V O L U M E

I V

C H R O N I C L E

O F

T H E

G R E Y

D O V E

A N N O

S T E L L A E

1 8 7 8

Wings over Te Aute

The Island of the Long Cloud was really two very large land masses, and composed of many powerful chieftain-ruled principalities—much like Japan to the far northeast. As long as the islands and their patchwork of Maori tribal kingdoms remained isolated from the outer world, things continued the same century after century in its warlike, clannish society.

But technological advances in Western Europe empowered Europeans to begin an unstoppable conquest and colonization of the whole earth. The Island of the Long Cloud, along with the greater islands in the north and a thousand miles to the east, were in time to experience a first, epochal visit by white-skinned “Europeans.”

The visitors came on strangely configured Great Canoes, that piled sail upon sail upon sail into a mountain of sails, all used to propel the canoe forward in any kind of sea or weather. What was more interesting than the unnecessary waste of sails, to the thinking of the Maori, was the arms of the warriors aboard. Maori were always fighting. They loved warfare—though they had taken thought never to make it so fierce that everyone was killed on the losing side and all the houses of the pa were destroyed.

What would be the good of that? They reasoned. Kill their chief warriors, maybe even their chieftain or king, and that would be enough victory for anyone to enjoy. The following year, war could be made again by the opposing villages or kingdoms, without much harm to either contestant. War dancing was very important. Looking fierce, acting fierce, were highly valued postures in the war dances—but indiscriminate slaughter of the enemy was unthinkable.

After all, they were all Maori on the Island Kingdom of the Long Cloud.

The Europeans changed the whole thing from the start with their stupifying armanents. The Maori found that the Europeans could launch many ships, fitted out with monstrous, thundering, fire-spitting pipes that shot giant balls of stone or iron.

Nothing, no wooden, bone-plated shield or chief's flagship hull however thick, could stop such projectiles. Terrifying the Maori because the pipes could thunder and spit in the darkness of night as well as in the day, they destroyed everything in their path.

The Maori also found out that the European white people also possessed clever hand-held pipes of various sizes that thundered and shot small balls of metal that pierced every kind of armor the Maori possessed. These balls of metal were pointed like spears and sometimes flew right through a man’s body as though it were made of air.

Often they killed a man outright, before he could even fall and strike the ground, which was hard to do even with an expert spear thrust.

That was how deadly the Europeans’ weapons were. Equipped with such things, the Europeans thought nothing of slaughtering whole tribes and villages if anyone opposed their coming in and taking away the people’s lands and goods.

Before the Maori could put aside their age-old differences and rivalries, the Europeans had gained so much ground that they could not be thrown back into the sea. Fighting against superior weapons, the Maori were slaughtered, and the last of the tribes made peace with the white people. Some tribes freely sold their lands to the white people and refused to fight for them any more. Having much money with them, the white people gladly bought up tribal lands in this way, sparing them the trouble of going to war for them. Yet if war broke out, they won and the land fell to them anyway.

According to the treaty they were obliged to sign, the Maori received a portion of their country in the northern island—that was all. Everything else became the possession of the invading white people.

It was a dark day for the Maori, who understood war, but not this kind of unconditional warfare, where one side took everything, or virtually everything away from the defeated side.

In the later days of the wars against the Europeans, it was likely that one side would surrender before others were ready to do so and sell off their lands, and so it was that the tribe of Chief Te Hapuku had a falling out with the tribe of Chief Karaitiana, because Chief Karaitiana decided to fight no more and lose his people and lands for nothing, while Chief Te Hapuku wanted to fight on, just to see if that was the better way.

Chief Te Hapuku never forgave Chief Karaitiana for giving up so soon, before he lost all his warriors and had only women and children left in his pa. He attacked Chief Karaitiana, and in the bloody war they lose many warriors on both sides, gaining nothing from the conflict, which weakened them before the white people.

As for Chief Te Hapuku, he went back to war against the white people and was defeated so badly that he lost all his sons, and most of the sons of the women of his pa also lost theirs, so that it was a mournful place in his remaining years after he was thrust by the victorious white people upon the Maori reservation land allotted to him. The loneliness, added to his crushing defeat, greatly embittered the chief, and he would have nothing to do with his former friend, ally, and fellow chief, Karaitiana.

Twenty five years passed and Te Hapuku lay dying on his bed in his pa at Te Aute Lake.

Sir George Grey, a white chief who though Premier of New Zealand had tied himself in friendship to Karaitiana, heard of Te Hapuku’s imminent death. He told Karaitiana, and the old chief mourned to think that they had warred against each other in their youth and never had renewed their Maori vows of kinship since they disputed concerning the sale of the rich country between Seventy-Mile Bush and Napier.

Many noted warriors had fallen in the dispute, which had excited the spirit of revenge greatly at the time, but now everyone with Karaitiana mourned for the dying chief, including the white chief.

It surprised everyone when the white chief not only mourned with them but vowed to bring the two war chiefs together. They once were friends, who had loved each other like brothers. Why should they part in death like enemies? the white chief challenged Karaitiana. Such a thing was no good whatsoever. Something must be done—and soon! They must rub noses, for the last time!

Karaitiana consented to go with Sir George in his carriage the forty miles to the tribal lands of his former bitter arch-foe, Chief Te Hapuku. Both men, entering the territory of the hostile and well-fortified pa, could have brought warriors for their own defense, but the white chief left all the warriors behind, both Maori and white. Alone they rode into the domain of Chief Hapuku, and, fortunately, no one opposed the “paheka” and his friend Chief Karaitiana.

Reaching the kaingwa, the village where the people normally resided, they still met no opposition and slowly proceeded between the houses to the plaza known as the marae. Here the meeting house stood, but apparently the chief was not in attendance, for there were no people in it. Realizing that the chief was in the fortified pa, the only proper place for their chief to die, Sir George gave order to move on.

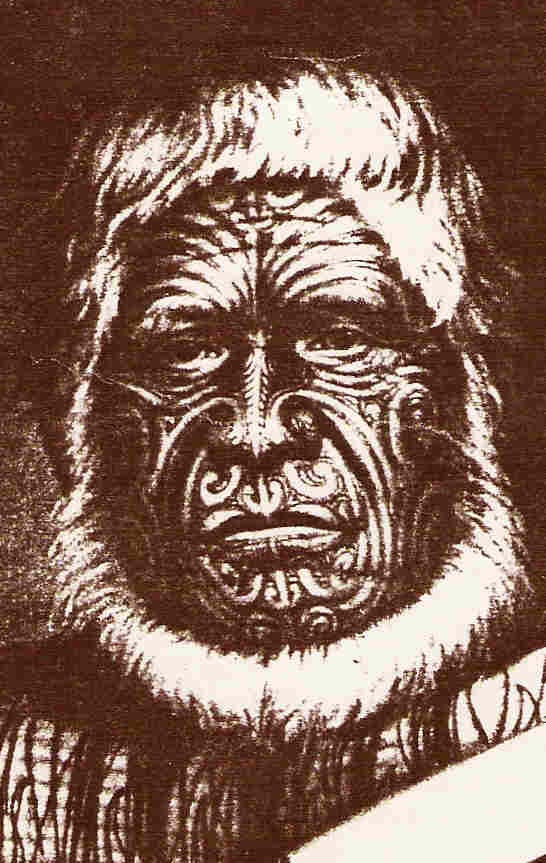

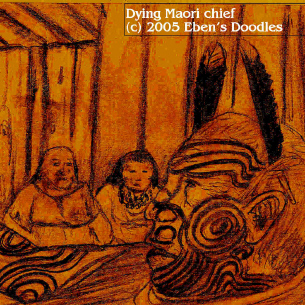

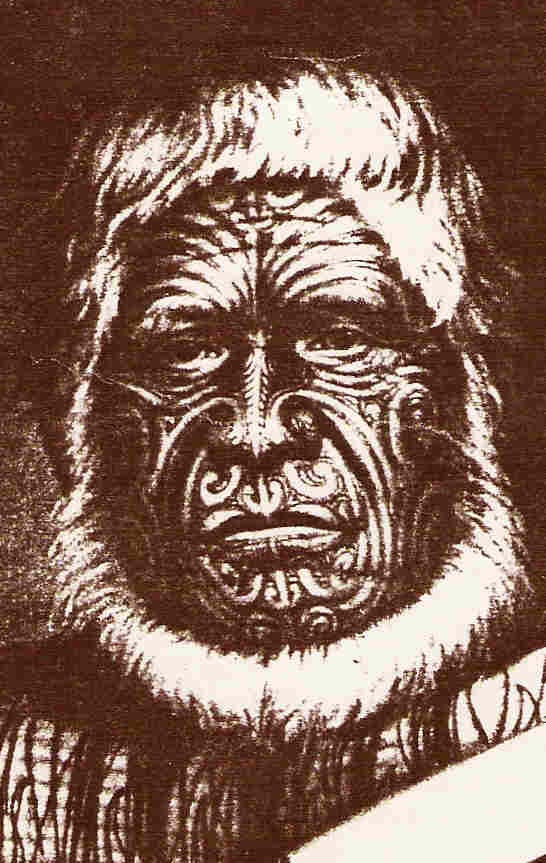

As a big crowd of mostly naked but intricately-tatooed men, women and children gathered round them, they found word had proceeded them and they were escorted to the palisades and main gate of the pa. Never could they have reached it alive even with troops, for the earthworks and the palisades would have thrown them back, along with the spears of over a hundred warriors. Here they got down from the carriage and, escorted by warriors, Sir George and Karaitiana were led into the inner room where the dying man lay, his women mourning for him already as they sat off to one side.

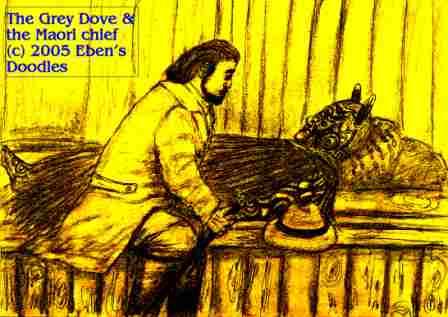

Grey went to the chief's bedside and sat.

Normally, no one could do such a thing--but the chief was not angry, it appeared, and none of this household dared then to kill the chief's white guest on the spot--maybe later, however, when he stepped outside the pa.

Seeing nothing was preventing them and success was at hand, Grey then beckoned to Karaitiana, who came slowly toward the bed. He stopped, and

peered down at the chief lying in the bed, who then lifted his eyes to see who was

standing beside the white friend of his people. A little startled and amazed, the two aged chiefs recognized each other, and gazed upon each other for quite some time without speak, since it was the first time in many years.

What Karaitiana saw brought tears to his eyes. He exchanged a word of greeting with Te Hapuku who lay on a mat on the floor, with only a thin blanket of flax over his naked body.

Karaitiana saw the once glorious warrior and chief was now skin and bones, barely alive. Yet the spirit of Te Hapuku gleamed in his eyes, and it was fierce and warm, courageous and fearless! What Karaitiana loved in Te Hapuku was very much alive, despite the body’s decay and weakness due to age and disease.

Karaitiana knelt at the side of the dying champion of the Maori, the chief who did not give up until all others had surrendered their fighting spears. Speechless due to deep emotion, he waited for a word from Te Hapuku.

“Oh friend, how did you come here?” exclaimed Te Hapuku to Sir George.

Sir George answered: “I come upon the wings of love and have brought with me Karaitiana so that you may be friends once more before you leave this world.”

When Sir George said this, Te Hapuku put out his hand and he and Karaitiana clasped hands and wept.

All the weeping people in the pa were astonished at the sight. They stopped mourning and rejoiced instead. Never had they seen or heard of such a reconciliation between men who had been bitter enemies for such a long time, brought about at the very edge of death! It was a great, a very great miracle.

The white chief now was compared, in the words of the people, to the grey dove, a beautiful bird that brought good fortune wherever it alighted. Karaitiana spoke to his beloved friend, Te Hapuku, who now had forgiven him, how the white chief had grieved in his heart for them and had brought them together in the pa of Te Hapuku so that their hearts might be knit again into one heart.

Every honor that Te Hapuku’s people could give Sir George Grey was given. It was completely forgotten that he was a paheka. He was shown the sacred carvings in wood in the meeting house that held the powerful mana of the Maori. Their spiritual meanings had never been revealed to any white man before, but to the “Grey Dove” they freely opened the treasures of their hearts. “What does this carving mean?” the Grey Dove asked the people. “And this--?”

Sir George Grey was, thus, astonished to find that the Maori not only had recorded the Great Flood that had engulfed the whole earth along with the dividing up of the mother island into many islands large and small, but they had sailed on to the very end of of the archipelago of time, to the Thousand Year Reign of a holy “Son of God” they called the “Chief of chiefs.” Here the English Premier of New Zealand, for that is what the English had named the Island Kingdom of the Long Cloud, learned too of the rise of New Zealand and the larger island-continent of Australia to eminence during the thousand years’ reign. He also was shown the carvings signifying the “Bridge of the Giant Warriors” that connected the two Earths. All this prophetic vision of the past and the far future astonished Sir George. He asked and received permission from Te Hapuku to make wax rubbings of the most important carvings, leaving out only the carvings of the Two Earths, for he did not understand them and thought they were mere fancy.

“I know this Chief of chiefs that is mentioned in your mana!” he informed both chiefs on his return to the pa, and they were totally amazed, thinking the chief would not come, according to the carvings, not for a long time yet.

“Yes, that is true, he may not return for some time yet, but he has come!” He then explained how Jesus was born in a village named House of Bread in a far away land of green mountains and fertile valleys in the north and desert sands in the south, and how he died for all men’s sins, that they would be forgiven by his Father in heaven, the Father of all who made everything in earth and in the heavens. When he had finished explaining the story of Jesus as best he could (using the Jewish name, Y'shua, since it fitted the Maori tongue better than the harsh "j" of English), for he was a government official who had only some Church of England Sunday School training to fall back upon, and was not at all to be compared with a minister of the Gospel, he had completely convinced himself for the first time of the absolute truth of the Gospel in the mere telling of it to these two utterly awed, aged tribal chiefs, Te Hapuku and Karaitiana.

Both leaders, with all the men, women and children listening in, were reduced to tears by the account, demonstrating that for all their experience and warcraft they remained children, in that they were honest and unpretentious and simple at heart.

They mourned that their sins had served to kill such an innocent man as Jesus, who had come only to spare them the penalty of eternal punishment for their evil doing. Never had Sir George witnessed such sincere, total, and unabashed repentance—he was so affected that his own heart broke with theirs, and he willingly acknowledged his own sinful state.

What a scene for his eyes this was! The most fierce-looking savages, with body tattoos made with bone chisels and soot covering every inch of their bodies and face, they wept like babies when they heard about Jesus the Lamb of God.

This description of Y'shua the Mana from heaven proved to be the golden key to the hearts of the Maori. Though the white man had first brought sheep to the Land of the Long Cloud, the highly adaptable and intelligent Maori had soon learned the great value of sheep and the many uses of their wool and meat.

They also were acquainted with the sheep’s defenseless condition, along with its extreme meekness. To their warrior culture, where man-to-man fighting and contests of strength were so highly prized, that the Almighty God had chosen to make his Only Son like a sheep was the most disarming, affecting part of the Gospel Story.

They could not find it in themselves to resist God’s wondrous Lamb-Son—so had proven himself faithful to His Father’s plan for wicked men, overcoming every test of his strength that could be imagined.

The story transformed everyone in the pa after Sir George finished.

After a week’s stay in the kainga, the visitors departed, and on their way from Te Aute, a courier came on horseback, announcing that the Great Chief, Te Hapuku, had passed to the “kainga and pa of the Chief of chiefs.”

He passed quietly, the people said, in great happiness and peace, with his most treasured bracelets, given him by Karaitiana years before their estrangement, which he had them wrap around his arms before he would yield up his spirit.

Twelve months later Karaitiana lay down on his own death mat, and he announced he too was going to the kainga and pa of the Chief of chiefs.

Copyright (c) 2006, Butterfly Productions, All Rights ReservedM