OF

THE

CHRISTMAS

TRUCE,

VOLUME IV,

ANNO STELLAE

1914

Waste of Youth's most precious years,

Waste of ways the Saints have trod,

Waste of glory, waste of God.

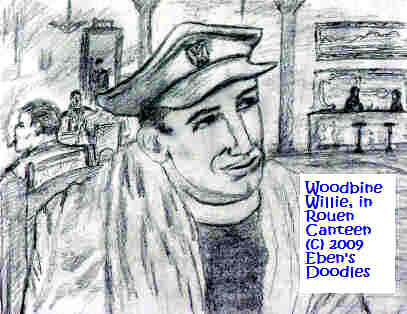

--Woodbine Willie, Chaplain, British Fourth Army

This war was, indeed, great in scope and consequence. It would topple the crowned heads of the monarchies of most of the European powers. As prophesied by a bearded, robed, iconic staretz in the Kremlin, this war broke out that would exhaust Europe, killing off nearly a whole generation in all the countries that fought it, then resume again some years later to devastate the entire continent with tens of millions more slain, both military and civilians.

June 28, 1914, two years after the Titanic converged with what was thought to be an iceberg and sank in the frigid Northern Atlantic waters off the island of Newfoundland, the aging but still vigorous heir to the imperial Austrian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand with his wife Sophie, paid a state visit to the South Slavs. What was so special about this? State visits by the Archduke were a matter of routine, for he was a world traveller. Where hadn't he visited? So a visit to the Balkans was not special, except that it went wrong, terribly wrong.

An expert huntsman (insofar as it required expertise to shoot game that was driven toward him by teams of men encircling the animals), whose palace walls back in Vienna were covered top to bottom with upwards of 200,000 antlers and mounted heads of every kind of game animal, the Archduke was in turn hunted and his carriage bombed by Serbian nationalists in Croatia.

Shock waves struck the hearts of the many peoples of Europe after the news flew rapidly by telegraph to every capital. Ultimatums were issued from Vienna to Serbia, and when they were not met by the recalcitrant Serbs, war was declared on Serbia by the Austro-Hungarian Empire, with Imperial Germany following suit as an ally.

The banners of all the newspapers blazed with war declarations of country after country. Orders went out to the male citizenry of France, Britain, Germany, and Austria, and other countries--mass mobilizations were begun. Millions of fighting quality age kissed their wives and children and left their homes and jobs and trekked to the army centers and depots for induction, training, outfitting, and weaponry.

Armies already in the field were rushed by train and on foot to positions along the borders between France and Germany. Factories were rapidly converted to supplying the many war machines. All available resources were committed to the war effort. Propaganda offices worked overtime, churning out war posters that portrayed the respective antagonists in the worst possible light. Spies fanned out by the thousands across Europe, slipping discreet bribes to officials in sensitive positions in war departments, using pretty women to lure army officers to divulge information, infiltrating wherever they could into the enemy countries to spot weaknesses or major movements of troops and material.

Army battalions paraded in the streets of a thousand cities, as men marched off to the Front with bands blaring and crowds madly waving handkerchiefs and flags and cheering them along.

All Europe (except neutralist Switzerland, Sweden, and a few other small countries who had nothing to gain from fighting with lions) was caught up in a frenzy of high expectation, terror, anxiety, anger, and vengence. This time the anciently seething wrongs which Europe never could forgive and forget would be righted, the enemy would be crushed and rendered powerless forever. Yet Europe was thought to be so civilized and enlightened by science and the Age of Reason, this time it would be different: unlike in the past, vengeance would not ignite another cycle of strife and warfare like in the past. Modern 20th Century Civilization with its enlightenment of the mind and spirit and nature of man would surely prevail over savagery, the primitive brute creature of base instincts that lingered as a vestigial legacy of ancestral Neanderthals in man's pedigree. Refined by education and the arts, modern man stood poised like an Olympic athlete in white running togs on the cusp of a new era of mankind's upward progress and development, entering a brave new world where there would never be need of war again, for victory would kiss the dove of peace and never let it fly away. A thousand years of peace would prevail over the entire earth, and science and industry would transform it into a paradise where the parliament of man, spoken of by Alfred Tennyson, would sit and levy only just decrees that would treat everyone equally.

This was, from the onset, to be the war to end all war: most everyone (except the grim, dark eyed staretz in the Kremlin) bought this wonderful, shining idea, and it added a burning fervor to the war not seen in all the prior conflicts on the Continent since the Thirty Years War and other wars of religion in the 1700s. The sirens of war, looking either their most seductive or just like the girl next door cried out to an entire generation of young men: "Fight this war, my darling, and win everlasting peace and happiness for yourself and your nation! Do your duty by the Fatherland and the blood of your forefathers! Defend the sacred hearth of the Home and your mother and sister's virtue against the raping barbarian! Crush our enemies, strike him down to the dust once and for all, trample him, etc., and your nation will heap on you imperishable honor and gratitude!"

Flags, flags, flags! Bands! Martial music and marching musicians with little boys tramping alongside with wooden rifles and stick bayonets! Speeches by government leaders before tens of thousands in public squares and grand boulevards. Parades. Cheering masses. Madness...as the dogs of Europe barked and howled from Edinburgh to Moscow.

There had been countless continental wars before, sometimes of great magnitude, especially in the times of Napoleon, so people thought it would be much the same thing, as most wars were far less ambitious in scope and therefore not that serious. Surely, this Europe was so civilized that this time time peace would be instituted and maintained indefinitely. After some bloodletting in a battle or two, the peace envoys would confer at some palace or other in France or Britain or Holland, a deal would be struck, and life would revert to the old paths and people could go on with their regular pursuits as before. But a new player entered the geopolitics in 1914, unknown and uninvited by the Great Powers, which changed everything and opened the abyss itself as the whole world for the first time was involved in a single war so destructive it seemed about to destroy civilization itself.

Not stopping over at London Rev. Kennedy went directly to Portsmouth, staggering beneath loaded bags aboard ship to Calais. The crossing was routine enough, with no Zeppelins dropping bombs on them this time, but the choppy water and the rolling old trawler turned transport made him run for the rail a number of times. Then Calais was a mad house. Every kind of transport was taken by military troops or hordes of fleeing citizenry from the provinces affected by the war. Showing his papers, the Customs waved him and his bags through without inspection. But where was he to stay, and how was he to get to the Front? He must have asked a hundred different people before he found a way out of Calais.

After paying an exorbitant amount as a bribe to the station master, he wedged himself and his bags into an officer's berth in a troop transporting train and reached Rouen, stoutly declaring to Customs he was carrying Bibles and religious materials (which was not a blatant lie, since the bags did contain some Bibles and religious materials, and the cigarettes were for the troops' morale, not his own use or for profit, something he knew they would not have believed even if he had declared them). Once he was free of the French authorities, he broke out the first case of cigarettes at the British canteen and handed them to a corporal nearest him.

He was a smash hit from the start! The thin, poorly rolled, adulterated French cigarettes available in town were clearly inferior to the British smokes based on prime Egyptian tobaccos, and expensive and hard to get too--and here they were being given free Brit cigarettes by the pack! Easily the most popular chaplain with his boyish looks and his generous way with cigarettes, he was being called "Woodbine Willie," and often the reverse, and was talking to as many soldiers as he could before they departed to the Front, just to inject some hope and cheer into the men headed for the trenches. He could see the specter of fear, even stark terror shining in the eyes of the grinning young men--the older ones were resigned to a bullet in the vitals or, for the less lucky, an exploding Teutonic shell with their names on it, but not these smooth-cheeked youths, who looked like mere choir boys to the chaplain. For these he had come--he knew he could drive out that paralyzing fear with love of country and love of God, and everyone knew that the Huns imperilled not only all Christian civilization but their homes and families. He would remind these boys they were here in France defending their beloved British mothers, daughters, and sisters back home, whom the Huns would surely rape if they could break through the Western Front and invade the homeland. The tow-haired Huns and Teutons of Kaiser Wilhelm had already ravished Belgium and to Poland and Russia; they had to be stopped in France, or they would overwhelm the whole West with rapine and barbarism!

He might have stayed in the relative comfort of the ancient, civilized city of old Normandy renowed for its ties to Joan of Arc, the teenaged maiden savior of France, and let the troops come to him. Other clerics might have done that, rather than muddy their shoes and clerical robes in the muck of war. But after waving away a hundred or so of his countrymen, Woodbine Willie felt he was not doing all he could any more. He couldn't just sit in safety and comfort, a nice pension around the corner to park his gear and bathe and sleep, while the troops were off facing and battling the Kaiser's hordes, slogging through mud, mud, and more mud. No, he had to do more! He needed to go with them and experience what they were going through, he decided. He expressed this desire of his heart to a soldier at his table, in fact, since he had nothing to hide in coming to minister faith and hope to Britain's grand warriors.

Then he smiled his most winning way whenever he was dealing with a man of the cloth--since he hadn't always found them men of practical reason, such as military men had to be if they weren't absolute bloody incompetents and flunkeys.

"Are you saying, sir, you'd order me to stop here?"

"No, I am not saying that!" the colonel blustered. "You have your commission and orders drawn up at the War Office, I presume, and no doubt they don't stipulate your precise location of duty--which is generally left at your own discretion in these cases--but, as one gentleman to another, I have seen these wars often enough, and I am just trying to give you a more sensible plan of action, one that will preserve your life for the sake of the troops who need a little cheer-up!"

Woodbine Willie smiled. "Your sentiment is appreciated, but the Lord will preserve me, not the governors of this war. He alone is my refuge, my fortress, my high tower. I'm not afraid of what mere flesh and blood or bombs can do to me. When can I go forward to stand alongside our brave lads? I can have my bags and my gear ready in five minutes, sir, but please afford me ten at least, so I can settle up properly with Madame Leblanc, the proprietress and concierge at my pension. I don't want the French to think we British take advantage of our allies and hosts!"

Motorized columns along with horse-drawn lorries converted from street cabs and wagons were already rolling out from Rouen, carrying cheering, laughing, celebrating troops to the Front on the Somme, where a major offensive by the Germans was just then being launched. They could even hear the distant thunder of the Big Berthas, the Germans' most powerful, long range artillery.

The colonel shook his head over the vivacity and spirit of this young chaplain, which had communicated visibly to most of the army personnel in the crowded room, then send an aide to find a place for him in his own staff car--a new American vehicle shipped over for the British ally.

The Brits had the stuff to whip the Hun back into his forest dens! Why not do it now, in the next week or so at the latest?

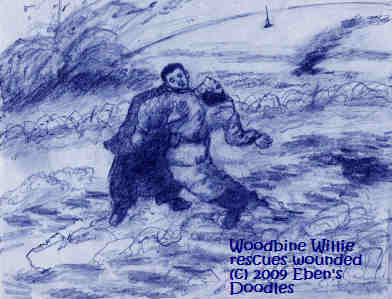

He was so enthusiastic, he went immediately to work and met with hundreds of men of the British Fourth Army in the dugouts and trenches, moving swiftly from position to position, greeting them, cheering them, handing out more Woodbines as fast as the hands reached for them. He was so glad he had come! He never felt more called by God than in doing this work. In fact, he felt more alive at the Front than anywhere else in his entire life. It was so exhilarating and glorious, rubbing shoulder to shoulder with the brave young men right where they were laying their lives on the line in defense of the Royal Crown and Christian Civilization, Hearth and Home.

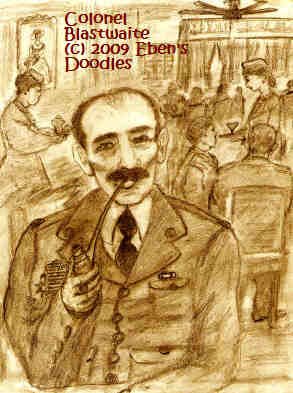

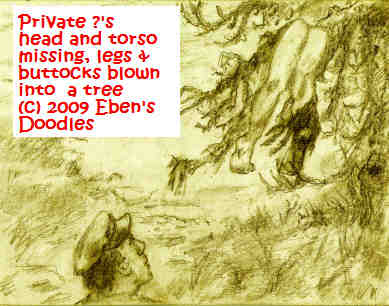

As he was moving toward another sand-bagged trench system nearest the German lines, incoming shells from Big Berthas reached the forward position before he could. He found himself wandering about dazedly in the next minutes, his ears ringing, as the ground eventually settled back, the air cleared, and he could see again where he was. But everything was changed, so utterly the terrain looked nothing like what it had been just a short time before. He had been walking through some wizened apple trees of an old orchard that still had apples clinging to unpicked branches, and now the orchard was gone, except for one shattered tree behind him. The farmhouse, requisitioned for the HQ of the frontline commander, Lt. Col. Blastwaite, was also blown away--not a trace remaining! Everywhere, the earth lay in smoking heaps, with water filled craters between. He made his way slowly through the torn up earth and tree roots, trying to find his way back to where he had been, but then heard moaning and wheezing sounds. He went to investigate, and found a soldier lying on his back on the inner lip of a bomb crater. He was moving his arms in a feeble sort of way, flopping them about limp-wristedly, and appeared barely conscious or alive.

Kneeling down by him, he found the soldier was missing his legs from the thigh down. He was ashen colored in his face, and it was certain to Woodbine Willie the young man had only a few more moments of life, if that.

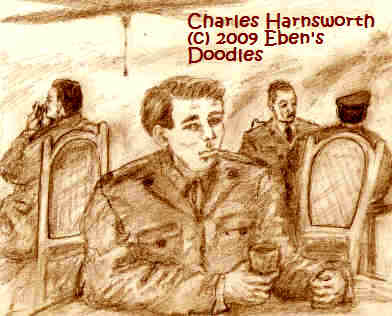

"What is your name, son?" he stammered, as he pressed a cross against his forehead. The young man blinked and answered, and Woodbine Willie recognized him by his voice. Charles Harnsworth, from Tewksbury. He grew up just a few steps from the old Norman cathedral and used to play marbles with his chums on its steps and even in the vestibule until the vicar caught wind of it and chased them off! He had met this very fellow at the canteen in Rouen, and had a jolly conversation boosting his spirits, as unlike his buddies around him he had seemed particularly down at the time, confessing to him that he greatly feared imminent death--what with his fiance waiting for him back home and all.

All he could do was clamp his hands over his head and ears as the horrific explosions took place. Sometimes big clods of mud and earth dumped down on him. One time the shell came so close when it exploded that he felt the earth rise up under his feet, and he was pitched forward. When he realized he was alive and intact, he found he had fallen face into the mud, most of which was a blown-up manure pile.

He had no time to answer, as he was surrounded by dark forms, which spoke British and had to be his countrymen. He called out for help, and was then dragged from the muck and hauled to his feet.

He stood trying to tell his rescuers what had happened, but nothing coherent came out. He said some strange things--about poor bloody Charles, the Norman cathedral, the marbles game, and quite left out that he was a vicar, a commissioned chaplain at the Front, and had got lost in no-man's land after finding poor Charles in such a bad way, virtually legsless.

What did a legless man matter? Hundreds of such happened every hour on the Front. Having seen many a man go daft like this before in the trenches, the sergeant ordered his men to take the noncombatant back to the HQ that had just been set up to replace the one the late Colonel Blastwaite had so briefly occupied. A fire had been started in the ancient ceramic-tiled stove of the farmhouse, a water pot rummaged out of the litter on the floor, some water strained through a cloth from a big puddle where a dead cat lay floating with a doll's head, enough to put on for tea, and a group with some cards was having a little amusement while they waited for a replacement for Blastwaite to show up--probably a rosy-cheeked lieutenant, with too much spit and polish this time, fresh out of officer's school, they figured, as colonels weren't considered as expendable as privates and corporals so no more would be hazarded at that luckless post.

"Well, bust my ballocks," one player remarked about his former commander. "You oughta seen what was left of the old colonel. Nothing! Not even a vertebra or tooth or finger! Blown to bloody atoms, he was! A fair decent bloke for an officer, he was! Let me share his private reserve of a fancy sherry, chilled in a bucket of ice he brought along from his hotel--which was jolly fine of him. Talked straight to me as though I were a colonel too! Shame it had to be him, but better than it be me, mates!" He laughed, and the others joined.

Stripped of his coat, scarf, and clerical shirt and collar, which had been strung over the stove on a length of barbed wire on two poles, Woodbine Willie sat miserably crouched in his skivvies on a crate, trying to get warm as the fire gained on the wood scraps and tree limbs stuffed into the stove.

"Reverend, you must return to Rouen! This is no place for the likes of you. It's not safe here. You're a gentleman, a man of the Cloth. You haven't been trained for it, what you see here. It has shook your mind a bit off the rails, that's all it is, but a day or two in Rouen will bring you back, and you'll be fine again, your old self, sir. Now come with me, and I'll get some bloke who'll take you right back to your hotel, and then go and treat yourself a nice, hot milk with whiskey and go straight to bed! That will fix you bloody right. We'll send you right back in the motorcar that fetches our new commander. I'm sure that will be fine with him--as he won't be going anywhere soon, not when the Huns reset the coordinates and crank those Big Berthas in our direction again after finishing off the Frenchies further to the east and west of us! You just sit and watch your clothes dry, and I'll speak to the bloody lieutenant when he comes. It shouldn't be long now, as we sent word about Blastwaite in four hours ago. They said they'd send someone immediately! Of course, they had to finish their cigars and brandy first!"

Woodbine Willie cradled his head in his arms. How it ached! His whole body ached. But it wasn't from any injury, it was just from the crashing realization of what war really signified, which he couldn't possibly put into words. Despite the vision in the mud, his every cell and atom screamed speechlessly, "NO, NO, NO, NO!"

God, vision or no vision, couldn't get off so easily with a vision, if that was what it was, he thought. It was still No! to war, to the blowing up of all the bright-eyed, apple-cheeked Charley Harnsworths, and for nothing really! What good did it do to snuff out Harnsworth and tens of thousands of lads like him? Nobody even knew it back at HQ where Harnsworth was or what had happened to him. He had tried to tell the men, but they just laughed and joked.

"Well, well, isn't that so!" they humored him. "We'll not expect him then at reverie, will we chums? Hahaha!"

"And dip me out at mess one more cup of rotten whore's ----, righto?" quipped another, slapping his knee with a card.

Even the chaplain, unused to such filthy talk in clerical circles, recognized the term, the dirtiest he had ever heard as a boy from bad street boys.

Clothes or no clothes, Woodbine Willie wanted to rush out into the night. How could these men be so savage as to joke ghoulishly about the deaths of their countrymen like that, brave men who had given their very lives for the Empire and its cause? War had turned them into brute barbarians! That had to be the reason. Surely, if he could only get back to civilization and the ancient civil code of honor among gentlemen, he would report them, and they would be hauled out and soundly disciplined as they should be.

But who would listen to him, if he ran out of there practically naked? They might think he had lost all his wits and clap him in the infirmary back at base camp. No, he realized he had to wait, and let his things dry out first, then try to make himself more presentable in the present appalling conditions.

The kindly serjeant brought him a cup he had found among the crockery in the cupboards he had filled from a bottle after blowing out the dust and mouse droppings in the cup.

Woodbine Willie looked up at the serjeant.

"Just a little kiss from the vine to strengthen your spirits, Reverend," the sergeant smiled. "Try it! It'll warm and settle your vitals. You will feel better soon."

Woodbine Willie took a sip, and realized somehow the serjeant had found a vintage year wine, maybe taken from a hidden cellar he had found and broken into. Centuries old French farmsteads that looked like nothing but squalid, medieval peasants' hovels on the outside were renowned for gold socked away in foundations and hidden cellars stuffed with first-class cheeses, wines, sausages--which the owners left when they fled the area under attack, intending to return later to empty them out once the armies quit fighting and moved on. But sometimes the farmers were long delayed, as they couldn't get passes through the lines, and so the stocked cellars--if they could be found--fell to whomever was fortunate to find them first.

Slicing the excellent, smoked sausage, the friendly serjeant passed some on his big Swiss knife to the chaplain, along with a wedge of cheese. "Help yourself, sir, it may be some time before you get to a commissary and have a proper meal. It'll keep the life in you until then, that is."

Woodbine took the cheese and sausage, washed it down with the wonderful wine, and he did feel better after a few minutes--though not so merry he wanted to laugh at corpses of dead boys.

Gratefully, he felt a degree of warmth and ease circulate in his body and the terrible drumbeat of war withdrew from his shattered nerves, enough so that he nearly dozed off sitting, a pad in his hand where he had scribbled something that turned out to be his first war poem....

The new commanding officer strode in, halted abruptly and stood there watching as the card players quickly kicked back from the table and stood to attention.

But not quick enough for the new chief! "Serjeant!" the lieutenant barked. "What is the meaning of this lack of military bearing? Why aren't you and your men outside at your assigned duties? Just what is going on here? I caught you all cosy as kittens in a darning basket, playing cards! This is a war going on...a real war! Are you here to play or do your duty, fight and give your lives for the King and the Empire? I will have you all demoted for this, if you don't mend your ways at once! Now move! Get out! And be smart at it!"

"Serjeant! What in the world is wrong with that soldier there? Where is his uniform? He's practically...indecent! Serjeant, get him a uniform at once! This post is a disgrace, men out of uniform, running about in their skivvies!"

The serjeant moved quickly, saluting, then explaining, "The Chaplain, sir! He had a little accident out in the wet--got his clothes a little muddy. So we've been dryin' them off for him, sir!"

Lt. Crasswell exploded. "This is MY assigned headquarters! I won't have it looking like a Chinese laundry! Pull that line down at once! Sweep this floor and tidy the place! I want this place cleaned and put to order immediately. And get that fellow attired properly! I have no use for chaplains here--send him on his way. We have a war to fight, not a ladies' tea social!"

Embarrassed and also angered, Woodbine Willie hastily pulled on his clothes with the serjeant's help, and even if they were a bit damp, they were warm enough and at least could be worn.

Meanwhile, the men had cleared the table, set it with a single chair, and the lieutenant was now seated, with his papers spread out as if he were conducting a major campaign.

Lt. Crasswell turned to the serjeant. "Well, get moving! Pack him off to Rouen at once! I don't want him here a moment longer, whoever he is. Time is of the essence if we're to beat the bloody Huns and burn that wolves' den of Berlin to the ground! I've got a lot of work to do!"

"But sir, it requires a decent, motored transport to move him! He's been shaken up and can't walk in his condition! He has no horse either. We must furnish motor transport, sir, he'll not stay on a horse's back in his condition!"

"Well, then, use my staff car if you must! Just get him out of my sight, so I can install some proper order here!"

Woodbine Willie was in no mood to argue with the shouting, conceited lieutenant. He was escorted out of the farmhouse by the searjeant and to the car, who tipped his hat and spoke privately to the chaplain.

"My apologies, Reverend, for this newcomer. He is fresh at this game, and, just between you and me, sir, he don't know which end he shits from. Why, my old chums back serving at the main command post--you know, where all the colonels and the generals hobnob and dance with the high-class Parisian broads at the club and drink too much-- sent word to me on the sly the Fourth Army has been murthered. Murthered! Now what's left of us will soon be pulled back to somewhere south. We're waiting for the order to come down any time now, so why fight?--we've been beat so bad there isn't a Fourth Army, so what's the use of sticking our necks out to get them shot off now? Will you be leaving the Front any time soon? I'd advise it, sir. It's nothing but a meatgrinder here--and we're the bloody sausages!"

"

"That's all right, Serjeant," Woodbine Willie said, his thoughts whirling in his head like big chunks of wood rafters in swirling dark waters. "Please allow me a little time to think about it before I decide what to do next." The serjeant nodded, saluted, then shut the door, and the car moved off down the farmstead road.

"I'm Terrence Blassinggame Codd, at your service, sir, but you can call me just T.B. or Coddie if you like. And you're the famed army chaplain, Woodbine Willie, I presume?"

"Oh, so what if I am!"

"Well, I remember seeing you back at the Canteen, and you tipped me two whole packs of Woodbines and we talked for the longest time! Jolly nice of you, Reverend! We all think you are a great fellow, for being so generous and a real chum to us."

Woodbine Willie did not reply. Oddly, he didn't remember Codd, and he knew he never forgot a face. But the corporal rattled on, sharing all his thoughts the moment they flitted through his skull.

"You may think this is rather queer, sir, how this here is a staff car without officer's flags and insignia. But the Germans got wind of our new motorized transports and sent snipers wearing the uniforms of captured the uniforms of captured Brits and crossed the lines, and they were picking off the officers in their fine new cars, one after the other. It was a wondrous turkey shoot! So I've removed the flags on the hood, and Crasswell approved, but only after he heard how many shots we took and various officers shot right in the forehead! He practically hugged the floorboards as I drove to the post though. And this is that fancy American car shipped over, so I have to sit on the left and steer--imagine that, a steer wheel on the left, right next to the uncoming traffic--what sense is that? I'd be the first to be hit!

"Uh, I wonder if we'll find the main track. This country is all new to me, and after the Big Berthas are through for the day, it looks completely different from the day before! I don't like it one bit! It's so beastly. These bloody allies the Frenchies are quite a different kettle of fish, aren't they? I am German from Bremen on my mother's side, and never did like the French overly much, but that's the breaks, we have to fight and do our duty by His Royal Majesty and save our allies from getting whipped all the way back to Paris--for we all know what poor fighters these little chaps are, not like us red-blooded Brits, who can turn back a whole battalion with only a single Lee-Enfield passed between us!"

The corporal laughed as he searched the terrain for the main road. The road appeared, not as a metalled road but a mass of snow and mud churned up by countless feet, horses' hooves and wheels of heavy transports drawing tons of artillery and explosives, and even the tracks of the new experimental tank that was being tried out at the Front.

It was a very bumpy ride for the chaplain, as he was thrown up and down and side to side as they lurched toward Rouen to the south.

They met masses of infantry slogging forward through the muck and snow, their heads down. Occasionally, a few looked up as they were stopping to relieve themselves without bothering to turn aside from view, somehow recognized Woodbine Willie in the cab, and shouted and waved to him.

Woodbine Willie, after a couple times of this, sank down in his seat.

They got stuck several times, but Codd proved efficient at dealing with potholes, jumping out and grabbing a shovel from the back and with a sack under the wheel, he soon had it out, and they were on their way again. A couple times Woodbine Willie got out and pushed, and Codd thanked him, saying the lieutenant wouldn't have done something like to save his life. They had got stuck four times on the trip out, and the Crasswell and his aides just sat in the cab and wouldn't lift one finger to help him. They didn't want to muddy boots and gloves or catch a stray bullet in their marriage prospects!

Woodbine Willie liked Codd better after hearing this, and they rode on.

They met a mass of infantry, mostly on the road but also moving up on both sides. It seemed to have halted for some reason, as a car from HQ brought word.

Seeing the confusion and the delay it would cost them--for it would be hard to press through all those hundreds of men, wagons, and horses, and the occasional tank--Codd left the chaplain and went to inquire from any officer he could find.

He came back a few minutes later, and grinned at the chaplain. "Everyone is ordered back, to be repositioned south! That means that bloody little Crasswell too! But he can cool his fine heels a while, as I take you to town first and then take your leave and hit a few nightspots I know of--your're invited, sir, if you would like that sort of thing--but I presume you aren't my kind, righto?"

Codd winked, but Woodbine Willie was not responding, so Codd started whistling something jaunty he had learned in a London playhouse and left the chaplain to his somber thoughts.

The road was soon cleared enough as the men let their car through.

They made good time, despite some more potholes and shoveling out incidents. Civilization, Rouen, appeared, hazy and spired, on the horizon. Behind them, anarchy and chaos and barbarism without restraint, and the columns of what was left of the British Fourth Army straggled southward to take up a rearguard position, which was all they had troop numbers for.

Madame Leblanc stood, scrutinizing him as he hung to the door for support, fighting dizziness and the sight of the nightmarish dismemberment of Madame Leblanc and what might follow next with his own body parts, which reminded him so acutely of what he had just seen out in no-man's land.

Finally, she spoke in her quite tolerable English, a certain annoyed strain in her voice. "You do not wish the absinthe, Monsieur? I think not it is so good for you. Please get rest and not drink so much, oui? You are feeling ill? I could call the doctor who take care of my mother when she die. He would know how to help you. You really do not look your old self, Monsieur. Why you cause yourself and me this trouble, oui?"

The next conscious thing he was aware of was that he was looking up into the flaring nostrils of a huge whiskery gentleman.

The doctor turned to Madame Leblanc as he was moving toward the door. She brought his hat, cane, and cloak. As he got ready to go out, he turned back to his patient. "I counseled you like father, not only a doctor. Take my counsel! It is for your own good. Do not punish yourself so, for you are young, things will change. They always change. Some good, some bad ways, but they always change. I do not know why you were doing this to your body, but I can tell you--whatever it is, your wife, your lover maybe, run off with another man, a business collapse, some other great disappointment in your life--it is not worth destroying your young life. Live! Live! You are a young man yet! You see things will change, if only you will carry on. Now adieu!

The doctor tipped his tall, beaverskin hat with a great old-fashioned flourish to the landlady, told her there would be no charge, and she showed him out, bowing her head as he stepped with dignity out of the room.

Madame Leblanc stood at the doorway and gazed back at chaplains.

"What will you do now, Monsieur? What will you decide? I was most concerned for you these last days. Please give heed to the good doctor. He is a fine gentleman, oui? A bit too old for me, of course, but still attractive to a woman in how he treats my poor, little, weaker sex, oui?"

Woodbine Willie stared at her with bleary eyes, and then laid his head back on the pillow of the bed where someone had carried him. He closed his eyes, and Madame Leblanc sighed after her failure to draw him out sympathetically, then quietly closed the door.

The air of the outdoors struck his burning face like a slap of cold salt water in the face. But he continued walking down the street, dodging the wheeled traffic and dogs and people and bicycles. When he had got to a wooded park, he turned in through the high iron gate, paying the woman in charge to take the gravel paths that would lead him to more solitude at that moment when he felt he needed it most. Just to get away from prying eyes, that was what he wanted. He came to a bench and swept the snow from it and sat to rest himself. He leaned his head back, despite the icy coldness of the iron frame. It felt good and eased his over-heated brain. His thoughts wandered. But then always came back to the question: what now? If no God, what now? What would he do? What meaning was there to life now? He felt cast utterly adrift in a black, trackless waste of ocean.

Then he thought about Charles Harnsworth. He had tried to help him, give him some comfort in his last moments. Had he succeeded? At least he had not died alone, abandoned by everyone out there. That is one thing he knew. Where there others like him? Surely! They could not be counted! Men on both sides of the conflict, no doubt, missed but not searched for, and so they perished alone in absolute wretchedness. What about them?

It slowly dawned on him as he sat lingering in the late afternoon of the dying day in old Rouen's park that he could do something--something was needed that he could do if he chose. He owed it as his duty to his fellow man, he felt, to try and comfort the dying on the fields of war, no matter who they were,l or what they believed. Could he do that?

He sat up, his head a bit dizzy, but now more conscious of a gleam in the darkness that had engulfed and smothered him for days. The drink had not helped in the ease, only put off the final decision: to live or take his life. But now he had a reason to live possibly: aiding the suffering and dying boys on the war front. Yes, there was the Red Cross, but they could not be everywhere, and so thousands still perished alone, uncared for. As a chaplain, he could go places they could not. He had more freedom of movement, being a single person, and could reach forward positions and even no-man's land where the Red Cross was not permitted.

He rose to his feet. He now saw the gleam become a shining, beckoning light, illuminating the gravel path before him. He began walking on it, and it led him back out of the park and back to his pension. He nodded to Madame Leblanc and then went up to his room. As he was getting his things together for another trip into the war zone, he called Madame Leblanc to send up a medicinal tea, if she had such. She brought peppermint, and he was able to take a few sips. Then he went to bed and rested the night through, sleeping soundly. In the morning he rose early, ate half a croissant and washed it down with some more tea, then went out, and his legs felt stronger now as he continued toward the canteen. There he knew he would find the officers who commanded at the front, as they passed through on their way. He would also find the boys who needed his help, not at the canteen but perhaps later out in no-man's land where millions were still being slaughtered week after week. While at the Canteen, he could also take names and addresses of families the boys wanted him to contact if anything happened to them.

He sighed. It would take far better weapons than those these humans presently employed to do the job thoroughly-- exterminate every last breeding couple and render the human race extinct.

But would Atlantis ever be rebuilt without resort to this slave pool? It had been handy before, but now it was completely out of control, and like a disease no cure seemed to be feasible, not for a long time anyway.

He turned away from the viewport, and walked back to his quarters. He had papers to finish on the question and possible strategies to use for handling affairs in such a way that they might resume total governance and control. Many others had attempted a final solution, of course, before him, but the problem remained and had to be dealt with, like it or not.

Just then a blinding revelation struck him. Why hadn't anyone else seen it before him? he wondered. It was so marvelously simple! It was so marvelous neat and clean, this Final Solution! He knew without the least doubt he had the answer to the Gordian Knot! He knew just how to slice it and solve the conumdrum of human existence that had spoiled the Atlantean hegemony for ages!

His heart, if he had one, raced with excitement, and he hurried off.

The prince never reached his stateroom, unfortunately, so he could set his master plan down on paper.

An assassin, sent from a claimant to the Throne to take liquidate all possible rivals, eluded his cordon of bodyguards and reached him.

Strangely, human bodies too could hold souls every bit as pitiless as these Atlanteans, and hundreds, even thousands of classic Atlantean-types pored over charts and maps daily in war rooms scattered across the European Continent as they plotted the maneuvers of vast armies on both sides of the Western and Eastern Fronts.

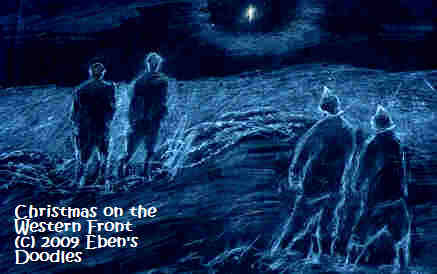

In the darkness, death, and despair that hung over the greatest wound men could inflict on themselves and the planet, where whole nations were bleeding to death, a single greater light began to shine. Already millions of British and French, nearly a whole generation of young men in each nation, were slain, and millions more drawn from old age and boyhood years faced the same fate in the coming weeks, but shone like a star, and it was a star, the miraculous Nativity Star of Christmas Eve. Only that star could drive back the Red Star and penetrate the turbulent, fear-haunted morasses of mile upon mile of trenches, bunkers and fortresses and no-man's land with its light and reach the hearts of the combatants, German, British, French, and Austrian.

Nothing like it had ever happened before, for soon German troops at their side of the Front began singing Christmas carols, and the Brits and French across the shell-cratered, barbwired strip of no-man's land that separated the two armies responded with Christmas carols, joining the Germans in the celebration. The guns stopped firing. Men began to get up out of the trenches, and the bravest, still singing, began to move forward, without their guns. Slowly, they approached each other, and then the miracle of this first Christmas Eve on the Western Front: men who were committed to killing each other clasped hands and smiled and laughed, wishing each other Merry Christmas in their respective languages. What was happening? What was this? It was the Christmas Truce of 1914.

All the trees for miles around had been blasted to bits, but the men, both British and Germans, gathered branches and stray bits, and wired together a "weihnachsbaum," a Christmas tree.

Hanging medals and brass buttons on it taken from their uniforms and those of dead troops, anything they could find that would add some beauty and gleam to the makeshift tree, the men gathered round it and sang "Silent Night," which was an international song that reached across all the divisions of war and politics.

Peace broke out all along the Front, as the soldiers poured out of the trenches, to join the ones gathered at the Christmas Tree.

Yet the Truce, while it lasted, was more than magical. It was unlike anything ever experienced on earth before, at least since the First Nativity in old Bethlehem of Judaea.

Surviving the war, Woodbine Willie laid aside his clerical collar and robe and campaigned tirelessly in meeting after meeting for disarmament and the abolition of war and all armies and weaponry. He believed that if no one was permitted to bear arms, and even speech in favor of fighting was banned, universal peace would result. He met many who disagreed, often Christians who pointed out the underlying sin problem with humanity, that envy, greed, and lust and fear caused ceaseless warfare and would always do so until Christ came again to reign over the whole earth. But he always had an answer to them: the Great War. Was good was it? What good did any war do? But who or what could have stopped it in its tracks? Well, he knew the only logical answer which the Christian religion had failed to supply: the world had not yet agreed to ban war and anything that might contribute to causing it, but if it would do so, a new world of compassion and love could be brought into existence. The old Christian God had utterly failed, he said, to solve the age-old conflicts; war bred war, in an endless cycle. Christ on the Cross had not stopped the machine gunning and the Krupp artillery. Christ was a dismal failure in his role of "Prince of Peace." But man could do what God could or would not do. He declared to cheering thousands in Liverpool (his last speech) that if a parliament of mankind were called, and the vote taken to put a ban into effect, with all the law enforcement agencies ordered to make it stick with severe penalties, peace would be achieved, lastingly, for the entire world.

To claim that Christianity and its "god" called Christ was a failed pursuit, Woodbine Willie made the necessary effort to forget the vision he had of the suffering Christ as he lay in the bomb crater. God was above and beyond all human suffering, he was God, was he not? He was in heaven, not on earth mucking about with common men? All that stuff about his being born in Bethlehem, made a mere baby, then growing up to share all the pain and temptation common to men so he could identify completely with the human condition before he went to the cross--well, that was sheer, fabricated nonsense, fairy tales spun after the fact of his execution to make something good out of something terrible, a human death. As for Christ showing himself to him as the Suffering Lamb of God, slain for the sin of mankind, so that they could be forgiven and restored and healed, he thought, or made himself think, it was only a figment of his imagination. The reality of war, the insanity of it, drove him to the end, and his end, a collapse at the lectern, came even as he was speaking for peace and the absolute necessity of a world parliament and a ban against war.

Groups calling for universal disarmanent, for vegetarianism, for Esperanza as the universal language, for the restoring of various Balkan monarchs deposed by plebisites and voting publics, for Anarchy and the end of all organized governments and law enforcement systems and agencies, for mandatory contraception and the reduction of the world's population to 50 millions, for the elimination of all national borders and free love, for Reformed Rosicrucian religion as the New World Religion unifying all the world's faiths, and, last but not least, the Flat Earth Society--the delegates and representatives of all these exotic and often competing groups rushed toward the lectern, and it became a mob that the bobbies found impossible to control and push back. When the body was at last freed for the medical men to get access to him, the gentleman was found badly trampled and no life left to revive.

But Woodbine Willie's career came to an end abruptly, with no more reason for his following it. "What a waste of a good-hearted man!" he thought. "And he was so sincere about what he was doing, so dedicated, so passionate. What could he have done if he had continued with Yeshua, not abandoned him?"

He had to leave with his question, as he felt a tug from out of the photo-cell that was irresistable. In seconds he was flying toward the portal, and then shot through into the vast spaces of the Vampire's eye.

The chief witness, Anne Foxe-Davies Fox, a lower-level Universal Disarmament and Peace Party delegate who had been at the scene taking notes and narrowly survived it, recalled in testimony to the court how the mob rushed at the speaker, the Reverend Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy, before she too was pushed to the floor and nearly trampled to death herself--ruining her almost-new, bargain store dress and hat costing 5 pounds. She had spent two weeks recovering in hospital with a collapsed lung.

She described the speaker's face and expressions shortly before he sank from sight, clutching his breast.

"Madame Fox, did the deceased say anything in your hearing, since you have testified you were standing quite close, a few feet away from the object of our inquiry?"

"Oh, yes, Your Grace, I did hear him utter these very words, Your Grace, these exact words, mind you, 'Keep away! Didn't I tell you? Keep away, you bloody lamb!" "Yes, that is all it was--'Keep away! Didn't I tell you? Keep away, you bloody lamb!' The presiding lord's perfectly white brows met beneath his perfectly white wig as he leaned forward and attempted to obtain a more precise meaning to this incredible ejaculation of the deceased.

"Now, Madame, what do you suppose he meant by them?"

"What do I suppose? Well, now, that is all he said, his last words, I mean, but I couldn't possibly venture as to what he meant by them. That would be giving my own opinion on it, wouldn't it?"

The witness was obviously frightened, and looked about herself in the witness stand, and seemed as if she might bolt right out of it without proper leave.

"Now, now," soothed the presiding judge from the House of Lords. "We are not forcing an opinion from you that you aren't willing to give voluntarily, Madame. But being so close to the said gentleman, perhaps you felt something or detected a certain element in his manner that could reasonably suggest to us a possible explanation for his strange utterance. That is all we are referring to. You needn't feel you must give us your impression, as it is completely at your own discretion, whether you wish to render it to the court or not."

Reassured thusly, the lady did indeed venture her opinion, seeing that it was all simple conjecture anyway, and wouldn't be held to her account, whether they agreed with it or not. After all, a lady was entitled to a touch of "woman's intuition," wasn't she?

"If it may help the honorable court any, yes, Your Grace, I did receive a certain distinct, but queer impression or tincture from the gentleman." She paused for dramatic emphasis, wiped her sniffle with a tiny, embroidered handkerchief, then resumed her testimony. "Your Grace, he was speaking as if directly to a real, flesh and blood personage standing right there before him, not down at some animal, or a lamb, so to speak. Believe it or not, I saw him do it! He was addressing someone at eye level, though without steps to support that invisible personage, being he would be situated BEFORE the lectern, standing on nothing but thin air, your Grace, not to the side of him on either left or right with him on the platform. And he was so horrified, so repulsed, I was quite appalled by his violent distaste and disdain. I thought, 'What on earth is so bad that this man is seeing or imagining, which I cannot see? What could be so ghastly to provoke him to such extreme emotion?' She waved a sodden handkerchief rhetorically.

"But there was no time to find out, Your Grace. He dropped like a stone almost immediately after his outcry, his hand gripping himself in the chest, with a pained expression most distressing to see, I can assure Your Grace. It was quite..., Your Grace, so very distressing! He was such a good-hearted little man--we all, the whole world peace community, admired him so greatly, and he was much loved for his great sacrifices for the causes of universal peace and a humanity freed at last from the shackles of religion and blind belief in the existence of God. That poor gentleman's violent death throes-- I get dreams and shudder so in my sleep about it sometimes even now, I do!"

The witness had quite worn out her handkerchief, it was plain to see, as she concluded her testimony, and no court tissues were to be had. The somewhat rattled witness was given leave to quit the stand, and she got down with assistance from two court bailiffs, the panel of judges shaking their wigged heads, and scratching at their notepads as they entered final notes. The judge banged the gavel, and the inquiry ended, with the upshot published later on in the following year in a distressingly dull, otiose government document of over 700 pages, entitled: "Findings of His Majesty's Court Hearing and Investigation Concerning Reputed Irregularities and Speculations in the Death of the Reverend Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy, D.D., Former Chaplain, British 4th Army, Battle of the Somme, Et cet., Under the Auspices of House of Lords..."

Meanwhile, Reverend Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy lay anonymously beneath his unmarked grave stone. His chief claim to fame was that he was popularly known as Woodbine Willie while he ministered on the Western Front among hundreds of thousands of British troops, but fame, like life itself, is fleeting, and now he lay at rest, at peace, beneath the rocky sods of his native land of the Scots.

It was as good and problematic place as any, for such as the Reverend who unfrocked himself. Why the skirling, skirted, bag-piping Gaels, trekking all the way from the hot, dry sands of Central Asia and eastern China and come to be called Picts and Scots and worse, ever claimed such inhospitable, damp, mist- draped, boggy and high rocky mountains and knee-knocking temperatures, remained unfathomable--unless they were pressed by superior hostile forces, the Imperial Romans being last among them, into the most inaccessible parts of the north and had no choice. But there they were free at least to seek refuge in caves and little thatch-roofed hollows dug below stone ledges or above ground dwellings fashioned of stones piled up to make conical bee-hive huts.

It was, from time immemorial and until then a cold land even in late spring, growing ever colder, and before long the permafrost set in, encasing poor Woodbine Willie of the exploded heart forever in the Big Chill, the Global cooking that rendered all his valid, haunting, agonizing questions and disappointingly lame conclusions, meaningless-- except perhaps the unfrocked Reverend's final words, "Keep away, you bloody Lamb!"-- that still retained some poignant Christian meaning and ought to have been engraved on his bare grave marker instead of the rather strained, hackneyed and prosaic platitude that some admiring pacifist passer-by volunteered with his knife point and chisel:

"War is bloody Hell, Heaven is bloody Peace.

Get rid of bloody God,

and find bloody Release!"

Woodbine Willie, still not deterred, continued his campaigns for an international ban on war. Forgetting the miracle and promise of the Christmas Truce of 1914 on the Western Front, Peace had become his god, and he himself became the cross on which his illusion of peace was nailed.

World War II broke out in 1939 with the Nazis' invasion of Poland. This was the lunacy of the Great War all over again, but with greater destructiveness, due to all the new weaponry and aircraft, missles and submarines, not to mention jet aircraft and a nuclear bomb.

Yet somehow this stunning failure of Woodbine Willie's, added to that of thousands like him, did not stop the peace movements (for nothing, not sense, nor logic, nor history, nor human experience through the ages could divert them) which held as their objective the universal banning of war. The movements survived their founders' deaths, and flourished right up to the time of Anti-Christ-ruled Earth's last war. Yeshua (Himself the Christmas Truce of Universal Peace) would return, setting his foot on the Mt. of Olives in Jerusalem, splitting it like a cocoanut, while slaying the world's armies that had come to assault his city and slay all the Jews.

Meanwhile, Ero was not in limbo, he was entering yet another photo-file. His presence sometimes turned things to good, but not always, as his experience in Woodbine Willie's case had shown. Once set on his course to nihilism and death, all in the cause of "world peace," doubt had kept him locked into his downward spiral into nothingness and oblivion. It couldn't be helped! A man's mind, once made up like Woodbine Willie's, could not be turned past a certain point back to the light.

This was to be expected, of course, as the Vampire fed on the despair and hopelessness of its victims. Where next? What could be worse than what he had just seen?-- the ruin of a once promising vicar with an enlarged, highly sensitive heart whose chief fault, if fault it was, that his compassion and capacity to suffer with the hurting were greater than his mind and spirit could bear?