--for he heartily envies and dislikes Trapesos--but to that cunning lion, that hateful bear of the tall western mountains, Aeetes, which word was given us by a little white-winged messenger!

The king paused, and a little scroll was handed him, the length of a fingernail, which he then rolled out to an amazing length despite its size. A court scribe then read in thundering accents, the great communication.

"Peleus of Iolkos, the high king of the great allied peoples of Minyas and Achaeus, and favored son of the gods, sends urgent word to our friend and protector, Aeetes, king of towered Aea--beware of the naughty youth, Jason, with one sandal, my nephew! With his ship and bad, unruly companions, he seeks glory and adventure--and the thing called the Golden Fleece! Let him have the fleece of the winged ram Phrixus sacrificed, I pray, with whatever great difficulty or sore test you devise--only keep him from returning here to trouble me further with his demands. I will send you a present of fine Knossian craft, in exchange for his sandal and his foot still in it."

The king's eyes glowed. "You are our dearest friend and ally, if such a low, and treacherous creature as the writer of this scroll is your enemy. And where you are going, you will need friends, will you not? Many youth here, with brave hearts such as yours, will want to go with you, but I will tell them they must not burden you and your ship."

"Oh, no, O king! Let them join us! We lost half of our elect company, devoured by a sneaking jackal in sheep's clothing, and this is the best gift we could wish from you! Only they must be brave--and strong in limb. We have found much toil and trouble getting this far, and worse is to come, I expect."

The interview went on, but by now the rest of the Argo's crew had arrived, and they were then released to their quarters, for baths and changes of clothes. Each was given two changes, of the very finest quality.

Led to the king's own bath, they quickly made good use of it.

Outside the palace, the city continued to celebrate long into the night. It was some hours into the morning before it grew quiet, and the Argonauts could find sleep after so much excitement.

The next days were filled with games and feasting, all staged in honor of the Argonauts.

With the king by his side much of the time, Jason had opportunity to ask him more about the city's trouble with Colchis.

"We have fought them off many times when they send raiders--and often won their ships as prizes, but they are going to send the main fleet now, to reduce us to their abject slaves. Why they don't trade peacefully with us, I do not know. Perhaps, we have grown too large and wealthy of late, and they are fearful we might go and attack them someday? Yet we only want to be friends with them, for we have enough good country of our own, without trying to seize theirs with much bloodshed! Of course, we cannot fend off so large and greedy a kingdom as Colchis, and we refuse to be his cringing slaves, so we will let him have this city our forefathers founded ages ago. He will gain nothing of value, for we are leaving in our ships and taking our treasures, and will burn everything else--houses, docks, towers, orchards, even our farms and crops, along with whatever cattle or small livestock we cannot carry away. Nothing must be left for them to gain thereby for their great expense in coming."

"Where will you go?"

"Far to the north, on the western side of Cheronnesos that faces the coast of the River Ister--a land where there are no cities and the barbarians will likely come to trade with us. We have plenty gold, so we will trade it for their fine grain, and then sell the grain in Miletus and Pylos and Tiryns and such cities, and so we will make a good living again by and by. It will not be easy for us, having to build a new city on that cold shore where the North Wind is king--but we will not be Aeetes's slaves!"

It went as the king decreed--the next days were spent with feasts and games-- and the games at which the Argonauts excelled time after time made the Trapesians love them all the more.

Orpheus was carrying a harp again, a gift from the king, but it was Boreus who was being taught by the Musician to play it for him.

Orpheus, who knew the dances best, coached the Argonauts, and then they performed them almost flawlessly, to the spectators' delight.

In one dance two Argonauts dressed in full battle armor danced to the Thracian flute played by Orpheus, leaping high and spinning first one way, then another in the Thracian manner while swinging their swords. Then one struck the other in his belly with his sword, who fell and appeared to die, and the victor took his sword, shield, javelin, helmet and armor as spoil while chanting the glories of his native city and her long record of victories in war.

When the fallen man popped his eyes open and leaped back to his feet unhurt, the crowd went wild, since they had thought the man was dead, but it was only the great art of Orpheus, who knew how the cunning Thracians had performed this great dance and made it so true to life.

The first dance whetted the appetite of the Trapesians for the next, which was even better. Argonauts began with dancing the popular karpeia, and then after this introduction, one of them laid aside his weapons and pretended to sow a field and to drive a yoke of oxen which plowed the ground he sowed coming behind. How the people laughed as he looked around with big eyes, showing great fear as he sowed the seed grain from a bag slung around his neck. What was the matter with him? Everyone was intrigued to find out. Soon they knew. Interrupting the busy but wary farmer, a howling robber leaped at him, and they fell fighting furiously like two wildcats, tumbling across the ground. All the while the flute is playing a wailing, whooping melody, and then the farmer gets the advantage, binds the robber so he will not be any more trouble that day (and maybe the next too), and departs, driving off the oxen while hailing the cheering crowd.

Back in Iolkos, he had had no idea Aeetes was such a hated and feared tyrant, and now that the Argo was nearing the borders of Colchis, it was looking to him like they were sailing into the jaws of a lion.

Was Aeetes really so formidable as his neighbors described him? Well, even if he was, Jason decided, they had not come this far to turn back. He was determined not to lose his ship and his men--except that he had no control over storms and the attacks of sea monsters and such. But should he hazard his ship and men against a known enemy--such as Aeetes now seemed to be? Was the Golden Fleece, and the glory that would be theirs if they brought it back to Iolkos, worth the risk of all their lives? What if the king decided to arrest them, seize the ship, and throw them all into his dungeon--to languish there unil they died? The wicked king would have a stiff fight on his hands if he tried that, of course--but fighting a king holding an army and a fleet was unthinkable. What was the best thing to do? Before they sailed, he would put it to the men in a council, he decided.

His left foot paining him terribly, Jason sprang from his bed, and his whole body shook, covered with sweat. He fully expected to find the snake and its separated head still twitching and hissing at his feet. But the marble palace floor was bare--dimly lit by moonlight sliding through a window high in the wall. It was only a dream! The red, burning star, then the serpent in the tree that bit his foot--they were only bad dreams! Yet why did his heel still throb with dull pain as if he had bruised it?

Jason, trembling with cold, went and covered his body with the bed blankets and massaged his foot with his hand, but still he could not get warm or make the pain go away entirely. He sat up, thinking about what he had dreamed. What was their meaning? Two dreams, yet they seemed connected somehow. In the morning light, he rose early, and went limping to find Mopsos, to see if he could possibly tell him the meaning of the two strange dreams.

"I know who you are! We have been waiting for you to come, more than the city waited for you. My boys are the reason I must speak to you. Is there a more private place?"

"No, but my comrade will repeat nothing he hears from you. What is it?"

She seemed to hesitate for a few moments, then looked him determinedly in the eyes. You sent my eldest son away, as if he were a liar. Why did not believe him? I have come to tell you the truth. These are all grandsons of Phrixus, whose glory you have come all this way to seek and share, if you can win it from the tyrant in Aea! I am here in this city, only because of him. He would kill me and my sons, just as he killed Phrixus's four sons, their wives, and their children, if I had not fled on with my boys, covered with a sailcloth, on a ship returning to Miletus. I knew I would be discovered on a long voyage by Aeetes's spies sent out to seek for us at every port, so I thought, best hide close by here in Trapesos, where he will least expect me. Here we have been safe enough, with the king's protection. But I have little I brought out from my home--just a pot from Phaistos, and this royal mantle Phrixus gave his eldest son, my husband whom Aeetes killed.

As if divining his thoughts for her, she said,"Don't mind me. I am leaving with the people and following the king north to some new site--anything to get away from King Aeetes and his spies! But my sons--take them please! I will rob them if they go with me--for they will not gain their father's inheritance in Orchomenus, and will be poor as I am--despite the king's kind charity. They are far safer with you, seen as your sons whom you and your men will defend, than they are with me, even in this city. Will you take them? I have only this fine vessel to give you in payment."

She drew out from her long cape a magnificent pot from Phaistos, from the royal workshop of the palace. For such a treasure of art a king would pay a great sum, Jason saw at a glance, but he thought of a better use.

"May I see it, O lady?"

She immediately held it out to him, and though it was a stretch he got hold of it.

After filling the vessel with a fortune in gold, he handed it back to her, and she looked at him, surprised by its great weight.

Jason smiled. "Keep the vessel for yourself, it will earn you many a gold piece. I will take your sons as wards! Do not fear for them. I vow to you, on my name and my father's honor, that I will bring them all back safe to their grandfather's home and family in Orchomenus. There they can receive the inheritance due your husband and his sons. And there they can send for you, so that you can join them in their good fortune and see your grandchildren born to you."

The mother and widow did not waste any time. She bent low, spoke something to each boy, and they stiffened manfully, with tears in their eyes. Then, without even a caress, she dropped the warm woolen mantle fit for a king into the hands of the eldest and taking the vessel of Phaistos walked swiftly away, as Jason gazed after her with amazement. He turned around and found Mopsos gazing at him.

"Well, what would you have done in my place?" Jason burst out.

Mopsos smiled, as admiration shone in his eyes for his Trapesian-crowned captain. "The same, O King, " the Seer replied in his laconic way.

Usually nonplussed, no matter what was happening, this time the Seer's jaw dropped open.

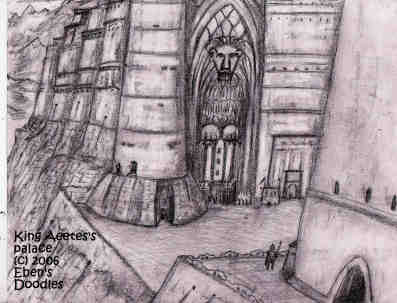

Despite a loving, obedient daughter who worshipped him as if he were the best father one earth, he was capable of any cruelty toward man or beast. King Gorgas had even told him that Aeetes' servants attending his sleeping chamber were always in great hazard of their lives--for the least thing that didn't please him was cause for him to throw his big bronzen water jug at their heads--and if he missed braining some poor servant girl to senselessness or death--he would grow all the more enraged and grab his sword and gash a wolfhound chained to the foot of his bed. The royal kennels were hard put to supply him with guard dogs, in consequence of his many rages--and after his frequent attacks on them, the terror of the dogs was such they had to be bound and dragged in to his chamber, for no stall in the kennel would could keep them very long. Somehow they would break out and run themselves right off the cliffs of the palace heights.

The wretched tyrant lived in constant fear of assassination, so that he seldom, if ever, slept in the same bed chamber twice in a row. That was why the palace was always under construction--new bedchambers were always being built, until now he must have a thousand places to sleep, and more high towers and well-stocked arsenals and soldiers added to guard them.

He also permitted no pillows whatsoever on his royal bed, having an evil premonition that he might someday fall ill and helpless and be murdered by his attendants smothering him with the pillows off his bed.

Poison was uppermost in his mind, too, so he permitted no morsel of food, and no drop of wine, to touch his lips until the food and drink were first tested by his Cupbearer and Chief Baker. If they did not turn ashen-faced and drop to the floor clutching their bellies and writing in agony, he then knew it was probably safe for him to eat and drink the same food and wine they had just sampled.

Nothing was so strange, however, as his habit of growling and chewing the edges of his carpets when he grew so angry he turned into a kind of beast or wolf. His chief officials had all witnessed him behaving beastlike as he crawled about and clawed the floor on his fours. Despite this, his daughter was reported to refuse to hear a single word about it. She believed with all her heart that he was just as high and holy a monarch as he took pains to present to her whenever she was in his presence. In her image of him, he could do no wrong. Even if the whole land sweat blood, or the moon cause cows to birth human-headed dragons and other atrocities, she would never ever think him the cause. Instead of reason, which the Achaeans much preferred above life's pleasures and even placed over the crowns and scepters of kings, she chose loyalty--"the king, do or die!" For her, it was sufficient to blame his ministers for every atrocity committed in his reign. In her eyes, he was innocent and just in all his acts.

When the men heard this report, particularly the sad news about the sons of noble Phrixus, they were greatly sobered, realizing that a king who would dare such a crime would probably not hesitate taking their lives too as mere candles are snuffed out--the moment he pleased to do so.

After that report sank in, the Argonauts forgot Jason was even present and freely began to vent their feelings and thoughts about whether to continue or not. Talking things out in this manner was the best thing, he knew, to grumbling and fearful insurrection on board the ship at sea! If there was a divided man on board--they were all in danger--as he knew full well, even before the base traitor, Lukeios, had darkened the fair Argo with his evil presence!

He saw he had no need to give them any more details of the information given him by King Gorgas--such as how the king had whole rooms stuffed floor to ceiling with golden, gem-encrusted shields and swords, while taxing his Colchian people to the most wretched depths of starvation and nakedness.

The king's gold-lust could not be satisfied, it seemed. He was forever scheming how and when to attack his neighbors in their cities or kingdoms, to steal their wealth for himself, just so he could hoard it in his fortress palace high over his capital, Aea.

One after the other Argonauts gave views on whether they ought to confront such a monster of a king in order to seek the Golden Fleece. The council was a heated one, as the subject was a matter of life and death--their lives and possible deaths!--and nobody was counted anything but equal in reason in the assembly--and so whatever was thought worthy to be said by any man was given a respectful hearing by all.

This was what Jason wanted to see in a council.

The Achaeans were, of all peoples, free men, able to speak their own minds--without having to told what to think. No man, even if he wore a crown and had many soldiers, could make an Achaean think the way he demanded. Achaeans would die, rather than submit like a dumb animal or a slave to its keeper's rod. This was the chief thing that made Achaeans different from every other tribe and nation of men--they loved to think freely and inteligently, and were not afraid to say what they thought. If was not enough, though, to express one's thoughts--they must be given evidences, proofs, by which good thinking is distinguished from poor, faulty, spurious thinking. Any fool thinks, but he thinks poorly, without any foundation. No Achaean admired the spouting fool! Rather, Achaeans pelted such fellows with rotten fruit if they wouldn't shut up! Achaeans did not suffer fools for very long. All men were free to speak their minds--but not stupidly, wasting people's time and patience. Even worse than stupidity to the Achaeans was lying. Liars were not thought clever fellows. Liars were stoned--with real stones, not overripe figs. The truth was loved by the Achaeans, so much so that anyone who offended, by not telling the truth, was considered an enemy of the city--and was driven out of society, having shown he was not fit to share the society of civilized men. Since kings even ran races yearly, to prove to their subjects that they were fit to continue in their reigns, so everyone was expected to train and nourish his reasoning power, for the good of all.

Civilized cities were judged those that welcomed the free exchange of ideas, about which no one was forced to agree--except those that were necessary for the preservation and health of the city. Traitors were stoned to death, without much of a trial, since treason was counted the most base and senseless thing a man could commit against his own people. Outside of treason, they were not at all displeased to hear what they did not agree with--that made them all the more interested, in fact, when someone did not agree so that they could try to persuade the man to join their way of thinking, without force, but with superior reasoning.

The man with superior reasoning was the hero they most admired--just as much as they admired champions who could fight or win at some test of strength, courage, or skill.

Achaeans were thrilled whenever a man demonstrated in word play that he commanded the superior reasoning power. In this sport--which was held in greatest esteem, even over the physical contests--a thoughtful farmer could perform as well as a man of the city, a tradesman as well or better than an official or nobleman in a mansion. It was superior reasoning, the Achaeans held, that proved the true worth of a man--not his wealth, or social standing, or whether he was handsome or ugly, old or young.

So Jason listened intently, not saying another word. As for himself, he would not ever change course, or cut and run from his quest of the Golden Fleece. It was his destiny, he knew, for which he was set on the wide and wonderful earth, and he knew he would achieve nothing by not staying the course he had set for himself in Iolkos now far away across the wine-dark sea.

The government of the Argonauts, then, commenced, and each man was expected to speak his mind regarding Jason's opening statements. The proposition was understood--whether they should proceed or not on the quest, since their host in Colchis was now known to be a murderous and evil-minded beast.

Some favored going ahead anyway--excited by the challenge. We are stronger, we are smarter, we are trained to fight well--so their thinking went. Some not so foolhardy and sure of their advantages favored turning around at Trapesos. They said such things as: we may be strong, but we are not superior in numbers, and the king has a big army, and he may be just as smart as Achaeans and have his own champions trained to fight them--what then? It was best to not risk their lives against such odds. Still others said differently, trusting to good fortune or the favor of heaven: "We do not really know what may fall to our advantage, unless we go and try the waters--and if we try, perhaps the gods will favor us over them--since they are oriental slaves, who do not have the advantage of free men such as ourselves!"

No one course of action--to go or turn around, or even to take their chances--gained the upper hand with superior reasoning. The Argonauts looked for someone to break the tie. They had forgotten Mopsos, who had taken the grandsons of Phrixus to the bow, and was teaching them some things about casting fishing lines.

"How about you, Seer?" an Argonaut called to him.

Mopsos heard him, said something to the boys, and he went and sat down.

"What is the question put to me?" he asked. Ancaeus spoke for the others. "We wish to know what reason you have for going forward, or, if not, why we should turn around here at this city and return home."

Mopsos looked over the council. He wanted to know if they wanted his words, or if they were just wanting to argue and debate. If they wanted to argue cleverly with words, or quibble over shades of meaning, he was not interested to join in, but if they were serious about true things and discovering what they were, he was willing.

Apparently, what he saw, told him to go ahead. After all, no Achaean worth his salt would ignore a man with an honest, open mind seeking the truth of a matter.

The next few minutes, as Mopsos spoke, there was a hush that only his voice broke--for no one had ever heard such thoughts, nor had they ever thought them--this was all new, the world he set before them. For he started with a story, describing a traveller out to seek his fortune in the wide world, having left a poor, rocky country where he could not make a decent living and life for himself. This man climbed down a high, snowy pass into a rich, well-watered, most beautiful valley spread out before his gaze. Would he continue, or not? It was truly a decision that might cost him everything, even his life, for in the lush valley lay a great number of difficulties and snares, and giants who would rise to defend it and rush to kill any intruder.

"Well?" he turned to them all, pointing. "What is your answer, yea or nay?"

The Argonauts, captivated by the beauty and potential of the valley, all said Yea!

Mopsos smiled, but his eyes were not smiling. "You do not know what you are asking to happen to you! Let me tell you then, as you asked me to speak. Only this time, I will lay aside the story and speak plainly."

It is the change in our hearts and minds, in our souls, that will tell if we are men or brute animals. The light is dying, a light that shone more brightly for our forefathers.

Now it is it fast fading, growing dim--but we fill our eyes with the good things of our new lands and new homes and cities and ships, and the shine of them replaces the true light we need to be a living people. We are becoming a dead people, living like animals, for when the light dies out in a people's heart, soon other people will come in and take what they have, for no man can fight for what is his once the light goes out in his heart. That light does not come from him--it is given--and it makes him a man. Once you let it go out--it cannot be relit on the old wick--or with the old oil--it is dead!

Will you too lose your light and stumble into darkness and go down to Hades forgotten in the dark kingdom? There is a better world, a future and a hope beckoning to us men, but you let the light go out in your heart--and missed it. You went with all the others who let the light die out in their hearts, following them to the dark kingdom."

"What harm do you fear, comrades? I have heard all your good speeches. Don't you know that it may be expedient for one to die--if necessary--to save us all from a terrible fate not one of us will escape? Yes! I know this man who would die for us. You know him too. He will die, if need be, to save all of us. So why fear for ourselves?

"Let us play the man in this quest, my fellow Argonauts! Win glory forever, instead of shame. We can all win the Golden Fleece following this man Jason. He will never turn back. He will go before us--never doubt it. A few more days and we shall set foot in Colchis where Phrixus sacrificed the Winged Ram from heaven and where his golden fleece hangs in a tree to this day. Our forefathers knew this, and told our fathers, and they told us. All of this is true--though the gods be liars, and the priestlings who serve them in the temples be wicked men! This is the light of which I spoke. We must be true to it, or it will leave us to stumble away into darkness."

Mopsos fell silent. The Argonauts were silent too, everyone thinking about his words, which many realized were great words.

The next morning, early, before dawn as was his custom, Jason went aboard the Argo, and every man who had heard the young but wise Seer's words, challenge, and admonition, also went aboard, their brave hearts beating with anticipation. For them there was no turning back, a noble decision that put strength into every double-sized oar as it plied the water out to open sea where the the west wind would fill the sail.

For all the Argonauts, the prize was worth every sacrifice, every pain, every conquered fear, and Orpheus on return home sang of the Fifty and their Quest, with Boreus playing his harp faithfully, as they traveled forth through all the cities and islands and ports of the many-shipped, far-sailing Achaeans. Everywhere, celebrating people heaped flower garlands and praises and special gifts upon them and all the other Argonauts. Shrines were erected in the home cities of those who did not return home--shrines even for those with shameful ends--their glorious beginnings remembered instead of their shameful ends. Such was the way of the generous-hearted Achaeans of that time.

It was a wise saying of the old progenitor of the Achaeans, who said of his brave-hearted, sea-faring family: "They that go down to the sea in ships, see the works of the Lord."