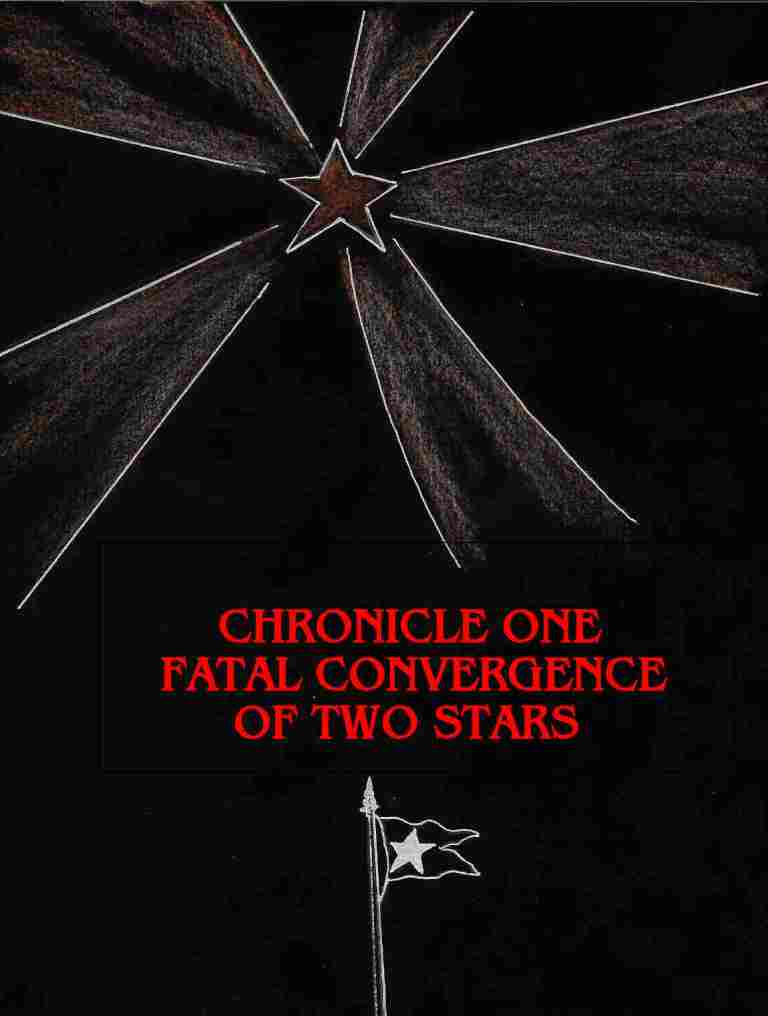

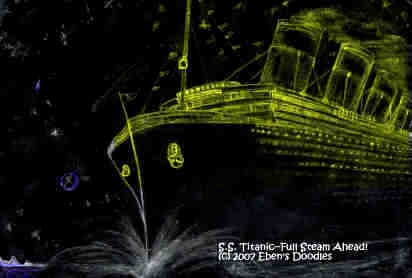

Convergence, at 41 46 N, Longitude 50 14W--the first public warning of what the visitor had in store for the planet it identified as MGY. March 4. Humboldt Glacier calved; this time she dropped not one iceberg but hundreds into the inferno below of heaving waves that was Kane Basin. It was the start of the annual migration to the mid Atlantic. By April the pack ice reached the North Atlantic and moved swiftly in the Labrador Current toward the busiest sea lanes of world commerce. At the head moved an iceberg spattered with bits of Inuk clothing. April 10, 1912, black smoke unfurled from the maiden liner's stacks like huge crepe banners. The flagship of the White Star line's triad of giant steamships sailed commercially for the first time on the run to New York City from Southampton, England, with Edward J. Smith as captain and three bands playing American ragtime and various classical pieces almost non-stop. Veteran seaman with forty three years experience commanding many a big and fine passenger transporting steamer, he planned to retire after the latest new liner's docking in New York. Smith gained the post because of his magisterial bearing as a skipper and his popularity with the rich and famous. His last voyage had all the signs and promise of providing the golden climax of what many people who knew him considered an outstanding career at sea. A captain is only as good as his crew, of course. But Captain Smith was assisted by the best, skimmed from other White Star liners. First Officer William M. Murdoch was typical. So was Fifth Officer Lowe. The ship's architect, Mr. Andrews, also was on board, checking on every detail, and taking notes. Then there was the wireless shack with two radio telegraph operators--what could be more up to date than that? They had instant communication with all ships at sea and even with points on land along the coasts that had Marconi wireless installations. The rather daring Harold Bride (who sported the rather daring habit of cigarette smoking as a gentleman's right even while on duty) was adept at this newest invention that had revolutionized naval communications and sea commerce

That was not exactly a good omen for a maiden voyage, but Murdoch was one officer who looked at the close mishap from a purely technical angle. As soon as he had a few minutes, he went to his officer's training books and also some Harland and Wolff manuals. They would give him the dope, he thought, on the appalling difficulty he had witnessed in turning the giant steamer.

He was disappointed when his books identified no such problem under the heading, “Possible Exigencies At Sea and Suggested Strategical Maneuvers for the Gentleman Mariner.” Captain Smith's order, he knew, had only made the collision at Southampton more certain. They had escaped by a hair's breadth. Fortunately, he was not at a total loss when the books let him down. Having been interested enough to do his own research at officer's school, he knew a bit about design and the dynamics of water flow around a vessel. Even if this ship was of a size and displacement unequaled by any other, surely the same laws would apply. In that case, reversing the engines and turning the rudder would cancel each other out, because turbulence of the water going one direction, from port to aft, and then being forced by the screws in the opposite direction, had to confound the rudder, thereby rendering the ship dangerously dead in the water!

It had happened at Southampton, so it could happen anywhere. He decided it was something to keep in mind if they ever again got in a tight spot.

Should he tell old Smith? Of course! It was his duty as officer and gentleman. And the safety of the ship might depend upon it, he decided.

That conclusion he soon found was presumption on his part, and he realized he should have thought twice about calling a captain's judgment into question.

"An interesting theory, Murdoch," replied Captain Smith, his eyes taking a ceramic glaze. "Some time when you find the opportunity you might go into deeper detail. Now if you'll excuse me, the Henry Sleeper Harpers have requested I stop by their private promenade deck for tea."

The ship made brief stops at Cherbourg, France, and Queenstown, Ireland, for passengers and mail. Then she steamed past the Isle of Man through the Irish straits toward the open Atlantic with 2,227 passengers and crew.

Who could disagree with the likes of Captain Smith?

The radioman, still waiting for Cape Race to sign in, received yet another warning, from the American steam yacht Mary Celeste Avenger.

It came from a Captain William Richard Keith Tibbs MacAdoo, retired Standard Oil executive from Baltimore, Maryland. He described himself as an amateur oceanographer. He said he was in the area "looking for strange phenomena of the sea" after researching various, old northern tales of monster sea serpents gulping down whole fishing boats and crews. He too was told to kindly shut up since Phillips was waiting for a more important message.

At 10:45, in C-51 in First Class, five year old Miss Susan Lucile Carter woke up with a start, her eyes wide-eyed. Her mother’s maid, keeping watching by the child’s bedside (she wasn’t feeling well at dinner and was sent to bed), looked up.

“Now dear, you go right back to sleep...”

Susan Lucile stared at the maid’s face, and began to mouth words that made no sense to the maid. “Daddy’s new car--sinking! Got’s water in it! I see little Susan Lucile getting into a boat with her mama, but her daddy and her nurse can’t. Then dolls, so many dolls, in the water, making a big, big circle, dolls in a circle--and you--YOU!”

Now the little girl had dreamed, her stomach upset by a rich, chocolate-laced, creamed rice pudding, perhaps, at dinner.

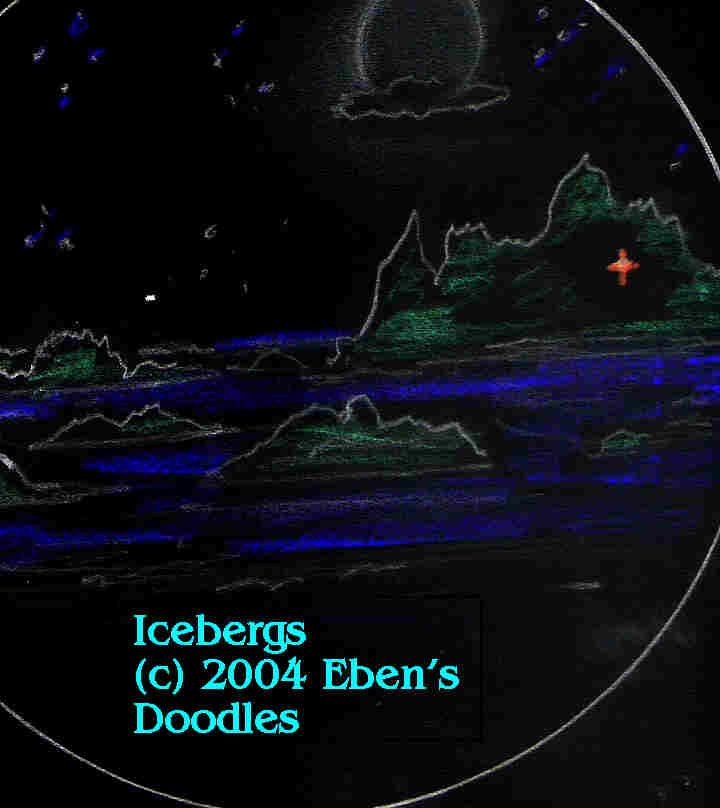

At 11:15, the Mary Celeste Avenger was cruising slowly toward the pack ice that rimmed the horizon. The liner he had contacted was in sight, approaching from the east and a little north of the yacht. Watching for icebergs, Captain MacAdoo was not disappointed. There was a group of at least a dozen ugly brutes visible at the head of the floe as he came nearer the ice. Currents were sweeping them directly south across the very sea lane the British-American ship was in.

Still watching, Captain MacAdoo saw the bergs pass completely over the sea lane and he thought then the greatest danger ended. Any ship as large as the one he could see coming might easily sweep aside smaller drifting floes and even larger growlers without significant damage.

But then he saw the icebergs had stopped. They weren't getting smaller to his view, so he knew his eyes were not playing tricks, even though one leg, damaged in a mishap at sea, was an inch shorter, affecting his vision so that the whole world seemed to list to one side.

The two men watched for that to happen, but the ice remained right where it was. They could see the British liner as well, filling the east with unbelievably vast bow and billowing stacks. She would be passing by very soon, perhaps in about five or ten minutes.

Captain MacAdoo seized a small telescope and scanned the ice more closely. He had no trouble making out individual bergs and the dark waters gleaming like wolf eyes in the channels between razor-sharp flanks. It was a good thing for the liner the worst had already passed over and cleared the sea lane.

"What the deuce?" he said, fascinated. “Gad, this is even better than monster sea serpents!”

As he watched, the largest of the icebergs was moving again. It grew larger in his view, not smaller as it was supposed to do. It was proceeding northward, against the current!

Somehow one of the icebergs had detached itself from the river of ice. Against the prevailing ocean stream, it headed to intercept the oncoming ship.

Captain MacAdoo got on the wireless set and flashed out a second warning to the liner:

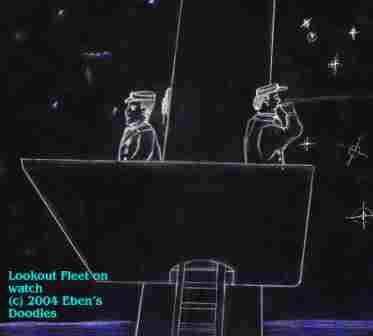

At 1l:40 p.m., high in the ship's crow's nest in the foremast on a clear night, Lookout Frederick Fleet did his duty but struggled with the sheer boredom of night duty on a perfectly synchronized voyage from Point A to Point Z. On the other side of the mast, protected from the chill wind, Reginald his fellow lookout took a leisurely smoke while on unofficial break.

A second or two more passed, then more ice, ship-high, came into view.

It was clearly a large iceberg, but it lay southwest of the sea lane and the ship's set course and so he saw no reason to be alarmed.

Then he saw a lighted vessel beyond the berg. A small steamer of some kind, she moved rapidly as if to overtake it.

His eyes widened. The pursuing craft was growing larger, but so was the iceberg, which now revealed the vast dimensions of white cliffs and peaks--clearly set off by the bright moon and stars.

What was that? he wondered. He thought he saw a needle-sharp flash come directly from the iceberg and touch somewhere at the bow and forepeak before angling down toward the keel.

Completely forgetting his fellow lookout, who was still enjoying an illicit cigarette, Fleet grabbed the mast telephone.

First Officer on the bridge William M. Murdoch answered.

Stiffly correct with superiors, he could be uncommonly breezy and chatty with underlings.

"Willie Murdoch here. How goes it up there, Freddie boy? Cold enough for you?"

"I've got something quite odd going on in view," interjected the lookout, foregoing the usual chitchat.

Iceberg, with attendant steamer, both closed rapidly on the liner with every passing moment.

"It could mean trouble. I see a booming, big iceberg off to the southwest, but it's approaching us, sir."

"You better have your eyes checked when we get to New York!" laughed the First Officer. "Couldn't be coming against the current, my dear boy!"

"But it is!" protested the lookout. He was getting badly flustered, and his voice broke into a choir boy's falsetto under the strain. "It's coming at us, I swear! From the southwest! And there's a small steamer in its wake."

A crackling pause on the other end. Murdoch, in his response, was no longer laughing.

"Has the other vessel contacted us?"

"I don't know. Phillips. He's still on duty tonight."

The First Officer rang off, then called the Marconi shack on A-Deck.

Phillips related the three American alerts, one by the Californian, the others by an "insignificant, meddling trawler or tramp steamer, Mary Celeste Avenger, that’s looking for bloody sea monsters to study!”

"Well, I haven't heard of it until now!" huffed the First Officer. "And what did you do?"

"Sent them to Lord Douglass Ismay and Captain Smith, sir."

"Oh, all right. Sorry."

"Is there a problem, sir?"

"Oh, no. No problem at all. Carry on, Phillips."

The First Officer called up Lookout Fleet, just to set him at ease.

"Nothing to worry about, Freddie. We were already alerted and our superiors thought it not worth our while to change course, or I would have heard about it from Smith or Lord Ismay."

The lookout was speechless. He could not believe his ears, nor his eyes. He was at that moment watching the biggest hunk of ice he had ever seen up close veer right into the ship's path.

"That should relieve your mind, don't you agree?" prompted the First Officer. "Have you thought about what you'll do when we get to the bright lights of New York, my dear boy?"

By instinct the lookout's hand shot toward the bell over his head. He rang it with all his might, three times, then three more times, startling Reginald so much he dropped his cigarette.

The bell clanged out Iceberg! Iceberg! Iceberg!

And Frederick Fleet shouted into the mast phone: "Iceberg right ahead!"

There was no argument from the bridge this time. No lookout in his right mind would ring the bell repeatedly to stop the world's greatest liner who wasn't absolutely sure disaster loomed.

Critical seconds passed while the shocked Murdoch, by telegraph handle, disengaged and then reversed the giant engines and propeller screws. Then he ordered the wheelman turn hard aport. Forty six thousand tons of ship and an equally gigantic mountain of ice swiftly, agonizingly, converged within a stone's throw of Latitude 41 46 N, Longitude 50 14 W.

"This bloody well isn't working!" thought Murdoch, an icy fist of doom squeezing his heart to a stop. "No, not another bloody Southampton!"

Murdoch, at that instant, realized he had no choice. He must lay his career on the line and do what he knew could save the ship.

He seized the telegraph handle and signaled "full speed aport" to the engine room men, who were certain now they all had gone daft as Mad Hatters up on the bridge.

The monster ship turned at the last moment. Instead of ramming the iceberg, she cleared it on the starboard side by the length of two or three hundred yards.

Since the night was so clear, First Class passengers could have seen the iceberg in passing. Those who did were not alarmed by its rather close proximity. They viewed it as another novelty to entertain them on their voyage. A brass polish manufacturer from Liverpool went for ice for his nightcap highball and was disappointed when he found not a cube's worth. He put down his glass to retrieve a cigar he dropped, then promptly forgot his glass and went back in the saloon. Because it was so cold out, and most passengers had retired, very few had caught a glimpse of the iceberg as it slid into the wake of the ship and slipped into the night. And no one saw the smaller craft as it paused to see if there were any damage to the ship's hull to report.

Murdoch, as soon as possible, got Phillips to contact the Mary Celeste Avenger.

But the ship's name seemed a trifle in the circumstances.

Before the captain could respond, the little boat bobbing far below the vast, black, light-spangled starboard side telegraphed again.

Meantime, First Officer Murdoch took a deep draught of black coffee. Despite his exterior steel, his nerves were not in the best shape after the recent events. Worse, he knew he might have the devil to pay for his latest “strategical maneuver.” Captain Smith...

Lookout Fleet called the First Officer. By this time Reginald realized something was going on that required his attention, and he stood with his fellow lookout, his mouth agape.

"What is it now?" answered Murdoch with an annoyed tone.

"Sir, the bloody iceberg. It is traveling north now. But it's doing something as strange as anything it's done so far--it's attracting the ice in the area, like some kind of giant magnet. I can see it's pulling the ice ahead around to the north. It must be drawing millions of tons of pack ice."

"By George and the white dragon!" exploded the First Officer. "Have you gone daft up there? Who’s your relief?"

At that moment the captain burst onto the bridge. His First Class, walnut-lined stateroom was on A-Deck next to the wheelhouse and so he might have seen the iceberg go by. Perhaps, the little incident at Southampton had affected his composure more than he let on initially to his first officer, for he came so quickly that he was not properly dressed. He was wearing lime green satin slippers and a matching satin dressing gown over his half-assembled uniform.

"What, have we hit anything, Mr. Murdoch?" he said, pausing to get his breath.

Murdoch looked at him with embarrassment and a twinge of guilt, as he hadn't meant to alarm his superior into coming on duty in less than proper dress. He was also concerned with the question of his career at sea.

Should he come out with it? The whole truth? And if he didn’t, officers’ quarters leaked like sieves and he knew somebody else would spill it soon enough.

The First Officer, eyes shining with moisture, sighed deeply and played the man of duty and fair play, which meant telling the absolute truth.

"I don't believe so, sir. But we had a rather close brush with some ice a bit ago. I hard-a-starboarded and reversed the engines, and I was going to hard-a-port around it, as is the custom, but she was too close. So taking a cue from what happened at Southampton, I countermanded the reversal of the engines. Nothing's happened to the ship. Only the lookout last reported some freakish behavior out there, that the iceberg is moving north against the current, of all things!"

Murdoch thought that the captain might possibly find the lookout's hallucination amusing and thus be diverted from his own unavoidable slighting of the captain’s performance at Southampton, but all he got was the abstracted, glassy stare that said Captain Smith was somewhere else these days than on the bridge of his ship.

"Carry on, Mr. Murdoch," said Captain Smith to the second-in-command, his hand suppressing a yawn. "If you will excuse me, I believe I will turn in now."

The First Officer was vastly relieved but yet annoyed it had been too easy. He wiped his perspiring neck and forehead with his handkerchief and shook his head as the old man left the bridge.

"A year or two from now," reflected Murdoch, "he'll be just another doddering old pensioner at Biarritz or Brighton, tapping his way with a cane on his daily constitutional. Who then would even imagine that he once commanded the world’s greatest ship and was not some superannuated butler on holiday?"

Nevertheless, the First Officer’s less than enthusiastic appraisal of his superior did not run deep. Truth was, Murdoch had just begun to make a mark and had his whole career to look out for. He was very, very grateful he had passed through the crisis without so much as a scratch.

As for the greater non-event of the averted convergence, hardly any passengers were aware of what Murdoch described to his captain as a "close brush." Those who did glimpse a wall of ice rushing past their porthole windows could hardly take it seriously. At that point few imagined the only ship ever called unsinkable could be....