They committed overwhelming navy and army forces to deal the colonies a quick and decisive blow. Most frustrating, however, was the weather. It had intervened on a number of occasions, upsetting the best-laid plans of the war ministers.

Except in the matter of the weather and other contingencies called acts of God, they held the advantage in men, material, and fighting experience, not to mention superiority in strategy, yet victory eluded them.

France was their primary foe, they knew that. Not the lucrative but militarily paltry American colonies! So what was to be done? What they must do they must do quickly. In the great gold and art-incrusted halls and chambers of Buckingham House, the king-—whose choler was never very stable at best--was growing increasingly restless and agitated as the skirmish over in America lengthened, with yet no clear end in sight.

The royal will finally came down to a certain lieutenant in the army, an expert sharpshooter who was renowned for his sure and deadly aim.

Called to the major’s office and let in by a servant, Lt. William Ferguson saluted the officer seated at the desk, a man and his commanding officer he had not even known existed until a hour before the interview.

Then he himself stood as the lieutenant sat down in a comfortable chair.

“A thousand pounds, by accurate count I made myself,” Major Mudgett began. “Go ahead and count it yourself, if you wish.”

He watched with some amusement as Lt. Ferguson took the opportunity to count the purse’s contents.

Then the lieutenant lifted eyes to the major’s in clear inquiry.

“It’s just a little encouragement from the war ministry to you, in the pursuance of your duty.”

“My duty, sir? It can’t be my duty. I am paid far less for my duty, as you know. This has to be for something beyond my ordinary duty.” The major nodded appreciatively. “Very good,. Lieutenant! You’re catching on quickly. Yes, this task to which we have assigned you is, indeed, beyond the call of ordinary duty. We have firstly chosen you, because we are fully assured you can accomplish it with dispatch. Secondly, it is not something you need tell another soul about—do you understand me?”

As one gentleman to another, Ferguson understood immediately and nodded gravely.

The major rose, took some tobacco from a gold-inlaid ceramic box and put it in his pipe, tamping it down, then lit it, and only then turned back to Ferguson as he held the pipe in his hand.

“The American colonies, Lieutenant, are like this smoking pipe. You know as well as I, if I should take a sudden draught, I might choke myself up, on so full a pipe as this. That is precisely what we have done so far in engaging them in conflict. As we rapidly set our forces on them, whether the vastness of the terrain or the inclement weather of the American wilderness, great, hostile circumstances have conspired against our generals, and the colonies have somehow given us more smoke than our nostrils and throats could handle. We are choking on America and the Americans! We thought if we could just take one sudden draw on the American pipe, we could consume the tobacco all at once, but you really don’t smoke that way, if you are a sensible man. So…[as he eyed the lieutenant closely] this is where you come in. You sip and savor tobacco, slowly, never quickly and in posthaste. Yet we here still aim at a quick resolution of the conflict, to be sure—-for the king demands it-—but we must go round at it by a different way. You, Lieutenant, are that sure way round!”

A thousand pounds in hand was completely forgotten. The lieutenant’s face showed dismay and bewilderment. Himself the way to a military victory over the American colonies? How could that be achieved? He was only one man!

“Before you try to say something,” the major continued with speed, “I mean simply this: you will shoot down their leader like a stray dog, and the insurrection will cease.”

The major fell silent and stood watching the lieutenant’s reaction.

William Ferguson, he observed, did not flinch, or at least controlled any sign of inward reservations. “A seasoned assassin would act this way,” he thought privately. “This is our man!”

A moment or two passed, and the lieutenant stood looking back at the major.

“Well?” the major prompted.

“Of course, I will do it, since I am under orders.”

A look of slight disappointment flickered on the major’s face. He soon replaced it with a pleasant smile.

He nodded, then turned his back on the lieutenant, took several leisurely puffs on his pipe, then went to the guns he had displayed on the wall nearest them. He took down a rifle that was decorated with silver sheathing and exquisite ornamentation.

“To bring down a fine, well-bred animal, for the fellow is not quite on the order of a street cur, you should use a fine weapon. Take this from my own collection. I’m sure you will find it satisfactory.”

The lieutenant took the rifle and examined it carefully and respectfully, as a violinist would a Stradivarius, but finally shook his head reluctantly.

“Thank you, sir, but the aim is everything. I have the aim. It is a gift I have perfected. I can use any ordinary rifle to do what my king has called me to do. I only require to make a slight alteration and it will do exactly what I wish it to do. As for this, it would only atttract attention to me, don’t you think?”

He handed the rifle back to the owner, who stared at him, but could not counter his words.

The major immediately became all business the moment he returned the rifle to the wall rack.

He swept up a document from the desk. He glanced at it, then thrust it at the lieutenant. Ordinarily, his aide would handle such details, but this was a special audience.

The major looked like another man, he had turned so grim.

“Read it carefully after you leave me! It will give you all the details of your mission. I advise you, in parting, to show it to no one, and keep every word of it to yourself. The ship that will transport you will be leaving tomorrow morning, at dawn. Be on it in civilian garb, or be court-martialed and hung! The captain and crew have been expressly commanded not to question you, and to keep from engaging you in conversation. Should American privateers attack the ship, and any of the crew fall into their hands, they will be able to tell their captors nothing substantial. You are the mystery civilian passenger, that is all. And you would be well advised to drown yourself, in that extremity. You won’t be issued a second draught of these orders! We would send the ship with additional warships for escorts, but we don’t wish to attract untoward attention of the enemy. On arrival on the American coast, at the first safe port you will disembark and proceed as an ordinary citizen with ordinary clothing. You know the rest. If you need to be admitted to the front lines of any of our forces, apply to page four, section four, which will be sufficient to gain you access. Good luck! Happy shooting! Any questions? I’m sure you have them, but I think you would best keep them to yourself. This—I’ve said enough.”

The officer, evidencing a furious, cold emotion that the lieutenant found inexplicable, then turned his back.

The lieutenant, orders in hand, was obliged to salute the major’s back, and then he turned smartly, and strode out, his cheeks burning.

Enraged at the brusque treatment, it took him some minutes of vigorous walking in the cold air outside the courts of the war ministry before he calmed down sufficiently to think better of the offer. After all, he had a thousand pounds in hand. That sweetened the task considerably. And he would bank it immediately. It wasn’t a rich man’s living, perhaps, but even if he should remain a lieutenant in rank it would pad his retirement comfortably, so that he could live to a ripe old age in nice circumstances. If he failed? But that was unthinkable. He was enlisted for his sure aim, that alone. He knew he could get the man they wanted. He only needed to get to the colonies safely—and the rest would be soon written in books.

But who was the quarry? Astounded, he realized the major had not divulged the “dog’s” name. He had merely described him as “leader” of the American rebels. The Americans, he knew, had many leaders. That was their big problem: disunity, and no one man to speak for them. Having rejected the king as sovereign over them, they wanted no other single authority to tell them what to do. Now in a war for their independence, that trait was working against them. So which leader was he to assassinate?

He stopped beneath a lantern, for the winter was deep, and the dark descended early in London, to examine his orders.

Then an assassin’s instincts took over, and he realized how exposed he was to passing crowds, and loiterers, of which London boasted a multitude at every hour of the day and night. He hurried to his officer’s quarters, and bolted the door on his room. Only then did he light the lamp and spread out his orders.

What he saw make his eyes widen even more in his pupils, which were already enormous. Normally blue, his eyes looked coal-black beneath his thick brows.

“Washington! Of cou--!” he cried, then hushed himself.

He had heard of him. Who hadn’t? Son of a rich landowner in Virginia, he had failed at various military endeavors, such as the one with General Braddock in 1755, yet had been chosen to lead the American forces by an overwhelming majority. Why? That was something no one in Britain could fathom. He was the great hope of the vastly out-gunned and untrained American colonies—the most unlikely man to succeed in their cause, yet somehow he had managed to protract the war beyond Britain’s endurance. Was that failure? Ferguson wondered. Certainly not! Was it “Providence” then? Whose side was God on anyway? The rebels’ or the king’s. But here Ferguson’s reasoning faltered. He had seen far too much earth in men to see divinity in God. He was a man of sure aim—and that was all. At least he thought that was all. Yes, he had heard the rumor that no bullets could touch Washington—supposedly proven in a battle of the French and Indian War fought 8 miles from Ft. Duquense on July 7, 1755, when General Braddock, lost all his officers except Washington and witnessed 714 men of his 880-man army annihilated. But it was only a rumor! He had yet to see anyone step forward and testify who had been a participant in the battle. Of course, you couldn’t expect dead British soldiers and their commanding officers to step forward, and that left only the French and their Indian allies—and of course they weren’t speaking, having won the battle outside Ft. Duquense but lost the war!

The return ship carried a man who was not officially allowed to leave his cabin the entire voyage. Lieutenant William Cuttleford Ferguson was still travelling incognito, but this time everyone knew everything about him. Word, particularly bad news, travels amazingly fast, and the whole British army and navy assigned to the American theatre seemed to know “Ferguson’s folly,” as it was being called, and they all took it personally, as if he had perpetrated an abysmal disgrace on them by sheer perversity of character.

The lieutenant remained closeted in his room aboard ship the whole voyage, except to walk the deck during the midnight hour. He wished to see no one, and no one wished to see him. There were rumors afoot, he knew without having to hear specific conversations, that the crew designed to slit his throat and throw him overboard.

“Let them garrot me and feed me to the fish!” he thought grimly. It would be a mercy, and spare him the Court-Martial and hanging for treason or dereliction of duty, or whatever else they charged him with.

To pass the hours, he drank heavily. The captain, without being asked, supplied his every need, even this one, without murmur. All he had to do was place an empty outside his locked door, and it would be replaced within the half hour with a full flagon of gin.

The candles burned like his memories, day and night. Ferguson lay on his bed, a glass in hand, and sleepless eyes open, unable to keep a certain scene from replaying itself over and over in his mind’s eye.

It was the scene that had changed his own destiny, and two nations—one an established empire and one soon to even greater—forever.

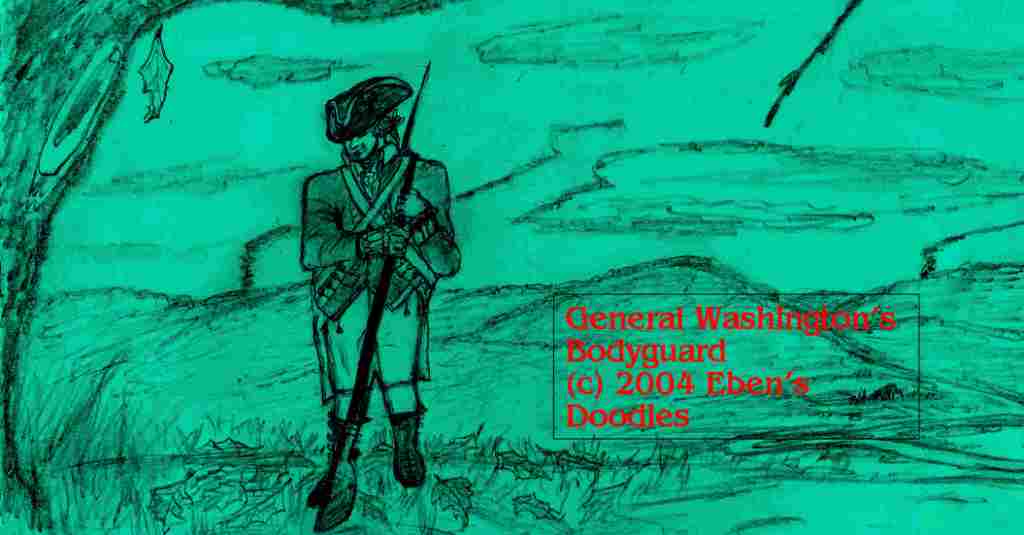

He had used Page IV, Section IV, of his secret orders to gain access to the front lines of the Royalist forces, and in a campaign near Yorktown he had seen his quarry move into his gun site. The target's bodyguard was a young booby, who had grown weary of the job, evidently, and had made himself conspicuous, stationary, and easy to pick off.

Ferguson knew he would not miss the man’s heart, since he hated head shots (they were so messy).

But each time the quarry moved, Ferguson simply shifted forward, still within Royalist lines, to reset the man in his line of fire.

It was a stunning moment, as he took sure aim once again, ready to fire this time, and then realized—-as if a thought could be lightning and strike through his brain in an instant as this thought did--that no general on his side would ever behave as this American general-in-chief was behaving. Not only that, but he saw the man himself—-standing over six feet, narrow shoulders, wide hipped, unsmiling-—not handsome yet unmistakably regal and commanding in carriage.

Lt. Ferguson had never been called upon to shoot or assassinate anyone of this caliber before.

Never! You had simply to set your eyes upon this man, and you knew beyond doubt that this was a true king, a noble prince, a lofty sovereign—unlike any Britain could claim. Only it was majesty of a strange sort—-majesty mingled with a humility not seen in Great Britain for ages, if it had ever been seen there since the Devil himself had taken up residence in London!

This was a king who got down in the trenches with the commoner! Imagine King George trying that! He wouldn’t even think of it!

He tried to pull the trigger but somehow he could not. This was no mean “dog.” Rather, King George, though dressed up in all his finery, was the wretched cur! And this man—why, he was no other than a great untitled King!

Finally, soaked in sweat, the failed assassin threw down his rifle and walked away from the front lines, the general coming from his tent to congratulate him, then standing bewildered as the lieutenant walked past him without explanation., except to mutter in passing, “No wonder those Frenchmen and their savages couldn’t get a common bullet to strike him down at Ft. Duquense!”

Meanwhile, in London at the war ministry, a certain major in charge of Ferguson’s secret mission anxiously awaited news of his own fate, consuming bottle after bottle of much better liquor than his sharpshooter could obtain aboard ship.

They did not meet in the same rooms as before. The major went to the Tower of London where Lt. Ferguson was being kept after being hurried there directly on arrival.

The major’s burning question was evident in his inflamed eyes even before he could open his mouth.

It was the lieutenant’s turn to give him his back.

“If you had seen him, you would have done the same thing as I did,” he declared. “I can tell you, Major, with such a man on their side, our cause is lost! Doomed!”

The major exploded. “What do you mean, you—-you despicable traitor! Despite what you’ve done, America can never succeed against our vast imperial military resources. We’ll have you quartered and hung for this outrage! You had every chance, and you threw it all away! And you stole a thousand pounds for absolutely no service to the Crown, on top of your abject treason!”

William Ferguson turned round, having been called traitor once too often.

“You can have every pence of your rotten money back! I want none of it staining my hands! As for this “service” to the Crown—“ he started stripping off his own buttons and insignia, throwing them at the major and the walls. “—it is a lost and corrupt cause, this abject fighting and trying to subjugate the free American colonies! Tell that to His Royal Majesty King George—one we all know is nothing but a mad and petty tyrant not fit to drive a dog cart to the brewery, much less lead a great nation into the hell of war!”

How could a sensible man disagree with that?

Ruined, Major Mudgett left the lieutenant to his fate, and went to his own—-dismissal from his post, the loss of promotion, and professional disgrace.

After locking the doors to his private interview chamber, he took the silver-embossed rifle hand-crafted in Damascus. Before he took sure aim, he drank his last bottle of fine Scotch whiskey, sipping and savoring it like he did with tobacco.