The Return of William Washington Shoey

As the Red Star turned its attention to America the war with Japan neared its bloody end. With Soviet Russia completely in its grip, Great Britain fatally subverted, Nazi Germany destroyed, and Japan about to be, its rays penetrated deeply into the American heartland, even into the heart of the generation that pioneered the country with heart-breaking labor and endurance beyond belief. If the Red Star could find an open door into a man like William Shoey, that should be proof no American was beyond its reach.

William Shoey had been a shoeshine boy all this growing up years, at a grand hotel downtown Kansas City, but after a few months of honeymooning at various homes of relatives, taking his savings and his bride he set out to find a new life for himself and his family to be (for Bessie was bearing their first child). Everybody in their families were against the move, but when William’s mind was made up, it was truly made up. Shoe shining was all he had-—and with his education-—all he could expect to hand down to his sons. You would think that with a name like Shoey he would be content with his trade, but no, there had to be a better way for someone like William who had a vision of what he could be if only he could get out of the “sinful flesh pots" and temptations of city life in Kansas City! Unlike many young men, William loved God and church life, and was always in church where his parents took him three and four times a week for services. Unlike others his age, he was a clean-living young man with principle, with the strength to walk by the painted women hustling on the street and never go in the open doors of the saloons that numbered in the hundreds up and down the avenues leading to the hotel where he worked and the old brick house which the Shoeys shared with six other families. Abiding by the Ten Commandments and the Golden Rule, he was righteous! Not for him drinking and womanizing, and carrying on in pool halls and smoking in his time off from his job. Not for him! Agriculture, working with his hands in the soil God Almighty had created, was what he determined to turn to his advantage. The William Shoeys were going to be farmers and be a real part of the American success story, or bust! When William Shoey heard in town about the farm property up for sale when talking to the postmaster, and that nobody wanted the land because it had no well and it would go cheap to the first buyer, plus it was located a stone’s throw from the Oregon Trail and had a bona fide buffalo mound on it, he was sold on the idea of being its owner! What could be more American than being a farmer on pioneer land alongside the Oregon Trail? He was sick to death of being called “boy” at the hotel when he was a grown man, being kicked in the behind where he sat on his small stool, and thrown nickels for his hard work like a dog is thrown tidbits! He was just as American as anybody else could claim to be, he knew. His grandpa had fought in the Civil War on the Union Side, risking his life to escape his slave master in Mississippi in order to gain his freedom. After that the war, taking the few dollars the army paid him, his grandpa had moved the family west, hoping to make it all the way to Oregon. But his wife took sick and died in Kansas City, and there they stayed until the next generation, when William Corey, the grandson, came along and caught the pioneer fever!”

It was hard to tell, whether he was more proud of that or Plain View Farm at times. Plain View Farm was his special creation—it was nothing until he came and worked and sweated years to make it the wonderful and beautiful homestead it was. William Washington Shoey was a true pioneer, in the true sense! He came with almost nothing, just his dream of starting a new life for himself, his wife, and his coming family. He stuck out the cold, the heat, the insects, hardships of all kinds, and slowly built up one of the prettiest little farms in the county. They never grew big, but they were still there—while many other farmers up and quit during the hard times—especially during the long drought and depression years. But Pa Shoey was no quitter. He was a man to try anything to make a way—if it was auctioneering, he was the man, if it was well digger, he was the man, if it was fence builder or part-time railroad laborer—he was the man. Somehow they made it during the toughest times, with God’s help, wisdom, and strength—and Plain View Farm was still there, while so many others like them had been blown away with the Russian thistles!

Where and what is Eudora? Well, to start off, Eudora, population less than four thousand, is situated in the northeast corner of Douglas County in Kansas where it intersects with Johnson and Leavenworth Counties. The farmstead lay about 100 miles from Kansas City, Missouri, between Kansas City and Topeka, and Lawrence was the closest big town. A “stone’s throw” from the Oregon Trail, which was a Trail of Dreams, many of them broken, but many of them fulfilled, was its chief distinction besides being able to view three counties from the property at one time. This is where William Shoey and his young bride settled in the early 1900s on half a farm split for quick sale to any comer.

The opening scene shows the back of the Shoey farmhouse, a simple white-painted wood frame house of two stories, porches front and back that William Shoey and an uncle who knew carpenteering put up with hard work and fifty dollars of reject boards from a Eudora lumber company. On the north side is the cistern, where rainwater from the roof is collected. The south side has a bit of a garden, with flowers Ma keeps watered with dishwater. The kitchen at the back has its wall cut away in order to show the audience what goes on in it day to day. The house and the props are painted white, and some items are actual farm artifacts, though others are paper or cardboard.

The time is in the 1950’s, during the Eisenhower years and there is money to be made in the big cities for the middle class and, if you are a big farmer, government subsidies. The Shoey farm doesn’t stand to gain much of anything, being too small, but God has blessed the Shoeys, and they always have enough, and some left over to share with the needy and the Indians who still pass by on way to their various reservations. Bessie has done a lot of living and has gray in her hair, and her children have all been married (and one, son Arthur, she has lost in a plane crash). Her girls and remaining son have all married and moved away, mostly back to city life. Son Leroy has chosen to be a Methodist minister, so there is no one to take the Farm now that Arthur is gone. Yet life goes on. And one daughter has married a missionary and is on the mission field with her children. Bessie feeds several painted wooden chickens on the way to the fence corner. Then an Indian Family comes to the fence, and she goes back to the house, gets some food wrapped in a flour sack, and hands it to them. They take it and move away toward the Oregon Trail as Bessie watches them go.

The kitchen looked like this: A sink and counter top that have seen years of heavy duty cooking and cleaning. A wood stove with a “reservoir” for holding and heating water for baths or coffee; a woodbin by the side of the stove. A small two or three person breakfast table with red checkered oilcloth on it, and two beaten-up old wooden chairs. A broom and dustpan. Some dish towels made of Pillsbury flour sacks. Two wires or ropes can be strung above and across the kitchen set, so that a blanket can be hung on it and changes can be made in scenes, since the kitchen will have to be a bedroom at times.

PLAIN VIEW FARM

A Musical Drama in Three Acts

THE CAST

William Washington Shoey—“Pa”

Bessie Lincoln Shoey—“Ma”

Seven Daughters and Two Sons of Ma and Pa Shoey:

Pearl

Bernice “Bee”

Myrtle

Cora

Lulu

Estelle “Star”

Arthur “Artie”

Ruthie

Leroy “Lee”

In addition to:

Young Spouses several grown daughters

Narrator (a young woman, in stylish ”city clothes,”

Probably a granddaughter of Ma and Pa Shoey)

A Plains Indian family

The Chorus

__________________________________________________________________ PLAIN VIEW FARM

Act I

Scene 1

Place: Plain View Farm, a farmstead four miles from the small town of Eudora, Kansas, population about 4,000, located in eastern Kansas between Kansas City, Missouri and Topeka, with Lawrence, Kansas, the closest big town but not close enough to influence Eudora significantly—since the little town is a strictly traditional small-town community like the majority of small towns in Kansas with its large number of Amish and Mennonite farmers.

Time: The mid-Seventies of the last century.

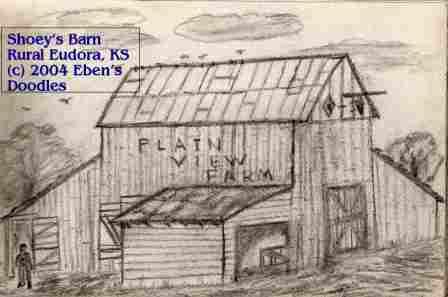

(We see a kitchen, with the wall removed to show its furnishings, at the back of a white, two-story farmhouse. Off to the side is a painted barn, with the name PLAIN VIEW FARM proudly lettered on it in white, but the paint is peeling on the barn and house, and there are signs, like the broken windmill, that the Farm is no longer being kept up as it once was, because the man of the place is missing.)

(Ma Shoey, an old widow living alone after an eventful life as wife and mother, likes to get away from the now lonely kitchen sometimes and stand out in the yard where the prairie breezes blew, and where the yard fence makes a corner. As she goes she throws some corn kernels she has in her apron to the painted wooden chickens in the yard. Then she stands at the fence and looks out westward toward the Oregon Trail, as if she can see covered wagons still travelling in a long, dusty line along it, heading for Oregon, Washington, or California.)

(An Indian couple and their son about seven years old come walking up to her. Smiling as if grateful to see a human face again, she goes to the kitchen, gets some pie and fresh-baked bread, and real butter and a jar of her strawberry jam, which she brings wrapped in a Pillsbury flour sack, and hands it to them along with a jug of milk. They drink the milk on the spot, then depart as quietly as they came.)

(As Bessie stands in the yard holding the empty milk bottle a flute begins softly like a gentle breeze on the grass. It turns slow and melancholy, something like the blues of Kansas City, then gradually joyful and rich, concluding in triumph and celebration, while turning back to repeating the first soft notes.)

(The Narrator goes to her podium at the side of the set while Bessie remains standing at the fence after the Indians depart.)

Narrator:

(Speaking for Ma Shoey’s own thoughts) “What a strange country this Kansas was for me—a young city girl like I used to be! Back home we rode on streetcars, shopped in the big department stores with the lunch counters where colored folk like me and family couldn’t sit, and bought our dresses and hats ready-made. Kansas City had over one hundred thousand people, and lights everywhere, with traffic going day and night. How different it was for me here—no smoke from all the chimneys, no traffic noise, and no tall buildings! And, of course, the people here all white except for us—and not the kind of whites either we knew in Kansas City! Oh, no! These here are people called Amish, who seek to live holy in their own way. Why, all the men in beards and work overalls without buttons, and the women be wearin’ that pretty little lace cap on their hair pulled tight and pinned to their heads—Amish, they call themselves— people come clear from Russia to worship God here and live their own way. They keep to themselves, and let us be too—so we get along all right. Well, as my Ma used to say, it takes all kind of things to make a good gumbo. Ma, she came up from N’orleens to visit her aunt in Kansas City, saw Pa at a service in church her aunt took her to, and one thing led to another! Now where was I? Oh, yes, we had done moved to another country, it seemed, coming out to Kansas! I could plant my own flowers and not have to get them at a florist shop, and we had trees and a garden, and big fields of corn and wheat, and, of course, all the pigs, sheep, chickens, mules and horses. My, how quick life was in Kansas City, and how people moved! Not so here! Thanks to all the Amish people in Kansas, who won’t give up their wagons and horse carts, we hardly ever saw a car on Main Street in town, even in the Twenties. Before I left the city, when the graham cracker factory wouldn’t hire me at thirteen, I got work as a day maid. Ironing, dusting and mopping floors, it was hard work but I could earn more than a workin’ man’s dollar a day in those big houses with the pillars out front the rich white folks lived in, but here, there was no ready money like that! Oh, no, we had to grow somethin’ first, then sell or trade it for something’ else we wanted! That was no way around that! If you wanted to eat, you growed it, then you could eat! Well, we sure learned to grow our own food, and the rest—well—we did without a lot of things! Yet we always had enough to eat from my big vegetable garden Pa always plowed up for me and the things I canned, and whatever cow and chickens we could spare we butchered. The winters here come pretty cold and with a strong, barrell-rollin’ wind—Good Lord, does that wind ever stop blowin’ in Kansas?--but we had plenty reject wood scraps from the lumberyard in Eudora and also some coal for the parlor stove on Sundays that Pa gets in town from bartering his turkeys or sheep or whatever else he has for what we need for fuel. He was always so good at getting what we needed, even in the worst times of the Depression and the great Drought. Many farmers quit and took what they could, and set out for California. But not Pa. He aimed to be a good provider for me and the children. And he had faith in God to see us through the hard times, and God was true to His word and saw us through! Yes, Lord, He saw us through!”

(Ma Shoey puts her hands to her temples, in the way she does to steady herself, she is so overwhelmed by her memories)

“ But thank God for good health and the strenth of body to do the work every day morning to dark it takes to keep a farm like this goin’—like pounding out the pound of gristle in a quarter pound of tough cow meat for dinner when you just hoed the garden and chopped wood for the cook stove and milked the cows!--and also for the church home we found in Eudora four miles from the Farm. We couldn’t find a Holiness-teachin’ Pentecostal fellowship like our big church in Kansas City anywhere near us, but we found a little God-fearin’ church of people with a missionary bent where the Gospel is preached Sunday after Sunday by Pastor Dent and lately by his preachin’ son! Pa was always at church before anybody else, happy to fire up the stove to warm the sanctuary and do other things that needed done, and so they over-looked his color—yes, they did! The church board appointed Pa substitute teacher in the Sunday School, and finally they chose him Sunday School superintendent, the only one of his color permitted in the county that she knew of!

“But how strange it was at first movin’ out to all this wide open air and empty ground in Kansas—farming and homesteading, with no well, and just rainwater to drink and bathe in and hardly a tree in sight till Pa planted all these lilacs and trees to make the Farm beautiful and keep the wind down some in the yard so my clothes would stay pinned to the clothesline and now blow clear into the next county! It wasn’t an easy life by any means, goin’ from big city life to country life, a wagon and horses for transportation, chickens, cows and sheep to care for, nine children on top everything else!”

(She pauses, her back to the audience, shudders, and seems to remember something she doesn’t want to remember)

Narrator: “But Pa—I miss you so much! It’s been full twenty years since your homegoin’. I don’t know why the Lord has let me live so long without you! It’s hard, Pa, out here alone, for a Kansas City girl. But there must be a reason the Lord has given me this long by myself—maybe prayin’ for all our grandkids—maybe—“

(Still shaking her head at the memories, the old woman returns to the kitchen, a blanket is drawn up and the scene concludes).

Scene 2

(The windmill is half-built to show that this is the beginning of Pa Shoey’s reign as the farmer on Plain View Farm. The barn is finished, however, and has the name PLAIN VIEW FARM half-painted on it and a ladder beside the unfinished part).

(Ma Shoey is no longer the old woman thinking over the loss of her beloved life-mate and the many events of a long, busy life. She is a young married woman, so she is wearing a fancy “church goin’” bonnet left over from her Kansas City days to keep the wind out of her ears when she is hanging up wash in the yard. A little girl tugs at her Pillsbury flour apron as she sweeps the floor. She pauses to rest, as she is pregnant again. Another little girl comes in to join them.)

Narrator: (She opens a notebook). “Daughter Estelle writes in her old Farm diary: “It has never been necessary for Ma Shoey to own many aprons. Just a good square floursack with the edges sewn up and bleached, folded into a three-corner way, and, pronto, Ma had her apron! These sacks she sewed into pillowslips, dish towels, and diapers for the baby. Even with Ma's lye soap the red and blue ink that was stamped on them was next to impossible to remove. The result was that “Pillsbury’s Best” was prominently displayed on the seat of the baby. Whoever heard of store bought diapers anyway?’”

The Chorus comes in around the young mother, though she doesn’t see them, and sings: “Pillsbury’s Best”—a name of the big flour company stamped in red and blue on the bottoms of her youngest girls.

(The Chorus finishes “Pillsbury’s Best,” and Ma Shoey stands with a hand on her bulging midriff, as she appears to contemplate the movements of life within, her eyes close, her lips moving in what looks like a silent prayer.)

The Chorus sings: “Oh, God, Let it be a Boy!”

Narrator: “The ways of Providence, particularly with women, can be mysterious at times. God turned a deaf ear yet again to Ma Shoey’s prayer to save face with her talkative neighbors. Little Pearl, Bernice, Myrtle, Cora, and Lulu were followed by Estelle—all “Pillsbury’s Best”—but not quite what she requested so urgently with an eye on the neighbors.”

Scene 3

Time: After 1919

Place: The yard and farmstead, in spring with young trees and a few small, newly planted flowering lilacs painted on stand-up sheets of cardboard. The windmill is completed to show some passage of time forward from 1919, the year the First World War when the house was built and the family moved in from a shed that first sheltered them the first few years.

Narrator:

“Plain View Farm sure wasn’t much of anything in its bare beginnings! Just acres and acres of Kansas prairie and tall grass that once saw nothing but buffalo, hunting parties of Indians, and then a long line of covered wagons heading west! It took a man’s dream, plenty of hard work, and heaps of determination, to make it what you see now! And Pa Shoey—he was a great one to dream and then do something about it! No well, no trees or shrubs, nothing but empty land stretching into the distance toward the Oregon Trail—most folks would have passed it by, except Kansas City’s most enterprising shoeshineman, William Shoey, who had an eye for making something valuable out of whatever life threw a colored man with only a third grade education. True, it did have a buffalo mound on the property and lay nigh the old Oregon Trail. Pa was thrifty. He grew good corn and wheat on that old mound. They say the buffalo used to stand guard, heads facing outwards, hour after hour through the nights, to keep the young ones in the inner part of the circle safe from the wolves. Well, the children said they could still feel it , by walking slow with their bare feet. But there is something else—the best in Pa Shoey’s estimation. The land rises a little higher here at the Farm. It’s about the only place around where you could see so far. When Pa Shoey found he could see some of three big Kansas counties at one time—Douglas, Johnson, and Leavenworth--that was his reason for naming the farm PLAIN VIEW FARM! How many farms could you say that about? Pa Shoey figured he had a special place and worked to make it look like one by planting trees, lilacs, and even putting up a special entrance gate with colored rocks and cement! Then came trouble over in Europe, and World War I broke out. Both Ma and Pa Shoey knew of family members who were going into the Army, but they wouldn’t take family men like Pa Shoey. He went to volunteer in Eudora and proudly told them how his grandpa had fought in the Union Army against General Lee. No, they told him, they wanted men his age to take care of their families and grow the food needed to feed the army fighting over in France. So Pa Shoey went back to Plain View Farm and planted “victory corn,” “victory wheat,” and even “victory potatoes”! Every wagonload of corn and wheat and potatoes the Shoeys’ horse and mule took to Eudora became his proud share in the battle. In four years the war was over, won by America’s ‘doughboys’ coming into it just when Britain and her ally France were about worn out in the struggle against the big guns and armies of Germany and Austro-Hungary. Everyone was so happy! They thought it was the end of war—and there would never be another like it. A year later, Plain View Farm’s house was finished. They moved from the little shed to the house—what a wonderful feeling that gave them all, to be living in a real house of their own! Come Spring, all nature seemed to celebrate the housewarming with them!”

“Daughter Estelle writes: ‘From the time the first furrows were creased across our fields, until the corn was planted, our farm had an air of bustle about it. We could sense the pulse of things growing. They were days of change. At first the trees were tinged a faint green and suddenly, as if overnight, they broke into full leaf. The air came in heavy and fertile with promise through open doors and windows. These were happy times when we could wake in the morning and not have to lace shoes, but just run barefoot!’”

The Chorus sings “Barefoot in Spring”

Act II

Scene 1

Place: PVF’s master bedroom downstairs, just off the kitchen, with Ma in bed, being handed a newborn by the doctor) Narrator: Number Seven is supposed to mean God’s perfection. Well, in God’s perfect timing, not man’s, a boy was born to Ma and Pa. Long awaited, he was the pride and joy of the whole family and would have been spoiled, except that he seemed to be born with noble character. And he was special beyond that: he was born in January, the very day a storm struck the Plain and family awoke to find Plain View Farm transformed into a beautiful, enchanting scene no poet could have described adequately. Ice covered everything, trees and house and barn. This child in winter, Artie, was indeed born with a special sign from God. But a sign of what? What did it mean? Time would tell. At any rate, Ma got her boy at last. Her fervent prayer may have been delayed by the charming, vivacious, big-hearted Estelle, nicknamed “Star,” but her seventh was clearly a boy. His name—Arthur—an angel of a lad of the most quiet, grave, and sweet disposition. Soon followed another girl, a handful of activity and selfless devotion if there ever was one, as if to make up for the “mistake” in Arthur’s gender, and she was named Ruth and called Ruthie. But again Providence turned mysterious and chose to temper the staunchly feminine line of the William Shoeys with the male species, perhaps for Artie’s sake, giving him a brother, Leroy—“Lee”—the last of the nine Shoey children but certainly not—with his steadfast, caring ways—the least.”

Chorus sings, “Three from Nine”

Scene 2

Time:

Early 1900s

Place: PVF’s yard. The children play games with a ball or, if they are the smaller ones, they draw pictures with sticks in the dirt of the yard.

Chorus sings “Farm Life.”

(Ma interrupts the playing children to give one a broom, another a pail to feed the chickens, another a dish pan of water for the flower bed. A school bell sounds in the distance. The girls all hurry to get their books and lunches and march off toward school down between the seats of the audience, Ma Shoey looking after them at the fence corner.)

Scene 3

Place: PVF kitchen

Narrator: “Estelle writes: ‘The Saturday bath, while the kitchen was warm, required bringing in large wash tub, filling it with rain-barrel water that we heated on the range or took out of the reservoir. The lack of privacy and draughts from the opening of doors make it quite an ordeal. We first bathed the baby, then the next in line of years. Hot water was added after each bather had finished to warm up the water for comfort and effect for the next to step in.”

(The children come running back home, throwing their books down. Ma pulls out a big tub into the kitchen.)

Chorus sings “Saturday Bath”

(A blanket curtain is raised to admit one family member after another, each taking her or his turn, starting with the baby, and ending with the oldest, Pearl. Suds are thrown up over the blanket as the person taking the bath takes the plunge. Ma carefully folds the dirty clothes for the wash basket or goes to fetch more hot water from the cove of the stove, if there is any left. At least once the blanket falls unexpectedly, there are screams, and the blanket is hastily raised. At each young bather finishes, she (usually she) comes out dressed in her Sunday Best, Bible in hand and stands “at attention” in the yard. They sit down together in a cardboard or real wagon, with Pa shaking the reins on painted or imaginary horses.)

Narrator: “Estelle writes: ‘Most of us remember the spiritual life and atmosphere of our home. The concern for and dedicated efforts to live a Christian life. This we remember in our home. The family devotions each evening and on Sundays if we couldn’t make it to church because of road conditions. This didn’t happen very often because if the roads were too wet, we’d go by horses and wheels. If too much snow for the car, it was by horses and sleigh. All week we worked to prepare our clothes, shoes, lessons, and the conveyance so that we should be found in our local congregation on Sunday.’”

Chorus sings “Sunday Service”

Scene 4

Time: 1920s and 1930s

Place: A painted train platform in Eudora, with EUDORA, KANSAS printed on the side of the little one room depot’s wall. The whole family is present to see certain oldest members off to school. The oldest, high school age children go and stand and put their sad faces in the window of painted train car as they look out at Ma and Pa and the rest of the family.

Narrator: “The time comes for the oldest Shoey girls to set out to attend school at Word of Life Academy, many miles distant in Topeka. Estelle writes: ‘After grade school we were privileged to attend Word of Life Academy, a Christian school, a trip we took mostly by train over a hundred miles from home. Always tears were shed as we left home. As we sat ready to leave, and the younger ones standing by with Pa and Ma, the finale was to sing “Praise God from Whom all Blessings Flow”. It left a deep impression and was a long-remembered ritual.’

“Always mindful of his own third grade education and having to quit school to earn money for his folks, Pa was determined we would all get the best education possible. The Academy held up Christ and was high in scholastics, and cost $300 a year for each student’s tuition, room and board. With so many going from the family, it seemed impossible, yet Pa found it was within the Shoey budget if each Academy-goer worked out in homes or on farms during the summers, earning money to help with tuition, as well as worked in the cafeteria during the school terms. Pearl, first, worked out as a housemaid, even plowed fields for a dollar a day! The Academy might as well be a thousand miles, as far as the family is concerned. They will not see one another again for months, perhaps not even at Christmas if funds for travel are too short, and there will be no expensive phone calls either. Estelle writes: ‘Not only did the nine of us receive Christian education, but somehow Pa and Ma put aside money so that event the grandchildren could take advantage of the opportunity of attending a Christian school. A Christian respect for the nation was instilled in us, and Pa especially stressed Christian leadership and gave tribute especially to Abraham Lincoln the Emancipator. He told us all about our great-grandfather who had fought on the Union side. He always told us how Lincoln at the end of the war received a delegation of freed slaves and they presented him with a beautiful Bible. He was really proud knowin’ something few white folk knew—that it was colored folk who built the U.S. Capitol while they were still held slaves in Maryland, a slave state that surrounded the District of Columbia. We thank God for parents who loved the Lord Jesus, read the Word to us, practiced its teaching, being faithful, and taught us to do the same. We thank God for all Pa did for us. We thank God for you, Ma. As the Bible says in the Psalms, “The godly shall flourish like palm trees; those that are planted in the house of the Lord are under His personal care. They shall bring forth fruit in old age and be vital and green.”’ ”

Chorus sings “Off to the Academy”, along with the intermixed melody of the old hymn that the Shoeys always sing in these partings, “Praise God from Whom all Blessings Flow.”

Scene 5

The family is all gathered in the yard in spring when the lilacs, now tall, are flowering round the yard, the girls and boys grown up and out of school, all dressed in their Sunday Best and standing . Ma and Pa are already seated front and center, their forms grown stocky with the years, and there is gray in their hair. The Narrator calls out the names of the seven sisters and two brothers, as if giving them directions in the best way to stand, as a photographer out front makes the motions of taking their picture.)

Narrator: (She finishes calling out names and the positions they should take, and they take her directions as if she is an assistant to the photographer. The older girls especially are the most stylish, wearing store-bought clothes from Eudora or, better yet, Kansas City.). “There! You all look mighty fine! Pa and Ma have worked, loved, and prayed unceasingly, and the fruits of their long labors have finally matured. They have brought up a loving family on the Kansas prairie, right through the Depression and the worst droughts and dust storms of the ‘Dirty Thirties’. The nine beautiful children have been nurtured in the love of Christ, trained in holiness, educated in the skills needed to make a success of their lives and do their parents proud. The seven sisters have become attractive and marriageable young women, all loving Jesus as Savior and Lord. Artie plans to go to college and maybe enter the ministry, though he wants to help the folks on the Farm and will buy a piece of land right across the road in the adjoining county, making Plain View Farm a two-county property! Somehow getting all their varied schedules and locations to agree, they’ve come back to the old Farm for this special reunion and family picture-taking.”

Chorus sings “Family Portrait”

Scene 6

Time:

Late 1930s and Early 1940s

(The picture-taking over, the photographer goes, and young men appear and go and pair off with various girls after a respectful bow to (and an approving nod from) Pa and Ma, the still seated parents. The first young man, Bob, dressed in a spotless white flight cap and pilot’s jacket and white shoes, comes to court his chosen sweetheart, Pearl, and first hands a little airplane to Pa, who makes it swoop about in the air before he crashes it nose-down on the floor for fun. Pa throws his arms around the young man. Artie comes up, and Pa puts his arms around the both of them as he stands proudly surveying his little kingdom. But soon Bob has to pull away, and he leads Pearl from the set.)

(Next, Bernice stands before the audience. Ma goes out, comes back dressed in her everyday housedress and apron to water her precious flowers. Bernice gazes at her while the Narrator speaks her thoughts in “Ma” by Bernice. When she is finished with her tribute to Ma, a young man in a stylish hat bought in Los Angeles comes and takes her hand, and leads her away. They proceed slowly as if in a wedding march, the young man’s eyes straight ahead and Bernice’s modestly lowered.)

(When Bernice’s tribute is finished, Lee the youngest comes out and stands awkwardly, for he is still a boy. Pa replaces Ma in the yard, and he sits on a stool mending boots and shoes for resale, for all his daughters except Ruthie have all moved to the city and won’t need them anymore for farm work. Even Lulu is just staying a few more days, intending on returning to Kansas City to find a job as a secretary. He looks up at the sky through the open sole of one of them, and gives a doubtful shake of his gray head.

Scene 7

Place: Upstairs bedroom of the farmhouse.

(A bed on which two sisters, Lulu and her youngest sister Ruthie are lying. Lulu is tossing about, her eyes closed. She suddenly sits up and cries out soundlessly, while Ruthie, her rag doll in hand, is awakened, and appears frightened. The flute music resumes, then dies away, abruptly.)

Narrator: “They crashed! They crashed! Artie and Bob crashed! Oh, the smoke, the fire! It’s that plane a man sold Bob—it wasn’t fixed after he said it was, and he told him to give it another try!”

(Ruthie, clutching her rag doll, can’t make any sense of it. Lulu stares at her, looks as if she wants to shake her, then covers her own face with the blanket. The scene ends with the return of the flute music, but is sad and gentle, like a funeral’s.)

Scene 8

Time: Early 1940s

Place: The PVF farmyard and house.

Narrator: “But dreams are dreams. They may not come true. Thinking it the wise thing to do as the older sister, Lulu keeps silent about her terrible visions of the night, and Ruthie forgets the whole incident. After all, Lulu thinks, who would believe her? Who, indeed? Life goes on, as Lulu occupies herself moving away from the Farm to a new life in Kansas City. On the other hand, something is not right these days with Pa. He has grown more and more upset and happy. His pastor’s children, for instance, can do nothing right, according to his view. He is also upset with half of Eudora, particularly the merchants who he thinks are against him just because of his color, and who, in his opinion, are nothing but a pack of reprobates masquerading as Christians. He refuses to let Ma go to the various stores in town where they’ve gone for years now—and this is hard, for they need flour, sugar, salt, and coffee, and Eudora is the only place she can go. Pa finds out that the church softball club is going to play the Catholic church’s softball team on Sunday afternoon, and throws a fit, speaking out against it everywhere. Playing ball on Sunday was offense enough to him! But playing against Catholics? Even worse, his own pastor, he hears, doesn’t go and read the Bible and pray all day between conducting two full services, oh no! He actually goes fishing! Pa has only to see his pastor passing on Main Street and he is filled with uncontrollable fury. What has become of the self-made man and loving father who has planted all the sweet and beautiful lilacs and the trees that have made Plain View Farm so attractive? Now, instead of enjoying his blessings, he drags up the past, when this and that happened to him when he was back shining shoes in the hotel in Kansas City—how one customer came in and gave him a mean, hard kick in his rear as he sat shining another customer’s shoes. How everybody laughed, as if it was some big joke! Pa was so furious, but what could he do against so many? He never forgave them, and the man who kicked him—who, being white, was not forgivable in his opinion! Ma is concerned, very concerned, at this change in the man she loves and has given so many children to.”)

Chorus sings “Fishin’ on Sunday”

(While the Chorus is singing, they are acting out various pastimes—practicing casts with a fish pole, reading funnies in the paper, playing cards, all while Pa Shoey's looks on with disapproving grimaces, a Bible in one hand and a switch in the other. The flute gives out wild catcalls and devilish whoops and Pa, unable to endure the merriment any longer, swings a willow switch around and scatters the laughing Chorus. He chases them out off the set, as soon as he narrator has spoken what he is shouting.”)

Narrator: To the firepits of Gehenna with them! May they all burn in eternal damnation, the sinners!”

(Ma comes out of the kitchen, looks sadly around, shaking her head. She stands facing the audience, her head bowed. Pa comes back out on the set, his clothes all rumpled and a big stick in his hand. He stands face to face with Ma, like a snorting bull before a red cape.)

Narrator: (speaking for Ma) “Oh, Pa! What’s gone wrong with you? God might take one of us, if we don’t stop all this judging and putting down of people, especially our dear Pastor!”

Narrator: (speaking for Pa) “Woman, I don’t know what you’re talkin’ about! Besides, do you think you’re some kind of preacher, that you can preach to ME? Maybe you’re forgittin’ you speaking to the Sunday School superintendent!”

Narrator: (speaking for Ma) “Oh, Pa!” Ma exclaims. “You don’t have to listen to me then! Listen to the Word of God. You know the scriptures better than anybody around, don’t you? Well, I shouldn’t have to remind you then that the Apostle Paul writes this to the Galatians, “I marvel that you are turning away so soon from Him who called you in the grace of Christ to a different gospel…” And he also writes to the same wayward folk: “I have been crucified with Christ; it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me, and the life which I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave Himself for me.” And then you know of course how he wrote, Ephesians 4:31:32, “Let all bitterness and wrath, and anger, and evil speaking be put away from you, with all malice. And be ye kind one to another, tender-hearted, forgiving one another, even as God for Christ’s sake hath forgiven you.”

(Pa, defiant, stands shaking his head, and claps hands over his ears).

(The music, now unmistakably ominous, resumes, and breaks off with a clash of cymbals as if of thunder. Water drops begin to fall. Ma stands her ground while Pa ducks his head and dashes off the set. Ma remains, and seems to be pondering something only she knows as her eyes blink away tears, and she twists her apron in her hands.)

Narrator: “What is Ma thinking might happen to her beloved Plain View Farm family, what with Pa gone so bitter in his heart and ways toward people? Does she know something of what is in store for them? Artie—what about him? He has gone off to war in the South Pacific, joining the Navy. Little Ruthie—the soul of family devotion—is still staying close by the home fires, and Leroy is too young yet to venture forth on his own, but her other children are getting jobs, finding mates, and scattering to the far corners, to California, to New York, even to Brazil as a missionary’s wife. Yes, what does the troubled heart of Ma discern in the clouds swirling overhead, darkening the sky over Plain View Farm?

INTERMISSION

Act III

Scene 1

Time: January 1947

Place: A small house between Seattle and Tacoma, Washington State.

(Pearl Bigelow, a married woman and mother of six, is kneeling beside her bed, in her home in the Puget Sound country of Western Washington.

Narrator: The eldest Shoey daughter, Pearl Bigelow, is now a married woman with a brood of her own. She and her vigorous, outgoing husband Bob have moved to the West Coast, and Bob, an avid flyer, fisherman, and a carpenter in a shipyard, has begun building a new house for his wife and family. Best of all in her eyes, he loves the Lord she loves. Yet, with all her responsibilities in her new home and at church, she does not forget old Plain View Farm and the dear souls still on it—Ma, Pa, Artie, Ruthie, and Lee. Particularly, she prays for Pa who has been growing worse, not better. It is spiritual sickness. He won’t forgive people what they did to him in the past. Because of it he has even developed a bad stomach condition, and grumbles and blames it on Ma’s wonderful cooking! Yet Pa, Pearl reflects, is a very strong man, not likely to change. She has seen him do things that still amaze her to think of. Fixing a fence without wire cutters, he would bite the wire in two! Would it take to change his mind and heart, after he had become so fixed on hating the sinner instead of just the sin? So people had treated him bad back in the old days in Kansas City—throwing him tips that were too small to pay for his service and shaming him at the hotel when he shined shoes for customers—why drag that all up to poison the present, which God had clearly blessed? Look at the wonderful family and grandchildren he had! Look at Plain View Farm, where he could spend his remaining days with Ma, Artie, Ruthie, and Lee around him? Why couldn’t he just forgive those white folks, especially since most of those men were probably dead by now! Why wreck things in Eudora, with all the merchants too? She knew every one of them, done business with them for years, and was on good terms with their womenfolk and children. Why, they weren’t trying to treat him any different—their wives would hear of it and put a quick stop to any such thing! Eudora wasn’t perfect toward colored people—there were attitudes some white folk had against folk like her, but you found that everywhere. And Pastor Dent—you couldn’t find a more loving shepherd of God’s flock, preaching faithfully service after service, visiting the elderly and the sick and the dying, always available to pray for people’s needs! Yes, his boys weren’t perfect angels always, and but whose children were? Fishing on Sunday and playing ball—they weren’t the worst things that people could do on God’s holy day. What about backbiting, criticizing others, and blaming folks? Why go and spread a spirit of unforgiveness around everywhere to make a day darker than it was?

Grieved, one morning Pearl sank to her knees as she went to prayer. Her Bible, much used, has just fallen open to the book of Hebrews, where she happens to read in the 12th chapter: “For whom the Lord loves He chastens, and scourges every son whom He receives.” An old, forgotten incident then returns to mind. She recalled when she was a young girl, standing in the barn almost hidden by a big haystack, she saw Pa come in the other end, but he didn’t see her he was so intent on what he was doing. He had a mule he couldn’t budge, but he was determined to budge it anyway. Finally, he got so mad he grabbed a stick and threw it, and it struck the mule’s head, striking it right on its eye. Shocked, she watched a strange thing happen to her Pa. Just as he was about to bind up the poor mule’s wound with his red bandanna, a sort of glowing red spark shot in the barn through the open door. He didn’t see it, but she did. It paused over her Pa’s head, then beamed a red ray down at him, and he seemed to stiffen in his shoes, and his eyes glowed red for a moment. The little red star then shot back out the door. The next thing she saw Pa do was throw down the bandanna and stomp off, leaving the mule.

She pondered the verse and the added recollection, wondering what the Lord may be telling her, and then her eye goes to another passage in the same chapter: “Pursue peace with all people, and holiness, without which no one will see the Lord, looking carefully lest anyone fall short of the grace of God, lest any root of bitterness springing up cause trouble, and by this many become defiled.” She begins to tremble, as her thoughts center on her beloved Pa. “Who else could the Lord be speaking about?” she thinks. “Who else?” She cries out to God. ‘Oh, Lord, you may take one of my little ones, even our youngest, Joyce, if that is what it takes to save Pa from his bad condition. Only—give me the grace to bear it.’ The moment she uttered these words, so costly for a mother to say, her heart flew free of its terrible burden she had carried many days and nights. Then she knew for sure God heard and would save Pa.”

(Pearl slowly rises, wipes her face and eyes with her apron, and goes to the cupboard nearby. She opens it and goes to reach for something when a toy airplane tumbles out. She picks it up off the floor and puts her hand to her face as she looks at the model airplane.)

Scene 2

Place: The set of the farmstead, with a dim light upon it, as if a cloud is covering it.

(To break the somberness of the previous set a bit, the flute plays, and there is a definite rhythm and melody of the “Blues” about it. It grows louder, climaxes, and then slowly fades. The Narrator does a little dance, slowly, to the music. She take a long, flowing scarf and performs her dance with it. When the music is over, she returns to her post at the podium).

Narrator: “Plain View Farm will never be the same again. Cold winds of change, some born in the darkness of the human heart and some in the depths of an evil star, have blown across it. As Estelle wrote: ‘Your children and children’s, O beloved Plain View, will become middle-aged, then old. The living will become the dying. The strong will become the weak. The dreamers will become realists. The process will never go in reverse, for the old will not become young again. Therefore the Gospel of Jesus Christ offers not only a frame for beauty, but offers beauty for the hour when life has been rubbed naked of its luster…” A wise saying is this: when it is darkest the stars shine the brightest.”

Scene 3

Time: January 9, 1947

Place: The Bigelow home in Washington State.

Narrator: “Pa and Ma had celebrated their Silver Wedding Anniversary on the Farm August 13, 1933, in the midst of the Great Depression. They would both live to celebrate their 50th on the Farm too; but between the Silver and the God ran a dark, icy cold river, full of rocks that could stop break any boat that tried to pass. Lulu was right. Death lurked in the river, and caught the two young men dearest to Pa’s heart—Artie and Bob. For Pa to change, to turn back to forgiving folks instead of condemning them, one death wouldn’t have done it. One wouldn’t have been enough.”

(Pearl is lying on her bed in her home. She has her youngest child Joyce with her in bed as the little girl (about two and a half years old) naps. There is a knock on the door. Without her glasses she answers the door and the pastor of the church enters.)

Narrator: “Mrs. Bigelow, I have sad news for you. Both your brother Arthur and your husband Bob were instantly killed in an airplane crash.”

(Pearl sits back down on the bed, puts her head in her hands. Her lips are moving.)

Narrator: “Can you hear Bob’s widow? She has just spoken very softly. She has just said, ‘I have the answer.’”

(Her pastor puts on his glasses, opening his Bible to read her something).

Chorus sings portions of “Love’s Sweet Lullaby” and “In the Gloaming” Scene 4

Place: The Bigelow home in Washington State.

(Pearl and her six children. Darrell, the oldest Bigelow boy, takes his mother’s hand as she finishes packing her bag, to go by train to the funeral in Kansas.)

Narrator: ‘Don’t you worry,’ he says, ‘I’ll help and support you.’”

(A Pause)

Narrator: “There is a price to every redemption, sometimes a great price that children, without understanding, must pay. Almost two thousand years before a man from Galilee paid the price for all humanity’s sin. Now for little Joyce, her Daddy’s disappearance could not be explained. Every day she went to the door to wait for his return. Her mother tried to call her back, but little Joyce always went to the door to wait for him, day after day.”

(Joyce goes to the door, standing and waiting. The scene ends with some flute music, echoing “In the Gloaming”)

Scene 5

Time: January 20, 1947

Place: Eudora Train Depot

(Pearl Bigelow steps from the train at the depot, and immediately Shoey family members rush up to her. They all look astonished, at her smiling face and also because of the news they are carrying.)

Narrator: Pearl’s surviving brother and her sisters cannot get over the expression of peace on her face as they greet her. Why wasn’t she upset or grieving? But first they have to tell her something. “Pa,” they exclaim, “is changed! He’s hugging everybody, and doesn’t have anything against a soul, not even the airplane dealer that sold Bob that plane!” As soon as she can, Pearl tells them how the Lord prepared her, so that when the news came she could accept God’s will. It wasn’t God that destroyed the plane, she says, but He had allowed it for His purposes. That’s why she can’t feel upset and bitter about anything or anyone involved. God’s grace, the Lord has assured her, will be sufficient, and it has been sufficient! And she wants to tell them something more, how God had answered her prayer in his own time and way, but there is no time to reveal this as they all hurry off to the Farm.”

Scene 6

Time: January 24, 1947

Place: First Methodist Church, Eudora, Kansas

(The audience now participates as the audience at a funeral in church. Two closed coffins are drawn on the blankets up front, along with flowers. A white cross is set between them. The widow and her parents sit together in chairs set down before the coffins of Artie and Bob. A second podium is there, at which a gentleman in a clerical collar stands. He is Pastor Dent, whom Pa was formerly so against because of the conduct of the Pastor’s sons, conduct such as fishing on Sunday and reading the funnies.)

Narrator: “Friends and beloved family of Arthur and Bob, the entire region was shocked by the airplane crash which occurred near Eudora when two men were instantly killed. Bob Bigelow had come from his new home in Washington State to purchase a plane in Topeka, Lawrence, or Kansas City, intending to fly it back home. After finding a plane at the right price in Lawrence with an aircraft dealer by the name of Cecil Ratcliff, he and Arthur went out in the morning with it to hunt foxes and coyotes and in 13 minutes the crash occurred, leaving Bob’s wife Pearl with six children, the oldest of which is 12 years, and an empty chair in the hitherto unbroken family circle at the Shoey home. Last Thursday, January 9th, dawned for you the family and the rest of us as so many previous days had done. It was a beautiful day here in Kansas—an exceptional mid-winter day. The warming sun had risen in a cloudless sky. The morning air was fresh and invigorating and yet almost balmy. It was wonderful to be alive. Perhaps some of us wondered what the day would bring. This was the morning that had been decided upon on the part of Bob Bigelow and Artie Shoey for the taking of a hunting trip with a newly purchased plane. Artie was back home from the Navy, able to help out his folks again on the family farm, and had bought a section of land adjoining the farm for the purpose of building his own home there. But why not take a little time out for recreation? He must have thought, considering Bob’s offer. They were going to pursue a sport and a past-time engaged on by men almost since the beginning of time. These were, however, modern hunters quite unlike those of ancient or medieval times—even different as far as method is concerned from those of our grandfathers and even our fathers’ day. This latest and seemingly most exciting and thrilling way, using an airplane to pursue the wild game, was not new to Bob Bigelow, who had been flying planes for some years now and had taken up many of the Shoey family members and also those of the community. Only a few minutes later the tragic accident had happened. The plane had plunged to earth and the two young men were no longer with us. When the sad news of the tragedy reached our ears it seemed impossible and unbelievable. We, with you the bereaved, were left stunned and shocked. It seemed as though the day was suddenly gone and the darkness of a starless night had enveloped us. Truly, at this time, it is well to bear in mind, even in this tragedy, that the Lord directs the evil in this world, so that his purposes are served and His divine plans executed. Reading in Genesis, the history of Joseph gives us in the Bible a wonderful and striking illustration of this truth. To his startled brethren who stood before him in awe and wonderment there in the prime-minister’s office in mighty Egypt, Joseph said: ‘Ye meant it to evil [when they heartlessly and cruelly sold him into slavery in Egypt], but God meant it to the good…’”

(While the pastor is speaking, final music is an offering of “Taps” played in honor of Navy veteran Arthur, gradually fading away)

Scene 7

Time: 1948

Place: A cutaway of a kitchen in a small trailer in Washington State, in the same city as the Bigelows.

Narrator: “Deaths, especially of the sudden kind, are never tidy. Loose ends abound, in which lawyers often stand to profit when once involved. Cecil Ratcliff, the airplane salesman in Lawrence, has lawyers working on the case. The crash of the plane he sold to Bob Bigelow has been well publicized, and his business has fallen off so much he has to quit. He intends to get the full price for the plane from the widow, one way or another. You see, no bank will cash a check from a dead man, and Bob’s wife didn’t have the money in hand to give him on the spot what he demanded. In the meantime, while the lawyers are handling it, financial and domestic troubles overtake him, he leaves his wife and moves, unknowingly, to Pearl’s own city in Washington State. Taking her six children and the baby, Roberta, who was born exactly nine months after her daddy’s death, she goes to a picnic that her church holds at a park and happens to meet a niece of the aircraft dealer, and his name comes up. The woman gives her the address to contact Cecil Ratcliff. This is Pearl’s chance to bring about a settlement without the lawyers and a court session she believes would go against her. She is still without money, but a pastor-friend of the Shoey family, prior to this, has reaped a minor windfall of $10,000 from a crop of flax, and he intends to tithe $1,000 when the Lord tells him to give it to Bob’s widow instead. $1,000 providentially covers the price of the plane.”

(Pearl knocks on the outer door of the trailer. A woman, an unlit cigarette in her hand and her hair uncombed, looks very startled when she sees a lady is calling. After one look at Pearl she quickly drops the cigarette in her pocket as if ashamed. Pearl goes in and stands at the table at which a man is sitting. It is Cecil Ratcliff. He motions her to sit down, and he too looks startled. The woman living with him goes back into the trailer, to listen to them.)

Narrator: “’I am Pearl Bigelow, Bob’s wife. Are you Mr. Ratcliff?’ ‘Yes,’ he said. Pearl continues. ‘Mr. Ratcliff, I’ve come to hear from you what really happened.’ ‘Okay, lemme tell you then. I warned Bob about his flying too low—“ Mr. Ratcliff begins. Shaking her head, Pearl interrupts him. ‘You know what happened, and I know what happened,’ she said. ‘Now I would like to read you a paragraph from the last letter Bob wrote before the accident and left in his suitcase. My husband wrote, ‘Mr. Ratcliff is an honorable and upright man. When he does a job he does it right.” Well, that’s what my husband thought of you, and that’s what I think of you. What do you want to settle for?’ ‘Seven hundred and fifty dollars,’ said Mr. Ratcliff. Now this was one hundred dollars less than what Mr. Ratcliff’s lawyers had earlier quoted her.”

(Pearl reaches into her purse as Mr. Ratcliff, his face flushed, starts to write out a receipt. Pearl hands him something along with the cash).

Narrator: “Pearl gives Mr. Ratcliff a Gospel tract with the money, and says, ‘It’s a message about Jesus, the Light of the World. Would you read it and believe it?’”

(Mr. Ratcliff nods as he hands her the receipt. He carefully counts the money. Pearl stands. She notices the newspaper he has been reading.)

Narrator: “Pearl, in going, has noticed the newspaper headline of the paper Mr. Ratcliff has been reading at the table. It is about food riots in the starving cities of Belgium. She says, ‘You know, the world is in an awful turmoil.’ ‘Yes,’ he agrees. ‘But do you know what’s worse?’ she asks. ‘The turmoil in our own hearts.’

(Pearl opens the door, and pauses) Narrator: ‘Mr. Ratcliff, you always have a welcome to our church, and my door is open to have you visit anytime.’”

(She goes)

Narrator: “Shortly after this meeting, Mr. Ratcliff left town and returned to Lawrence to his first wife.”

Scene 8

Time: August 19, 1958

Place: The yard of Plain View Farm

(A large, white, very elaborate cake is drawn or painted on cardboard. It represents the grand cake of Pa and Ma Shoey, presented to them on their Fiftieth Wedding Anniversary. Pa and Ma sit like weary royalty on either side of the huge cake, reading letters and cards of congratulations to them. Their hair is quite lighter at this date. In fact, their hair and the cake frosting are the same tint.)

Narrator: “The house was packed with family and guests for the great celebration. But pa would not allow anyone to cut into the special cake baked by a nationally-renowned lady baker—it was too full of memory, too full of Plain View Farm and all the love that had transpired on that bit of Kansas prairie soil. It has the names of all the Shoey children, plus a steepled church and the family house and barn, but the names of Bob and Artie are marked with golden crosses.”

(Pa leaves his chair and walks slowly toward the fence corner, gazing beyond just as Ma likes to do sometimes. He smiles at some old memory, then he pauses and wipes his eyes.”

“Pa recalls how he was a small boy standing by his mother’s sickbed, feeling quite helpless, as she steadily grew weaker and weaker. Then his mother died, and his father took him and the other children over to his parents after his mother had been prepared for burial. Pa’s daddy was going to go back to the house to sleep there where the body of his wife was being kept for the funeral. Pa recalls how he said to his grandmother, “I want to go with him.” “Do you want to go with him?” asked his grandma in a kind voice. “Yes,” he said. Into the darkness drove the young father on a lumber wagon with the little boy at his side. Sitting on that lumber wagon bench with the little boy, riding slowly homeward, the father and son were talking about their loved one. Did his daddy sleep t all that first lonely night? Forty five years had passed since then, but Pa thanked God for the memory of how he had tried, in his simple boyish way, to forget his own hurt and comfort a grieving, broken-hearted parent. And never would he forget his daddy’s arms around him on that long, dark, cold night.”

Scene 9

Place: Plain View Farm, with unfinished windmill, and the house newly built and freshly painted white with its first coat of paint.

Time: 1908, before the house is built, and she and Pa are living in a shed while he works building the barn and getting the farm operating.

(Young Ma Shoey stands at the fence corner, leaning over on it, gazing beyond at the fields.)

Narrator: Ma, the newlywed, looks beyond at what she can see, the spring corn and the winter wheat sprouting fresh and green in the fields—a joy and pleasure to the eye. She is not yet by any means the old woman whose beloved husband passed away long before she too slipped away from earth to heaven at age 98. Her hair is free of any Kansas City bonnet, and she is dressed in her wedding dress in which she was married August 19, 1908. She clutches some fresh-picked sunflowers in her hand. All things, light or dark, have yet to come to pass for her, this young and untried bride of William Shoey the Kansas farmer. Nine children have yet to be birthed, breast-fed, diapered, trained, disciplined, and educated all the way to godliness, self-sufficiency, and love of God and man. Until her mission is complete in every detail, how many eggs will she gather in the henhouse? How many meals to make? How many washing and ironing days will she complete? How many gardens will she plant, water, and weed? How much canning in the stifling, hot kitchen? How much wool to card and quilts to sew for her family and the mission barrel? How many homeless tramps, or Indians, or Watkins salesmen will she feed and send away refreshed? How many sick children will she nurse? God only knows. And in the darkest night, when the worst happens to Pa and loved ones are lost and the very stars of heaven seem to fall from the sky, leaving only broken dreams, it seems, what will be left in her heart? Will the Lord find faith, hope, and love still shining bright and strong, when He finally comes with golden-winged angels and all the saints? God knows.”

(Ma turns from the fence corner and starts back to the shed, swirling her skirts like a young girl. The Narrator closes her book. Great-grandchildren and grandchildren of Ma go and stand with the Narrator, looking back to watch Ma Shoey. The flute sounds the lively notes first heard in the introductory prelude as Ma goes to her shed-house, takes an apron and puts it over her wedding dress, and with a broom begins to briskly sweep the steps.)

THE END

_________________________________________________________________ MUSIC FOR PLAIN VIEW FARM

“Pillsbury’s Best”

Gates of heaven made of this—

Pearl—first—the child of bliss!

Kansas was her place of birth,

Then came Bernice of great worth.

One, then two, gleamed like a ring:

Gem and setting for a king;

No boy as yet—Ma could have wept;

Four more girls they did accept.

Myrtle, Cora, and Lulu,

Until a voice cried out, “I’m through!”

Another daughter starred their crown,

And they became the talk of town.

Yet even Lulu wasn’t last,

The barn and house, they built up fast.

Trees and lilacs, gardens too,

But what was best, was the Plain View.

Pa, he looked and gazed afar,

Of counties, three, he numbered there;

No hill or rock could his view bar;

He saw a Promised Land most fair.

In city streets man hemmed man in,

The people squeezed so tight within;

Not so, on Pa’s Plain View Farm,

With room to spare, and none to harm!

No walls of buildings shut them up,

The children ran until they dropped;

Everywhere just rich, safe sod,

Like grace, a boundless gift of God!

“Oh God, Let it be a Boy!”

“It better be a boy this time!”

Our dear Ma said one long, hot day.

“Five pennies? They don’t make a dime.

Just one good boy—what would I pay!”

Ma cooked and scrubbed, and cleaned the house,

She gave her flowers’ daily douse;

The stove wood chopped, the girls fed,

She labored till their time for bed.

“Come on, Ma,” her daughters cried,

As they clung close by her side;

“Read us from the storybook,

How Jonah made a whale’s hook!”

“No,” said Myrtle, Number 4,

“I want ‘Joseph in the Well’”.

But Number 5, as well as Be,

Chose ‘Daisy Bell Lost in the Dell.’

Dear Ma shook her weary head,

And bundled them right off to bed;

Laughing, talking all the way,

Her daughters five had their last say.

“Ma, she wants a boy, I know!”

Number 4 observed to them.

“Why? What’s wrong? It isn’t so!”

Cried the last to all of them.

Finally, they fell asleep;

Dear Ma knelt down and there she prayed;

Quietly, without a peep,

Her problem before God was laid.

Neighbors had begun to talk:

“Girls! Girls! Where will it stop?”

Pa, he could take a walk,

But she felt like her head would pop.

“Have mercy, Lord, and grant this boon,

a son! A son! May he come soon!

Not for me, or for my sake,

My neighbors, Lord, are hard to take!

Man cannot tell what God thinks best,

Until the time the vine is blest;

A Shoey boy, or surely not?

We got Estelle—just what GOD SOUGHT!

“Barefoot in Spring”

Across the fields long furrows ran

That our dear Pa plowed straight and true;

To plant the corn was Pa’s work plan

And reap a harvest as his due.

We sensed the pulse in tree and grass

That looked so bare and dead—alas!

Our hearts, they quickened more each day,

We felt a turn was close at bay.

“Lulu, do you see that tree?”

“The one whose branches make a cross?”

“It looks like leaves, and can’t be moss.”

“You both are wrong!” chimed in dear Be.

The sisters flew to brother Art,

He wasn’t quick to play his part;

“Perhaps—maybe—but it’s too soon,

wait until the next full moon.”

But Change, it came like overnight!

All woke to find a thrilling sight.

The trees that once were lifeless, brown,

Now waved bright green from trunk to crown.

Our windows opened to an air,

That Adam knew in lost Eden;

Like Paradise, with fragrance rare,

We breathed it in, again! Again!

Oh, wonderful! When morning dawned,

And off we raced through open doors;

To splash barefoot in mud or pond,

And celebrate New Life outdoors!

“Third from Nine”

When God decided, “Third from Nine”

Came to stand in our long line.

Artie was the boy Ma prayed

Would someday “soon” come to her aid.

Now at last the talk could stop

Plain View Farm had one proud Pop;

Pa could walk tall down in town,

He had his son to show around!

“Farm Life”

Farm life is no La-Te-Da!

Each day starts off in the dark!

Ma was first, then up rose Pa,

At their chores before dogs bark.

Sugar, flour, coffee too,

The store in town had them for sale;

But things we bought were precious few,

We raised our eats, from snout to tail.

Meat and produce from our land,

It came from sweat of brow and hand;

Cistern stored our cool, rich cream,

Till we poured it in the churn.

Vegetables we canned or stored,

The basement was our freezer then;

With little spent, no food bill soared,

Yet we got each vitamin.

Our Ma cooked on her wood stove,

It heated water in a cove;

She baked bread of the finest kind,

Her recipe was “Love ya!” signed.

Washing was a two day job,

We boiled clothes until they screamed;

Elastic first gave out a sob,

Then stretched to Timbuktu, it seemed.

Farm Life had its simple joys

Even when we had no boys!

In winter, frost formed on our beds,

We snuggled tight, with close-packed heads.

The hardest thing—you guessed it!

That shack outside where you go sit.

In dark and cold we made the run,

Unless White-Owl had compassion.

White-Owl, the emergency night-jar or commode under the bed.

“Saturday Bath”

Modesty had little chance,

When we did our bare-limbed dance

Across the kitchen to the tub

To snatch a fast and weekly scrub!

Baby first, then each in years,

With Ma a’checkin’ behind ears;

“Shut that door!”—you heard a cry;

Draughts were like Ma’s soap in eye.

Toward the end the stuff grew thick;

You couldn’t stir it with a stick!

In stepped Pearl at the last,

All warm effect long since past.

It’s hard to say what good it did,

But rituals are hard to rid;

What Saturday would be complete

Without our rinse from head to feet?

What other day could bear the sight

Of all our skin exposed to light?

Yet God gives grace with each sore test,

On Sunday morn we looked our BEST!

“Sunday Service”

At home and church our parents taught

The Word of God just as they ought;

With Christ as Center, God is near,

A Christless home grinds in first gear.

We seldom wondered what to do,

Our parents showed us what was due;

To Sunday School we went prepared.

No lessons done? We never dared.

Devotions in our home each day

Instilled in tender hearts a Way

To godly life and happiness

By faith and practice that will bless.

The Road that we all then begun

Is best when you have started young;

Train up a child the way to go,

And he will never end in woe.

Loving Jesus was the Aim,

It wasn’t showing-off, or game;

To honor God for all He’d done,

Upon the Cross for everyone!

And so we worked and scrubbed and dressed,

And went to church with our clothes pressed;

We never asked why we should go,

It was the Shoey way, we know.

“Off to the Academy”

A hundred miles by train or car,

The separation seemed too far;

But go we must, and loved ones part,

From Pearl first to Ruth, Lee, Art.

“We Would See Jesus!”—motto dear—

Word of Life’s firm foundation;

“We Would See Jesus”—oh, how clear!--

our aim in education.

Each class and school activity

Was centered on that noble goal;

We trained and studied hard daily

And came through disciplined in soul.

From principal to green freshman,

Word of Life was next to none;

She took each daughter and each son,

And gave them life-long direction.

Then came a sad but special day,

When each said, “Good-bye, W.A.!”

? But what’s that gleam that lasts like gold?

It’s character shaped in her mold.

A cultured mind without truth’s aim,

Produces no real, lasting gain;

Law and Grace, they taught us well,

The years have proved it, we can tell!

Word of Life Academy, a Christian high school located 100 miles from Eudora that the Shoeys sent all of their children to for a rigorous, scholastic, godly education.

“Family Portrait”

From Two came nine who all stand tall—

Fruits of parents tried and true;

Arm in arm, not one can fall,

The chain of family they grew.

Link on link, they gleam pure gold,

Spirits free and in Christ bold!

No sluggards these! They seize the day,

Giving ALL to work or play.

Pungent, sweet, and chewy too,

Their characters are all true blue;

No stuffed shirts of pomposity,

They love a laugh, whate’er it be.

Down to earth, or up to heaven,

They’re salt to meat, or just good leaven.

They stand out unique in a crowd—

Individuals, God-endowed.

Pillars of America,

Facing firm her mortal foes;

When Duty calls, no hem and haw!

Into battle each one goes.

No wasting life, no emptiness.

They have an aim for what they do;

While others wander in a mess,

They cannot miss with their Plain View.

“Fishing on Sunday”

The heart of man is dark and deep,

The things therein can make flesh creep;

How can we from God’s grace now turn?

What gain is there in works that burn?

The letter of the Law will kill,

It makes your spirit deathly ill;

Grace not Law will set us free,

It’s Christ that won our liberty.

Branded with the Hagar mark,

We labored, slaves, in sin’s deep dark;

Then one day Light shone so bright,

The blinders dropped from off our sight.

Jesus paid sin’s price complete,

Shed Blood of Christ’s mercy-seat;

Washed in His blood, from sin released,

Our new life by Christ’s death purchased.

“The Plain View Side”

What heritage will stand the test

When life turns raw and dark, perplexed?

Those times must come, of death and loss

When now you must take up your cross.

You are alone, yet not forsook,

Your Counselor stands by His Book;

The Spirit also sends a Dove

With balm and cheer straight from Above.

Those who choose the Plain View way,

Have so much, so much to say!

They’ve come through fire, water too—

ABUNDANT LIFE is now their due.

Crowns of Life grace every brow.

Overcomers, they know how!

Glean their secrets for the strife,

Which can help you all your life.

Refined like silver and like gold,

Their real value is untold;

If you like them in God abide,

You’re walking on the Plain View side.

*PLAIN VIEW FARM, written by a grandson of a pioneer farmer described in the drama, is reverently based on a true account of a Pioneer Farmer and his Family on the prairie and plains of the Midwest given to him by his mother, Pearl, eldest of the seven daughters in the Family. It is adapted to Afro-American heritage and culture through the creation of a fictional Story of William Washington Shoey, his wife Bessie, and their nine children, but the original events and significance remain unchanged.

Written by Ronald Ginther, December 21, 1992, A Grandson of Pioneer Norwegian Settlers, & Adapted For Production BY BLACK AMERICANs.

EXPLANATION:

What is PLAIN VIEW FARM the musical drama? PVF is a play set to music about how God’s love and grace can transfigure the wayward human heart. It is also about God’s love and family love, happiness won amidst hard circumstances, the value of a godly training in church and school, love of church, country, and God, and even tragedy and the loss of precious loved ones that can come unexpectedly; but most importantly the play concerns decisions of the heart, which matter for time on this earth, and eternity after this life.

Psalm 1 describes the righteous man and the ungodly man: A righteously living person, like Pa Shoey of the play, can read, believe, and rigorously practice Psalm 1, claiming all the promises of God for his life and works, and still go to the fiery lake of eternal damnation described in the book of Revelation. PVF is about a man who thought he was the righteous man described in Psalm 1 but was self-deceived; he had fallen into darkness of heart, allowing bitterness to grow up inside him over the way black Americans like himself were being treated in this country, yet he believed he was going to heaven! As for Ma, she wasn’t blind to bad racial attitudes or the color bar she sometimes encountered even in Eudora society, but she looked to God for the answer to it, and prayed for such people who put her down because of color. That kept bitterness from ever gaining a place to grow in her own heart, since you cannot hate people you pray earnestly for.

What does it take to turn such a man around, back to God’s path? In Pa Shoey’s case, he had gone so far that it took a lot—a price even he, coming to see himself as a sinning human being, could not bear to pay. Thank God, that Jesus paid the complete price on the Cross for each one of us! Each human being is THAT important to God, that God sent His only Son to die for us!

Retro Star Linking and Directory

(c) 2006, Butterfly Productions, All Rights Reserved