“What will the young gentlemen have to drink?”

Chillingsworth glanced with evident disdain at the bald-headed steward waiting on them and demanded bottled distilled water with ice. “With fresh ice, not something setting for hours and hours in some dank, unwashed machine or receptacle,” he expressly stated to the surprised waiter. “I can tell the difference when ice is fresh and when it is stale, so don’t try to trick me! I’ll drum you out of your job if you do!”

Avoiding the shocked waiter’s eyes, Nilsson colored more than a bit. He saw he already needed something more fortifying.

“The L.G., please," he somehow got out in a choked voice.

Finally, the waiter came bustling over to their table, perspiration beading his forehead. “I’m very sorry for the delay, gentlemen, but we don’t often get orders for fresh ice, and as for ‘L.G’s we had to look it up in Duffy’s, which we found in storage where we keep the really old mixer manuals--printed books, to be exact. Please understand if this takes some time.”

Still taking responsibility for the luncheon, Nilsson turned a brilliant full smile to the poor man, and his eyes looked as if he were in rapturous love with the whole world.

“Awfully sorry to put you and your chaps to such trouble! But I’m sentimentally stuck on that obscure, old drink. You see, my grandfather made it for me when I graduated from university--simply can’t abide any other whenever I think of him.”

The waiter went all mush in response to even this slight degree of Nilsson charm, which agreeably turned the heads again to him, not Chillingsworth.

By this time Chillingsworth had taken a careful sip of his ice water. He wagged a stubby forefinger at the waiter, eyes glaring. “What is there about 'fresh' you don't understand? This ice is distinctly NOT fresh! I know I ordered fresh. I simply detest aged ice! Take it back and bring me fresh!”

In those circumstances that was pretty dreadful behavior, of course, but what was Nilsson to do? Grimly, he went on with the agenda for the sake of the school tie. They quickly disposed of what they wanted for lunch, and the waiter moved off a little less quickly than they had ordered, gentlemen from other tables leaning over to whisper encouraging things to him as he passed by in disgrace.

Chillingsworth, the ice business dealt with, then leaned forward, and Nilsson had the distinct impression a very bulky sea creature of some sort, an elephant seal perhaps, was about to quote something overheard on shore.

“To some maybe,” said Nilsson, and he gulped a deep swallow of Scotch. “But I see it’s necessity. Since Arab fundamentalists have completely taken over the old Arab league--which all our money and alliances could only postpone--law needs to be honored more than ever.”

The waiter turned to Chillingsworth with a glass of chilled water. “The club is out of fresh ice,” he informed him. Chillingsworth, in response, did not look up as he replied, “What did you say?”

The waiter repeated his words, and Chillingsworth’s hands clenched on the table. Room temperature, at that moment, seemed to plummet. Tables away, an octogenarian sneezed. “I thought as much,” replied Chillingsworth, though he had to drag out every word for the effect. “The whole world has fresh ice, but you haven’t!”

All during this Nilsson, looking on, felt like sliding down from his chair and crawling away. But this second bad moment, occasioned by Chillingsworth’s latest broadside, also passed in time. They were served the Reform Club luncheon special--Yankee lobster from “Maine”--the geosynchronous lobster factory by that name presently flying round the equator.

Arab fundamentalism was not the only world crisis. Since colder weather had set in, farmers had been forced south and northern agriculture suffered, but not so the fisheries.

Though the Spiny Lobster had fled from Bimini to more southern shoals, northern, clawed lobsters, once over-fished to near extinction, had made a tremendous comeback by way of a clever algae that reproduced perfect lobster in taste and texture. It not only created a lobster substitute but fed the real variety, raised in the same stations, for those who still could afford it.

Eton’s star alum and endowment fund raiser dropped his fork. He stared at his schoolmate. “But that’s been tried before and it failed.” Nilsson’s eyes widened as he stared at Chillingsworth. Utter, profound disbelief took over where surprise left off, and he felt forced to speak his mind. “Take a lesson from that other ‘ultimate weapon,’ the old atom bomb, which led to a nuclear arms race and nuclear proliferation. No, only international agreements and respect for them will achieve the climate for enduring peace. That’s where people like me weigh in the balance, if you will pardon the judicial allusion.”

That said, he settled back in his chair, an ironic smile flickering on his lips.

Chillingsworth, looking unimpressed, wagged the forefinger at Nilsson. “Nils my boy, you speak too hastily. You don’t know what I’ve been working on, or you wouldn’t jump to specious conclusions like those you’ve just offered. I thought you men of the law were more circumspect about forming preconceptions, but, obviously, you’re an exception to the rule.”

“Are you sure you can tell me, if it’s as important as all that? What about compromising national security?”

Nilsson put it as diplomatically as possible. Chillingsworth smiled at Nilsson’s obvious ploy to evade hearing about it. He wasn’t buying, which his tone showed very plainly as he demolished Nilsson’s remark.

“Can’t you do better, Old Man?” Chillingsworth laughed. “That’s an archaic, pointless concept too--’national security.’ The world is becoming one entity, Arab fundamentalists included, who, as they observe their declining oil revenues as the writing on the wall, will come around to our point of view. Once they’re dealt with sufficiently, we can progress to the inevitable.”

“And what is ‘inevitable’?”

“A world state, of course!” Nilsson’s mouth fell open. He had so wanted to stop the conversation when he saw how it was going. Now he half-believed Chillingsworth was not pulling his leg. Yet another part of him insisted it couldn’t be--the Chillingsworth he had known couldn’t be involved in weapons development--he wouldn’t even allow a runaway laboratory rat to be trapped in his rooms at Eton! Drawing himself up with a businesslike air, Nilsson threw a subscription card on the table--determined to see the thing through regardless of the conversation.

“Now about our pledges? I’ve come to collect yours as a rep of the endowment drive committee. If you would like a listing of the improvements it will eventually finance, I will be happy to--””

Chillingsworth’s face suddenly lost its look of secret triumph and he frowned. “Oh, never mind that. I’ll pledge 5 million, no, make it 50 to make it worth my while to get proper mention in your alumni promo rag.”

Heads positively jerked their direction. And Nilsson looked at Chillingsworth with the same leery expression as when his schoolmate had first announced his ultimate weapon. “You couldn’t mean it! I haven’t got pledges anywhere near that. Most of us are tied up in long-term investments in near-Earth agri-colonies. You’ll impoverish yourself!”

Nilsson stared at the speaker, at last convinced that the normally soft-spoken, self-effacing Chillingsworth was a thing of the past. Before him sat a stranger--spiteful, petulant, self-important, bombastic, and utterly careless of his patrimony. But a brilliant weapons specialist with an ultimate weapon? He still wasn’t sure about that.

“And what exactly is your work, and this ‘ultimate weapon’ you spoke of earlier,” prompted Nilsson. He was now quite interested and in the mood to be amused since his part in the pledge drive turned out to be such a success.

All the distinguished old Reformers at nearby tables quit talking. The aged waiter came with a pitcher of more chilled water. Annoyed by the interruption of their privacy. Chillingsworth turned to Nilsson. “How about us taking a walk to the river park. It’s gone a bit stuffy in here, don’t you agree? And we can see how they’re getting on with the Geo-Dome project.”

Nilsson looked down into the river, which ran free of boats of any kind now that the Thames all the way to Gravesend had been declared a restricted nature preserve. Iced over from September to late March or early April every year, the river had lost its prime, historic, commercial function while becoming clean and beautiful for the first time in many centuries.

From their vantage, without tall buildings in the way, they could see the latest progress on London’s ultraviolet-shielding, heated dome. Its geodesic framework--the most gigantic engineering feat in history--was completed. Fitting of the translucent but reflective panels might take another decade. But it would be finished, despite unthinkable cost and difficulty of construction and shield London not only from the cold but ever increasing levels of solar ultraviolet.

The world scientific community, though they had never come to agreement why the Earth was baking and freezing at the same time, was unanimously agreed that domes, at least over major cities, had become a necessity.

Thanks to them, Earth’s deteriorating weather wasn’t a crucial factor in food production anymore. Instead of constantly trying to develop new cold-and-drought resistant wheat and rice (or growing food crops and raising dairy herds in gas-heated sheds like the gas-affluent Dutch), agriculture had plowed virgin territory in space.

The last world-wide food crisis was in the 20th Century, brought on by world-wide droughts, shifts in the monsoons, ocean currents, and wind patterns, and severe southern frosts--which had turned agriculture to developing single-cell protein/petrol cultures, or SCP food production.

From there the logical outcome was genetically-engineered, superproductive “smart algae” that produced everything from plastics to clothing fibers to chocolate and Maine lobster. There were even algae that could crank out excellent Scotch in unlimited quantities.

“Now, you were going to tell me more about your work and this weapon of yours?” he said, trying to keep his voice steady. Should he laugh? Should he be serious? Here he had a chemical-biological-nano tech war alert going on one hand, and on the other, an old school chum who claimed to have invented the ultimate weapons!.

“But why tell me?” Nilsson burst out before Chillingsworth could respond. “We weren’t all that close at school, if I recall rightly. Why share confidential information now with someone outside the scientific and military industrial establishment. You could go to jail for that, I suppose.”

This was the lance Nilsson had kept in reserve. Chillingsworth’s mild voice took on a hard edge, as if his schoolmate’s irony and sarcasm maintained through much of the conversation had finally cut to the quick.

“You always were honest, to a fault, the few times we spoke to each other, as I recall. You didn’t notice, no doubt, but I greatly admired you. Sports and academics and the girls from the town, you mastered everything, whereas I couldn’t seem to find myself--not until lately, that is.”

He paused, reaching down for a pebble, which he threw at a floating Harlequin puffin--a polar species that flocked along the Thames nearly year-round. The bird screeched as it was struck on the wing, and it beat the remaining wing to flee, as Chillingsworth proved an expert shot.

“Why, Nils, you look at me as if I’m a cruel beast! Well, I don’t like biota running stark free like that. Belongs in a cage in a lab, serving mankind with valuable scientific data. If I have anything to say about these creatures in the future, well--where was I? I want you because you can do something for me. I’ve created the means to stop wars forever, but you are presently studying the ways to make men law-abiding or, failing that, pay recompense for law-breaking, all on an international scale. Your expertise dovetails with mine, as I see it. Together, we can scuttle the antiquated, inept United Nations and devise a new system for humanity, one in which the world will reach its highest potential and--”

“Wait a minute!” cried Nilsson, holding up his hands. Things, he saw, were getting out of bounds and becoming far too serious for a college subscription drive. If the sirens would only stop so he could think! “You’re going far too fast. Just what is the basis for this collaboration. You’ve not yet told me what your invention is. After you do that, I’ll ride with you to inspect your prison cell.”

Now Nilsson cared little about the latest developments in the scientific realm. He wasn’t interested in science and technology, though his scores had been among the highest both at Eton and Oxford. Back then Chillingsworth hadn’t been fond of them either, he recalled with a jolt. But he badly wanted to bring the disturbing conference to an end--settle it one way or another. Was Chillingsworth, this new Chillingsworth, an absolute humbug, or was he really on to something significant?

“To explain it, I must show it to you,” replied Chillingsworth sweetly. “I doubt you would appreciate a more scientific explanation."

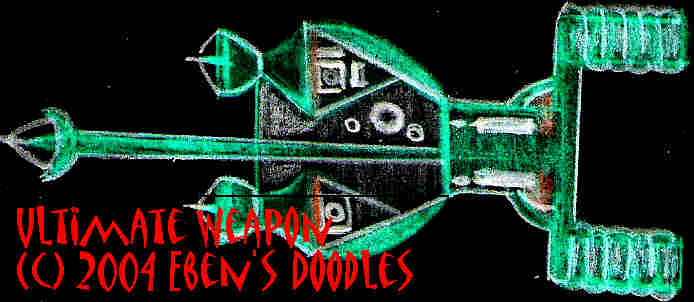

He held out something drawn on a square of white table napkin, and Nilsson looked at him, wondering if he had lost his mind.

Chillingsworth smiled benignly as if at a simple child. "While that old fool back there was wasting my valuable time, I drew this little sketch on a napkin of my ultimate pacificer or ultimate weapon, its use determined by the responses, pro or con, that my programme receives from the nation states, of course.”

Nilsson stared at Chillingsworth's pencil rendering, then smiled, using his old charm to smooth over his irritation, which smarted the back of his neck like prickly heat. “You hit the mark there. We Scandinavians have always been a stubborn, practical, “show me” lot. I’ll be happy to see this thing demonstrated, when you find time to, er, arrange the showing.”

By this time, Nilsson really had to go. He thought this would be the end of the matter--for himself at least. He had pressing legal duties at the World Court in the Hague, a particularly nasty, touchy case involving Arab fundamentalist terrorism. After he sincerely thanked Chillingsworth for the stupendous subscription, they set a date to meet again, and Nilsson's heart sank as Chillingsworth showed he wasn't letting Nilsson off as he pressed him for a firm date for the next meeting.

The next time was to be Chillingsworth’s haunts, a facility run by an elite experimental research group headquartered in the Cotswolds.

"Oh, well," thought Nilsson as he hurried away, "a lot can happen before then to distract him, or make the showing impossible to carry off on that date. Maybe then he will forget all about involving me in this mad scheme of his!

The Cotswolds! How perfect! Virtually uninhabited barrens, they seemed the perfect retreat for scientific skull-duggery of the type Chillingsworth had described to him. He followed Chillingsworth’s directions and found Loewe-Optikon Internet Systems. It set a mile from town amidst rolling hills of intermingled sand, year-round frozen bog, and tundra. To avoid the worst of polar storms and a frequently rampaging river, most of the facility lay below ground, he discovered.

“You’re three minutes late,” Chillingsworth observed, wagging the forefinger. “I can tell punctuality isn’t one of your strong points, my clever friend.”

As Nilsson’s eyes rolled up in their sockets, Chillingsworth led him down to his office and laboratory. There was a security scan too, during which Nilsson, still edgy after the initial rebuke and hating his surroundings, behaved himself with ill grace.

It was a strange thing too. Despite the conversations in the club and on the river park bridge, he thought he was more prepared for Chillingsworth the rabid, world-class research scientist but the second meeting came as an even greater shock. Chillingsworth’s lack of drive at Eton still made the present Chillingsworth so improbable. Too rich for his own good and not overly motivated, the younger Chillingsworth was a poor bet to make the major leagues of anything--much less command the Ship of World State. Everyone knew that. So what had changed him to this dynamic phenomenon he now was? Nilsson wondered again in the man’s utterly disorienting presence.

For Chillingsworth was a whirling cyclotron, despite that annoyingly mild, characterless face like a seal’s and that disconcerting pair of too round, unblinking eyes. Everyone they passed in corridors or in the various labs deferred to him with a nod or respectful remark. Nilsson was ignored--a new experience for him. Obviously, Chillingsworth had made it a practice of bringing people to view the project and he was just another guest--a “non-professional” cipher subsisting outside the scientific pale.

The new Chillingsworth wasted no time. He practically ran down the halls and could not get to places fast enough. “Step along a bit more briskly, will you?” said Chillingsworth when Nilsson lagged.

Wasting no time, the guide got right to the point as he turned to Nilsson. “Leaders and generals on both sides, East and West, Arab and United European, have already been here to see it, to compare it with their latest weaponry and see who’s got the cutting edge. It’s completely open for inspection. That’s why there’s no special security net and I can bring in non-combatant types like you. Now for the demonstration.”

Nilsson’s face fell. “Well, what’s so special about it?”

Chillingsworth smiled indulgently and removed from a carrying case an object that Nilsson could identify from the crude sketch of it he had seen back in London.

Holding it as if it were something very dear and sentimentalized, like a childhood toy, the weapon's maker faced Nilsson with a kind of "reserved pride" glowing in his eyes you might expect to see in a professional who has done something truly exceptional to make it over the top in his field.

“I call it a “thought-weapon,” or TW. Despite its nice theoretical possibilities, I knew nano technology would never be the thing, for two reasons: 1. it is relatively nonselective, for a molecular dis-assembler cannot tell the difference between an Arab and a Westerner, and 2. Anyone with a good enough lab can come up with a deterrant. This time, there’s no deterrant, and I can eliminate precisely whomever I want.”

He held it up without aiming as he faced a hologram target at the end of the room. “No, the demonstration will explain better what it is than a thousand of my words. I will only say that ACTIS--Advanced Computed Internet System--was of some slight assistance. The rest is all mine. You’ll soon see.”

The tiny dish-telescopic sight set at the head of the weapon gave a nasty, high-pitched buzz and rotated briefly.

Nilsson frowned--but not for long.

It stopped scanning. Then a beam of light shot out of the right barrel, followed by a second, more sustained laser strike from the left barrel. The hologram’s head exploded like an over-ripe melon struck with a sledge hammer.

Nilsson felt he had been hit too. He gasped, then cried out. “But you didn’t tell the bloody thing to attack!”

Chillingsworth laughed. “That’s not necessary. It already identified the object as the enemy and since this is an attack weapon it naturally attacks. Scanned affirmative, an object is automatically neutralized. The beam that does it carries a pulse of twelve trillion watts, which is, I think, sufficient deterrence, since the same wattage produces hydrogen fusion, as you know. Nobody but myself will ever know the primary sub-stomic nergy source contacted--and I will die with the secret!"

Chillingsworth, in answer, hit a button on the console nearby and the hologram’s previously programmed thought-patterns came up on the screen.

The inventor went on, patiently reducing the product of his genius to the simplest terms possible so that Nilsson might grasp the rudiments. “There are some bugs and limitations in the thought scan system, or TSS, but it’s able to identify deviant thought-patterns, as long as they aren’t too subtle. We don’t need them too subtle, however.

Since the Arabs are fond of using human waves and have personnel to throw away, most people we are up against are the common cannon-fodder type, who won’t be plotting strategy or anything particularly complex and arcane. Now we don’t need any other weapons.

This one is sufficient to clear the boards of all the Arab armies they can put in the field against the West. But Western strategy needn’t begin there. The supporting populations and administrations can be eliminated before war even begins. As no army can maintain morale without a country behind it, the war is over practically before traditional weaponry, even missiles carrying multiple warheads loaded with nano tech disintegrator machines, can be fielded.”

Chillingsworth gently, even tenderly, laid the thought-weapon down on the table. “Impossible, dear boy. They already have the old ACTIS hardware and that is light-years away from what I’ve designed. In that system the ‘camera’ was an X-ray device that fired a pulse of two million electron units capable of penetrating 6-inch steel plate. Are you familiar with the workings? I thought not. Well, sensors measured the attenuated beam and relayed the information to a Cray. The computer then made an image of more than a million electronic squares and enhancement brought out detail. It was useful for imaging defects in hardware of various critical types, but no one ever thought it might be adapted to human thought patterns. How I achieved that is a secret I will carry to my grave. Besides, they need my protective password and programming to make it work. I alone have access, and to make each weapon operate for a selected number of “strikes” the computer system built in must tie in with my voice command, which cannot be duplicated, giving me total control over the war effort. This prototype can be stolen, but it’s useless without my commands--which can’t be tampered with without blowing up the gun. And they haven’t stopped me because I’ve already told them about it. They know it will never be used against them--precisely because I have a higher use for it than terminating Arab fundamentalists--who really aren’t a threat to the world, by the way.”

Chillingsworth stroked his thought-weapon as he had once stroked rabbits and kittens before he committed them to water, chloroform, knives, and other warm-up, proto-scientific research. “No, you aren’t listening. War such as you describe simply won’t happen. I know, because this is the deterrent. Let the politicians on our side continue to rattle the latest lasers and the Arabs their old and messy but still rather frightening chemical and biological weapons. That is mere posturing to save face with their constituents. The treaty, when it comes, will bring us both together on the same side.”

Chillingsworth smiled with compassion at Nilsson’s response. “We’ve got a lot to discuss, I see. But I’m sure you will come round to my more rational point of view. If you will, one last demonstration. Please hop up on the dais.”

Nilsson shook his head. He already felt sick to his stomach from the demonstration and the discussion as well. “You really don’t think I’ll do it, do you? I saw you explode the hologram’s head. Naturally I prefer mine as it is. Why, it could be... the end of my law career.”

With misgivings, Nilsson gave in and stood on the violet-glassed dais. Though he couldn’t help shivering once he started, he had an odd feeling he wasn’t going to go out of Loewe-Optikon the way he had entered.

“Okay. Now just think about the things you hold true and valuable--your ideals, belief-system, foundational truths to live by,” Chillingsworth instructed him..

After his talk with Chillingsworth, Nilsson was already primed for that sort of thing, and didn’t have to do much soul-searching.

Chillingsworth lifted the ultimate weapon and fired the first scanning shot, then the second for termination. The screen showed Nilsson and his head vaporized, with the front of his face being blown off--his nose and one eyeball flying up and hitting the ceiling.

Nilsson’s apprehension was right. Watching the big screen overhead, Nilsson let out a loud shriek this time and nearly leaped off the dais. Without giving him time to recover, a read-out of his fatal “deviant” thought-patterns flashed on the screen.

Nilsson stumbled as he got down from the dais. Dazedly, he felt his head. It was all right, one piece, but he felt he had been beaten up and somehow violated.

But, worse, he saw that he was nothing but a fool for coming. Loewe-Optikon was Nilsson’s element, not his. This time he had swum beyond his depth and sharks were snatching big hunks out of him. Feeling numb, chilled, and virtually dismembered, Nilsson turned to go.

“But no, there is more I wish you to know,” said Chillingsworth, catching his arm.

“Sorry, I must be getting back. You can’t--”

“Of course, and I won’t keep you longer than a few more minutes. But you should know that this weapon is only part of my strategy to save world civilization from destroying itself. Terminating thought-deviation in the manner I have demonstrated is, admittedly, messy and emotionally disturbing. I can see that plainly enough on your face! But I thought of that and made provision. Thought-weapons are so public, everyone sees what they do, which could lead to civil unrest when large numbers of thought-deviants (TDs) are terminated in crowded, public places, so my greatest weapon has to be unseen, invisible to the public eye. The same device connected to hidden, unobtrusive surveillance cameras and a globally orbiting system of satellites; they will identify and track TDs so that they can be rounded up and sent to thought-correction centers, or TCCs.”

Nilsson groaned right in Chillingsworth’s face. “But that means no one will be free to think one thought of his own! The world state will control even our brains! Or blast them from our craniums if they are ‘deviating,’ as you put it.”

Chillingsworth smiled indulgently. “Why do you find that so offensive? The purpose, let me remind you, is world peace and stability. We simply can’t have peace with everyone free to think unsociable, uncooperative thoughts, can we? As I was saying, my thought-detection system of orbiting thought scanners will tie in with regional thought monitoring centers (TMCs) on the ground. Whenever an individual is identified from the air as suspect, the data is sent to the monitoring center for appraisal and implementation, and--”

There went his eyeballs and nose! There his brains! And over there the top of his skull!

He was forced to wonder, however, about his reaction. With his Viking background, he thought how Chillingsworth’s weapon was no more lethal and gory, in the end, than a Viking blood-ax. Both split craniums and exploded the contents with almost mechanical precision.

All that was true. Yet when his forebears were making lightning raids and burning and sacking every French or Irish village their dragon ships could reach, were they concerned with how people thought about Vikings, their beliefs and ideals? Was that the deciding factor whether they lived or had their brains smashed? No, his forebears were far too practical. They wanted loot and a quick getaway--not control--the one thing Chillingsworth really esteemed. Not money, nor wine, women and son--but pure brute power, that was the whole aim of this cold, calculating, heartless and soulless monster!

“Why, he’s a hundred times worse than old Schickelgruber, and he was pretty nasty, far as he went. Before he dosed himself with Ajax cleanser laced with cyanide in that bunker in Berlin, Schickelgruber nearly had the A-bomb, and would have used it on Britain and America without a moment’s hesitation. But Marcus? Marcus? Ho! He’s got something more destructive, ultimately, than the entire, outdated, nuclear arsenal of the West, and he fully intends to use it on us all.”

Nilsson couldn’t bear it. “Aaaaggghh!” he cried, stumbling from his hovercar at Folkstone and drawing attention as he ran toward the gates. The human mind can grasp only so much horror at a time. What Nilsson could plainly see was enough to blow his mind like a TW--only he hit the bar on the Le Shuttle and drowned himself just in the nick of time.

Nilsson winced as if he had been struck. He suddenly felt his face and the back of his head. He wasn’t coping very well lately. His head was still there, but his hair had not been combed--what he had left to comb, for it had been fast falling out lately. His tie looked slept on. He hardly tasted the food Chillingsworth ordered.

Chillingsworth never looked better, from head to toe. He brimmed with energy and purpose and, the old brown herringbone shucked, shone with elegance in a new suit, and he had thought ahead and brought his own container of fresh ice to put in the club’s chilled distilled water.

“But this juggernaut of a world state you’re wanting to set up is despotic--it’s sheer unadulterated tyranny!” Nilsson argued hotly without preamble. He didn’t care now that that the few diners left in the room turned toward their table, their snowy eyebrows lifted.

“Let them get an earful!” Nilsson thought. “They need to know what someone of the younger generation is going to do with their country and the world!”

Chillingsworth was the cool one as he carefully spooned four spoonfuls of fresh ice to his water. He studied Nilsson carefully before replying. “So? It’s tyranny with a purpose--that makes it different from anything in the past. Freedom allowed people and nations to be what they wished--and we see the impossible, chaotic situation that brought us all to! No, we need to control this runaway world, control with a civilized purpose. My device--both visible and invisible portions--will make that possible. No one before could achieve that. Not Caesar, Charlemagne, Napoleon, and all the rest. The reason is they did it for their own selfish advancement, whereas I am acting in behalf of others and have nothing personally to gain.”

Chillingsworth gazed at him soberly, reflecting for a moment, as he sipped his ice water. His mild demeanor was worn thin-- cold steel glinted in the round, moonlike, unblinking eyes. “I see you are determined to maintain certain obsolete thought-patterns and are opposed to positive change, both for yourself and world society. Oh, well, I had hoped for better from you. I gave you the benefit of a doubt, because we wear the same old school tie, and you’ve wasted my valuable time. To oppose me now will do you no good and me no significant harm. I know what is best for the world and fully intend to implement it. This movement I have started cannot be stopped. It’s as simple as that!”

This bald statement of Chillingsworth’s creed must have torn it. Nilsson lunged out of his chair and it overturned The waiter dropped a serving platter on his own foot, then hobbled toward them.

“We’ll see if it cannot be stopped!” he found himself shouting at Chillingsworth, his rage flowered into something uncontrollable. “What if people don’t want this ‘World Union’ of yours? What then? If it goes belly up on you, what will you do then, my friend? Fly to Mars--or if that’s too close for comfort--to that blasted, frozen gasbag Uranus?”

He was looking for a taxi outside the entrance when an antique internal combustion car drove up. The door opened and an elderly man climbed slowly out. Nilsson waved to flag a cab in the mass of traffic.

“Excuse me!” said the old gentleman.

Nilsson looked and saw no one he recognized.

The old man extended a badly trembling hand which gave no pressure in Nilsson’s. “I am so glad we’ve met at last. I am Marcus’s father. You were my son’s idol at school. I’m afraid my wife is not well and couldn’t come along. I heard just lately of this meeting and rushed over. Is there somewhere we could go and talk. I really must speak to you.”

“Sorry, I’m in a hurry. Might you drop me off at the Channel tube? We can talk on the way.” “Perfect!”

Nilsson caught a glimpse of Lord Nelson’s statue in Trafalgar Square as they took a ramp to London’s connecting Tube station to the old Channel expressway. At night the garish red and blue illumination round Britain’s greatest naval hero of the Napoleonic Wars was almost blinding, but it wasn’t the intensity that made him shut his eyes for a moment.

The elder Chillingsworth sighed. “No, I’d rather it be that. They can be bought off with a certain sum and the matter forgotten. Rather, it’s the world he’s after. But what in heaven’s name has got into him? Ever since his majority and we gave him back all his old things he changed utterly. We don’t know him at all now! Is he mentally deranged, do you think? There must be a logical reason!”

Nilsson slowly shook his head--then quickly felt of it. Pulling his hand sharply away, he turned to the grieving, bewildered parent. “I am so sorry, but I cannot help you in the least. If there is a reason for it, I have yet to know it. It would be a simple matter if he were truly mad--which I can’t say he is. I’m afraid that leaves us both in Egypt, doesn’t it?”

Though Lord Chillingsworth’s line of questioning had got nowhere with him, the question would not die and let him go so easily. What had got into Chillingsworth? Changed him so radically from the phlegmatic lump of a rich boy he had been at Eton? The question was a continual torment to Nilsson, robbing him of sleep and ruining the quality of his work during the day.

The question would not go away even though no one else but Nilsson and his aged parents seemed to be asking. Why it obsessed him, he could not explain. Perhaps it was his close contact with world politics through his job at the World Court. He could not avoid Chillingsworth. Day after day the implications of Chillingsworth’s policies weighed on every decision the World Court had to make. It plagued him to the point his wife grew concerned as empty bottles started turning up everywhere around the house and his moodiness increased.

His wife turned to him one day after he had been particularly aloof and irritable around the children.

“Henrik, what’s got into you? You should have listened to me before when I said you needed to get away for a change of scene. When you’ve made up your mind what you want to do, I’ll have mine made up too. At this point, don’t expect it will be all that favorable to you.”

“Just that there has to be a change. I and the children can’t take this continual strain in our relations. It’s destroying us. What changed you? Everything was going so well up to now. You’ve turned into a stranger. I can’t imagine what’s caused this. I’ve actually grown terrified of you--wondering what you may do next.”

Early the next morning, he left the house without his usual breakfast coffee and pastry--the koulouria, sesame-seed rolls their Greek housekeeper-cook baked fresh for him every morning. A note was waiting for Ditti who always rose late--he was flying home. He planned to spend a few days on some quiet island off the Atlantic coast and she was not to worry.

The good wife worried, just the same. Cook frowned and sesame rolls piled up and up.

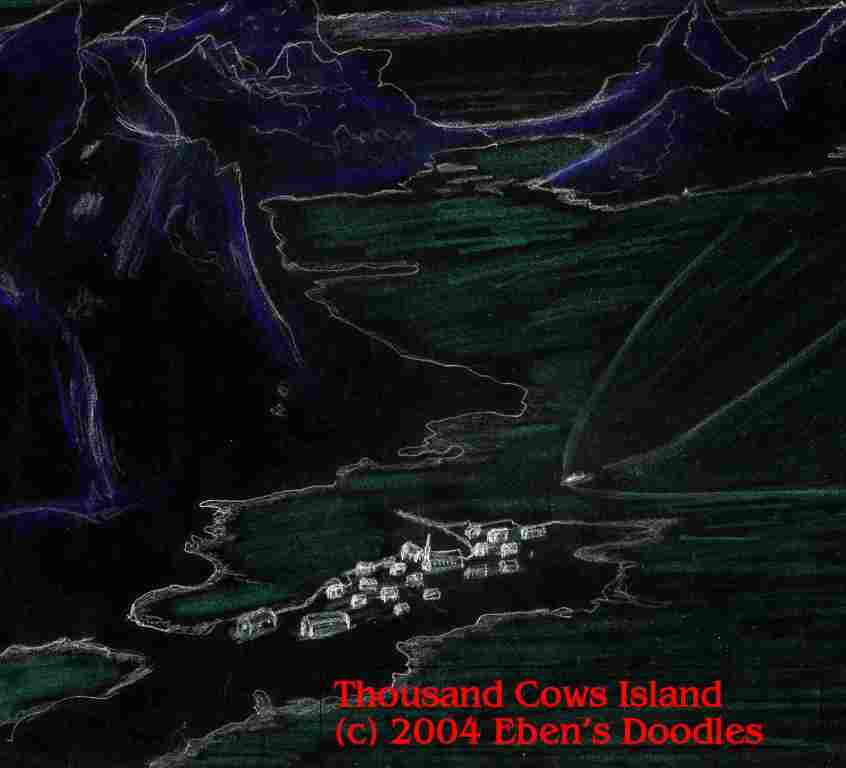

Free of the berg and floating ice, they headed for the uninhabited sea refuge Nilsson had selected. After an hour they both sensed the looming 500-foot sheer cliffs, then heard the booming waves. Within minutes white foamed at the base of the mountainous rocks, their tops swirling. Nilsson had chosen Tusen Kuen, “Thousand Cows,” for his retreat.

“Seabirds and fur seals love it, but it’s not fit for humans anymore, much less milch cows,” the captain repeated “I’ve even heard of sightings of Arctic foxes. A breeding pair must have ridden an iceberg here. Maybe there’s a polar bear or two besides. Are you sure you want to stay a week? I can come for you in a day or so?”

Tryggveson shook his head as he pushed off and left Nilsson on the shore of the isle’s only cove.

“Take care,” said the boatman, not one for saying good-bye after helping Nilsson get his things out of the boat.

Nilsson looked up and around. For shelter there was only the abandoned dairy cooperative. A white, steepled frame church, marked ANNO 1913, stood a hundred yards from shore, and was in remarkably good shape. A tumble down collection of a silent movie theater, cow barns and silos and cottages lay strewn about on the slopes and meadows turned to sand and tundra. The church had just been erected when the dairymen reluctantly decided not to fight the severe cold change in weather and fled to the mainland--all their hard work lost to the ice and snow.

Tryggveson glanced back at the tiny, receding figure on the beach. Just in case, he decided to come back and see how the fellow was doing--not in a week but in a couple days. Instincts and intuitions are active and important to a man grown used to the sea and its dangers, as well as depending on it for his bread and butter. “The gentleman will have changed his mind by that time,” he thought aloud. “Let him spend one cold night by himself and he’ll be counting the minutes till my return.”

Nilsson chucked “It Girl” in the light-green, ice floed water as he scrambled into the boat. They said nothing about his change of mind on the way back. His unshaven, reddish beard beginning to show, Nilsson sat huddled up in his all-weather clothes and kept eyes shut as though he were resting.

“We’re home,” said Tryggveson as they docked. “Wake up.”

Nilsson opened his eyes, startled, as if he hadn’t thought they were really returning to civilization.

Nilsson stared at the curator’s assistant, a typical, healthy, good-looking ingenue you could find by the thousands in Oslo. The only difference was she had so much thick hair, and it was red as an Irish colleen’s, not Viking-blond. “Oh,” he said lamely, looking about to get his bearings. “Thank you, but I usually do my work quite alone, without assistance.”

“If you don’t mind my saying, your Norsk is excellent,” she commented. “You must have the pure blood of Viking ancestors in your veins.” He gave her a puzzled look. “Yes, I do--in fact, thirty seven generations to King Harald the Red. Why--?”

The young woman smiled. “When he called a woman ‘Lefse Lips,’ he probably meant her a great compliment, for lefse was his most prized native delicacy at table. I suppose you could translate it as--”

She leaned over and gave Nilsson a demonstration before he could stand back.

He sat down before a console with ROM. He needed evidence ready for the time when Chillingsworth applied as a candidate that he was merely duplicating some prior candidate’s work. But what candidate? From that point he could not explain why his fingers hit a certain wrong button. Instead of paging weapons development and political science, he got Astronomy.

And out of all the possible prize candidates, he was given this strangely named American--SPACKLE--of Catfish Row, “capital” of the “Sovereign Terrestrial and Celestial Dominion of Mississippi.” It even had a flag--the old Confederate stars and bars, with a slight difference, perhaps denoting the “celestial part”: one star was individually the total size of the others and was marked SN 1987A.

He identified the irregular polar outbreaks of the 20th Century as SN 1987A’s manifestation of a new Ice Age--a question bitterly contested even in ANNO 2145 since it contradicted the favored Astronomical Theory of Ice Ages. He also warned of a “Mystery Spot” invading the Earth, which he said occurred early in ANNO 1912, adding that there probably wasn’t a thing anybody could do about it. The “Spot” was perhaps the factor, the candidate stated, precipitating the explosions of a certain galaxy he named and the star he had discovered just before its supernova.

“If the goldang thing can bang up stars and whole galaxies, what deviltry is it doin’ to Earth and the Sun?” Spackle wrote colloquially in his response to the Nobel Committee’s request for information.

Unfortunately for the Earth and the scientific community, Spackle chose not to hang around any longer to find out and lit a stick of old-fashioned but effective dynamite, blowing himself into star dust the day after he sent his report to the committee.

Nilsson saw that Spackle certainly had been proved right about the premature renewal of the Ice Age. But he looked and found no retractions by Spackle’s Nobel critics. Notified of the candidate’s premature death, they had simply marked the file closed, and turned it over to public access.

After he finished the file, Nilsson had to sit down, even though it was the floor. He felt of his head. Hot and feverish, at least it was there. He took off his shoes, for his feet were burning. “It won’t stop his award coming to him,” he thought dismally of Spackle’s findings. “And, though interesting, it has no logical connection to thought-weaponry and world statism.”

If only he could apply what he read directly to the problem at hand--Chillingsworth and his beastly plans. But how? Again, there seemed no logical connection.

Why, why hadn’t Chillingsworth gone in for orbital agricultural science, which was by far the going thing nowadays? Let him grow fiendish amounts of geosynchronous algae-radishes and algae-carrots and leave the destiny of the human race alone!

He reached and felt of his head, first the back, then nose and eyes.

Nilsson looked, startled, into the concerned faces of the curator and the young woman who had given him her address. “No, I was just resting my dogs,” he said. “I’ve done too much running lately.”

He tried to manage his old, winning charmer of a smile, but this time it fell hopelessly apart on him and he gave up.

The curator and his assistant smiled at the “eccentric American”.

Nilsson, shoeless and uncaring, staggered up and out of the building.

“Morna.”

“Thousand Cows,” mumbled Nilsson thickly. “And do you have an extra pair of boots? I seem to have lost my shoes somewhere.”

Tryggveson turned his eyes up briefly, then nodded. In his business he had gotten used to dealing with some very strange types. Fortunately, most of them paid well without a fuss. “Some men are like that,” he reflected compassionately on the trip back. “This poor wrecked man has got to see the thing--whatever is troubling him--through the whole way, or he’ll never rest.”

He himself had wanted as a teenager to join an Earth colony and live like a frontiersman on a newly opened agricultural station, where superproductive farming with mutant algae went on in ideal conditions. Though you had to sign on for twenty years at a stretch, the pay was many times what he might get on Earth. But an Earth-hugging girl from Goteberg, Sweden, quickly changed his mind. She wouldn’t even consider his taking one of the lucrative laboring jobs on the Uranus rare-gas recovery project. So had settled on the charter boat business in his hometown Bergen, and it suited him, despite the uncertain quality of clientele. He was almost content, he told himself.

“Gud!” said Tryggveson, relieved to find Nilsson looking so rested. There was not a whiff of Scotch. “Gud!”

They rode back to Bergen’s port in silence. Not once did Nilsson reach up suddenly and feel of his head. From time to time he glanced southward toward England with the same blue intensity that had once flashed from the eyes of blond-haired wolves on sleek, black, dragon-prowed longboats.

Henrik Nilsson gave a harsh laugh. “Where did you get that silly idea? Marcus and I are complete opposites, like oil and water that never mix! I could never, never turn into his type!”