C H R O N I C L E

T H I R T Y - O N E

A N N O

S T E L L A E

4 1 3 0

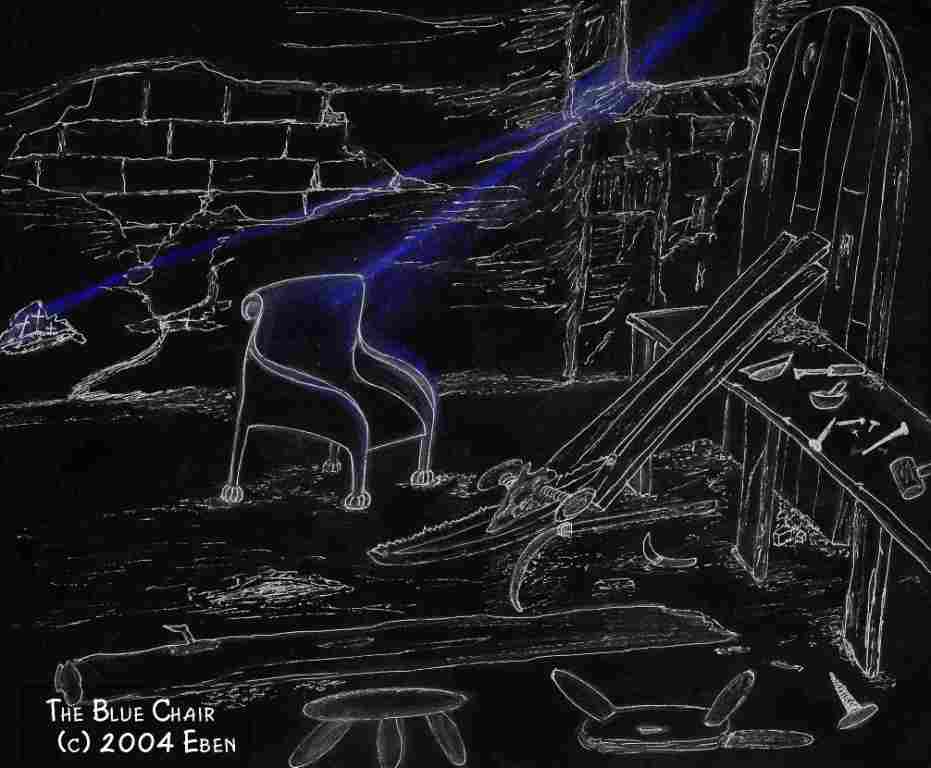

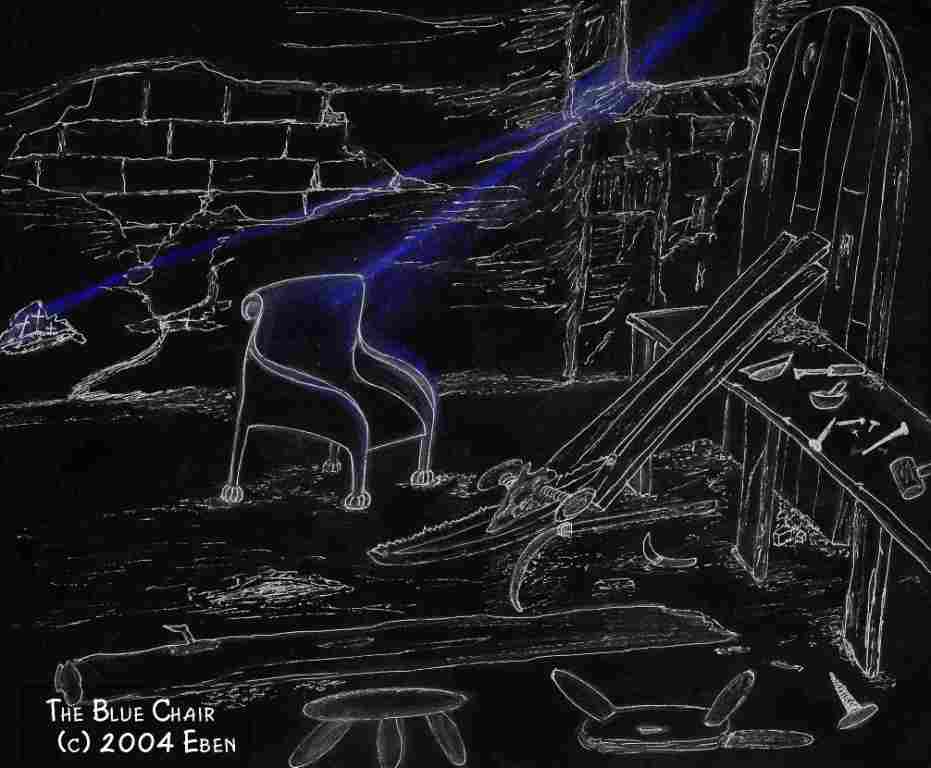

The Blue Chair

Wally’s supposition proved correct. But he had underestimated the difficulty somewhat. It was not a thousand thousand times harder to get the OP to cooperate. On the contrary, it proved impossible. Nothing Wally could think to try from that time provoked the slightest reaction, and so he was forced to wait it out, glove in hand, on the benches until the enemy finally did something observable on Earth. A thousand years and some was, even for a Cray, a long wait. By the time it was over, the new continent was populated and civilized. There was even an empire holding sway over the world.

Old, imperial Rome in all its magnificence and cruelty had risen magically from the dustbin! Roads, palaces, temples, aqueducts, coliseums, hippodromes, public baths, fortresses, seaports, triumphal aches and pillars, the Forum, the Senate, the Imperial Family--truly, OP had done a remarkable job in recreating the gigantic theme-park. Dr. Pikkard, Wally realized, was utterly correct in his prognostications. For all its glory, no one in his right mind would have wanted Tiberius, Caligula, and Nero inflicted again on humanity. But there it was--mighty Rome of the Caesars, ruling all of Atlantis and over subject states in North and South America!

“Heaven help us!” Wally thought as he wandered idly with a tremendous sense of deju vu through the revived empire, trying to figure out how he might put his oar in. “What could OP be up to this time?” And how had OP ever managed to re-create the Jews since there was only a blend of Indians, Mestizos, and Gypsies--with a little French, spanish, and Dutch thrown in--to work with?

Yet, like a thorn in Rome’s side, there were the Children of Israel, complete with the first five books of the Old Testament and their worship of a unique, invisible Covenant-God!

Nazareth, Galilee.

“Why are your eyes always so sad, my husband?” Maryam had a habit of saying, when sometimes she paused in her duties to gaze upon Joseph.

Yosef of course, was not in the habit of replying. So the unanswered question continued to be asked, year after year. It was true the carpenter’s somewhat deep-set, brown eyes were always sad. From boyhood and apprenticeship to his father Yakob, he had the ability to do fine things worthy of the royal line. But who needed them in a rough, wayside town like Nazareth?

Wood dust that normally silted the dooryard and window sills of a carpenter’s shop had almost disappeared when one day a widow--a well-to-do relative of Maryam’s--came by after an absence of a year or two.

She noticed, when she reached to touch it, that the mezuzah was so neglected that the tiny scroll of Deuteronomy 6:4 had slipped partly out a crack. They needed a new one, but, obviously so poor a household need not expect much visitation, so the expense was needless. So she was thinking as she went indoors.

“Well, how is business?” Noahdiah remarked socially after the family gathered in greeting. With her keen eye for business or no business, she knew quite well how things stood in this impoverished branch of the family. Now this remarkable woman had outsmarted the town elders--the usual grasping sorts--and even increased her late husband’s holdings by shrewd investments in Egyptian wheat for the Roman market. “Your income up, or is it still flat?”

Disliking busybodies and talkative women, Yosef did not look her way. He kept silence as he rummaged in a bag of tools, as if looking for something he needed.

“Well, son of Yakob,” she said. “It’s obvious there’s nothing wrong with your fountain, but as a provider for my dear niece what do you, a grown man, have to say for yourself? You’ve had years to make a go of it here, and have you? Well, answer me, or has a creditor got your tongue?”

Yosef winced but kept rummaging, eyes shrunken in their deep-set sockets.

Maryam suffered the indignity of her auntie’s outspoken tongue with grace and quickly tried to turn the conversation.

“I hear dear Cousin Elizabeth is in fine health, and her son Yohanan too, and he’s gone to live--”

“Yes, like an old-time prophet, in the Judaean wilderness!” snapped Noahdiah. “You need not tell me his follies! I hear them every day at the market. My, how bad news gets around these days--particularly when it has to do with my idiotic, ne’er-do-well relatives!” She gave Yosef a sidelong glance full of meaning.

So the talk went about Elizabeth’s unconventional, bachelor-son whom Noahdiah called a good-for-nothing while Maryam’s first-born, Yeshua, listened intently.

Only for a moment did the older woman pause for breath, order a chair from Yosef like throwing a dog a bone, then return to Elizabeth’s son who, she said, was entertaining delusions he was the Messiah’s forerunner!

Finally, the talk about Elizabeth’s strange-acting, wayward Yohanan exhausted, the esteemed relative departed, leaving the family in considerable stir; but this time it was not a bad scene she had left two years previously, for Yosef was busy, even humming a hymn of praise. He was in such fine humor, in fact, he ignored Maryam’s call to dinner as he worked on the new order.

Since the widow could well afford it, he was determined to fashion her the finest chair Nazareth had ever seen. And the moment she had mentioned the poky, misshapen thing she was after, he had seen something else in his mind’s eye--a chair he glimpsed once in a fine shop in Sepphoris. Slung low in the arms and back, it was nevertheless noble style, with elegant, slender legs terminating in lion claws. That this particular chair was an alien, curial Roman design did not occur to him. It was a thing of rare and simple beauty, something he had always dreamed of making for a prince or king of Israel.

Scrutinizing the ordinary pine and oak he had on hand, he realized at once he would have to secure better material for the “Messiah’s Chair.” That meant a trip south to a forest where he was certain he would find the right tree, having passed that way many times, once for Yeshua’s birth in Bethlehem, and afterwards at Passovers.

Since his first-born James was so careless and awkward he obviously was not going to make a carpenter, Yosef called for Maryam’s. It was most inconvenient, Maryam observed. Yeshua was impelled to leave his herding of a neighbor’s sheep, to run along with Yosef to the Judaean wilderness to be mauled by lions and wolves when the income Yeshua’s work brought was so badly needed, so badly needed.

She nevertheless packed them up some bread and cheese and watched them set out carrying tools and extra cloaks for sleeping on bare ground. With heaviness and fear piercing her mother’s heart, she stood for a moment, letting her loom wait precious moments as she mentally followed their footsteps down the road from the house toward Judaea via the Jordan Valley--a particularly dangerous route.

An anxious week passed before they returned by the shorter way, through half-heathen Samaria, bent over like donkeys carrying the sawn boards of fine myrtlewood.

With no thought for anything else, the carpenter then sailed forth into his new project while James and the oldest boys worked another new order, some farmer’s crude plow. But the chair never seemed to take a finished form, as much as Yosef lavished his labors on it. He was never satisfied with what he had accomplished, but was forever starting over, discarding week after week of previous efforts. In time it seemed to Maryam that her husband had quite lost his mind. He devoted all his energies and time to the chair while he let paying work--plows, always more plows!--go.

Meanwhile, the chair’s prospective owner continued to play the busy townswoman, wheat speculator, and community marriage broker. Despite being so occupied, from time to time she sent a hired girl to make inquiries, but somehow Noahdiah never found opportunity to come by for a look herself.

Then, not surprisingly, she completely forgot about the ordered chair in the press of important business and money-making.

Yosef made several trips to Sepphoris simply to gaze upon the heavenly blue chair he had seen in the shop of the carpet dealer. He stood gazing at it so long the proprietor, a cultured half-Jew from Alexandria, thought him daft and grew impatient. When Joseph came again, the chair was not in sight.

“Where is it?” Yosef demanded with a countrified brusqueness of speech, desperation welling in his eyes. “What have you done with it, you rascal?”

The tradesman struggled to loosen Yosef’s powerful grip on his stylish, Roman-style toga. “What

are you talking about? Have you come to look at carpets or what?”

Yosef turned away in sadness. Without the model, he would have to finish his chair by memory.

The shopkeeper looked at him with mingled pity and disgust, for he had seen enough of these smelly, dirty, broken-down brethren from the half-civilized countryside. Without a shekel to their names, they liked to come and gape and finger his lovely carpets. It was a relief to him when the scruffy, bearded Nazarene finally left the shop. As soon as he thought it safe he brought out the Roman-style senatorial chair he reserved for wealthy Roman and Greek patrons. He had had it repainted a crimson-lake hue--the latest fashion in furniture. Besides, a change in color might throw the bothersome yokel from Nazareth off and he’d go darken somebody else’s door.

Noahdiah stopped by Yosef’s house one day. Almost at the doorstep as she reached up to touch the mezuzah, she happened to remember the old order. Going in, after calling loudly to see it, she gasped when Yosef brought out the finished product of all his skill and misery. Instantly, a scowl disfigured Noahdiah’s face ear to ear. Her expression required no words of explanation, but she was not a woman of few words like her niece.

“What is this?” she demanded, throwing up stubby, ruby-jeweled hands. “I expressly asked for a decent, ordinary, straight-backed stool, without this blasphemous, foreign style. In other words, a good Jewish chair!”

The carpenter turned ghastly pale, but he could not be dashed at this point, for he knew his craft.

“Woman, this is the best I’ve ever done!” he cried. “Look! You have eyes! Don’t you see it’s chair fit for a king?”

The good woman, who prided herself on her keen eye, would have none of it. Without waiting for customary hugs from the children, bows, and a parting kiss from Maryam, Noahdiah took herself off in a great huff. Ignoring the mezuzah, she muttered, as a parting Parthian shot, something about frivolity and want being bedfellows as she bustled off down the road to town. She was, indeed, in such a hurry she forgot the reason for her call. Poor Elizabeth’s Yohanan had gone berserk from starvation, sleeping on bare rocks, and his womanless life. Locusts in his mouth and half-naked in a camel-hair rug, he was preaching on the banks of the Jordan, calling everyone, even temple priests from Holy Jerusalem, to repentance! Could anything be more absurd? It was a good tale, just oozing with juice, and Maryam would have swallowed it whole and cried bitterly.

When she remembered, she was too far from the house to want to make a second climb. Disgusted at herself for missing such an opportunity, she wasn’t watching approaching traffic until it was almost too late. She stepped off the road into the ditch. It wasn’t a moment too soon. A red-painted chariot hit the crossroads, hooves and wheels flinging up dangerous stones and a lot of choking dust as the foreign devil passed Noahdiah with hundreds of troops on horseback. When the tremendous commotion died down, the old woman knew just what a good Jewish woman should do.

“Abomination of abominations!” she spat into the whirling dust in the wake of Pontius Pilatus the Governor-elect, as he sped on his way from the palace in Caesarea to Jerusalem to take charge of the Roman fortress, the Antonia. Now it was good Jewish custom to spit whenever a Roman or, worse, a Samaritan passed, since such were known idolaters and carried images of heathen gods in defiance of Moses’s commandments. Her patriotic duty done, Israel’s honor vindicated for the moment, she glanced sharply right and left, then hitched up her skirt, revealing a misshapen, thick leg garbed in a sagging, much-patched undergarment. Quickly, lest her virtue be exposed to the gaze of a dog or Roman, she plucked at her lower limbs. Somehow tiny burrs worked up her legs, as far as --well, it sometimes happened she actually sat on one, and then all Nazareth heard the shriek of Abagtha’s daughter.

Minutes after Noahdiah was gone and the carpenter’s household settled down into despair and poverty, a big blue butterfly happened by, paused to look in at the open door. He saw there was nothing it could possibly do and passed on, following the chariot and troops on the road.

Maryam did not see the Roman’s flame-red chariot. Yosef’s little house was turned away from the road. What few windows let in air and light were too high up for viewing comings and goings on the public highway.

James and his younger brother, out herding a neighbor’s sheep, saw the chariot. But they were not surprised, having seen Romans and Herodian royalty pass that way before. Nazareth was a place procurators and tetrarchs had to pass, from east to west, and south to north, though none would think to stop in such a dirty place.

C H R O N I C L E

T H I R T Y - T W O

A N N O

S T E L L A E

4 1 3 3

The Sixth Hour

“How do you like it?” Pilatus said to his wife, as they stood together in his consular chariot somewhere in the Judaean wilderness. “Is it not a worthy rival to that sniveling, little Jew’s in Caesarea?”

Despite protests, he had dragged her into the desolate inferno south of Jerusalem, just so she might stare at his latest architectural triumph, an ordinary, third-rate, provincial aqueduct!

“My lord, why do you always call the late Herod the Great a Jew? You should know very well he was Idumaean from the south, perhaps half Jew at best. Surely you can understand why the chief priests bitterly resent your naming him one of their people.”

Pilatus laughed at her silly woman’s talk. What splitting of hairs anyway! Idumaeans? Jews? Samaritans! You couldn’t tell one from the other, looking at them, and he saw them every day, hour on hour! Long, dark, scowling faces and big noses that swept the ground, baggy robes smelling of goats and sheep, untrimmed beards and a religion that defied all rhyme and reason--ugh! There wasn’t any difference worth mentioning!

She would have said more, but he interrupted to point out first one feature and another of the project, explaining where the stones were cut and how they had been laid by his engineers and slaves, until Procula was beside herself for boredom and discomfort because of the burning heat.

It was midday, the sixth hour when only dogs, Roman sentries, and now a Governor and his wife ventured out amidst the deadly light. She reflected how Pilatus thought nothing of taking her on a trip during the worst part of the day, exposing her matchless complexion to the pitiless sky, not to mention Judaea’s famous, biting gadflies.

“May we go now?” Procula wanted to know, after enduring all she could of Pilatus’s play by play reconstruction of the aqueduct.

But he ignored her and drove in closer to the arches. They spanned a deep ravine, so he was foolishly discounting the danger when he drove off the caravan road and into rocky terrain.

Procula was alarmed. “We’ll die out here in an hour if we can’t get back, Pilatus!”

He continued driving on full-speed, and the wheels scraped rock and almost threw Procula out when they hit a crevice. Whipping the horses, the wheels pulled out, and finally the chariot stood on a massive table of naked, scorching-hot rock, the perfect platform to view Pilatus’s creation.

“It’s a sublime specimen of our Roman engineering, is it not?” the builder crowed, his voice booming over the scene. “Only there is much more to come than meets the eye, beloved!”

“What do you mean by that, ‘much more than meets the eye’?” she shot back. “What I see anybody can see in a hundred such wretched localities as this!”

The procurator looked back at her, his lips curled, as if he savored the moment. His chuckle kept erupting, and he could scarcely keep it in check out of a sense of awe for his own achievement. “Well,” he drawled, “I wouldn’t want to spoil the big surprise when it comes, but I going to upstage the pretty boys in Capri. I’m not just planning just any aqueduct--you see, this is going to take not only water but a third level, strong enough carry the new steam wagon caravan! His favorites at court may think they can impress the Emperor there in Rome, but he will soon know that I, Pontius Pilatus, am ahead of them--far ahead!”

Mystified, Procula stared at him for a moment. “What--what are you saying?”

Dragging it out to the point of nearly making her scream, the procurator lifted his nose and chin high and gazed imperiously this way and that, studying the fine view as it were, when he abruptly ceased playing with her. “I mean that I know all about the new and mighty engine and roadway-system Rome is going to build and send all over the world--the steam caravan that pulls wagons full of troops and supplies, dozens of them, all at high speed! Now, if you don’t believe me, just look there! What do you see?”

She followed his stubby, jabbing fingers and saw piles of timbers, some metal, the others wood.

“Rome’s mechanical wagon caravan will run on a special roadway made of those, and--”

Her mind whirling, Procula could not take it in. Steam caravan? Special roadways of wood and metal? Able to move the legions rapidly all over the empire? She knew now that he had gone mad. Terrified and furious, Procula could not find words. She blamed herself for giving in to his mad idea of the aqueduct, thinking it would involve only an hour or so of discomfort in the chariot.

Now she knew why he had driven so far out. The arches nearest Jerusalem, where the channeled water decanted into Pilatus’s modern system of lead pipes that served the Fortress Antonia, were not nearly so massive and high as here in the country. Here he thought to impress her with the magnitude of his construction. That was the reason for him dragging her into the countryside.

While she made up her mind what nonsense he was spouting, Pilatus continued to expound to her the immense difficulties of the site he and his engineers had triumphantly overcome so that the “steam caravan” could proceed safely to Jerusalem. She didn’t believe a word about it and tried to counter the droning statistics and bombast by thinking of where she longed to be--her Etrurian-syle villa near Rome, rather than the barbaric deserts of Judaea. At that moment even the too-formal, too-Roman governor’s palace in Caesarea seemed appealing. There was even a small synagogue somewhere on the outskirts she might take a chance on visiting...

“Pilatus, the horses!” she had to remind him. “They’re fainting! And your wife is fainting! We must go back now, or we may never get back. How they would talk about that in Rome and Jerusalem! And that would jeopardize my--I mean, your plans to become full Governor. You don’t want to remain a legate’s minion all your life, do you? Even if you’ve been accepted as a Friend of Caesar, the club doesn’t like newcomers, particularly when they’re not exactly Roman in blood like you--”

Fortunately for her, Pilatus wasn’t listening to all she said. He laughed, both armpits streaming.

“You would never make a Roman infantryman!” boasted this descendant of an old, somewhat decayed Samnite family that was known for producing both tough fighters and village idiots.

He leaped briskly from the chariot, which was radiating heat like a crucible for refining silver.

Ignoring his despairing wife, who now felt dazed and tried to fend off the radiation by covering her face with a fine, silk scarf, Pilatus drew his sword and began to creep toward the nearest arches.

Amazed at his action, Procula got down from the chariot. She was glad to move from the furnace of the chariot, but felt the rock scorch the undersides of her gilt slippers. She limped across the rock to see where Pilatus had gone. In a minute the stealthy form of her husband reappeared by the aqueduct down below. She saw now what he was after.

A little band of five or six harts were gathered in the shade of the arches. They were so intent on their own needs they did not notice the approaching procurator.

Shading her eyes, Procula tried to determine what the golden-brown creatures wanted as they leaped again and again, as if straining to reach something. Their movements were almost frenzied as they leaped, pawing the air with dainty hooves. Procula’s eyes widened as she saw her husband suddenly dart forward into the midst of the harts. She was back in the chariot when he returned, his eyes glinting with excitement like those of a beast of prey.

He turned the chariot round on the big rock, and somehow the half-dead horses found strength to drag them back to the road. By this time Procula felt as if she might not live to see Jerusalem and her beloved Etrurian villa again, and so said nothing. Her head felt afire and her limbs melted. But Pilatus sang some army camp song. He was flourishing in his element. “I could have gotten one or maybe two with a decent javelin!” he finally acknowledged. “This fancy sword is for slaughtering men, not hunting.”

One image haunted Procula’s mind even as the walls of Jerusalem loomed on the horizon--those

graceful, horned harts leaping so strangely and frantically into the air. “Why were they all jumping like that?” she asked.

Pilatus laughed, without looking at her as he kept whipping the horses on toward the Fortress Antonia. “My dear, a woman knows nothing. In desert country like this harts hanker for sweet, flowing streams such as we captured and channeled strictly for the use of my aqueduct. Since they scent the water, water they’ve been accustomed to drink in the past, the stupid things were still trying to get a drink! In truth, they will do that until they drop dead of exhaustion and thirst rather than go find some other source of water. That’s how dumb these wild creatures are!”

Since her husband seemed to be amused at the thought of the animals’ vain attempts to reach piped water, Procula inquired no more. She was only too glad to reach the fortress, shade, and more water than she and the ibex could use in a lifetime. Getting down from the chariot, she nearly collapsed along with the horses.

As maids rushed out to help their mistress, guards drew swords. They dispatched the gurgling horses on the spot as Pilatus shouted needless orders. In all the activity no one noticed the lone blue butterfly flitting high up by an open window in the tower.

C H R O N I C L E

T H I R T Y - T H R E E

A N N O

4 1 4 6

The Dreaded Day

As for the rejected chair, it had settled deep in dust and shavings when circumstances combined at last to force Maryam to make a decision.

Maryam had guessed Yosef’s heart was broken the moment her aunt looked with outrage on the chair. Yet she knew that it in itself was too trivial to snap the thread of life. No, she did not know the true reason for his falling over dead one morning, years before his expected time.

Before that, she observed Yosef day after day while he was slowly turning gaunt, but never did she divine what was unraveling his life, little by little. Not being able to help him, or turn the running, dark thread of things to the right, caused great anguish. Yet Yosef’s death, when it came, changed their lives very little, she found.

Her hard work supporting a large family remained the same, and life was still a perplexing tangle. What changed was Yeshua. From attending Yosef’s whims and helping perfect the useless chair, to leaving home and visiting his cousin Yohanan camping in the wilderness, he had done nothing willfully against her wishes, nevertheless he had worried her. But when he turned to staying away from home for weeks at a time in some lonely, wilderness cave, her first-born’s behavior had changed from merely strange and worrisome to truly alarming.

As she worked at her loom she had time to think the change over. So many years had passed since Yeshua’s solemn dedication in the grand Temple of Herod, when an old man of holy manner, Simeon, and an aged seeress, the widowed Anna of the tribe of Asher, blessed her son and said wonderful but incomprehensible things. That was all very well, though the two who gave somewhat lengthy blessings did not know they were detaining the family from a long journey home and taking valuable time away from the pressing duties that awaited them back at their door.

Yeshua's circumcision, of course, had been performed the eighth day of his life. She wouldn't forget how he had slept badly that night, and she had watched him the whole night toss and turn, his eyelids and one cheek swelled. That wasn't supposed to happen, but she noticed how dirty the priest was who handled her baby. Could it have been his uncleanliness? Her relatives laughed at the thought, but she couldn't put it out of her mind that somehow his dirty hands and dirty knife caused Yeshua's discomfort.

The same family experts on the covenant seal advised her that she should have given a sacrifice of two lambs first, and spared herself and the baby a restless night. Parents who did that always incurred God's favor, she was kindly informed. But where was she to get the money for the lambs? Joseph was hard put to support them, being new in Nazareth and few people venturing to employ him on carpentry or masonry projects.

Taking Yeshua to the Temple again when he was twelve was a big mistake. He had spoken and done strange, adult things that gave her real, bitter pain and alarm. Yet she had mastered her heart’s cries in time. She herself had prompted him to perform a public sign at an important wedding. He had done so, confirming her belief that he was, indeed, God’s Anointed.

Had she done wrong in encouraging him at the wedding? she wondered over and over. It seemed right at the time. After all, he was a grown man and needed to begin reigning as God’s Anointed. How could she support the family without his carpenteering? But as the acknowledged Messiah of Israel, he would surely gain an income from the Temple and be able to support her in her old age as the law decreed.

A hand went up from her weaving and momentarily drew forward a long strand of her hair. She stared at it. It was now undeniably gray. She hardly knew herself anymore, for her hair had turned well before its time.

But time had passed too swiftly for others too. Except herself, everyone at Yeshua’s dedication was either deceased or too old to remember it. And she and Yosef had told no one about angels and prophetic utterances, just as they had kept all details of his conception secret. No one would have understood it. There had been some naughty talk, chiefly in her aunt’s circle concerning Yeshua’s “sudden coming to birth” in Bethlehem only six months after Yosef took her officially to wife.

“How do YOU explain it, son of Yakob?” her aunt had even challenged Yosef face to face on a visit to Bethlehem. As for the strange, red indentations on the baby’s wrists and feet, no one could explain them either. Then the couple had gone away and lived in a foreign country for a while and years passed and no one said anything openly against her anymore, as far as she knew.

And Yeshua had done so well at synagogue school before Yosef put him to work full-time, tending neighbors’ sheep and goats. The rabbi even recommended sending him to study in Jerusalem, to train as a scribe or Pharisee. Of course, they could not afford to let him go, neither could they support him away at school, so despite the rabbi’s advice they let the matter quietly expire.

Proficient at carpentry, Yeshua seemed to have found his niche in life at an early age. Yosef was pleased with the boy’s attitude, demonstrated skill, and cheerful obedience. That training had stood him in good stead when the family’s head was gone. He took up where Yosef left off, with the difference that his efforts were blessed from the start. Indeed, the last six months had brought more orders than he could handle, so all hands were required to help, except for the ones on the old loom, of course. Income increased so much Maryam was able to put money by for the first time.

Maryam had almost forgotten the old troubles and misgivings when, several months after the wedding at Cana, Yeshua completed his work on the new door for the synagogue. He had just finished the intricate carving of clustered grapes and shocks of ripe wheat. They were so true to life his youngest sisters touched them with wondering fingers.

It was then he went over and watched his mother for some time as she worked facing toward the loom and the cracked, adobe wall. “You do very beautiful work,” he murmured, when she glanced back inquiringly.

“How can you tell, my son?” she laughed. Full of fine days, her heart had lifted to a former girlish gaiety, so much she was even humming as she span.

Yeshua did not reply at once, for he, unlike Joseph’s sons, had Yosef’s quiet ways.

So Maryam continued. “The pattern is not visible on this side, so how can you say it is nice to look at?”

It was true, the side on which she worked was a total blank--and sheer black as goat hair. As she unwittingly wove Herod Antipas’s bedchamber tapestry from behind, the pattern appeared only to her inner eye. Yet she always did flawless work, revealed only when the finished piece came down from her mother’s old loom, though she could not have explained how did it.

“What is the pattern, if you cannot see it?” he asked.

Maryam was amused and almost laughed. “Why, it’s a rose on a long, leafless stem, with a twisted briar on each side.”

“How strange, a rose between two briars?”

“Yes, but I know somehow it will turn out lovely in the end. A picture came to my mind at the same time of a tree in full foliage, with two woodsmen on both sides chopping it down, but I didn't like that and chose the rose pattern instead.”

Her first-born, like Joseph, did not reply for a long moment.

“Yes, it will,” he agreed, as if he could see the finished tapestry already.

Yeshua’s next remark, when it came, stopped her shuttle cold. “Woman, I am going away.”

THIS, then, was the dreaded day! Maryam knew it in an instant. Her shoulders flinched. She turned round on her stool, pain compressing her eyes. “You are a man, my son. Will you be seeking a good wife now and then move to the Temple now that you are beginning your reign?”

It was a reasonable question, though she dared not ask the question that was really on her mind.

She had expected Jesus to decide on a future mate when given the opportunity at Cana. But Nazareth had plenty of nice girls too--many connected to their own line of David. Only her auntie--

“I am going to see Yohanan. He’s baptizing in the Jordan.”

Maryam was appalled. This was not God’s divine plan for her first-born, she knew! Gleaming, silver thread suddenly clenched and twisted in her intelligent, long-tapered fingers. But her first-born did not wait to discuss the matter. He went to embrace his brothers and tearful sisters. Then he pulled on his cloak, shouldered the new door for the synagogue, and went out of Mary’s house.

Afterwards, in deepening dusk, Maryam made no move to light a lamp and sat before her loom, wondering what to do. Things were going so well! Why did Jesus have to leave now? How long would he be gone? Maybe it wasn’t the dreaded day after all. But if it was, would he become another ragged version of his peculiar, savage-living cousin, opposing and speaking evil of the Temple authorities? What would she do then? How people would talk! After all, she knew him as the Lord’s Anointed. He was not a wild man, not her beloved, gentle and mild Yeshua who always did such fine, caring work! The high priests would surely accept him as Messiah, if he would only seek an audience with them and speak respectfully to them of his calling and the proofs and signs God had already given to confirm it. But Yohanan! He would only lead him astray with his rough ways of living and speaking against important people!

“No, don’t be like Yohanan!” she prayed over and over, her heart turning over in agony and fright. “Oh, God, not like poor, dear Yohanan! Not like him!”

Copyright (c) 2004, Butterfly Productions, All Rights Reserved