Saying nothing about the tickets in his pocket, Dr. Pikkard barked orders for a new project which wasn't connected with his usual researches at all, or so it seemed to Pieter, who felt relieved. He was given a job big enough for any Dutchman, and the fact it seemed absolutely meaningless made it all the more attractive to Pieter for some reason.

"Pieter, be so good as to find and collect all old newspaper issues dating back to 2170 A.D. that mention either the so-called 'Greek disease," as it was known in earlier times, or, more latterly, the "English disease,' as we so foolishly call it. From a previous study, I've already determined late 2170 as the year the thing reached flashpoint and came to public attention. Of course, we know it isn't disease at all in the conventional sense, but try to change people's views on that now! Anyway, take as little time as possible doing it! We need to wrap up this little project as soon as possible.”

Anne started to interrupt, but the professor cut her off, and she left in a huff as he continued speaking to Pieter. “You might start with back issues of the New Amsterdam, William of Orange Journal, North River Patrooner, Brooklyn Burgomeister, Minutes, Business, Moral Draughts, and Public Pronouncements of the Metropolitan Council of the Honorable Schlepens (M.B.D.P.M.C.S), Plain Dutch Life, Royal Netherlands States-General Acts in Review, Dutch Duty, Workman's Day and any others you come across.

Those publications will take you back over a century at least. Before that you’ll have to look at papers of defunct newspaper companies, and certain buildings in the Old City are full of such in their basements--sometimes bound up in books. Articles that mention the disease must also report a meteor shower. If they do not, I don't wish to see them. Report back to me if you have a problem. And, mind you, I don't want anybody knowing what we're doing. Let them think what they want. They'd never guess right in a million years anyway if we are the least bit discreet."

Pieter paused to study his employer a moment. What did he meant by "they"? He was more than a little annoyed, for since the finding of the Mary Celeste Avenger he had grown sensitive to mysterious hints of that kind--which, moreover, were becoming more and more frequent. Looking through papers was one thing, but now the professor was getting entirely too mysterious!

The professor took a few rumpled thousand dollar banknotes from his pocket, adding one from yet another--then stuffed them back and tossed Pieter his bankbook instead. "You've shown commendable progress in basic mathematics. You might as well start using this. You are hereby empowered to write the draughts. And try and balance it if you can. I don't have time anymore for it, and dear Anne has to divide her time between two places and seems to have no more head for money accounting than I do!"

Pieter felt of the bankbook, his eyes silently protesting as he considered the great responsibility being thrown his way. He was about to ask his employer to reconsider the fact he only went as far as the fourth grade when the professor, anticipating him, waved aside the objection.

"Stuff and nonsense! You'll do just fine, my boy! I can't thank you enough for relieving me of the infernal bother. Since it worries you, just made sure a little less goes out than comes in. You'll need to sign the cheques to get cash from the hotel purser or the bank to pay expenses accruing to your present project and whatever help you need with the transport. I want you, however, to do the final sortings. Then bring the result to the office."

"But Meinheer--"

It was no use to protest. The professor was certain Pieter had a flair for financial accounting simply because he liked the precision and logic of geometry and calculus. The professor then scribbled and signed a note to the hotel purser and the bank, which Pieter his reluctant new accountant was to show as his introduction to the world of considerable if not high finance.

As for the newspaper collating work, as he got busy the task no longer seemed utter nonsense but merely an odd assignment, even from the ingenious professor. Was he planning on catching up on old news they missed while ballooning and bathyscaphing? With a shake of the head, Pieter couldn't stop to talk now, and he passed the glum Anne in the hall and went to work immediately. Anne threw her cloche at a cat and stalked off.

The new doorman tipped his hat as Pieter went out. Because it was the Royal Wilhelmina and he couldn't avoid the custom, Pieter gave him a penny for his trouble. Being assistant to a gentleman-scientist had certain drawbacks.

"Thank you and good day to you, Meinheer!" said Ernesto Woggham’s replacement, pocketing the money. Woggham had been thrown out of his fine job. He had offended because of poor English and boorish behavior while serving important, English clientele, the Clarkes, come to see about latest investments. He had also refused admittance to British aristocrats' personal maids and valets who showed up black or brown-skinned. The doorman demanded they use the back entrance for freight deliveries since they weren't obviously Dutch, and the servants had complained to their lords and mistresses.

For these infractions, he was let go. But he followed up with worse offenses--resisting, and, more foolishly, resisting the person with the Rooseveltian staurolite fob! Born to lose life’s major battles, Woggham stood up to Hotel Manager Duckering-Puckett and, flinging spit through his bad teeth, utterly refused to leave his glorious post.

When he wouldn't give up his uniform, two Pinkertons held him and pulled off his pin-striped hotel trousers. But Woggham, seeing his chance when they let go of him for a moment, scrambled to his feet and ran for his life, the Pinkertons following on foot. But Woggham got away, losing them in a poor district of alleys and twisting canals. The hotel never did get his splendid swallowtail coat back.

He was put on a very black list, indeed. Never again would he serve in any capacity in any New Amsterdam hotel--if Duckering-Puckett had anything to with it!

So, seeing two tattered, stained swallowtails of someone rooting head down in a trash can behind the Wilhelmina's kitchens, Pieter hired Woggham on the spot, despite the row Duckering-Puckett might make to his employer. No one else would have done what Pieter did so easily. He really believed that everyone had a good heart if you delved and dug deep enough. Helping a person like Woggham was, to Pieter’s mind, something a good person did. You didn’t think twice about it.

Under Pieter's supervision, Woggham, seemingly overjoyed to find employment of any kind, even if it came from a despised class of country boy, gladly carted many wheelbarrow loads of old newspapers from basement archives of the various newspaper offices in town.

Then there was the loading of a hired truck. After that he unloaded at a small warehouse the professor had rented for the project. Editors were only to glad to get rid of molding, centuries-old accumulations of long defunct newspapers predating their own productions. In most cases, it wasn't so much age but the "English disease" that was responsible for their rotten condition. The latest issues most often solidified into solid blocks of cellulose. They crumbled when he tried to pry them apart and gave off a burnt aroma. Strangely, the older the papers the better the condition.

"Bring your truck and clear the whole dirty lot out!" the publisher of the New Amsterdam offered. And Pieter could see he was serious, so he had Woggham deliver several roomfuls of papers to the warehouse.

Pieter, after paying the forever ex-doorman off and saying he might be needing him again sometime, got down to even harder work. Sorting by Greek and also English disease year was easy, now he had to read and pick out for the professor's scrutiny only those editions that mentioned meteor showers and a concurrent rash of mechanical breakdowns in the same issue.

Pieter was surprised how many there were that mentioned the disease, but he could not find a single case of a meteor shower in the same issue. Was this a fool’s goose chase? If so, the professor was throwing his money away again!

He filled box after box with unwanted issues as well as solid chunks of newspapers, and to get rid of them dumped them out the third story window down into the convenient canal. The longer he worked, the more his fingers and face became smudged with black ink like any printer's devil. Soon his shirt and pants darkened with dust and hundred- year-old cobwebs, but he still failed to turn up what the professor had requested. Growing frustrated, as filthy as the grauw in the gutters of New Amsterdam, Pieter decided he had finally earned his good wages and Anne's excellent lunches. Finally, with still mountains of papers all round to go through and not one issue he could show his employer, he quit and returned to the office.

Dr. Pikkard said nothing after hearing Pieter out.

“It’s a’chasin’ the goose when he got himself eaten hours before we missed him, sir! We can look in every place where he could be, but that ain’t going to do him up from the grave, not one honker of him!”

Absorbing this piece of rural sagacity, the professor eased back in his chair and scratched his head. Then he jumped up and started pacing. As he often did with difficult questions, he went over to Icarus and in a low voice Pieter could not hear seemed to consult with the creature. The bird cocked its head first one way and then the other, looking its most intelligent . Suddenly, he started chirping a blue streak, only to stop abruptly and again cock its head while eyeing the professor.

"Of course!" the scientist exclaimed. "Thanks ever so much, my friend! What an intellect! I can't imagine why I didn't think of it before!" The professor strolled leisurely back to his desk and made himself comfortable in his chair, his feet up on his paperwork for his latest prime. "My brilliant consultant has saved you, my boy, a lot of fuss and botheration. I have to agree with him that we took a wrong tack. The reason you did not find the two events listed together is that they did not occur together. In fact, meteor showers, when they did happen, transpired 'randomly,' if I may use that word for our purposes. I have always respected my faculty of intuition, however, and I still hold to there being a true and verifiable connection. But, if you follow me, we need not prove any such thing. Proving it would be a waste of our valuable time and your valuable patience. What we really need to seek out is not proof so much as the 'party of the first part.' You see, we have been missing the point by going after the 'party of the second part'--our so-called 'meteor shower'. But, dear boy, do you follow me?"

Since all this had been delivered in the professor's most excited manner at his rapid, clipped pace, Pieter shook his head.

The professor chuckled. "Well, you'll have time to catch up later. Now it's off to catch the 'party of the first part'. The only hitch is, I haven't the slightest clue as to who or what we should look for. We only have the results of the beast, not the cause. All we know--which is more than--perhaps our little fount of wisdom, our feathered Erasmus--I ought to have named him that instead of Icarus--can break this impasse."

Pieter was too used to his employer's obtuse and whimsical ways to show any expression when the professor again flew to Icarus for another intense but private "consultation." From a goose to a sparrow, it meant little difference in his mind. Icarus again irrupted and the professor acted as though he had got his answer once more.

"Pieter, I'm afraid you're going back to the coal mines--from the looks of you! What we must look for are issues before 2170. The results follow 2170, whereas the cause or causes are necessarily operative before that year. Take a fifty year period. That ought to be sufficient. We have very little historical record of what happened around 2150--there wasn't much of any value written down then--but that need not concern you--any papers you find may tell you something."

This was just too much to swallow--the plain Dutchman revolted at the sheer nonsense of it all.

"Impossible, Meinheer!"

"Oh, is it? Well, the track we are following apparently goes back to 2170. What if we could go backwards, to a time just before 2170, which is the beginning of the track? Wouldn't we then capture the bird?

Pieter thought about it slowly. He thought it impossible, of course, but he didn't like to be wrong. His first brush with the professor’s “before and after” had not been encouraging. But then he had often seen V-formations of Canada geese heading south from summer nesting grounds just north of New Alkmaar and the canal, though he could not be sure what they were doing before they began to fly. They could have been swimming, walking, flying, doing any number of things in the big swamps and woodlands that made up almost all of New Amsterdam. And they could have been doing any of those things in no end of different provinces. To track a certain bird down by the professor's method would be impossible. No, let the professor have his “before and after” back! he decided.

"Meinheer, I don't know."

The professor, even more gently than the first time, begged to differ in a low, dry as dust voice.

"Egad! Are you an absolute dunce? Marshal your Dutch wits, boy! Do you have molasses and cement in that skull of yours, or good Dutch brains? After all I've tried to pound into your wooden head. Sometimes I think it's useless, a sheer waste of my valuable time! Oh, heavens, give me patience! Such stubborn idiocy will be the death of me yet! Don't be so stuck in the past! But, to go on, I would say we certainly can take the bird in hand sometime before the terminal year of 2170. What do you say to that? I suppose you have no idea how? Do you? Do you? Well, say something! Use your brain, dumkopf!"

Pieter, on his part, was beginning to look like the time he faced off with Horst over the kick in the pants. There was nothing wrong with his head that he knew. He could butt a top back on a barrel with it and not blink an eye. Utterly bemused by this time, the still pragmatic Pieter showed himself out. He really did feel like the things the professor had called him--though he'd never let him call him those things again and get away with it. But what was he to do? His job demanded he do something for his good wages.

Hours later, he was just sitting in the warehouse, a gas light burning over the scene of his utter despair. He had no idea how to find the "bird," the maker of the tracks. Nevertheless, as he sat there without hope, he continued to think about the bird tracks. Then he thought about the bird itself. Birds, he knew, came from eggs, and they had to be hatched. What evidence was there when a bird was hatching out anyway? Cracks in an egg! That kind of thinking, for Pieter, worked better than the professor’s confusing explanation.

He set to work, and before long he began to get excited when he started tracing the cracks, discarding some, while retaining others that showed more promise. Eventually, lo and behold, the most promising cracks converged more and more and ultimately led to one great Pre-Hollandian egg called Marcus M. Chillingsworth. There was simply no other egg so great as his. A marquis dubbed by some ancient Swedish king, a Nobel laureate, government leader, author of a series of highly-acclaimed books about pre-”World Union” politics in the corridors of power inside 10 Downing Street and Parliament, and renowned scientist, his name turned up most often.

And his name, interestingly, began appearing frequently around 2150 in connection with the founding of something called the "World Union." A Union of the whole world? He had never heard of such a thing. He seemed to have a lot of trouble with things blowing up on him. He rode in strange aircraft called a "domecraft." He visited many cities, which also began blowing up all around him. He got awards of various kinds.

A seventy two year old Duchess of Milford Haven had suffered a broken arm and nose at Athens at one of the awards presentations. He was married to an Allegra Samantha Jones, former art institute student.

He gathered most all the world's gold reserves in one spot, a bank in London. There were announcements of the births of three children. And, strangest of all, when he retired to live in London he still ruled over a Swedish island called Gothenberg somewhere far to the north. Was he the bird? Evidently, Chillingsworth was a very important egg of a person, to receive so much of the world's attention. He was glad he could let the professor decide.

Now that his researches had found a focus, Pieter soon had other things than dirty old newspapers to occupy his time. Having neglected Anne so long, he wished to make it up to her.

He finished the huge paper project, submitted the gleanings to the professor to read and tabulate, and was told to take a hot bath and get some fresh air.

The warehouse could be tidied up later and returned to its owner once the whole process was finished, he was told.

"And pour on plenty good Dutch suds and hot water and use the wire scrub brush like a good boy!" the professor said, sternly eyeing Pieter though he wouldn't think of inflicting the same torture on himself. "Your hair used to be tow, if I remember right. We can't have you coming on these ostensibly royal premises looking like you sweep chimneys for a living! Duckering-Puckett and the Wilhelmina owners are beginning to making some ominous noises about the upcoming renewal of my lease!

He says guests are beginning to complain of my scientific activities, which are not really “conducive to the normal operation of a hotel,’ in his opinion.

I said I would seriously consider buying the hotel, if that would help the situation any. He thought not.

Thanks to his position at the hotel, having discreet ‘connections’ with the gentleme

n of the West India Company, he released to me the private, most delicate morsel of information that this hotel is the property of the West India Company, then assured me the Company would never sell to anyone but a fully registered, affliliated shipping magnate and merchantman. I could have told him my late father once sat on the Board, but that would have flattened the poor man. Best to keep silence before fools and suffer them!"

Anne had endured a long wait. No one could have disagreed with that. As usual, she was pacing back and forth when he stepped out of the suite. "Oh, I know how busy you've been, but you don't think how difficult it is for me," she said, eyes glinting with barely suppressed fire.

But he did think about it! He knewl she could not follow the itinerant pair about the whole of Holland America, and it was impossible when they took off for the stratosphere or dove to Davy Van Jones' Locker. Also, she could not manage transatlantic trips on the stipend the Professor allotted her every month for helping about the office. Normally, all she could do was wait at the office for his time off. Yet he was never really comfortable about her hanging about for him. He had his job (and avoiding Van Tootle-Clarkes's) to think about, didn't he? Any fellow would understand, but her?

"Pieter, all I've got when you're gone is these poor old fleabags of Oom's!"

It was obvious to Pieter that Anne could not be put off one minute longer. He followed her out and they started walking in a town that seldom now lived up to its old reputation for romance and young lovers. Fortunately, the weather was still good, not too cold as yet though last year at this time the North and East River, even the upper bay, had frozen solid, so that "Staten" Islanders took sleigh-cabs to work in town.

His machine-made braces and artificial limbs working much more efficiently than his former homespun contraptions, Pieter could manage a long walk with Anne to straighten things out. They walked slowly into the street and turned first one way and the other. New Amsterdam, with all its eccentric twists of canal and street, could look picturesque enough at certain moments when the light was just right, though most of the time it was indescribably ugly, with all the beggars, unemployed, baton-wielding constables, and litter. Also, the city itself was shrinking in population and industry. It lost more people than it took in, despite energetic little colonies of Italian, French, and Spanish refugees sprouting like mushrooms on the American side of the Atlantic since Europe had begun to fail and collapse in dead earnest.

They came to imposing walls and the pillared entrance of old and highly revered Van Butler Library of the University of Amsterdam--one of the buildings of ancient America that had survived to the modern era. Etched in the stone facade were the names (with the “van” added later) of the greatest Dutch geniuses of the Golden Age--Homer, Herodotus, Sophocles, Plato, Aristotle, Demosthenes, Circero, Virgil, and one that read only "Chil--" because it had suffered defacement by vandals or the dread English disease.

They stopped to look up at the names and the inscription of four words cut in stone beneath it. Anne, having been tutored in Latin, tossed off a translation for Pieter’s sake..

“I can translate that! It simply means ‘gallop like a wild horse, please open the door of the broom closet,’ no, ‘racing down the track...straightway....for the.....grass clippings?....no.....boxes of sleeping lamppoles!...no....truth!, something like that in Latin, a language you wouldn’t know.”

"Latin?" he asked. "What is Latin? Is it the same thing as 'nova' or 'supernova'?"

Anne giggled. "My, you are from up country! I’d think you’d know by now, being with the professor every hour of the day for weeks on end! Well, Latin is a famous old dead language they use on public buildings and monuments and books on science. And, no, a nova is an exploding star. Oom can tell you all about it. We didn't keep our science tutor long enough to learn much of anything. At the time my sister and I were doing an experiment with highly explosive chemicals and--"

But Dr. Pikkard already had explained the matter sufficiently. Exploding stars meant nothing to a plain Dutch boy, since there was no possibility of one within his experience. Rather, the Latin, even if Anne's description was lost on him, was impressive and noble-looking. Stone-cut letters seemed to him to contain everything a plain Dutch could want--solidity, compactness, brevity, forcefulness, and plainness. Beside Latin, all else seemed Jack Dutch thistledown and tomfoolery.

His yearning for a world where such things ruled and held undisputed sway came out in a hushed, reverential, shy voice. "I plan to attend such a place as this someday and get training like the professor," he confided with a glowing face to Anne, over-looking for the moment that she knew Latin and he did not. As for becoming an ship engineer or ship architect, well, that was best kept secret. She might think he was exceeding his capabilities, which he had lately come to see were greater than anything he had formerly thought.

"I hope not," laughed Anne with a sharpness to her laugh that was like a slap of cold water, dashing him with reality. "You really don't know what you're getting into with these people. They are the ones that hate Oom and are always undercutting him every chance they get! You'd be better off just sticking to your job with my uncle and learning what you can from him and his books."

Pieter, still entranced with the spell of the noble Latin inscription, wanted to take a look inside.

"You really aren’t thinking of going in, are you?” Anne challenged him. "It's no place for Dr. Pikkard's niece. They might eat me for dinner, and you too, if they’re really hungry!"

Pieter left Anne on the steps and went in. He had got no more than a few steps inside the entrance hall when robed men converged on him, one standing behind the other. Quickly, several other librarians with the same dark robes and cowls over their heads were approaching them too. Never had he seen anyone dressed like that--but, then, he had never been in a modern university.

"Hey, cripple. Show your card!" demanded the first. "Are you a registered student? I think not!"

Pieter, feeling the insult, bridled. Who were they, after all, compared with a future ship architect-engineer?

Another man, distinguished looking with a long gray beard, stepped forward and gave Pieter a gracious smile. "Never mind my rude assistant! He needs to mind his tongue when visitors call. You're Dr. Pikkard's assistant, aren't you? We've been hoping you would stop by. Is there a particular subject you are interested in taking? Perhaps we can be of help. I happen to be the Registrar of this noble university."

When Pieter came back out, Anne stared at him with amazement. "You mean they didn't throw you out? I can’t believe it. I’ve actually seen people come tumbling down these very steps!"

On the contrary, they had invited him to return any time he wished to look at the library of books about mathematics. He had been assured that they would be happy to take his application for matriculation. The gray-bearded gentleman, a full professor in the office of registrar, could not have been more encouraging to an up country boy like Pieter. He also expressed his great regret that relations were not as good as they should be between the university and Pieter's employer, and added that they had done all they could to mend things, but the professor had refused every friendly overture toward reconciliation of their differences. This evidently sincere overture struck a certain chord in his Dutch soul, which touched on the trait his forebears like to cultivate, the ability to bring total opposites together in smiling amity, that is, to make devils and angels dance on the head of the same pin.

Pieter looked back at the library (and his own employer) with new eyes. Instead of frustration, he felt his life had taken a new start to the career of his secret dreams. But he kept the discovery to himself and turned back to Anne.

She, in turn, was watching him closely. "What did they say to you in there? You look like a cat that just swallowed the butcher’s canary!" With a laugh she reached out to touch his shoulder with a friendly pat.

Pieter drew back instantly and stiffened up. He never liked affectionate touches from anyone--especially since his accident.

They started walking again, after an awkward silence.

"I didn’t mean anything by what I said back there," Anne said. "You take everything so personally and keep too much inside and you'll never have any fingernails if you keep biting them like that. It'll all blow up someday if you keep on that way. And you should know something.

I'm sure they recognized you. Anyone associated with my Oom could not escape their notice. But don't take their treatment personal. The one they're really out to get is my poor Oom, who is innocent of anything they hold against him except trying to advance the cause of humanity and human knowledge. The reason why they are so furious is that a couple years ago the university got the authorities involved and a suit was filed to stop his researches. It was going to come to trial, but the professor did not wait to lose the case and have to stop everything he was doing. Without defending himself, which would have been hopeless anyway, he took his balloon up over the city and dropped leaflets announcing a free circus to all of New Amsterdam at Van Coney Island. Fortunately, he had months to prepare and get the whole thing together. It was marvelous.

Of course, I was thought too young to go out unchaperoned, and poor Mama wasn't well enough to go circusing with me, so I sneaked out a window. I never had so much fun in my life.

You ought to have seen about a hundred men trying to shimmy up a greased pole for the roast suckling pig at the top! And the dancing! And the fireworks! Oom went all out and must have spent half his patrimony.

Well, most of the people at the circus heard that the university was taking their benefactor to court on a trumped up charge. The next day was the trial. A huge crowd showed up. Some things were said, a few windows broken, and the police were caught totally unprepared. It didn't take long for the judge to throw out the case so everybody could go home and not cause another nasty riot. After that, the university didn't dare try to stop him in public, but he's still in danger, I think. Maybe worse danger, because they aren't operating any more in the open. Universities, so-called!

They're supposed to increase and preserve knowledge--not bury it! But that is my own opinion. They themselves don't think they're doing anything wrong or contrary to their role as institutions of higher learning--that's how far they've sunk, or society has sunk."

Pieter, hearing Anne's account, didn't know what she was talking about. He hadn't received a rude rebuff at the university--far from it.

In fact, the more she talked the more he questioned what she was saying about the university and the professor-registrar. He might have told her so, that she was wrong about a lot of things like that, but whenever they came to a bench or a spot where they might be able to talk, someone moved in, usually to beg or sell them something.

He might have known that would happen. But because of Dr. Pikkard's initial warning, Pieter still did not feel entirely free to talk to her at the office, so how could he tell her plainly? All he could do was try, in as polite a manner as possible, if an opportunity ever came their way. After all, she was his employer's niece and his employer had made his own wishes clear enough.

"The professor will let me go if I continue on with you this way," he said at last, though keeping all his deepest reservations safely hidden.

"That's poppycock!" she retorted. "Boys, er, my friends are my own Dutch business! Oom would never, never fire you! You don't know, but I called him from the lobby that day you first came. Though I got him to at least give you a hearing, he's had plenty opportunity since to see you're no shiftless bum out of the gutter. He really likes your work and dedication and depend--"

Pieter, though unpleasantly surprised that he owed getting his job to Anne, got over it quickly as he warmed at the thought of his Dutch dependability. Just then New Alkmaar and the mill came to mind, spoiling the moment. He had been dependable there too, but what had it gotten him? He lifted a crutch as a final, clinching argument and the nearest beggar, about to move in on them, changed his mind.

"‘Walking backwards in the street, you bless the good Dutch stones twice that you meet,’" he quoted from an old proverb in a low, contorted voice, his face breaking into a web of worry lines. "I mean, if I had another accident, I wouldn't be any use to him, good-hearted gent that he is! Then where'd I be? Back at the mill for the rest of my life, that's what!"

Anne had no response to his homely wisdom. She had seen the face of Pieter as he might well look as an old man, seventy or eighty years of age, and it wasn't pretty. "Let's go to Van Frick’s"

So they set off for the gallery containing Old Dutch Masters. But she stopped when they were almost there. "No, I don't think you'd like looking at any more Old Masters if you don't like Oom's. Instead, let's go down to Hellgate."

Pieter was really upset now. She had changed her mind again! How anyone could change one's mind was beyond his understanding.

Anne noticed and was put off. “Why can’t you try to be a little more flexible? I’m too flexible, maybe. You’re not enough! If we move toward middle ground, then we ought to be just right, don’t you think?”

Her line of reasoning led to her bursting out in laughter after being peeved with Pieter. He just stood, solemnly observing her the whole time. She sighed as her laughter ended, and they turned in at the East River instead. On a frigid sand beach already half-clogged with ice floes, the screaming gulls swooping for bread crumbs, Anne soon forgot the long, vexing wait at the University that had put her out of sorts with Pieter’s unbending nature, as she saw it. She smiled at him again. “Pieter, we're near the Palace where there’s a matinee. Betti Bangles and Clarence Van Ruthingford are playing in ‘Miracle on 34th Street.’ It’s Dish Day too, and they're giving out Delft Cranberry Ware this time--my favorite, since I hate that ugly old blue stuff they usually dish out! Let’s go!”

Still not about to give up on her outing, Anne thought hard. "Let's go to that nice--" she suddenly blurted out, thinking of a Spanish cafe on Isla de los Estados (old Staten Island). Dolorously called "The Blue Centaur," yet it was famed for gaiety, fine food, Gypsy violinists, and flamenco dancing.

They moved off, Anne tugging at his arm to get him to move a little faster. Even before the crutches, he normally moved slow and sure, like any up country Dutchman. They paid out the price of a cab, penny steamer, dinner and tips, though Anne had to pawn heirloom earrings on the way at a pawnshop. Pieter had to walk out or she would have bought an old painting she happened to pull out of a pile of trash. It was the most outlandish thing he had ever seen after she blew off the dust in a big cloud that made him choke. A train was pictured chugging in full steam out of a fireplace, of all things. “That is no good for your money!” he chided her, starting for the door.

“Wait!” she cried. “It’s a terrific message, if I can only figure it out. Maybe...maybe...yes, it means something like storms make a tree grow stronger, and in the end you get to ride the train to heaven or something pretty good, like those poor Jewish boys in the Fiery Furnace, remember? They took a big risk and it paid off royally. I know that is kinda mixed up, but that’s the meaning--there’s no doubt about it!”

Pieter, blowing steam of his own, pushed out the door and stood until she came out, without the painting. “You win,” was all she said as she took his arm and they continued on.

At the start of this outing she had brought some money, it is true, but Pieter soon noticed that she never estimated her expenses correctly and came up short. But in order to teach her responsibility, after daring to give her a solemn lecture, he steadfastly refused to bail her out time after time. With Pieter, she had to go "English treat" or not go at all--thus the resort to a pawnshop.

Anne, not at all grateful to him, thought she might fly into a rage and give him a lecture in return on his own short-comings. But she thought he would never admit to them, though he fully expected her to admit hers, and all the words in the world would be no use on him. So she let it pass.

Once at the cafe, everyone except a lone plain Dutch boy soon forgot wretched conditions around them in the world. Even a painting of the Blue Centaur, marvelously preserved from the taint of English disease, only served to stimulate the most riotous and flamboyant toasts. There was a standing offer by the management too. Whoever could satisfactorily explain the painting could have his bill written off, no matter what he ordered. Anne tugged Pieter’s arm, who was reluctant to try because it would attract attention to them and perhaps occasion some rude comments.

“What do you think those strange objects in the picture mean?” she prompted him, as they stood gazing upwards at the Blue Centaur with the silver trident, held poised over another Centaur’s breast as a fire blazed against a background of intricately contorted, dark blue rocks. There were some other things in it that no one could explain. A brick, lettered with an odd name most people took for the artist’s--”DUBESOR.”

“Ol’ Du Besor was a great painter maybe, but he must have had one too many when he worked on this pitcher!” laughed a man at the table nearest them.

Anne nudged Pieter. “Cmon! Use your head! What do you think the painting means? If we can come up with a good story, we get a free meal for two! But since you’re the guy on this date, you have to tell them. They won’t listen to me.”

Pieter, even if he didn’t have an imagination, wasn’t interested. He would have liked the free meal, but interpreting a Jack Dutch picture was not something he relished. His lame try didn’t come close, making Anne’s eyes roll up in her head.

His Dutch upbringing showing in odd ways, he kept the combination bed and sitting room neat as a pin except for never dusting behind things or sending out his wash (to save the hotel laundry charge). He also saved soap by wearing his things several days in a row before washing them himself. The only thing he was really fussy about, and dusted regularly, was the useless trifle Leamis had fobbed off on him. It stood on his bureau, cleaned and buffed with a rag until it shone like new.

“Someday I’ll be able to afford the best suite in this hotel!” he thought with pride. Of course, affording and taking were two different things in his world. However rich he became, he’d never, never live up to his income. That would be shamelessly Jack Dutch. and he’d lose everything. Until then his room was conveniently cheap if not fashionable. He never had guests and Anne had popped in only once or twice and then seemed very uncomfortable. Anne had brought a distinct change into his life, now that he thought about it. In New Alkmaar he had turned a few pretty heads before his accident, but paid them no attention. What did he want there with an expensive girl? He had to work and get ahead if he could, and that was that. In New Amsterdam it was different. They could not be avoided, however a fellow tried! Never had he dreamed of such times--Italian and Spanish food, so many places to go and things to see. His head whirled at the thought.

But yet it was too much a game, too much a Jack Dutch thing, and too expensive. It made him feel uneasy and tense. It hit particularly hard in his Dutch pocketbook, his chief objection to good times. How he liked it whenever he regularly emptied his salary under his mattress, a formidable, prison-striped, cob-sawdust-tundra moss-thistledown-stuffed Dutch tick that could have passed for a convict's. That was really the only moment these days when he was really, truly glad he was working for Dr. Pikkard.Whatever his short-comings, he paid well in good Dutch money and the bulge under the mattress was getting rather difficult to sleep on.

When he did fall asleep in his little, drab quarters, he dreamed of dark-robed figures with friendly words and names of unknown great Dutchmen etched in stone, from Van Homer to the unappreciated, foreign, “van-less” "Chil-". Like them he saw himself striding along some bright day, impressively dark-robed, through the great, bright, clean palace of learning. People were bowing down to him, as if he were the splendid sovereign of all the world's royal league of Nether Lands. And Anne? She was also there, standing beneath, wagging her finger at him and shaking her pretty head.

It was a most disturbing dream.

He was suddenly awakened by furious pounding on the door. Leaping from bed, he grabbed his bathrobe and struggled into his shoes, thinking the hotel must be afire. Flinging open the door, he found the professor.

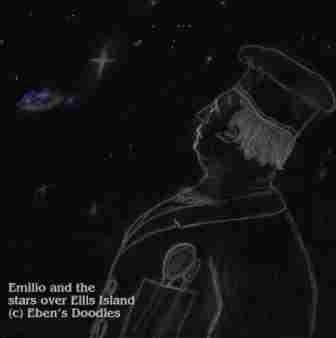

“Sorry, my boy! I’d never think to wake you on any other occasion, but you must come with me immediately and see something I caught in the starscope!”

Pieter groaned inwardly. He was more inclined to want a fire than a chance to look through the professor’s “starscope,” an astronomical instrument he had heard mentioned once or twice but not seen.

Throwing on more clothes, he hurried after the professor, who led him to the stairs (which were quicker than the elevator). Following the professor out on top of the hotel roof, Pieter was dimly aware of the unusual clearness of the sky. For once the clouds had cleared away, which was a rare opportunity for the starscope.

Although there wasn’t much room to maneuver, the steeply pitched hotel roofs had a flat iron-fenced “widows walk” along the top. Stepping round warm, usually smoking chimneys the professor had foresightedly tied asbestos blankets over, they reached the starscope. It set on the longest stretch of widows walk where the professor had several feet on each end for other equipment and a chair or two.

It was, indeed, a rare night. Still, cloudless, though quite chilly, it presented the professor an unusual chance to use his starscope, which he had not missed.

Dr. Pikkard was anxious that Pieter take a look without spending any time on explanation, which could be given while Pieter was looking through the instrument. It took him only a moment to check the setting before motioning to Pieter to begin. It was a large instrument, eight feet long and forty inches in diameter. From the ground it was dwarfed by the big chimneys of the Wilhelmina, but up close Pieter could see it had been a considerable trouble to get it to its present position, unless it had been assembled on the spot.

Sitting down he put his eye up to the viewing glass. It was like looking up through a dark chimney at a patch of open sky, only the great power of the lens brought the stars much closer to him than he had ever seen them in his life.

Impressed by the size and brilliance of the heavens, he was just beginning to wonder if that was all the professor had meant to show him, robbing him of sleep just for a nice spectacle, when he grew aware of something very odd. It brought to mind the dark patch he had seen on a previous evening, but with the starscope he could see it much, much better.

After a few moments, he had had enough and stood up, his legs stiff with cold in just pyjamas.

Eager to hear, the professor would not wait for his response but prompted him. “You saw the thing, didn’t you?”

Pieter shook his head as if he didn’t want to acknowledge what was in the sky, or couldn’t believe his eyes.

The professor suddenly grew grave. “That’s all right. It’s a bit of a shock, I know. I tend to look at things with a scientific eye and forget the personal aspect for the moment. But I realize it isn’t very pretty. I fear I waked you and gave you a sight that will give you nightmares--if you sleep again tonight.”

Pieter went back to bed after that, for it was still in the early morning, and just lay there, as the professor had thought would happen. He kept wondering, what thing could be eating stars whole? Whatever it was, it was gulping them down without a trace being left, so that there was an whole long lane of empty space cut out where there had been apparently uncountable stars shining in the night.

He recalled, too, the professor’s closing remarks: “I have no idea what it is. No known object has cast such an evil spell over the heavens since the fall of Creation. Like black acid eating up everything it touches, it has spilled out from the heart of the Galaxy, destroying everything in its path, and it is heading our way at unimaginable, scientifically impossible speeds. What could it be? I’ve got to find out!”

But Pieter, and the entire hotel, was not to rest very long. Black coal-smoke filled the hotel and soon brought people running about trying to find the fire. Soon, grand ladies with all sort of odd patches on their faces and their hair in strange contraptions were hastily evacuated to the street in mink coats and night gowns. It took some time to trace the cause, but they finally rooted it out. The professor, it seemed, had forgotten the chimney-snuffing blankets.

As for the “Black Shadow” or “Black Cloud” stalking the stars, he said not another word. It was as if it had never happened, and Pieter had to wonder if he had had a bad dream and only imagined seeing a black cloudlike thing eating its way through thick, brilliant clusters of stars and leaving a black, starless swath behind across the entire sky.

With no call on his assistance, Pieter was just in the way, so he was told to get assistance and clean the warehouse and hand back the keys after paying for its use. It took all day doing as ordered. Pieter watched as Woggham took the last box filled with crumbling newspapers out to the canal and dumped them. In need of little cleanup afterwards, Pieter went to the professor’s bath and washed his face and hands and dried them carefully on a towel monogrammed HM Wh in gold thread. Hot water.

Scented soap. What Jack Dutch luxuries! If only he had thought to bring along some good lye soap of his mother's. He hated the kind the hotel provided, so he always used just enough soap and water to do the job and would never draw a full bath just for himself, and the gold threaded monogram especially made him scowl. Like other aspects of his life with Dr. Pikkard, it could not be avoided.

The Wilhelmina and the professor's office were only about a penny steamer away from Anne's. Pieter, though thinking of his future and already building a sizable bank account under his bed mattress, still had no excuse for not visiting Anne when she wasn't at the office feeding the cats.

He slipped out of the hotel where more and more the hotel personnel were treating him with differential bows and curtsies, as though he were something more than an employee because he assisted a North River patroon and a scientist. These, unlike the effete soaps, he accepted.

Now that it was late afternoon, when the shops were beginning to close, Anne, he reckoned, would expect to meet him at her house. Still thinking to make it up to his free-lunch-bringer for past "neglect" he knew couldn't be helped, to save himself a long walk to the docks he hired a taxi after a considerable struggle with his sense of thrift. The paddle-wheeled, steam-propelled canal cab made swift progress even in the most crowded thoroughfares. The taxi, for five cents, would take him straight to a canal in Anne's neighborhood.

Just beyond was the turning onto Rensselaer Avenue with its grand procession of West and East India Company mansions, rich men's follies, lining both sides of a marble-faced stretch of Herrengracht. Though close neighbors, the patrician mansions with their “gentlemen burghers” and the workaday, middle class brownstones were worlds apart in money, culture, and power. Cops on their beat usually let lovers alone if they didn't loiter too long in one spot. It was a treat for young people to leave rows of rather dingy brownstones with their smell of fried potatoes and "Slemp" and a rather dirty canal to wander down the brightly elegant avenue. A stroller could at least look at the rich and powerful and imagine what such a life might be like. Or at least Anne, whose family had once been in a position to enjoy such opulence first-hand, could. Pieter was more of the workaday variety of Dutch and had no such imagination.

He always stopped a block away and walked, careful not to attract the attention of old lady gossips behind the stiff, white, lace curtains. Proving appearances could be deceiving, the Kilpaison domicile where Anne had been born and raised was a modest, three-story brownstone, externally.

Like the Kilpaisons, it had seen better days, but it still kept up appearances better than most of its kind. Anne's invalid mother had died a few years previously from "English gout," they termed her cheery though lingering indisposition. But her grandmother was still hale and hearty in spite of a tiny stroke now and then, and she maintained boxes of valiant geraniums at every window during the painfully brief interlude of summer--snatching them safe indoors at the first hint of frost in mid August.

Anne, knowing her uncle's habits and schedule as well as her own, had counted on Pieter getting the day off. Having worked all day on a surprise for him, she was eager to see his reaction. She was already racing toward Pieter, who at first didn't recognize her as he climbed up to the street from the taxi. Still the plain Dutch youth, though his nice, neat blond Dutch head and Delft blue eyes were handsome enough, Pieter was shocked by Anne's transformation but bit his tongue. The demure little feathered cloche hat was gone. "Where is it?" he blurted out, his face showing shock and anxiety and all the worrywart lines that went with them. "What have you done to yourself?"

He was still staring at her head, and she laughed. "Oh, that nasty, ugly thing. It's lining a mouse cage at home, for I'll never wear mourning clothes again. Once is enough for a lifetime! I'll die first before I go about like that another day! Even if Grandmama kicks the schlemph bowl, I’m wearing red! The color of a naughty, naughty, flaming red rose!"

Also missing was the modest brown sweater and long black skirt combination she favored during the period of grief for her departed mother. He might have understood some pink ribbons added to her favorite little round hat with the feathers, but this? That was farther than a Dutchman would normally choose to go with the vanity of big city fashion.

All he could do was stare as she began to show off her skirts, giving them a flamenco swirl and a flash of the ankle and calf that immediately caused a sensation behind a dozen window curtains.

Obviously, Pieter had yet to learn that the Kilpaisons thought differently than the common run of Dutch. Being what they were, they always had danced to a different drumbeat. Her grandmother helping her, Anne had truly done herself up. She gave up trying to look like she was solid Dutch. To complement her dark looks, she was wearing the most unDutch colors in her mother's old wardrobe. Let every Dutch person passing by cast a reproachful look! She knew she was stunning in Gypsy-colored skirts and silk blouse, her grandmother's magnificent Spanish shawl of black lace providing the crowning touch. A Spanish comb in her hair and long earrings like Saracen scimitars too--if only Pieter would notice!

"You're much too dark a woman with that dusky Jamaican skin even to my eye," her grandmother had advised her earlier that day. "Gracious, an ancestor on your father's side must have tarried too long in the Caribbean! I can imagine what happened! Best not try to cover it, my dear. It won’t cover. Anyway, you're now at the age to blossom out. You'll do best by yourself if you favor the exotic look. So don't be afraid of what people with starch in their skulls think. Be yourself, dear! Use plenty of heavy jewelry and deep reds, purples, violets, maroons, especially maroons--they’ll look right on you, my dusky little rose..."

After a few moments of painful adjustment, while he glanced apprehensively around at the surrounding houses, Pieter had no choice but to go through with the date, even if she were overly-colored and exotic enough to fit, in his mind, at the zoo.

She gave him a tug to hurry him up. "Sure, I look a little different from the other ducks in the pond. That was my intention. Why should I have to look like that Gladdie Gillingham lady and act so mannerly like her? You’ll get over it! Now we’ve got to hurry. Grandmama takes a hot Jamaican rum toddy for her bad toe and goes to bed early, but she wants to take a gander at you before she turns in for the night."

The nearly vertical brownstone steps took some of his breath away, and he had few words anyway, being so surprised when the Kilpaisons mobbed him at the door.

"Cute, but can he smile without having to be poked in the caboose?" observed Anne's youngest sister, nearly eleven, one dark cheek painted with red and white to resemble an ace of hearts playing card. She whispered something more to her confidante rag doll and Anne, overhearing or guessing, aimed a hefty slap at her which her sister ducked.

"Welcome, young man. Don't mind these dashing young ladies and their remarks!" said an amiable, balding gentleman with much too high a collar.

Mr. Kilpaison continued in a shy, almost feminine voice. "I've learned to hire all female tutors. The men run off after the first day! Imagine that! And my daughters are so pretty--perhaps too pretty!"

Pieter looked a little closer at the owner of the remarks and his eyes widened. After greeting Pieter he had brought out glasses and put them on. They were not only outsized, but they were tinted dark green! Noticing Pieter's stare, the father chuckled.

"Oh, these! My eyes were sadly, sadly weakened a few years ago when my dear wife kept me a bit too long down in Jamaica. It was the old family plantation and dairy, gone badly, badly to jungle now. Too much to keep up and the servants and dairymen were always running off to fish or play. Ours was appointed the royal dairy and supplied the palace--so we had to keep producing even without help. When my eyes went one day as, I recall, after reading some rather naughty French magazines, I recall we had to wait a terrible long time for the emperor's milk cart to come, and I had gone I don't know how many times out to the road to look for it when--"

Anne touched her father's cheek, or rather pinched and pulled it this way and that, which looked mean but started him chuckling out of control.

"We don't have time for that story, Papa!" she said to the widower, who seemed merry enough despite the big red mark Anne's fingers had left on his face. "Maybe some other time when all the lost Kilpaison cows come home from old Jamaica and restore the FABULOUS family fortune!"

Leading Pieter, Anne dashed down the hall and looked into several rooms, choked with old plantation furniture and bouquets of dried and fresh flowers, bird cages with parrots and cockatoos perched on top, rabbit hutches with no rabbits but sometimes with lizards or turtles in them, musical instruments and metronomes, an all pink grand piano, game sets of all kinds, stilt poles, skates, fancy painted trunks, ceramic figurines, tin soldier sets, kites, rocking horses, gaily painted Old Country cupboard-style beds, and many more things than Pieter could hope to recognize. Up the stairs they went, high and narrow, at least two floors. Down a twisting squeeze of a hall Anne led him next, popping into a sewing room, then a sitting parlor with a balcony and a hundred pots of geraniums brought in for the winter. She stopped, rubbing her chin just like her uncle. "Hmmm, now where has that nasty, mean old witch--" A surprised look came over her. "Well, I never!"

As if she had forgotten Pieter, she went directly to a door and threw it open. It flew so hard it banged against a huge ceramic vase with peacock feathers and would have knocked it over with a crash but the wall stopped it.

An old woman was standing up from a wicker wheelchair at a billiard table, putting the point of her stick to a ball she had just repositioned for a better strike. Everything in the room was extremely Jack Dutch and odd, even to the book (an alphabetic psaltery of Lamb and Pritchard’s) propped under one table leg that did not quite square with the floor since the time, rather recent, Anne had sawn it in a fit of pique.

"Grandmama!" Anne stormed at her. "You can't take any more of these all-night games, you know that! You'll have another English stroke, and it'll do more than deaden your big toe next time. You've been so good about it the last six months, and now!"

The old lady with a heavily powdered and rouged face, and wearing a low-cut gown and rings on about every finger, pursed her lips as if she were about to cry, which also puckered her highly colored cheeks.

Tipsy and not sure of her balance because the feeling in her big toe was gone, she suddenly sat down, or rather, fell back into the wicker chair, which fortunately was full of cushions and little plush animals, mostly jungle exotics that were the real thing, only stuffed. Her violent fall knocked the chair backwards under her, almost to the leaning vase with the peacock feathers.

Pieter, amazed at everything and everyone he had just seen (this Kilpaison was dark, this was chalk white!), was not quite sure afterwards what happened next. Somehow he found himself seating on a chair close by the old lady--in fact shoulder to shoulder. The grand dame, however, was not a loss for words or wit beneath her impromptu coronet of peacock plumes. She had Pieter come close and then whispered, rapid-fire, confidential information about her granddaughter until Anne cut in with a stinging slap of her glove on her grandmother's wrist. Looking very offended and put out, the grandmother removed her probing fingers from down inside Pieter's shirt and tossed her head girlishly (just like Anne).

"But he's such a nice boy! I can see his possibilities. Yes, indeed, I do! And I was just trying to warn him about the Kilpaison female temperament. You know, dear, our--”

The grandmother hand reached out again to Pieter and this time he colored violently in the face and shrank away.

Anne put her hands on her shapely, little hips and tossed her head just as girlishly as her grandmother. "He'll find that out soon enough. I'd rather you tell him about something you're fond of, say, old Maastricht?"

At the mere mention of the grandmother's hometown, a beatific smile of a Raphaelite angel broke on her withered cheeks, for she was a late, most reluctant immigrant to America. The family had moved from Holland to Jamaica and thence to New Amsterdam when she wouldn't budge.

"Make yourself at home, my dear boy!" she crooned to Pieter. "Oh, do have some of the latest imported chocolates! They're Maxim’s, fresh in from Paris! Sad, but there isn't much to dear, old Paris these days, it gets less and less its old self, but they still know how to make chocolates in the one confectionery that's still operating. I detest our niggardly local Dutch chocolates, don't you? They're hard as rocks and haven't enough sugar and I swear they put in ground corncob or sawdust from some prison mattress factory to stretch the batch--I think it’s called ‘English helper’."

Not noticing there were no fancy, liqueur-chocolates left in the box beside her, imported or domestic, merely a drunk, chocolate-stuffed mouse, the old dowager continued.

"There, now that you’re comfortable and are enjoying your brandy and coffee with cake, I want to tell you about my beautiful, beautiful city. Of course, it isn't today what it was when I was a girl, but Maastricht was the pearl of--"

Pieter listened politely as she gabbled on about her lineage after pointing out a gold-framed pencil drawing of herself in her maidenhood that looked absolutely nothing like her, his eyes dropping until he was staring at an old book titled Lamb’s and Pritchard’s Syllabary stuck under a foreshortened foot of the lady’s chair that had been sawn off for some reason. "Solid, solid burgher," she said. "It's mostly on my late darling husband's side, though on mine, the Van Loons, thanks to events outside my control, West Indian rum traders and Jamaican milkmen of various hues got mixed in somehow--those types are always so wickedly handsome, you know--so that I'm the only one left with a classic, pure, peaches and cream complexion."

She laughed at an old joke she had just remembered. "Oh, there was a whisper or two from my mother before she died that she had noble English blood as well as some of that dear boy, Charles the Great, in her veins, but I think she only wanted us to appreciate her with a more fancy crypt than she knew she would get otherwise from us plain Dutch. By that time, of course, there wasn't much money--the cold-blooded, evil, money-grubbing English side, those upstart Milford Havens, took it all! So they buried her in a pine box like everybody else these days. She might as well been a nursery maid!"

Upbringing: "Oh, strict! puritanical, puritanical! Dutch Reformed! and impossibly, impossibly dull!" Marriage: "Kilpaison, the dear, dear man, was the best husband a woman could ever want; served me the best French chocolates in bed whenever I wasn't feeling my best!" And so on.

He himself could not possibly imagine such a chocolate-dispensing husband, but she was only warming up apparently. She fairly sailed on the subject of her religious training. Her hands moving fluently with the action, she described the setting in old Holland and how a party of her school chums were initiating other chosen few into their secret "Oblate Sisterhood of the Bat-Goddess, Theodora X." Though knowing nothing about Jewish observances, it was to be an approximation of a Jewish bat mitzvah, with a real bat. Their headquarters were the labyrinthine limestone caves of St. Peter outside town. She had got to the place where they sacrificed a hapless summer squash, decapitating it on a stone altar set up before a captured bat, the sainted Theodora (X for rank, as she was the Tenth goddess of that line), when Anne pulled Pieter away to the door.

The old widow flew into an instant sulk, which was half a smile, so it wasn't very convincing as a smile kept interfering with her cross expression. "Must you two go? He is such a darling! Has such possibility, I feel! A little adventure now and then does my heart good! You know how this old lady likes--"

Her hand went out, exactly where it would not be decent to say.

Pieter jumped back away, his face turning red.

“Now you leave his possibilities alone!” the granddaughter protested. “They’re mine--you’ve had yours aplenty in your time, I daresay, and now it’s MY turn!”

Anne threw a shawl over her grandmother’s head when she started to object, and that was that. She and Pieter went down the stairs (Pieter losing his footing and nearly sliding out of control, a lingering effect of the incident in the grandmother’s billiard room), no one showing them to the door except a Great Dane.

Evangeline galloped with the sound of a horse and almost knocked Pieter on his head by jumping up on him. When it happened he had just reached to open the door for Anne and so his crutches were no help. Anne pushed Pieter forward and somehow got the door closed on the wildly affectionate bitch.

How relieved Pieter was to get free of this mad, mad, Jack Dutch Kilpaison household! He had never seen anything like it in all his life--nor did he wish to ever set eyes on it again, if he could help it!

They hurried to take the penny steamer back to Manhattan and, because Anne had a fit until he gave in, another musical show at one of the theaters in gas-lit Heere Street.

On the way he had to question her, just in case. "Did you bring enough money this time?"

Anne tried not to let her irritation show and spoil the occasion as she knew Pieter was probably hoping to do so he could call off the evening out. "Of course! And I have tickets for two."

Theater-going was not his idea of having a good time, of course, but Anne always insisted on going at every opportunity, especially now when they were in between tutors at the Kilpaison "Young Ladies’ Tutors Finishing School." Why he couldn't get her to go to a free lending library of Dutch Reformed religious periodicals and books, or a public art exhibition of government and city schlepen portraits at Van Fricks' was a mystery to him. It was pure malice on her part to say he didn't like fine art, especially when there was no admission charge. He would have rather spent the time with his calculus, of course, but that was too much to expect of Anne. She loved to gad about, though her own house was crammed to over-flow with gaudy, naughty, Jack Dutch books and pictures.

Anne remarked about the theater on the way that it was the only place where young people of New Amsterdam 's better homes could safely hide from the frowning city fathers. The stodgy schlepens, who mostly all lived thick as thieves along Prince's Canal, were always threatening to shut down Heere Street but never said a word about Sin City where they held certain lucrative investments. Fortunately, the hypocrites went to bed early to save lighting their fashionably narrow, high-gabled, seven-storey mansions. She also claimed she had been inside one and seen a private speakeasy going full blast on National Prayer and Fasting Day.

Afterwards, with another penny, it was off to Emilio Hiero Petronio Puciano's oyster house on Ellis Island. Definitely best of the lot, it was run by a Sicilian in an Italian colony, full of family, relatives, friends and buddies, this eatery was a lively place and amazingly cheap. If that wasn’t enough, the music was superb, provided by a Gypsy master violinist who spun sheer magic at the drop of a penny.

Fortunately for Pieter’s mood, the cost of transportation was minimal, or he would have refused to go. Judging from the reception she always got, Anne was a special friend of the family. Everyone fell on her, telling her how much they loved her new clothes while Pieter's face got pink in the cheeks and on his forehead

When she finally got free and they sat down at their table, they were hardly there a minute when a bucket of steamed oysters, newly taken off Nantucket and Cape Cod, plunked down on their table. With fresh breads and heaps of pasta and a bowl of melted butter and another of minty sauce to share between them, they started their meal. Anne had just begin to demolish an oyster while holding it in the shell when she glanced across the table and saw what he was doing. Pieter was throwing down several oysters and then a huge hunk of bread and a mess of pasta as a chaser without bothering to chew.

"Is that the way they taught you to eat where you came from?" she said, eyes snapping. “This is good stuff. You ought to at least taste it!”

Taste the food? Having been born and bred on chaff-filled blue mush and porridge, Pieter didn't know what she was talking about. He continued stuffing and only when she grabbed his hand did he pause.

Though he had stashed away half the meal by that time, she tried to show him something about eating food that would allow him to get a different sensation than just a stuffed belly.

"Why, you eat like some wild animal!" she laughed. “Slow down, it won’t run off your plate before you can eat it!”

After her little demonstration, he tried to chew and handle it the way she did it, but it was no use. He was soon back to his old way, with Anne trying to finish with the little appetite he had not yet spoiled with New Alkmaar manners. When he had finished, long before she had, she looked at him with amazement. "I've never seen anyone eat so much so fast in my life. Where do you put it all?"

Again, Pieter did not know how to respond. It had always been feast or famine in New Alkmaar. Anne changed the subject as soon as she could. Pieter listened most soberly and without the slightest comprehension to Anne's light and sophisticated, big city talk about the latest Heere Street hit.

"Utopia Limited," for that time a lavish musical drama with an opera star singing the lead, was obviously a hit on opening night, but for another reason than just the set and the acting. It was British, and safely staged away from home poked fun at British imperialism--that is, the Clarke family. What could be more welcome to the Dutch audience, Anne commented, than to laugh at former deadly foes while enjoying the spectacle of British actors and actresses pilloring their own country?

After dining, Anne tried to make the best of it this rare occasion with Pieter and enjoyed several glasses of cheap but respectable vintage from a New Gelderland winery while Pieter stuck to plain ice water. It was understood they could talk as long into the evening as they liked. If there was a need for a table or two, Emilio's family simply migrated to the kitchen to make room. No one, once he had ordered and eaten Emilio's fine fare for a modest charge, was ever pressured to pay his ticket and go. That would have been unconscionably mean and commercial.

"Unthinkable! Unspeakable! Unpossible!" Emilio would say if the subject came up.

Customers could wait for the conversion of the Dutch, as far as Emilio was concerned. He always said he ran his oystery for friends and young lovers and nobody else! If he didn't like somebody's looks or the town he came from off-Island (for him that meant not off Ellis but his natal Sicily), he wasn't served. It did not matter a fig how much money he had or how finely dressed. Or even if he brought goons hired to put Emilio in his place. All the restauranteer had to do was whistle. The manhood of the entire Italian community would gladly come running with stiletoes drawn. It was a matter of honor to put any outsider in his place. The eatery was old-fashioned in the extreme but they all made do. An outhouse in back drained like all the other neighboring privies straight into the bay. Since the waters were tidal, a tide chart was tacked to the privy wall. It wasn’t always accurate and accidents occurred.

Flocks of seagulls hanging constantly about the area did not seem to mind what drained and was thrown in the water. Any garbage heaved out the restaurant's back door was immediately grabbed in a free-for-all of beating wings, stabbing beaks, and shrill gulls' screams. Inside, booths were narrow but walled to the low ceilings, so young men courting beaux enjoyed almost complete privacy. From time to time one of Emilio's pretty, sloe-eyed daughters or his ample, moody wife, Placentia Puciano, came by to refill wine and water glasses. But that was all Emilio would permit to intrude upon young people's love-making. As he saw it, not even angels must tread upon love's holy ground.

"Ah, romance is the sauce of life, my children!" Emilio would often say, throwing up pasta-flaked hands. Then he stood beaming with fond memories of his own youthful escapades in country hayricks as Mrs. Puciano looked on with disapproval.

"It's got nothing to do with spaghetti sauce, you old fool!" Mama Puciano always corrected him, but he never seemed to hear. She had a good suspicion he purposely plugged his ears with uncooked pasta batter so he wouldn't have to hear the truth.

She couldn't help noticing other things as well. No two lovers could have been more oddly matched than Anne and her Dutch boy. She with her city ways, he with his countried Dutch manners and aloofness. Why, he ate just like an animal! He couldn't have tasted one bite of all that good food. It was an outrage to civilized sensibilities.

Yes, like oil and water, those two, she thought. Like vinegar and honey... Madame Puciano could see it plainly enough, but no one else seemingly could. But by this time of her life, she was wise enough to say nothing and let people live their own lives (even though she could see they didn’t know how and probably never would).

Anne could see something was troubling Pieter. He was chewing his nails again, so she waited until he was ready to tell her.

"The explosion at the shed," he finally said, after he had put away all he could possibly eat for the days of famine ahead. "I can't help thinking about it, now I'm free of that paper haulin' and sortin’ he had me do." He could well have been thinking about the incident of the starscope, but that was something he wanted to forget.

Anne showed no surprise though she must have been just as shocked as anyone at the sight of the destruction. She shivered, as if in a draught, and pulled her shawl closer. It was news that figured prominently in the papers. Though the authorities had stated their plans to look into the matter thoroughly, she knew from close quarters that nothing had been done to find the culprits. That was New Amsterdam!

She leaned closer across the table, and Pieter wrinkled his nose. It wasn't Anne's perfume, Jamaican Jasmine borrowed from her mother's vanity, but the strong smell of camphor. "Sorry," laughed Anne as she glanced down at her shawl. "Strong, isn't it? I should have given it a good airing first after taking it out of Mama's trunk! You'll have to come again and have dinner with Grandmama soon. She'll probably have another slight stroke from the excitement and lose the other big toe, but when she's feeling better she'll be asking for me to bring you back for a good long talk after she's seen you well fed with her favorite chocolates. Tonight was just an introduction. Father wouldn't ask you a thing we want to know. She's the one who's been giving me counsel about how to look my best. ‘You’ve got real possibilities, my dear, now go get some nice young man’s up!’ she told me. She says that Mama, bless her, won't be needing these things any more and I might as well have them. They fetched her Papa, Grandmama said, so maybe they would work on you too. I guess she was wrong.”

Anne paused in her chatter and looked away for a moment. But when she turned back, her eyes were still merry not sad. Pieter, his more practical Dutch mind on other things than frivolous women's Jack Dutch fashions, said nothing. He was still wondering how to express himself to a temperamental whirlwind named Anne Kilpaison. Ever since the meteor shower, his employer's mood, often tense, seemed to be building as if to a climax. He had even snapped at Pieter, calling him a dunce and other things, which was unlike him.

Gazing at him, Anne's smile faded and was replaced by bold, fierce determination--the side of her that had killed a jaguar finally forced to the fore. She caught his hand on the table. "Well, what do YOU think about the explosion? I hate sitting with an absolute stranger, which you are when you act this way. We might as well talk about it. It will only spoil our time together if you keep thinking and moping about it."

She still had his hand, studying him in the opportunity afforded by the close confines. "I wish I could get you to smile more, so I can see your dimples. You are always SO, SO serious! And your eyes have such a hard expression, like ice. Why, you'll wrinkle up to an old man before your time if you keep on the way you are going."

It took quite a space for Pieter to find his thoughts and respond. It was his feelings that got in the way. He didn’t like cross-examination. Introspection, that was just as strange and confusing to him. When he thought he was being personal, he only became more formal. When he thought he was speaking the plain truth, it was an outright evasion everyone else could spot but which utterly convinced him.

"I--I don't know yet what to think. I just want to do the right thing by Professor Doctor Pikkard. After all the things he had me read and put together for him from the old papers, I wonder if things'll turn out the way he planned. Maybe there's worse than what people can do."

Though not a scientist, Pieter had put at least two things together concerning the balloon shed "accident" and the events in the papers. All the mysterious allusions the professor had made in the balloon the night the stars fell, together with scattered comments made before and after, had finally made an impression. If it had involved people as such, he could never have brought himself to believe it, despite the source.

But forces that went beyond people he could imagine--when normally he could not imagine anything beyond life's basics....

Anne's wonderful, dark, Jamaican eyes darkened even further, culminating in a vampish Clara van Bow pout. Then a smile lit her face. "Oh, you're just too Dutch gloomy. Why be bothered? It's not fate or like walking under a ladder and your whole life is ruined. It's just mean-hearted people who are the problem. I think I know who might be spiteful and wicked enough to have done it! You see, there are plenty people who would like to see him stopped--people in high places. Since my brilliant uncle never felt it worth his while to sue the university for the proper degree to which he was fully entitled, he's always had his detractors there despite the fact it is they who refused to give him his due. Many people who think they are more of an authority in his field are envious of all his scientific discoveries, you see. Perhaps, the worst of them are behind this latest accident. That is the most likely explanation. So now are you going to stop worrying? We know the culprits, and there really isn’t anything Oom will do about them."

Pieter stopped rubbing his troubled head and worry-creased brow and looked deeply into her eyes--truly her chief claim to beauty amidst the unusual, southern dark looks that both attracted and repelled him. "But how can you say that about people like us? I don't believe it. There can't be bad such as that in people. Suppose it has nothing to do with 'people'? What if it is because of a nova?"

His inner self, for a moment, was starkly exposed. That, and the vehemence of his remark, was so startling, his face so contorted again into an old man's mask, Anne was taken aback. She wanted to laugh, seeing his mistake, but he was just too serious and she knew she'd hurt him badly. Obviously, it was a cry of a heart no plain Dutch boy could properly handle, but there was something more which she could not fathom.

Anne's best feature narrowed, and she gave him a strange darting look as her fine, white teeth came up to bite her upper lip. “Pieter, I think you--”

What she may have said in return was not to be as Emilio's youngest daughter arrived with more wine. She took their oyster buckets away and whatever was cracked and uneaten was thrown to her pet sea gulls.

That had given Anne time to control her own thoughts and feelings, and the rest of her remark went forever unsaid. She had just remembered why there was no music--the violinist had that night off. She smiled, brightening up at another thought. "They're all skating on the indoor ice rink in Minuit's Park down by Wall Street. Let's go and rent skates and if we're careful you too can do some slow ice dancing, the kind I like anyway. It's lit up with colored lights like a great big party, there's some wonderful big band music, so it's a really fine place to go."

Pieter, uncomfortable the whole time at Emilio’s, was glad to change the scenery. The free fresh air outdoors also made him feel better. But skating? Even though he had skated before his accident, for the life of him, Pieter couldn't trust his wooden legs on the ice. It wasn't the skates, which were sturdy varnished horn to replace the unreliable, ever-crumbling Dutch iron. Instead, embarrassed to death, he watched Anne leap and whirl around the couples on the ice--a performance that drew the claps and cheers of the other skaters.