CHRONICLE OF THE BELZONI EXHIBIT, VOL. IV, RETRO STAR

C H R O N I C L E

O F

T H E

B E L Z O N I

E X H I B I T

A N N O

S T E L L A E

1 8 6 5

Part I

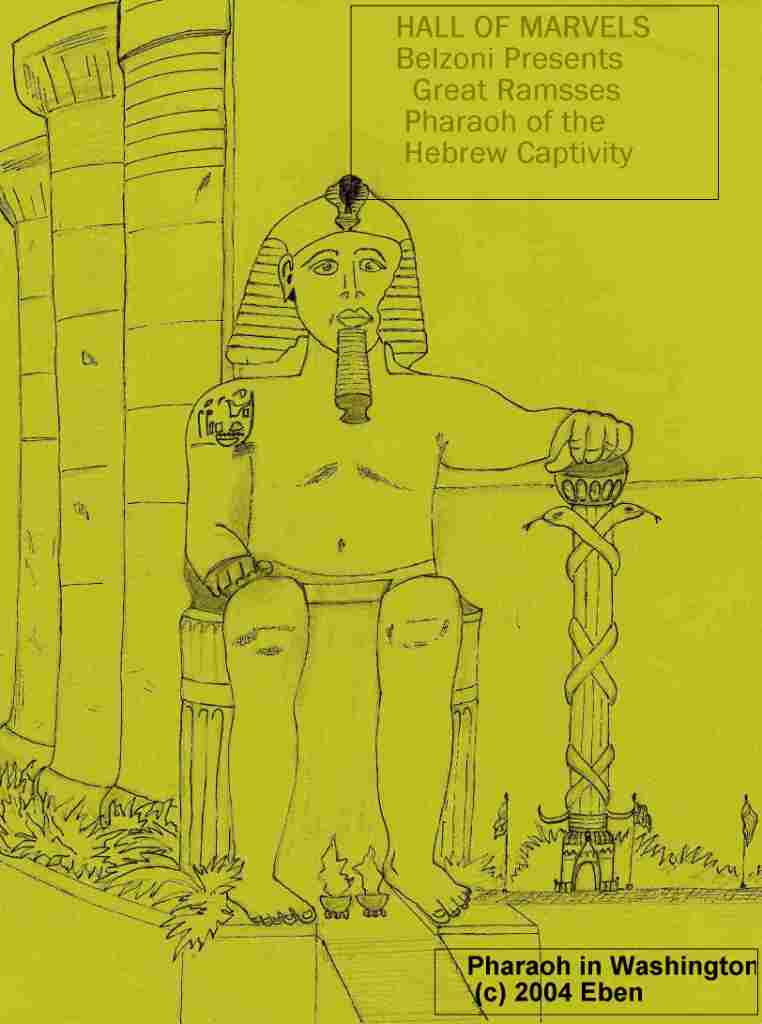

The Colossus of Thebes

First transported to London from Egypt by the famed explorer and popularizer of Egyptian antiquities, Giovanni Battista Belzoni, the fragments of the pharaoh’s gigantic statue had lain in the dust for over two millennia in Thebes (ancient Weset or Waset, "The City," after being toppled by an earthquake.

Restored to society in the splendor of the British Museum in London, the giant head created an instant sensation. All the high-born and titled nobility flocked to view it, and poems were penned by the leading Romantic and neo-Classical poets as well as the Poet Laureate. The highly controversial but renowned Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley viewed the great torso and was said to be greatly shaken by thoughts upon the passing and transitory glory of such kings as mighty Ramesses of Ancient Egypt. He composed his immortal “Ozymandius,” in which he misrepresented what he saw when he described the pharaoh as both fierce and sneering when he was actually smiling and portrayed by the ancients as benevolence itself. Perhaps, Shelly had in mind a fierce Assyrian king like Sargon, or the equally savage Sennecerib who tried and failed to take Jerusalem? But that was in 1810. Since then the fragment had stimulated a great thirst for more such antiquities, to be put in display in the foremost museums of Britain and France and, eventually, America. To satisfy this demand Belzoni spent a large portion of his own fortune gained in selling discovered antiquities in bringing out from Egypt yet another piece of the fallen colossus of Thebes. Hailed at the world’s greatest statue, which in its day had weighed 91 tons, the Ramesses was just as impressive when distributed to various European and American capitals. A torso complete with throne in London, a foot in Paris situated not far from the cenotaph which would house Napoleon’s betrayed remains, arms and a knee in Berlin, and finally the head in Washington!

A mishap occurred, however, in transporting the crated head from ship to dock at Washington. A ladies’ finishing school had sent out several young ladies to preview the famous head if possible and write a report for the school publication, but their carriage and horses were too close to the work apparently, when the horses started in alarm as the huge box swung toward them. Before the ladies’ driver could pull the carriage back away, the horses fled, taking the carriage right under the lowering crate. The crate could not be stopped quickly and descended further, catching and then crushing the carriage with tons of granite. With many men on hand for the operation, there was immediate help to pull the victims from the wreckage, and it was found that they had suffered injuries but were still alive. As for the Belzoni artifact, damage was to the head, which lost a portion of its left cheek and headdress, which were assessed on the spot as not enough to prevent the scheduled showing.

Everyone who saw the exhibit in Washington City said it was the greatest marvel of statuary anyone could hope to see in a lifetime. Belzoni had outdone himself in presenting the head. Using giant frameworks and pulleys, the head (which was mostly intact) was placed upon a high pedestal, then the remainder of the lost figure was created on the spot with ingenious use of plaster applied to a wire and wood framework. Painted to resemble the original, it was difficult to see where the stone left off and the plaster began. To all appearances, Ramesses now sat in all his original splendor in the exhibition hall, transported across thousands of leagues of ocean and time by the miracle of modern steam power and modern engineering.

Such massive crowds pushed to get into to the exhibit that police were forced to turn hundreds away, for fear their combined weight would collapse the building’s floors. Day after day the huge attendance continued until the Count was assured of a wonderful profit, enough to pay off a stupendous debt owed the shipping line and the army of laborers that had been used in Egypt and then later in America to load and move the colossus.

All the capital was talking about the Ramesses head, and of course Mary Todd Lincoln the President’s wife had to see it. It wouldn’t do if quality were all seeing it and she, a Todd, a banker’s daughter from the best society in Kentucky, wasn’t in the foremost of them! Even her backwoods-born and bred husband had acknowledged the Todds, saying that they were important people, because they had two d’s in their name, whereas God was content with one. But she fretted because it had arrived just at the successful termination of the War, and it was questionable whether her husband wished to see it now that he was fully engaged in the festivities of the victory. Should she go along with a few ladies and her boys? Or should she get Abraham to attend her? It took some persuading, but she wouldn’t give up—knowing that the president by her side would be most impressive when she wore her latest new gown to the exhibition.

A date was set for the viewing on April 13 and approved for their attendance, with the next day given to a showing of The American Cousin, a darling English play she had heard about that she knew the president sorely needed to see to bring up his spirits. She herself felt almost uncontrollable in her emotions of late, and thought the play might take her thoughts off so many things and give her a moment’s respite at least of self-forgetfulness. How she had been attacked in the papers for her “extravagance” and “frivolity,” when actually she had done everything she knew of to cheer the president up. Did her detractors ever consider that she had to keep the president’s mind together on the weighty matters of state and war? How could he maintain his sanity, if she went around in a sad face and dowdy clothes. The war was terrible, and anything to lighten the chief executive up was absolutely needed. New furnishings, new dishware, new frocks from New York’s best shops—yes, they cost thousands—but look at the effect! She had preserved her husband’s mind during the whole dreary, mad fighting of North against the South! Wouldn’t anyone give her due credit for that?

Except for the president’s bodyguard and a few White House officers, the president and his wife entered the building alone with just a few attending them for the private showing. Not even Giovanni Battista Belzoni was present, for he was stranded in New York. The Italian vessel equipped with steam-powered side-paddles he had taken was caught by a gale at sea was forced to return there for repairs. Mary Todd, pleased by the reception she thought her gown and fur-trimmed cloak and hat had received from the crowd outside the hall, hardly thought about the Rameses ahead. It hardly mattered to her now anyway what Belzoni had concocted. She was scheduled to look at it, and she would look at it, but she already was thinking of the next day’s outings and dinners and what she would be wearing.

The dimly lit hall, which had been a local Temple of the Noble Order of Osiris, a men’s only club with secret Scotish rites mixed with Egyptian themes, was fully decorated to resemble a classic New Kingdom Egyptian temple at Thebes. The massive granite columns lining each side were actually plaster covering wire frames strung around timbers. Mary Todd, without any interest in ancient architecture, naturally thought the columns were real artifacts taken from some heathen temple over in Egypt. The whole figure that towered above them, seated on a granite throne, that too seemed real. Lit torches provided the illumination, and the scent of smoke made Mary Todd put a scented handkerchief to her nose as she proceeded slowly forward on the arm of her husband the president.

It seemed to her that they would never get to the official viewing stand—the whole avenue between the columns seemed intolerably long to her nerves in her arches.

Her ankles and the flats of her feet began to ache, it seemed, long before they reached the viewing pavilion, which was elevated and needed to be climbed. Why couldn’t she just view the statue from the ground floor? She wondered irritably. Why must she be forced to climb up all those steps? Who was important here anyway? She or this hulking statue? The viewing pavilion was just some silly contrivance of Mr. Belzoni’s, she thought, without any necessity for climbing it, other than Belzoni’s convenience in taking an impressive picture of the presidential party taking the view.

But the president would love the opportunity to take two or three steps at a time, she knew, instead of the mincing, little steps he was forced to take when escorting her in public places! But would she? No, she would refuse to go up in her long skirts. Why, she might step on her petticoats and trip and tumble down the staircase! What a spectacle that would be! Her enemies would love to see her disgraced. She wouldn’t risk it! A shirt-tail relation of hers—her name she couldn’t recall at the moment—had broken her neck that way at her own wedding! Well, she wasn’t about to follow her relative’s example during the victory celebrations!

Surprising his wife, the president paused. He hadn’t even glanced at the golden pavilion and its ornate steps. Instead, he stood and took in the figure above right there from ground level.

“This is the cruel and murderous old pharaoh, they say, that enslaved the Israelites of Abraham,” a colonel remarked to the president. “If not him, this one certainly looks he could play the part!”

“Yes, that’s the evil, old tyrant who defied Moses,” Mary Todd chimed in, now that her memory had been refreshed. “Isn’t he awful looking, darling? What a beast of a man! I dare say he is the most hateful specimen of humanity I ever laid eyes upon!”

The sunken-eyed, haggard, rail-thin Great Emancipator said nothing as he gazed back at the Great Enslaver presented in all the glory of his kingship and flourishing, manly strength. “Most hateful?” Not as he was presented! Naked to the waist, powerfully built in body, the king stared out at a vast eternity, smiling as if he alone would always rule the earth and no one existed, past, present, or future, who could ever take his power and glory away. Indeed, he looked like the god he presumed to be. Everyone else, beside him, was made to appear pitiful and the size and significance of mice and ants, and it was that sheer gigantism of the statue that intimidated and even angered people so much they thought the pharaoh was ugly when, on the contrary, he was most handsome, virile, and young.

“Can you imagine, sire, this old pharaoh was considered an imperishable god, by himself and his people,” commented the scholarly colonel. “He enjoyed absolute power, and wouldn’t know what we mean at all by a freedom-loving Republic and a nation founded of the people, by the people, and for the people. Back in his time everything existed for his sake, not the other way around! In other words, he wouldn’t like us and our country at all!”

So used to Mary Todd’s fidgets as to not to notice them, Lincoln nodded and acknowledged the colonel’s wise remarks (though he could see nothing old in the face, only eternal youth in possession of full powers), but said nothing as he returned the pharaoh’s stone-carved gaze. For all the gimcrackery of Belzoni’s showing, the thousands of years represented in the stone head was still readily felt, and Lincoln distinctly sensed he was, indeed, in the presence of the long-dead but once mighty monarch. For several long moments his big, cavernous fleshless ribs rose and fell in deep breaths and exhalations as the present and the pharaoh considered one another and, as it were, took each other’s measure.

“How low and drained I feel in my vital powers now that the war is over!” he thought. “Yet how quenchless the powers that shine in this ageless stone face and head!” It was a marvel to him, for no two beings could be so different, as he could see they were. “You have existed in this form for thousands of years, and no doubt will far exceed my posterity and be around centuries and centuries for people to gape at when I am no longer remembered! Oh, we of the Union cause gained some note of late in the papers and the scholars’ chronicles for the successful conclusion of this great and tragic American War, but you, O Great Ramesses? You left temples, statues, obelisks, pyramids, and grand cities crafted of beautiful stonework, no doubt, all to tell the world beyond you of your unsurpassed greatness. They are fallen mostly to ruins now, the scholars tell me, but your head remains to this day, and I am seeing it—proof you surpassed the test of cruel time and passing change! Perhaps you will be smiling long after I am turned back to dust, yet—“

For some reason that escaped him, he fell to recalling his own past: back to the days of his father and the frequent, difficult moves of the family in ox-drawn wagons from homestead to homestead in the virtually lawless wilderness, then recollections of his mother, who died young, then his own days trying to eke out a living in farming and store-keeping, then joining with a man to take vegetables and other produce down the Mississippi to New Orleans twice, with a visit to the slave market that planted a fearful hate and revulsion in his heart forever for slavery when he saw a colored man torn from his screaming wife and children and sold to a cotton planter taking him far away to East Texas. How could a nation endure, he thought then, if one man were free and another man was cattle? The Founding Fathers, wise as they were, had bequeathed a tragedy and an abomination to their descendants! Would the immense, dark stain of slavery ever be wiped from the brow and face of America? And at what cost?

But, interrupting his thoughts, what was it he then saw in the strangely suggestive flickers and shadows that abounded in the poorly-lit hall? Some vast shape was forming before his eye, clouding the face of the statue. Was it torch smoke? He thought he saw a city in the future, Washington City, its bright domes and monuments, constructed like Grecian and Roman temples—with even a great masonry elephant standing astride a long boulevard of trees and grass—but the city soon flickered, as if struck by a bolt of lightning. Its white marble darkened to black and mortuary black by the soot of many fires, and a yellow ribbon flew round it, with troops stationed to keep anyone from entering! What? And what was he seeing carried, as a last relic from the dead capital? It was none other than his own massive figure, cast in granite!

It couldn’t be! he thought. America would never, never consider himself so great as this Ramesses as to cast him in immortal stone. America, he knew, would never attribute such greatness to him just because the war was won and the slaves were emancipated. He was a mere rail-splitter! He must never forget that humble trade—for his countrymen would never forget it. But more significantly, what had he dreamt when he thought he saw the capital consumed by the spirit of death? It was a most dreadful sight!

He began to shudder, feeling cold that wasn’t there. They hadn’t been there for only a few moments when Belzoni’s exhibition attendants, on cue by the man in charge, struck cymbals and then came forth, garbed in Egyptian style garments, forming a procession that was meant to give ancient honors to the “god Ramesses.” The fat-bellied “Egyptians” who looked like they had been freshly recruited from the ranks of stevedores on the wharves of Washington City were almost comically attired with plumes glued to their shaved heads and wearing golden breaches to which cow tails had been attached. Belzoni had miscalculated on the degree of credulity in Washingtonians--for those present had seen enough P.T. Barnum to smile with amusement instead of gape with awe and wonder.

Lincoln, his lips curling slightly, forgot his fancies of the death of Washington City and endured the simple entertainment for what it was, then when the last cymbal was struck, he tipped his hat to the colonel, and that was a cue to the presidential party to retire. Mary Todd Lincoln, by this time, was all but in a collapse of nerves, what with all the hideous banging on brass pans and barbaric African drums and the stinging, acrid torch smoke in her eyes and nostrils causing her to not to breathe for fear she would choke to death. Nothing in the whole exhibit had impressed her particularly, and she only wanted now to get away as quickly as possible.

When they were outside, safe in their carriage with a somewhat inebriated bodyguard sitting with the driver (both of whom had slipped into the shadows round a corner for a drink from a bottle the bodyguard carried), she turned on him. “Why were you shaking so, dear?” she cried. “I thought everyone would notice before I got you out of there. Are you catching something from all the fogs and dampness of Washington City? I hope not! You simply must not call of going with me to the play tomorrow! Everyone is expecting us to come, for it will be such a good time!”

“Now don't fret over me, I am fine,” he assured her. “I wouldn’t dream of canceling our going tomorrow. What is the name of that play you want us to see?”

Diverted, Mary Todd rattled off the name and then proceeded to give him the plot as their carriage turned back to the White house, the extremely clever story which she had heard from a friend who had already seen it performed in Philadelphia. “You’ll adore it, dear! The performance, I’ve been assured, is positively a scream! When Lolly Hampton told me about it, I could have died for laughing and had to have smelling salts brought or I would have fainted dead away!”

Part II

Twenty Minutes After Ten

The day following the visit to the B elzoni exhibit, April 14 (a day on which, forty seven years later, the world’s greatest ship would be fatally struck on her maiden voyage) Mary Todd Lincoln and her husband were escorted into the presidential booth at Ford’s Theatre for the new play’s presentation. Mary Todd was pleased at how the booth was suitably decorated with flags, and she was further pleased to see the effect her new gown was having, drawing every eye in the theatre as they entered their booth to sit down. After they seated themselves, the whole assembly took their seats and the play began.

Weary with the cares of his presidency and the effects of the past war, his sunken eyes and loose, sagging skin of his face showing the world how very tired he was, the President attempted to turn his attention on the play, which everyone was raving about in Washington City. He had a good view of it, since the box overlooked the stage, but his utter exhaustion could not be denied. The President was soon nodding in his chair, unable to keep his attention on the comedy. He loved good-hearted humor, but his exhaustion made it impossible for him to sit very long before he became drowsy. Mary Todd, used to his ways, did not care to prod him, as she was so taken with the play she hardly noticed how her husband was faring.

After five minutes the bodyguard slipped away from outside their door and went across the street for some more refreshment since his bottle had run dry. He had been in that saloon once before that day, and he thought a few more drinks wouldn’t hurt. It was a dull job for an active, young body standing duty outside a door for hours on end. Nobody would be the wiser if he took a little break, he reasoned. While the bodyguard was at the saloon the assassin, the actor and revenge-minded, Southern sympathizer John Wilkes Booth, saw his golden opportunity to strike a last blow for the defeated South. At seventeen minutes after ten, he went up to the second floor to the door of the president’s booth. He tried the door, it was unlocked, and he entered with a loaded, cocked pistol.

He observed Lincoln and his wife, their backs turned, oblivious to his quiet entrance.

Standing behind the president, he saw there would be nothing to prevent him, and at precisely twenty minutes after ten he shot the president at close range, firing directly into the back of Lincoln’s massive head.

Mary Todd jerked around at the explosion of sound struck her, saw the assassin and the smoking gun, and still had the presence of mind to scream, “He has murdered the president!”

How many times had the chronically fearful woman rehearsed this line? A dozen times? A hundred? Her practice, in the wee hours of the night when everyone else could sleep but she lay nearly breathless with anxiety, now paid off in a flawless performance of the Aggrieved Wife of the Mortally Striken President.

The whole theatre erupted in chaos as the sound of the gun, the high, feminine scream, with the words of Mary Todd Lincoln crying murder. It immediately stopped everything on stage as the actors and actresses stook transfixed in their places. The assassin, realizing his escape back out the door would be the first to be cut off, dashed past Mary Todd Lincoln to the rail, seized it, and threw himself over. He meant to leap to the stage from the box, which was a short distance away, and he would have made it safely except that his boot spur caught in a flag and he fell, breaking his leg and tearing the flag as he struggled to get free. Falling onto the stage, he staggered free of the tattered flag and broken leg and all escaped out the back of the theater and somehow mounted his horse and got away, heading for the house of another Southern sympathizer.

The presidential box was almost immediately filled with men, who carried Lincoln out to a house across the street where he was laid in a bed in the master bedroom. Doctors were summoned, and White House officials also came to the room where the president lay unconscious and clearly dying.

The doctors observed the wound and agreed the bullet could not be touched.—it was too deeply embedded and he would expire at the first attempt There was no saving the president, yet they did not wish to hasten his end by unnecessary surgery. Rather, it was best to make him comfortable as possible and await the inevitable. Mary Todd was so distraught by this time, she was impossible to have in the room, and by orders of the physicians she was removed from the room. Her throwing herself on the president and crying uncontrollably could not possibly help him, they reasoned.

Part III

"Where are you taking the Colossus, my good fellow?"

Lincoln lay motionless in the borrowed bed, his bandaged head propped on a big pillow, wholly unconscious to the world, but he was dimly aware of a great pain in his head. He had no idea that he had been shot, having seen nothing of John Wilkes Booth. Unknown to him, the American people were already grieving, hearing of his mortal wound.

He drifted in and out of dreams, which were very strange even to his fading mind. He saw a colossus (was it Belzoni’s?) being removed from a tall-pillared, white edifice as huge flaring lights were directed on the work that made the night brighter than day. Somehow he got closer and was surprised to see, being borne by giant machines instead of gangs of hundreds of sweating slaves as Pharaoh’s colossus would have been borne, his own image. How could that be? he wondered. The very idea of anybody making such an image of him was appalling. What had he done to deserve such a fate?

“Where are you taking the Colossus, my good fellow?” he asked a man standing there.

“To Manhattan, the Big Apple,” the man replied, before squirting some chewed Copenhagen from the side of his mouth.

“Why?”

“This old town is done for! Don’t you know?” the man cried, dumbfounded. “Look for yourself!”

The rail-splitter and lawyer looked, and though, he saw smoke and soot on some of the buildings, the fires had evidently been extinguished and there was no general destruction in the strange, vast and beautiful metropolis spread before him. With flares of working crews everywhere as they removed artifacts from the most important structures, it was marvelous in construction to his eye, with many noble buildings all standing in flooded with light before him. The only truly odd and disturbing thing was the ring of flashing blue and red lights and searchlights he could see in the distance and the constant wails of high-pitched horns.

“What city is this?” he marveled, for he had never seen anything so grand, not even in New York.

“Are you crazy?” the man cried. “Don’t you know it’s Washington, the capital—or was, I should say? Are you—?“ He peered at Lincoln. “Say, you must have been hit by the death rays-—that explains it, your brain is affected!”

“I don’t see what you mean!” he said to the man, though he did feel rather hurt in his head. He put a hand up, but could feel nothing, only a strange numbness.

The man looked exasperated. “The people—they’re all stone dead, man! Here on the surface they’re all blasted, nothing but bones and some skin here and there where the rays didn’t hit! Somebody let off a neutron bomb on the Beltway—and they say there’s another set to go off any time to take care of any survivors and medical teams! The whole subway system is shut down and blocked, of course!”

“’Neutron bomb’?” Lincoln repeated. What could that be? he wondered, but he didn’t get an answer, as the man was very busy directing the operation.

The man moved away, but saw Lincoln still standing by the side. “You need to get moving, if you are to get out of here before they wall it all up permanently. The UN is taking over, and this is a no-man’s land, off-limits to the public from now on! From now on Chocolate City is in New York—an apple covered with tax payers’ chocolate instead of Coney Island caramel-—hahaha!!“

The supervisor squinted in the bright lights as he peered closer at Lincoln. “Are you sure you aren’t related to old Abe? You sure are a dead ringer for him! Hey guys--”

The supervisor turned to call a few of his workers over to see what he meant by comparing him with the statue, but already the whole scene before the dying Lincoln was fading away, and darkness closed in as the workers gathered round to stare at him where he sat in a big white sheet.

Copyright (c) 2004, Butterfly Productions, All Rights Reserved