In Worcester far from the bay.

They lay in heaps all round the Towne,

With leaves the storm and wind knocked down.

From a shed out in St. Johns,

John Greenall watched shellfish strike the lawns.

Some would sink into the ground,

While others bounced and flew around."--Wooster doggerel

Yet Mr. Bosco Trenkle, their cane-thrashing school master with the walrus mustasche and jet-black, highly polished riding boots, drilled them like a master sergeant martinet in the army to “scan” one silly poem after another in the literature primer they were forced to study.

The school’s director, Mr. Randolf Cleffington Schwarzhuber, was convinced that poetry was an "Absolute Essential" for refining the souls of wayward boys, so that eventually they might be made productive and law-abiding citizenry.

He left discipline completely to his inferiors, its crass physicality being of no interest to him, and his subordinates drawn from the military for the most part, a military regimen was strictly, even harshly followed to enforce his system of ultra-refined and ethereal humanitarian ideals.

Country boys were lumped together with the city boys, since the theory of rehabilitation Mr. Schwarzhuber and the system followed did not recognize a distinction between the two classes, since to admit one would throw grave doubt on the theory, with questions such as: “If work and fresh air are so salutary, why have boys from the country gone so astray?” No such questions, however, were allowed airing.

Strenuous work, rigorous schooling, edifying chapel exercises, mixed with good, clean country air and enough food to keep body and soul together were supposed to reform even the most ignorant, intractable youthful character.

Beneath a large, concrete reproduction of Helen of Troy Abducted by Paris, ordered by the induction matrons, Miss Koegel, Miss Weiss, and Miss Zill to strip off all their “outer and under garments," they had to stand naked and ashamed with hands over their privates before the school physician, Doctor Grawitz, or, if he was busy, by his head nurse who inspected them for a variety of infectious and contagious diseases.

“Hey, boy, your breath is bad as a old Kentucky nag with stomach worms!” declared the quack to the gagging Clarence as he was exploring with a large metal spatula commonly used to assist mares in delivery. Not satisfied, he wedged it further down Clarence’s mouth while sticking in a probe with a seldom-washed mirror attached.

“Open wider, boy! Just as I thought, a sesquitennial bicuspid is loose and congenitally abscessed, and must come out immediately. You must have damaged or loosened it in a drunken brawl in some red-light district saloon, right? So, getting one too many hard knocks for your riotess living, you came here intendin' to have your ivories all fixed lovely and free of charge, have you? Living a life of utter dissipation and crime, you couldn’t work like an honest man and pay for it yourself, eh? You have to rob better boys than you of hard-earned public tax monies that honest men produce by the sweat of their brows!”

Clarence never did get any dental work at Wolverton in his entire six months of detention. The doctor was always too “busy.”

Clarence did what other boys did when they couldn’t stand the pain any longer from bad teeth. They used tough twine from the barn’s spools and tied the tooth that was swelling his cheek, attached the line to a door handle, and somebody else yanked as hard as he could. It usually worked, after a couple yanks.

He had other loose teeth, thanks to the blows and kicks of his uncle—but at least they hadn’t gotten infected.

Rough work shoes of the general size were dispensed to them. Names were taken from the authorities’ records that came with the inductees and sewn on a name tag that was sewn to each uniform above the single breast pocket.

Each boy was then led, after being lectured by Mr. Oskar Trenkle on the preliminary rules of the institute and what behavior was expected of him, to the dormitory room, assigned his bed, and then turned over to the dormitory house warden, Mr. Cyrus Thumann, for last instructions on when he could sleep, where he could sleep, when he must rise, where he could wash up, and whatever else was demanded.

Here also, with the “old boys” peering and making cracks at the looks of the “new boys,” they were instructed in the system of merits and demerits that governed every part of their behavior. Depending on their arrival time, they were fed or not fed.

Nothing special was done for them. If they had missed supper on late arrival, then they wouldn’t eat until breakfast, no matter how long they had gone without a meal.

Some boys fainted soon after arrival, having been in a railway car traveling for at least two days, after being given only water.

But older boys who were leaders often came and gave the new boys stolen food to gain their loyalty from the start. This way Wolverton’s secret rival gangs, the Ranchers and the Pirates, competed for “cubs” and membership and a sense of being "big cheeses" at Wolverton.

A moment later his visitor pulled up the blanket and climbed in with him. “Hey! Get--” Clarence cried out, but a hand went over his mouth. “Here’s some turkey stuffin', stupid!” the intruder hissed in his ear. “Don’t you make any noise or house warden will stick us both in the caboose! Then I’ll beat you up good!”

Clarence smelled something wonderful then--it was food--real Turkey and the stuffing in a rolled up table napkin, fresh out of Swarzhuber's kitchen!

A second napkin held bread and bacon strips, fresh from the school's kitchen.

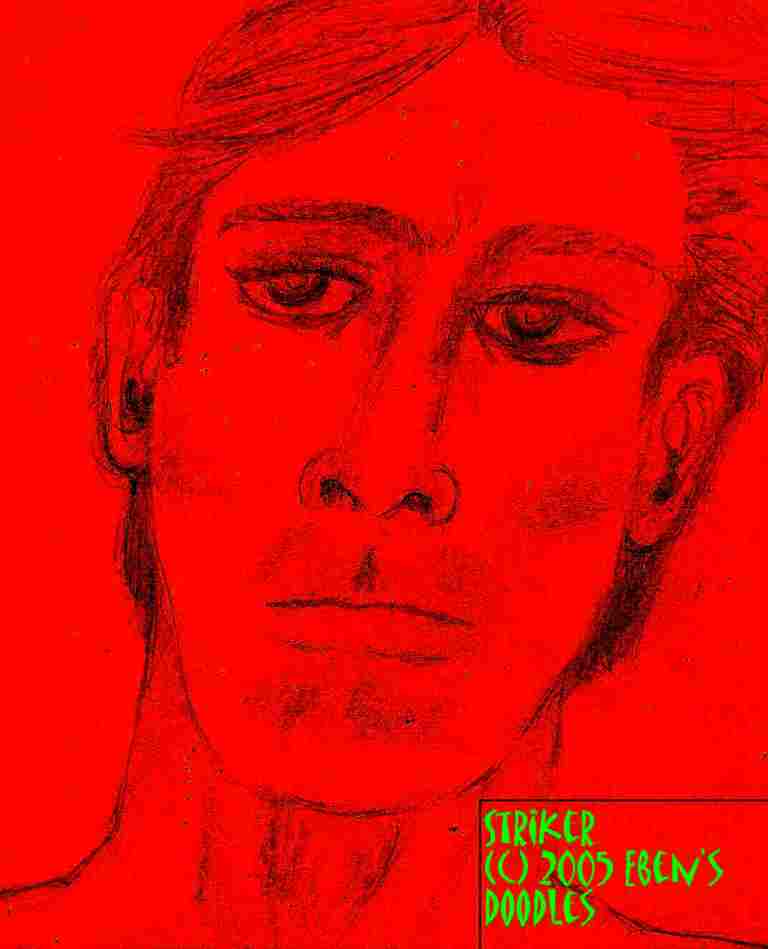

The intruder with the portable chuck wagon was just as quick to leave as he had come. “My name’s Striker-—remember that! Striker! I head up the Pirates, which is the ruling gang here! They call me Striker ‘cuz I always hit the most home-runs on my team, and even Schwarzhuber doesn’t dare harpsichord any of my boys! You’ll be glad of that when you find out what he does to the others! I’ll contact you again tomorrow night the same way! For you’ll probably mess up the first day and then you won’t get fed! That’s how they break your spirit!”

He was hustled out of bed in the chill, early morning, wakened by the thunder of bare feet pounding the floor by the dozens. He had slept in his clothes, so he didn’t need to dress. He had no idea where he was at first, it was all so strange. But boys were pushing him along as he tried to make sense of it all. He stood in the washroom, wondering what to do.

“Wash up, you dirty Pirate!” a boy yelled at him, throwing Clarence a towel and wash rag. Clarence recognized the voice, then headed to the sinks, to find one that was open between the jostling boys all lined up. When a spot opened, he got it and went to work. He was wretchedly filthy from having no baths for longer than he could remember. Baths were not permitted that day, nor the next.

Only once a week, Saturday morning, was the luxury of soap and hot water permitted, he was told by a boy on his right.

Holding a wooden tray and cup thrust at him by a serving boy, Because the cooks were mostly Civil War veterans from the south, Clarence was given a wallop of southern-style hominy grits and a piece of bacon and a cup of coffee when his turn came at the head of the line.

The cooks seem to be favoring some boys over the others, with eggs and extra grits and bacon, but he had no time to see why that was so. Hurried to a place at one of the long, bare wooden tables, he ate ravenously, and was still very hungry when he finished.

Next came chapel service. School wardens read out a roll call first, then they were dismissed from the mess hall to assemble in the baronial, chandelier-lit chapel. The school chaplain led the service with a selection from Thoreau’s essay on “Civil Disobedience.”

They all had to stand to attention during the whole reading.

The assembly was called to stand to attention as the school director departed, and chapel was dismissed, with the boys marching in file to the first class of the day.

It took the entire half hour to get through the line and be served and eat.

Clarence no sooner bit into the sandwich then his eyes looked startled, then compressed to slits as he continued munching what he really wanted to spit out. Next they all had to march up in single file and go to the dairy and cattle barns for the assigning of work duties. The work warden’s assistants, Baranowski, Aumeier, Hofmann, and Eichmann took each work assignment and chose which boys were to tackle each task. Sometimes an over-tired assistant took an assistant from among the boys. Clarence watched Striker called out from the ranks to stand with one of the assistants who was forming up a troop of boys.

“What are you, Pirate or Rancher?” the same boy wanted to know.

“Pirate, I guess,” Clarence shrugged.

The Rancher boy looked disappointed and glanced closer at him. “Aw, you don’t look Striker’s type! He’s mighty particular! Where are you from anyway?”

From habit Clarence would have lied, but this time he thought he was safe enough. “Alaska Territory.”

“Really?” the boy said, seeming interested. “Where exactly? And how come you came here to this dump of a reform school? What’d you do?

Clarence was given no time to reply, as they were split up into various work teams. Though the last to be called, he ended up in one over which Striker and the work warden’s assistant presided.

The field was well-guarded by a high fence, however, and wardens stood watch as the boys played. No one was permitted to leave during the hour.

The Pirates and Ranchers had their chance to compete, and it was a bitter struggle. Clarence found himself pushed to the end of the Pirate bench, when it was found out he didn’t know the game well enough to help their chances. The game wasn’t over when the bell sounded, and the boys dropped their equipment in disgust. Marched back to the schoolrooms, they were instructed again in Shop and Mechanics.

This was the most popular course, Clarence found.

He too liked it, the smell of the wood shavings bringing back memories, and he liked handling the wood, saws, and equipment. An assistant soon took notice and motioned to him.

Clarence stood amazed. He had no idea he might make so high an honor, after not even a full day at Wolverton.

Striker came by to look at Clarence’s project, a small table that resembled one the miner’s used. Clarence planned to add a couple chairs to it as well. He could hardly keep his attention on the chair, however, since this was his best chance so far to get a good look at his benefactor.

Clarence’s eyes widened. “How—“

Striker laughed. “I’ve already gone over your records, so don’t think you can sucker me and get away with it. You’re under probation, an investigation is still going on, and they’re still trying to decide what to do with trash like you after the report came to Frisco police you’re a chief arson suspect for when a whole town burned down in Alaska-—now what was its name?”

Clarence’s mouth fell open. Though no one else could overhear this, the work room being so noisy, he went so pale that Striker laughed and slapped his shoulder. “Don’t let it bother you, little brother! Everyone slips now and then. We’ll take good care of our little arsonist. Just do what we say, and you’ll not wash out. We Pirates are the worst of the worst! That’s why we make good Pirates! We meet when I tell you tonight. Thumann will be drinking tonight as usual…so you better make it to the meeting. It’s your initiation.”

A chill came over Clarence as he realized his past clung to him like iron chains and wouldn’t let him go. He was trapped! Would they investigate and find out all the rest about him?

So they were going to initiate him into the Pirates gang! Didn’t he have any choice? What did that mean? Was he going to have to fight with the Ranchers, or go on escapades with the Pirates and maybe get caught and whipped for it? Wasn’t he only going to get himself in more trouble?

His head whirling with questions, he couldn’t keep his mind on his work, and the result soon showed. The assistant came by, frowned, and passed by after commenting, “You’re being pretty careless how you’re doing that table, boy! Sharpen up! Pay attention! We don’t waste good wood here! You’re asking for a demerit.”

Clarence’s face flushed red as he realized he had cut the board wrong, going way off the line he had marked with a red pencil. Could he save the board by making the table smaller?

“I don’t wanna go there,” he tried to tell her, but she always replied, “I can’t see you starvin’ here like this and running raggedly in the street like you wuz an orphan, so you gotta go to a better place!”

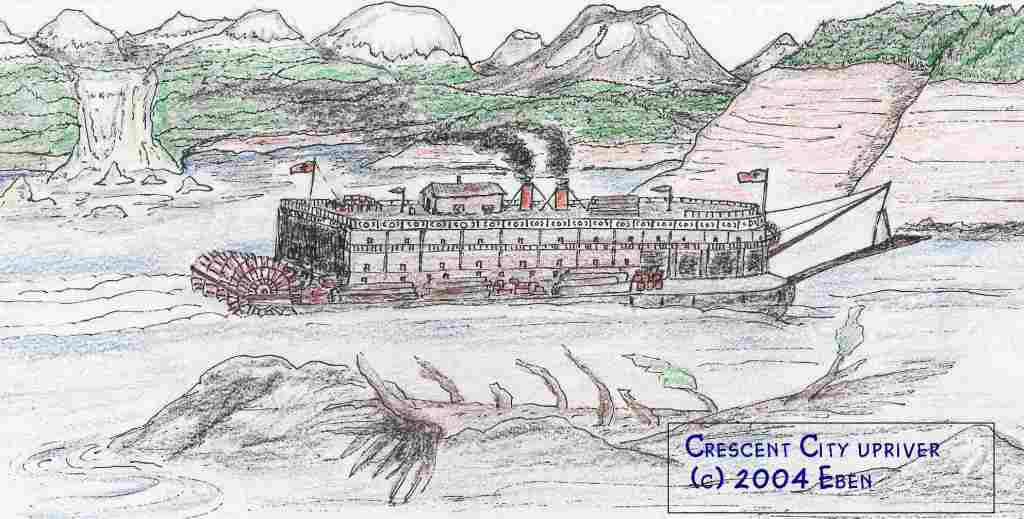

What could he do? He thought of running away, but where would he go? After his mother scraped up the money for the fare somehow, he let himself be put on the riverboat that took him up the coast to a river inlet, then to the town where his uncle bought supplies, the last point in the river where the boats could dock.

“’Bout time you got here, boy! I been in town for two days expecting ya!”

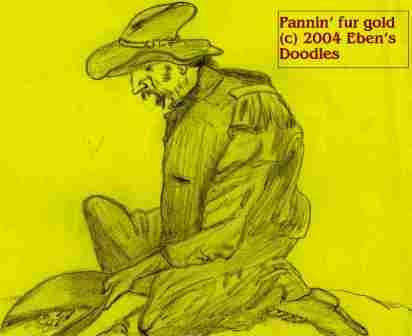

The old man peered closer at him. “Yeah, you do bear some resemblance to my sister. Poor woman, she haint no sense, married a no-good who left her, then had you to raise! Well, maybe I ken git some good outta you!”

Clarence nodded, figuring it had to be his Uncle Arthur. His guardian looked laughably pathetic in Clarence’s eyes. What possible good could this old man do him? He hadn’t money to go back on the boat, so he had no choice, he thought, but to follow his uncle to whatever hell was in store for him.

By the remarks directed to his uncle by passers-by and the usual riff-raff of tramps and unemployable men and idle boys that hung about riverboat landings, Clarence soon was surprised to find that his uncle went not known by “Arthur” but “Sourdough,” or “Scottie,” even “Sourdough Scottie.” His mother had only make a few mentions of him, always using the name Arthur. “Your Uncle Arthur will take keer of you, son,” she said on parting. “Just remember that name, Uncle Arthur—“ her last words naming her own maiden name (which the boy didn’t know or recall) were cut off by a riverboat horn blast, as they parted. But now he was Sourdough Scottie’s boy!

His uncle was anxious to get back to his place outside town, so they didn’t take long as his uncle led Clarence between a row of saloons named for local mines—The Last Chance, The Golden Nugget, The Silver Slipper, the Comstock, The El Dorado, The Mother Lode, the Jack Pot, Lady Luck, and the Semiramis Opera House Saloon. Squeezed between or built alongside or at the back of main street were stables, blacksmiths, a Hudson’s Bay store, an embalmer’s funeral parlor, and the most important place to his uncle, the essayer’s office that weighed and paid for gold. Despite the names, the town was really based on logging and trapping, for the gold rush had been short-lived, lasting only a few months before the initial strike petered out.

Hustled out of town by his uncle, Clarence looked back over his shoulder a number of times, regretting every step that took him away from it. On the way up to it they had to cross a railroad trestle, and Clarence thought his life was over the first time he crossed it. Through the tears in his blurred eyes, he hardly saw it. He never learned the name of the river that flowed below it in the rocky gorge.

It was the long, wooden, trough-like contraption running down the mountainside, that carried spring water like a creek and was used to wash the ore and separate the dirt and gravel from the gold dust.

Clarence’s job was, to begin with, hauling the ore out of the mine and then dumping it into a big bucket, which every now and then his uncle would upend into the sluice. Every phase of the operation, from digging the ore, hauling it out of the mine, and sluicing it was gruelling work, Clarence soon found.

His uncle had done it for years, and the unrewarding labor had soured him. He was always cursing the damp, the poorness of the vein, the weather, the mountain, his bad luck, the town’s money-grubbing merchants, anything he thought hindered his success and striking real pay dirt. In Clarence, his inept, citified nephew, he soon found a new basis for complaint. He had to pay for his room and board even when he was finding not even one speck of gold in the sluice. He soon resented the boy’s appetite and poor working habits.

“You’re nuthin’ but a pretty faced, soft city boy!” his uncle railed at him. “I tol’ my sis I need a real good worker, but what I git is somebody like you, a bloomin’ little sissy who can’t swing a pickax or even fry a strip of bakkey right! I gotta do everything for you! Didn’t your ma teach you anything a man otta know? It’s a mistake I ever told your ma I would take ya offa her if you wuz ever gittin’ too big for your britches!”

Cursing Clarence, the uncle soon resorted to knocking him about the cabin after more days of “bad luck” at the Golden Nugget.. Part of it collapsed, nearly catching the both of them in a ton of fallen rock and dirt, and this the uncle blamed on Clarence. “You must have knocked one of the support timbers loose somehow!” he shouted at the boy. “You could have kilt me dead before I make my really big strike! Take this! Take this!”

Booting the boy, slapping and punching him, the uncle let Clarence know he wouldn’t get away with such careless behavior. The first time it happened, Clarence wanted more than anything to run away, but the cold was intense, the winter snows were piling up many feet deep. His uncle’s narrow, dark-beaded eyes grew crafty looking at the boy crouched in a corner of the cabin where he had retreated after the beating. “I know what you’re thinking, boy! But you can’t git fur! The wolves and polecats will et ya! Haw haw haw! Nope, you won’t get fifty feet from this cabin, and I’ll find your gnawed bones when the ice thaws come spring!”

Clarence, his rage burning like a torch inside him, gazed out the one window of the shack and knew he couldn’t escape in winter, somehow he had to take the beating and look for another time and way of escape. He hated his uncle in the morning, noon, and evening. When he awoke the next morning, he hated his uncle even more, if that was possible.

“You’re comin’ with me, boy!” he announced one day. “I’m not leavin’ ya here here to steal me blind, and then burn the place down—ungrateful wretch that you are, after all I done fur ya!”

Clarence had heard it already a hundred times, usually accompanied by kicks and body blows from his uncle’s fists. Yet his ears burned. He never could get used to the continual accusations. He knew better than to object and defend himself, for then the old tormentor would get all the more angry at him, and beat him mercilessly until he was near to blacking out.

So—-at the next day dawned-—they set out into the snowy waste. It was hard going even in big snowshoes strapped to their feet.

“You go ‘head of me!” his uncle shouted at him. “That way I’ll see you fall through—if there be a hole in this here track under the snow! Why should I have to put up with ya, anyway? Good riddance, if you do fall through!”

Trembling with anger, Clarence went ahead as the test animal for his uncle. They reached the other side safely and then with a strong wind blowing on their backs continued down the side of a deep, narrow valley that plunged through the forested slopes of mountains and big hills and spread out into the distance toward an inlet. As they descended into the valley, a stream broke from the snows and accompanied them, growing into a river before too long that they couldn’t safely cross without being swept down. On the steep slopes around the river and even on the valley floor the forest had been cut, with the trunks left in place until the spring thaw.

Even with the gold rush and the hasty erection of the saloons and shops, the town still bore signs of the poverty-stricken shantyville sprung up along the old Skid Road, where the first cut logs were rolled to the water for the river to transport down to the coast where ships hauled them aboard.. Before the mills were built, the logs were shipped out as they were cut and only a few men made money, but then with the mills a real lumbering business increased the town’s size and money-making, and tradesmen set up businesses, and even some respectability arrived with a church and a false-fronted two-story frame “opera house” that doubled as a saloon. As the mills expanded and more money passed hands in town, saloons did better business with the sawmill workers than they had during the brief gold rush days. Since the few mines played out, only a handful of miners lingered to pan the streams and the river. Thanks to the logging, the riverboat made more frequent trips, carrying gamblers and ladies of loose morals and even some avid missionaries with the Gospel.

Testing it, the assayer found much to be desired in the ore, it seemed, for he shook his head and went to hand the gold back to the owner, which riled up his uncle to the point of cursing the assayer to his face and threatening to take his business elsewhere.

Twice, then three times, the gold was re-tested and weighed, until finally his uncle was satisfied he wasn’t being cheated. The assayer then laid out a five dollar gold piece, and his uncle snatched it with a stream of profanity and some tobacco juice and stomped out, slamming the door.

With money to spend, his uncle was so preoccupied with his own pleasures at his favorite watering hole, the Golden Nugget, that Clarence realized he was free to roam around, and he slipped away to the much more interesting steamer’s wharf. There he tried to blend in and he hung around until he got up the nerve to ask about the passage fare to his hometown. The captain laughed as the boy’s face paled at the sum.

“We can charge folks anything these days and still git it, they be so anxious to come out here to strike it rich in the mills and the mines! What a crock! I seen most such leave here in ‘bout six months or a year with nuthin’ but the shirt on their backs, and lookin’ old and broken down, fit only for the po’house! Haw haw haw! This here territory separates the men from the boys—I always sez!”

Cuffed and given a big push, Clarence sprawled face-down in the mud, and the men and boys all around laughed. Just when he got up he felt a terrific blow on the back of his neck. “Aimin’ to run away, huh? Did I say you could come down here? I’ll teach ya!”

His uncle kicked and booted Clarence back into the mud each time he tried to get up and away. They were soon a laughing-stock of the whole town, as everyone poured out of the saloons to watch the comedy taking place. Finally, his uncle tired of it, and went into a saloon, leaving Clarence hurting and broken-hearted in the mud and gathering gloom.

The next day his uncle roused enough from his drunken binge to buy supplies at the Hudson Bay store and, load them on Clarence, so that they could return to the mountain. Passers-by laughed as the old man and his nephew passed. “That’s some mule you got helping you!” they joked. “Cheap, eh? You always had a good eye for bargains, right? He’s doin’ better than a dog team—that mule of yours!”

Clarence’s ears stung as he heard their remarks and laughs at his expense, while he struggled to carry the sacks of flour, bacon, and other provisions against the strong wind that ripped down into the valley town from the mountains.

How he reached the trestle, Clarence had no idea for the savage wind that blew down into the valley was like a wall he had to push against the whole way up to the crest. Finishing off the bottle of whiskey his uncle was always refreshing himself with, he forgot to send Clarence on ahead. Halfway across the span Clarence thought it was now or never. He struggled free of the ropes that tied the provisions to his back, and then, like a phantom, rushed at his uncle’s back, his arms extended and hands ready to give a violent push.

The scream of his drunken uncle and the tinkle of a shattering bottle along with a something heavy landing with a couple sounds of something hitting then bouncing and hitting once again—-did he hear really it?—or did he imagine there was no sound at all, just the sound of his own steps in the snow and his own breathing fast and furious both before and after his brief dash.

Lying back on the snow, he heard a voice shouting, “Go to hell! Damn you! Damn you! Go to hell!”

It took him a few minutes to realize it was himself doing all the crazy hollering, when he knew there was nobody to hear him. Was he out of his mind? He rose up, feeling sick and light-headed but also thrilled with glorious, new found freedom. He had done it! At last! At last he was free of the old monster! It seemed anything good might happen now. Life was again full of endless possibilities for him.

The chill of the gathering dark quickly sobered him. He realized he needed to seek shelter, as the wolves drawn by his uncle’s body would be looking for anyone else lying dead or wandering in the snows of the mountain. Loading up the provisions on his back, he hurried over the remaining half of the trestle and off toward the cabin. Forgetting the whole incident for the moment, he burst into the cabin, and then dropped the provisions on the floor. He spun around, realizing for the first time it was his own, to do with as he dang pleased!

He set to work, building a fire in the cook stove, and then made the biggest batch of pancakes he could mix up in the biggest pan his uncle had, and after frying them, he added bacon, and then poured syrup over the whole pile. Feasting, he ate until he couldn’t eat anymore. Then before he went to his own bed, he found himself tearing his uncle’s bed out of the cabin and sending it down the mountainside. He also broke into his uncle’s liquor cabinet, but by this time he hated the drinking so much he smashed the bottles outside on a big rock.

Only then, exhausted and over-fed, did he drop on his bed. Rising early in the morning, he relit the stove and warmed up some pancakes. He thought hard. He realized he had to get out of the cabin before somebody came by and began asking questions. He had to find something valuable to sell for the ticket he needed to escape the town. Mining equipment was costly stuff, he knew. He took some of his uncle’s gear, all he could carry, and set off for the trestle.

It finally dawned on him as he gazed at the spot. “I done a man—my mother’s brother is dead because of me. His carcass is lyin’ down there somewhere on the rocks.”

The realization coldly brought him to his senses. His head whirled with panicky questions. “What happens to me if someone finds out what I done? What if they start askin’ questions where he be? What’ll I say?”

His courage fled completely away. He realized how young he was, he had utterly no experience how to handle all the adults who would be coming at him. That stopped him in his tracks. He knew he couldn’t continue to town, not knowing what to do or say to account for his going there alone, with his uncle’s belongings to sell. The town, in fact, was the worst place he could turn at that moment. The town had no sheriff. They’d have him hung in five minutes out back of one of the saloons!

A plan slowly came to mind. Would it work? He had no other plan. It had to work! He knew he had to work the mine, and then collect what gold he could find from the sluice, and use that to sell and buy his way to freedom and escape. That way he wouldn’t be putting himself in so much suspicion.

Kutch the essayist, unlike his uncle’s saloon-keeper friends and drinking buddies, wouldn’t ask questions if he had gold to sell, would he? He had to wager he wouldn’t. If anyone asked, he’d say his uncle sent him to town with the dust to sell for extra supplies he needed.. Trying to sell his uncle’s things was now, to his mind, the most stupid thing he could have attempted.

No, he had to get some gold out of the old mine! And get it as soon as possible, before anyone missed the old man and thought to pay a call.

Was he every going to get enough? The tiny flakes and grains eluded him, despite the loads of ore he dug out of the shaft’s vein and hauled to the sluice. Fortunately, the sluice was fed by a warm springs that never quit running, even in the coldest freeze.

It ran clear for several hundred feet before it froze up down the mountainside. That was how his uncle was able to keep working the whole winter, and how he had made it so long on so poor a vein.

At last, flake by flake, grain by grain, the needed amount was accumulated and Clarence took the bag, got out his snowshoes, and set out for town early one morning after emptying the glowing embers from the cook stove into the loaded wood box. Leaving the door wide open he left everything without a backward look.

He also brought matches with him, wrapped in grease paper to keep them dry, and at the edge of town where the big mills stood, he paused behind one and lit his matches in a barrel containing shavings, wood scraps, sawdust and oily rags.

Then he ran for it in the dirty, churned up snow of the road, slowing for a walk when he realized he might draw attention, as he made his way through the town to the steamer dock.

There it was like a shining angel to his eyes! His luck stood good! All he need do is sell his gold, take the money and buy his ticket to freedom.

In the meantime, in case there was anyone who saw him, attention would be diverted by the fire at the mill. Just as he thought, as soon as his gold was sold, and the money was safe in his pock

et, Clarence saw he had gotten his money just in time, for the first sign of anything wrong was men running toward the mills with everything they could grab to fight the fire.

A wind was blowing hard, however, at the back of the fire. It swept the fire into the mills and continued sweeping the fire into the town with a burning wind and a rain of coals and brimstone-like cinders and firebrands.

The wind grew more savage as the moments passed, for it was a well-known one sweeping down from the mountain through the deep cleft cut by the river. Like a billows, the wind fanned the flames to greater and greater ferocity.

The firefighters panicked and began running back from a twenty foot wall of flame that was sweeping from the mills, which were lost anyway by this time.</h3>

The captain finally ran up to the steamer and boarded. “We’re gittin’ outa here! Town’s goin’ to burn down around our ears in five more minutes! We’re gittin’ underway!”

His shouts brought the engineer to furious efforts to pump up the flames beneath the boiler, and the wall of fire was close and moving fast enough to send the townspeople running, carrying what possessions they could from their houses and shops. Saloons emptied last, as the loggers took their last drinks for the road, and then looted the premises.

The captain took Clarence’s money without counting it. “Git on, boy!” he shouted, and Clarence needed no more prodding. He leaped across the gangplank. A whole crowd followed, but the captain and his assistants had to beat off most of them with wood planks after withdrawing the gangplank. Too many passengers and they would all sink to the bottom of the river!

In all the excitement and terror and turmoil, nobody had recognized Clarence, he thought. Nobody asked him where his uncle was. Nobody could care less about one man in the midst of the fire destroying the whole town. It had worked! His plan worked! Better than he had ever imagined!

As the steamer continued swiftly down the river and put the burning town behind it, Clarence would relish his freedom, he did so. Only when men started noticing him traveling alone, did he get any questions.

“Hey, I seen you before, boy|! What happened to your uncle, boy? Didn’t old Sourdough make it out? How come you did?”

Clarence had to think fast to answer with any believable. “It’s terrible what happened, sir! I was waiting for him as usual at the Golden Nugget, and he was still there when the roof fell in. I tried to go in and git him out, but the flames were too bad—I couldn’t—“

Only by the time they reached Clarence’s hometown of Juneau, he found he had real trouble on his hands. Now the skipper and the crew and passengers could turn their full attention to Clarence and the whereabouts of his uncle. The captain in particular eyed him with deep suspicion. He had pocketed the boy’s money. He now held it out.

“Where you git this much money, boy? Did you uncle give it to you? How could he, if he was lying back in the Golden Nugget when the roof came down him?”

Questions like that were raining thick on Clarence’s head as they neared the dock and true escape to freedom.

This here boy is his nephew! His only kin, I reckon, as he never married and he only got that one sister of his, he told me. Why, he could have inherited his uncle’s million dollars! Fat chance of that now, with the town and all the mills burned to the ground! That land is worthless now1 Worthless! You couldn’t give the deeds away—if they didn’t get burnt up in Kutch’s bank vault. Who’d want to build in that death trap of a valley again? The place is jinxed, I tell ya! Jinxed!”

He didn’t dare linger, because he was afraid he would be arrested any moment if he stayed in town where many people knew him. Half-dead at times with hunger, he continued down the coast, catching rides with fishermen, or with miners returning to civilization who needed someone to help oar their boats. Bit by bit, he made it a thousand miles south to Oregon, then on to California. All that wretched and haunted journey, he had time to think about what the men aboard the steamer had said.

His uncle had been filthy rich! He could have lived like a king! He, Clarence, was his only surviving nephew, the heir to a million dollars! But now it was all ashes! Ashes!

The house warden was strict: no talking in the dormitory quarters. No groups. No passing of notes or anything else. Any infraction past bedtime earned a double demerit.

When the bell sounded for each boy to finish his “nightly meditation” over a printed saying of David Thoreau or Ralph Waldo Emerson handed him, Clarence climbed exhausted in under his blanket. He couldn’t possibly concentrate on it, and like the other boys he scrapped it. Some more fastidious boys even collected the printings of Emerson and Thoreau for toilet paper, since the type provided by the Institute was greatly inferior in quality.

Lights went out at the stroke of 7 o’clock when an alarm-like bell sounded.

Clarence waited in his bed, hoping Striker wouldn’t remember the meeting, or it had been called off due to the incident of the missing boy.

Hours passed and Clarence dropped asleep. He was rudely shaken awake. A crouching, blanketed form in the dark grabbed his arm and pulled at him.

Groggily, he followed, pulling a blanket over himself to serve as a night robe.

Striker kept going, using a key to get them out.

Quickly, their leader shepherded them down the hall, past various concrete statuary left over from the mansion’s heyday when Ronimous Wolverton the millionaire railway tycoon spent his last days before his suicide there ruling an empire of rail lines that nearly toppled the Eastern banking syndicate’ control of California.

Clarence was only dimly aware of the giant shapes that decorated the cavernous concrete-shell hallways they walked down in the dark, with chandeliers and corridors opening out of the hall leading to mazes of other rooms and apartments. Finally, Striker used a key and opened up a room and they all went in. He locked the door and then lit a lamp and faced them.

First thing Striker did after they all locked arms at the elbow was hold up a dead rat dangling from a string on a stick. “All recite the sacred creed of our immortal brotherhood,” he ordered. With Clarence listening, they all repeated the most chilling ditty he had yet heard.

Figure you’re dead for what ya said!

Be a Pirate but do a clam,

Or in your mouth we’ll grave dirt cram!”

“Okay, new business! Pirates, name yourselves!”

Each Pirate named himself with a Pirate name. Then came Clarence, but no one expected his, and Striker called him up to his feet and took his blanket away as the Pirates eyed him with stony, grim expressions as he stood there exposed and shivering in none too clean underwear.

“Glorious Pirate Brotherhood, we’ve got a new candidate to initiate. You see him! If he passes, he becomes a fellow Pirate. What name shall we give him? Any suggestions?”

Several names were thrown out by the boys. “Naw,” said Striker. “You can do better.”

He went and peered closely at Clarence, then seemed to think of something that amused him. “This one burns a whole town down, so why not call him after that guy who burned down the Temple of Diana. Anyone remember his name?”

Nobody did, so Striker tried again. I still can’t recall what town it was he burned down—maybe he can tell us!”

Every eye fixed admiringly on Clarence, who hated being the object of their intense scrutiny and felt like sinking into the floor. What if he should lie? Would they detect it?

“Yeah, I like that,” said Striker. “So you’re Gypsy! Yeas or nays?”

Yeas had it, and Clarence was now “Gypsy.”

“Next item of business, “ Striker went on, “is his initiation. What’ll it be?”

“Have him crawl through the manure in the drains, then roll in the straw, and we all get to beat on him!” was one horrible suggestion Clarence heard. The others sounded not much better. “Naw,” said Striker. “That’s letting him off too easy. He has to think he’s really dying at least, not just getting beat and made to stink like a skunk!”

Striker turned away as if considering his own thoughts. He paced back and forth, then suddenly stopped.

“I got it! But first he has to be tied up so he can’t get away and spoil it for all of us."

Clarence was breathing hard now, wondering if he had to fight his way out of there like a wolverine would to save himself. The boys gave him no opportunity as they leaped on him and did what Striker directed. None of them wanted to get near the manure, so they gladly took Striker's idea, waterboarding.

Tied to a board so that he couldn’t get away, they led him out of the room and out of the mansion, and reached the barns. There he was tied to a thick rope, and several times he was dunked into a watering tank for the cattle and kept under water as he struggled in vain to get free. Nearly drowned, he was finally drawn up and untied.

Clarence collapsed on the ground, spitting out water and bits of straw and fit to kill.

Suddenly, he felt the boys gather around him, patting and slapping him and welcoming him like a dear brother and comrade into their midst. It was so totally opposite to their former cruelty he was stunned and didn’t know how to respond. He had wanted to kill them for what they had just done, but how could he do it now? His preferred weapon was a Chinaman’s curved little knife with a dragon carved on the hilt, and the cops had snatched that away the first time he was taken into custody. Then they all seemed to be enthusiastic about his becoming a Pirate and how he had taken the initiation. He had never felt so warm a treatment, and he wanted to believe it as he looked in the eyes of each Pirate.

“You did real great, Gypsy, just like a pirate!" each boy said in his fashion. “You didn’t cry or beg for mercy or even turn religious and start praying for help from God to save you!”

That was true to the mark, Clarence was never a kind to do that, no matter how hard it had gotten for him up at his uncle’s cabin at the old mine.

Meeting adjourned, they crept back to their beds, the house warden still sleeping off his binge.

Striker passed him when they were going to chapel, whispering, “They’re going to send you to the caboose just to break you in! So don’t be surprised.”

The room stank of urine and stale air and mice that had crept in and died in corners and cracks.

Clarence sat down on the mattress, only to discover it was crawling with bedbugs. He quickly found a corner as far from the mattress as he could. Never had he felt so miserable, spending hour after hour, without food in such confinement. By the next morning he was sleepless and frantic to get out.

It was a suffocating experience, and he felt he couldn’t breathe in such a hole. Another boy was led in as he was let out. He heard the boy start yelling for mercy almost immediately for someone to let him out.

Feeling weak and sick, Clarence could not think of any word of response. He could hardly wait to get free of the guard and back to his bed to lie down. Anything was welcome after the detention in the caboose!

Though he tried that day and the next to do everything right, he still received more demerits. They earned him his first caning. But it wasn’t a cane the house warden or his assistant Cronwitz used, it was a long, thick, rudder-like paddle that shot pain through his whole body like hot, crackling electricity. After several blows he was trembling where he stood leaning over a table as commanded. He couldn’t sit after he received the six blows his demerits earned him.

Missing meals was the worst punishment, he soon found. He had to do the same amount of school work and outside tasks, though he hadn’t the energy and strength. If they continued to do this to him, he thought, he was going to have to run away if he could, or collapse.

One of the assistants, Loritz, took over Clarence’s case who was adept at handling the stronger willed boys. Only one boy, Sriker, had successfully opposed him with his much greater intelligence.

This man liked to wrap a wet towel around a boy’s neck and squeeze until the boy thought his eyes would pop out. He did this to Clarence. Clarence passed out, and when water was thrown in his face, it was Striker that Clarence saw.

“I admire your standing up to them, but you’re only making it harder for yourself! They want you to beg them to quit hurting you, so they can quit bothering with you But you’re making them be all the harder since you won’t back down. They know they will look bad if they can’t have it look at least like they are in charge here. So say something anyway! It doesn’t matter what it is—just let them know you know they are your superiors. If you just keep silent, they will think they have to work on you all the harder to break you and make you accept their authority. And one of them loves doing it! He’ll enjoy killing you like a chicken with its neck wrung! That is what he used to do, work at a chicken factory!”

Loritz also punished the serving boys caught stealing fruit pies in the kitchen, desserts meant for the table of the director. “No, honest, we didn’t steal any [obscenity] pies!” the half-witted Rancher boys cried when called out and confronted, though they still had traces of blueberry and blackberry and apple pie still smeared on their unwashed faces. These boys too, though so slow-witted they couldn’t possibly think of excuses or a way to pass the blame, were strangled to an inch of their lives and bore the distinctive collar of red and black for days afterwards.

The demerits and punishments did not stop, and Clarence was increasingly desperate to either escape or kill himself.

Nobody was allowed to talk about it openly. The rest of the day went according to schedule. Clarence was sent again to Loritz the strangler, and he hoped that time was his last, and he wouldn’t wake up.

Then the director made a surprise visit to the schoolrooms with his wife, her first appearance among them since her recent arrival from Philadelphia. Cowlike eyes, large in girth, dressed in dark, heavily ruffled silk, she looked an ample counterpart to her husband who walked up and down the silent rows of Clarence’s class as the teacher of the beginning year boys sat waiting. It was the first time Clarence had seen the director so close. A very big, massive-framed man, his hands huge and man-killing as Thor’s hammer, which would explain the thunderous, half-smashed harpsichording that issued periodically from his quarters—he could easily pound any lesser instrument of flesh and bone into submission to his will, Striker’s clever ways and experience notwithstanding.

To emphasize his point, he let his fist swing against the blackboard. The blow sent chalk dust spurting from all the cracks and rattled the whole sheet of slate almost to the point of shattering it.

The director eyed the whole group. Meanwhile, the teacher glared at the boys, as one or two looked as if they might speak up. But the moment passed, and no one dared complain to the director in the presence of the teacher who would severely punish them.

Smiling broadly, the director turned to the teacher, his tremendous slap across the shoulder blades nearly collapsing the man and fracturing his collar bone. “Carry on, you are doing an outstanding job, Woonsocket,” he remarked cheerily, sailing ponderously out of the room with his wife.

An inspector from the state commission for review of the state’s reform schools also paid a visit. The boys were served all the fruit pie they could eat at lunch, their work duties in the barns and fields drastically curtailed, an extra hour at sports was awarded so they could play an entire game for the enjoyment of the inspecting official, and a hastily assembled and rehearsed boys choir sang for him and the director and his wife at a special reception and ball attended only by the highest staff of the institute.

Everything returned to as it had been before the official’s visit, however. If anything, the treatment grew more harsh when he was gone, along with the departure of the director’s wife back to Philadelphia Clarence continued to receive demerits and punishments.

Listening, now Clarence knew what had been only hinted to him previously. It horrified him to think he too might be selected for a “harpsichording” session. What was it that the director did to his victims?

One boy with blond hair and good facial features had come from such an private meeting with the director during Clarence’s time at Wolverton. For days the boy looked dazed and had difficulty even answering his name right at roll call, either because he couldn’t hear or his brains were too muddled. Then one day he was called out and sent to another farm school that had a mental ward. Clarence never dared ask him what had happened, and only chance remarks reached his ears.

The other remark was even more chilling. “He says to us afterwards when he come from there, old Schwarzhuber tied him nekkid to the lid of that harpsichord and then played four hours straight! After that, he lifted him off and with one hand threw him across the room onto a couch! Then he drug him to the bathroom, rammed his head into some towels to ketch the sound, then paddled him until he fainted. He did some other things too like that, before it was back on the top of that harpsichord for more music!”

Clarence didn’t have to think about Striker’s offer. “Yeah, I’ll do anything you say, Striker!”

“Good!” said Striker. “I’ll get you details of my plan later. I am making a few necessary arrangements first so we can make a clean break.”

Striker slipped away like a phantom, just as stealthily as he had come. No one ever blew the alarm about him among the staff. Striker never was awarded a demerit. Apparently, to Clarence’s thinking, Striker had somehow struck a deal with the staff to leave him alone. What did Striker do, or what did the staff fear Striker might do if they didn’t? It was Striker’s big secret, and he wasn’t confiding in Clarence.

Their planned break-out couldn’t come soon enough, Clarence felt. He couldn’t stand the thought of spending another day at Wolverton. What if the mad harpsichordist who ran it chose him to spend the night? What could he do to defend himself? Nothing!

Striker had all the keys necessary and the route mapped out perfectly. They made it clean out of the mansion without anyone spotting them. Miles down the road, it was still dark enough for them to slip off the road unseen into the bushes should anyone come looking for them. They passed Ronimous Wolverton’s pride and joy, his concrete fairyland of giant replicas of Stone Henge, the Great Pyramid at Giza, the Taj Mahal, and a Pagoda. Overgrown with thorn bushes and sage brush since the tycoon went bankrupt when Eastern bankers called in his notes prematurely and shotgunned himself in the mansion’s library, the concrete monsters stood all the more impressive in their utter desolation and ruin.

Once their owner envisioned trains full of well-heeled excursionists coming out from the big cities and towns all over California to see his marvels of ancient architecture—the Wonders of the World, of which seven he had made pains to recreate along with others he admired from his world travels.

Taking rest in one of Wolverton’s marvels, Clarence leaned against a giant replica of Ramses, the pharaoh whom Moses the deliverer of the Hebrew slaves had confronted in the Bible, and he had no idea what the statue signified, or that it meant anything at all. Striker, being better educated, knew somewhat, but he was more intent on their getting as many miles between them and Wolverton as possible that first day before the alarm went out to the state authorities to look for them and possibly send deputies to round them up.

The rail line the tycoon had built to carry the crowds from the cities to Wolverton was also overgrown, the train long-since sold or retired to rust away in a distant rail yard. But it led the way back toward civilization.

Yet Striker grew uneasy. He took a sharp turn away from the tracks.

“What are you doing?” Clarence called after him, stopping alongside the tracks.

“They’ve expecting to find us by the tracks, that’s what!” Striker laughed. “Why help them catch us?” Clarence felt the sting of Striker’s corn and could find no answer to that. But to walk straight into the wilderness—that would get them where? They might perish from hunger and thirst out there! How would they make it through all that desert and mountain country?

“We have no choice. Are you coming with me or not?”

Clarence knew Striker was right. He had to follow Striker. Only Striker seemed to know what to do next.

They continued to lose themselves in the wilderness, putting miles between them and the rail line, so that they felt they could slow down their pace and go more slowly.

What was the big hurry if everyone would be looking for them in the wrong place?

The events that followed disproved everything Clarence thought they had going for them.

The next day, after sleeping out in the open under some half-dead, scraggy trees, the boys were spotted by two men on horseback, and they had to run for cover, reaching a deep riverbed that was spanned by an abandoned trestle. The tycoon had begun another line, one he planned to reach over the mountains of Nevada to the cities of Las Vegas and Reno. This was the fragment of it, left as it was—a trestle with a few miles of track on one side of it connecting to the main trunk line running to Wolverton from the coast. Even the trestle was not passable. The ties and rails were never laid; only the supporting beams were in place and spanned the river bed.

“How’d they find us so quick?” a panicked Clarence cried to Wolverton as they dashed to get away into any cover they could find.

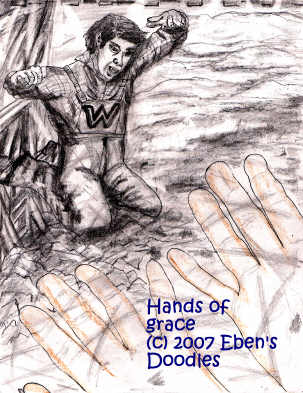

Striker didn’t answer, his long legs carrying him down the steep slope to where the trestle started across the dry river. One side of the gorge was treeless and without a blade of grass. But the rock on the opposite side was porous and was trapping the water in the slopes and cliffs, and they were thickly wooded. If only they could get across the trestle, they could possibly get away, Clarence saw. That had to be Striker’s plan now.

He climbed down as fast he could, with the pursuing state deputies leaving their now useless horses to follow on foot.

Striker now used his training as “Percival Arbogast of the Flying Arbogasts” in Coxey’s Four Ring Circus to leap and catch each girder as he made his way through the trestle’s underpinning structure toward freedom on the opposite bank. They could have run from bank to bank in a couple minutes, but the men on foot would have ridden them down in a minute. There was no other way than the one Striker had chosen, Clarence saw.

The men below them ran across the dry course of the dead river to see if they could catch the boys above them when they descended. But Striker, Clarence knew, had already outwitted them. He would simply climb up on the end of the trestle where some ties and rails were laid, and then run the remaining distance and slip into the woods and big rocks. No horse could make it in such terrain on the other side, it was so rocky, steep, and forested.

Could he do the same? Clarence wondered. He had no choice but to try. The men, seeing this, stopped in the middle of the riverbed, and started shooting because it was just too high and dangerous a climb for them to make it up in time to intercept the boys. But that didn’t matter either how much they shot at them, Clarence thought. He didn’t care if he was shot—that would be a quick end for him at least. He only feared capture and a long imprisonment for aggravated arson, or a hanging if his uncle’s death was ever charged to his doing.

As for Striker, Clarence considered him as one who lived a charmed life. He was just too lucky and agile and smart to be caught. Whatever mistake—someone had whispered embezzlement to him once—that landed him at Wolverton, he had long since corrected. No one could stop Striker now.

Hurrying to catch up, Clarence tried to copy Striker’s every move and leap. It all went well for both. He was gaining even on Striker. Striker wasn’t even worried, Clarence could tell, by the fact they were being pursued so closely.

“They’ve given up on us!” Striker laughed as Clarence came close enough. Striker seemed to want to give Clarence time to join him. “You’re doing great,” Striker encouraged him. “We make a great team of bandits and desperadoes, don’t we! This is better than reading about periwinkles in Worcester, isn’t it?”

Striker smiled and gestured to him to hurry up. A particular last gap needed to be jumped by Clarence to reach the last set of girders.

“Just a little bit more and we’ll be on our way again, with no more worries of anyone following us! The country is just too wild from here on for them to even consider it, my friend! We can eat rabbit and quail, which I know how to catch plenty of, so we won’t starve. I’ve got matches for starting a fire, and there’s dry wood around here to burn. We’ve got it made, Gypsy boy! Now come on, jump, you can do it!”

“Yes, I can do it!” Clarence thought. “This is the last big jump, and I’ll have it made with Striker!”

Clarence smiled as he leaped toward Striker, his hands outstretched to catch the beam he needed to catch to reach Striker’s perch.

At that moment, however, Striker used his circus training and struck out with own legs as he swung on the beam. The move knocked Clarence backwards with a big, expertly aimed kick.

Twenty feet down Clarence hit beam after beam, then dropped down onto the rocks below. Striker, looking down, pulled some papers from his shirt and let them fall and scattered round the body. “Have some perwinkles, sucker!” he shouted down.

A deputy, seeing this act of deliberate, cold-blooded murder, turned confounded to his partner. “Why’d he do that? They both coulda make it away now! Who could be that mean and heartless to do that to his own buddy? Was he thinking the other fellow was slowing him down too much? I seen many bad things in my time, but this takes the cake!”

His partner was staring upwards, watching the last of Striker climbing to freedom as quick as a mountain goat in his own mountain territory. A moment later Striker had vanished in the immense maze of rocks, canyons, and mesas beyond, leaving the crumpled form of his companion.

The deputies, still scratching their heads with disbelief, made their way over the rocks to examine the body. They picked up the papers. They found out they were court and school records, detailing Clarence’s various incarceration in San Francisco for petty theft and vagrancy and also reports from law authorities working on his Prescott, Alaska Territory arson and homicide case. The latest dated, composed by a chief prosecutor for the state, recommended that the boy be returned to the state court as witness in a murder case. The prosecutor claimed that they were sure to convict and hang the man if they had Clarence’s testimony, for Clarence had been a close friend of the arraigned. The letter detailed how often Clarence had helped the law in the past in like manner, by which he had gained clemency for his own thefts when he had been caught along along with others.

In a bind, Clarence the rat and pigeon would open up to any officer in interrogation, and his friends could all go hang as long as his life was spared! In fact, one man had already had his neck stretched, thanks to Clarence! If that wasn’t enough, he had burned down the whole town of Prescott in the Territory of Alaska just to get away from his drunken uncle, Arthur Prescott, or, more commonly, “Sourdough Scottie”! The records told the whole miserable story, and Clarence’s buddy decided he would even the score for everybody once and for all, and not risk Clarence’s squealing on him!

Why he had waited was obvious—in school he would have been hauled away immediately, but in open country he could easily dump Clarence and get away.

Yet for decency’s sake, they carried the body to another place, and in the dry river bed they made the grave, piling rocks on the body to keep off the coyotes and the crows.

This fierce-looking avenger waited to thrust his uncle to his doom, but Clarence did it on his own, again without crying out for any help. Then he saw the long-haired angel again standing beside him, waiting to strike the man who was beating, then was strangling him at Wolverton for things he hadn’t done wrong, waiting in vain, for Clarence never once cried out to God whose servants were all these angels.

It continued like this. Angels, angels, angels, the blue ones or some black as midnight, attending his footsteps all along the course of his short life. Even when he, still trusting Striker, leaped out toward the beam where Striker waited, there was an angel hovering beneath, waiting to catch him and stop his fatal fall.

But, without a word, he plummeted down past the angel’s pleading face and through the golden ring of his waiting, outstretched arms.

Preserved in that way until the 21st century, they were next transferred to computer archives. This data found its way like a tributary stream into the vast Amazon of criminal information that was the F,.B.I. and C.I.A.’s combined master data bank. One thing Wolverton always did with inductees was remove a specimen of hair from each boy’s head, and it went into the boy’s file with his records. Someone in the Historical Society found these specimens, and sent them along to the F.B.I, which in turn submitted them for DNA analysis and identification.

Clarence’s DNA and his entire life was mapped out in this way and preserved. Eventually, the 22nd Century’s genotype bank at Tutasix in the Aleutians obtained the file, and when the White Ship’s crew of the Cybernauts was chosen some millennia after that, the Black Ship’s crew was also being selected; thus, Clarence’s file was drawn, and Clarence found himself flown down to a pirate ship.

There his old school gang nick-name stood him in good stead as he was made known to his crewmates, all of whom were pirates and professional criminals—-thugs of no misgivings whatsoever, able to commit any kind of atrocity they put their minds to.