Meanwhile, like a great, irresistable river that never ceased pushing this way and that, as the Atlantean threat ebbed, events boded ill for the future prospects of Khian’s throne, involving Wally to even greater degree.

She seemed to catch a new vigor as she breathed in the outer air after her long seclusion. Ramoseh would often come and tell her of new projects or how the work was proceeding. Zenobia would make comments as though everything he said was of interest to her. Assah wondered, however, if she were not listening and answering to Ramoseh because she saw so much of Joseph and his God in him. It came as a confirmation to Assah when Zenobia called Ramoseh, sending him on an errand for her now that the busy seedtime was over. Zenobia knew Ramoseh could be called from the fields, leaving a man in his place. There was only clearing of irrigation canals and weeding since all the fields had been sown and traditional Seed Festivals spread throughout Mizraim.

Ramoseh departed from the house and struggled through tipsy, celebrating crowds to the prison of Potiphar. He returned late in the day with news of Joseph for Zenobia. "The Invisible God continues to prosper my master in prison!" he exclaimed, unaware of his slighting of Lord Potiphar. “The warden has put all things under his charge.”

She in turn took the news to Potiphar, who was amazed to see her speak sanely and evenly, without tears or hysterics, as she related how Joseph had reorganized the prison and made it highly productive.

Potiphar was not very interested in hearing the details (women, he thought, were too much taken with domestic facts), but he listened to it all to please her. Zenobia herself was happy with the news Ramoseh had brought. She left Potiphar and went back to her apartments to tell Assah and mull over the story for many hours. To Zenobia it was another sign of the greatness and majesty and steadfast love of Joseph's Most High God, while the pompous gods of Mizraim were found sterile and lacking as cross-mated geese.

She thought how the priests and wizards would not have done it Joseph's way at all. To find out what steps they should take in any matter, they all dropped red or black ink in divining cups or traced Destiny in messy entrails and livers of animals. The signs were often very conflicting if more than one wizard (or ink spot) was consulted. How much better was Joseph's way! she thought. His God could communicate directly when understanding or direction was needed.

Curious to know more, she waited and then sent Ramoseh out again. When her dove returned with more news, Potiphar waited for her to come to him, no longer merely indulgent but interested. There had been so much bad news of late about the country, it did him good to hear Joseph’s accomplishments.

Khian had reason to be upset, he knew. The traditional royal seat of the city of Machitha, with an immense palace of plastered and painted brick that gave the city its name, "The White Wall," had been lost to the Ibbathans. Machitha was the first capital of the United Kingdoms; there the double throne was first set by Narmer, after the Lotus King of the Upper Kingdom had fought and decapitated the Papyrus King of the Lower. Wearing the two crowns in one, the white crown of the south and the red of the north, Narmer built Machitha's per-aa (or Great House of Machitha). To Ibbathans and Hyksos alike, Machitha and all its associations with sovereign power was Mizraim; whoever held it held the heart and soul of the realm. Losing Machitha, Khian forfeited the last shred of his own throne's legitimacy. Seed Festival or not, the enemy was now at the gates of the Delta, rising up against Khian's last strongholds like the waters of Ioteru on the stepped stele that stood at the delta to measure yearly inundations.

Heads of generals, not to mention those of chief officials--the Grand Taty, Masgeh and Opeh--had to roll in Khian's court to account for the terrible loss. With the distinct possibility that Nathasta would be next to join Ibbatha against him, a cornered Khian had sunk into a dangerous and desperate frame of mind. Potiphar knew that only the relative success of his latest trip to Nubian Kush had saved his own life. Now the Per-aa could not let his ire fall on him, lest he have no commander of any stature to call up in the final thrust of the Ibbathans on his capital--an eventuality everyone knew was imminent.

Soon after Machitha's fall, all of Avaris was thrown in an uproar over yet a further sign of judgment that eclipsed Khian's prospects. The House of Eternity he had worked to complete on the western side of the River, built of the finest red granite, had proven unstable. Khian, to save time and funds, had struck out Petepheres his chief architect's inner walls that would have directed the stupendous stress and weight inward. The structure was three-quarters finished when thousands of highly-skilled, paid laborers began to throw away their tools and run in shrieking terror down the earthen ramps that lifted stones to the top.

The overseers could not get them to return, for they had heard the chrysalis "speaking," that is, groaning with the terrible sighs that pressaged doom. Some even claimed they heard the distinct word, “Woe!” repeated over and over.

Whatever they were saying or not saying, the very stones they freshly laid were moving perceptibly outwards! So they fled the monument to Khian's posthumous glory and would not return to the work, no matter how much beer and bread they were offered and ointments for their bruises and tired limbs.

Then, in the night after the work was discontinued on the chrysalis an extremely rare but violent rain fell on the work. Soon all Avaris heard a rumbling, as of the sea bursting full on the land in a vast wave. In a few moments years of labor by a great army of workmen and slaves were no more. The House of Eternity exploded in every direction, hurling 20-ton blocks like pebbles as far as mid-channel of the River. Khian's grand funerary chapel, chrysali of various officials and the chief architect, and part of the roofed causeway leading to the embalming chapel at the riverside were also covered in rubble from the explosion. In the morning the Per-aa's men found broken and tumbled stone. The dissolute, declining Hyksos king would never know immortal life. The expense of building another House of Eternity was beyond his means, especially since he had lost most of his country and his chief treasure-city, Machitha, to his enemies.

People were even saying aloud that the foreign Per-aa had offended the gods. After all, he steadfastly refused to wear the sacred bull's tail attached to his belt in back. It was also common knowledge his scepter was capped not by Nebel the falcon-god but a Hyksos demon combining a dog's head to a donkey's body (certainly the two most despised and loathed creatures in Mizraim).

Rumors and twisted bits of the truth darted everywhere about the falling capital. The whole effect was to belittle Per-aa Khian, reduce him to a mere man or less than an infallible god. When that was accomplished there was much unrest stirring that would eventually tear down the locked and guarded gates of the palace itself.

Knowing these developments and their outcome, Potiphar turned to his wife (who had been secluded from the world and its troubles), expecting to hear something gloomy.

Zenobia's face was radiant. "Joseph wants you to know he has forgiven and is at peace concerning this house!” she informed him. Zenobia seemed childishly pleased, so Potiphar, for whom forgiveness and reconciliation carried precious little weight, did not say anything.

Thinking to humor her, he let her go on. “My lord, I heard he has a gift of understanding God has given him concerning dreams. I had a dream not long ago. Ramoseh took it to Joseph for interpretation. I dreamed of a golden sickle cast into the midst of the sea, where it reaped tall mountains of their crowns and scattered them like dirt across the earth. And in the white sands of the shore rolled up a great, stone head of a god's image. And as I watched it, the head rolled inland, striking against each city as it passed and casting down every high place and god, smashing them in pieces, so that none stood against it. Finally, the head rolled up against a mountain that broke it in pieces."

"And what did Joseph say?" Potiphar replied as mildly as possibly to Zenobia's long-winded whimsy.

Zenobia seemed n ot to hear him. Her gaze seemed averted by something she must have seen in the telling. "I have seen that head before. I just cannot remember where. I know I have seen it!"

Before Potiphar could ask her again about Joseph, she went out, shaking her whitened head.

He never did get to ask Joseph's interpretation. The dream seemed erased from her memory, and with it the meaning. Zenobia had other things on her mind. She wanted to be taken not to her pleasure boat but Joseph's seagoing ship.

Potiphar was somewhat alarmed, but after instructing Ramoseh to pay close attention to his mistress let her go. After Zenobia's numb and mindless lethargy, her old energy returned with a vigor and purpose that startled Potiphar into wondering what she had in mind for the Ioteru, as Zenobia called the ship.

The collapse of Hyksos rule was most pressing, even though he purposely stood by in the shadows as much as possible. The ship might prove their only means of escape, when the Ibbathans stormed the city and slaughtered everyone connected with the foreign court. It was only a matter of weeks or days before they rushed in to secure the double crown and the other insignia of per-aa-hood stolen from Machitha's throneroom by bygone Hyksos generals.

Worshipped as gods themselves, the crowns of the two lands were mounted with the sacred uraeus-cobra that supposedly spat poison at whomever happened to touch the Per-aa's sacred person. As long as Khian had it, this double crown, so ridiculous in size and heavy on a ruler's pate, was the only thing that prevented an Ibbathan taking full control of Mizraim’s allegiance. Of course, Khian would have to be killed if the double crown was to be fully restored to a Mizraimite. Though he hated wearing the contraption and threw it aside at the first opportunity, there was no doubt Khian would rouse himself from his dissipations and fight to the death to keep it.

At this fateful time a complication was injected into the fray by custom and tradition. Every twenty years of a Per-aa's reign a national jubilee was proclaimed and the Per-aa was obliged to run the 17-mile circumferance of Machitha's sacred white walls. It was the traditional test of a ruler’s physical powers and stamina. If he dropped dead--the gods forbid!--he was obviously unfit to reign over the land. Everyone knew that Per-aa Khian had been in power twenty years. But who was the legitimate ruler of Mizraim? The Mizraimite claimant in Ibbatha who had "reigned" but a few years or the “foreign chieftain” interloper in Avaris?

All loyal to the Mizraim of old thought the claimant was entitled to run the race, but those who knew his spindly legs and flat feet despaired of his ever proving his potency to his subjects in this way. Even if the Ibbathan pretender could muster enough strength to run in Khian's stead, he was still not wholly legitimate. No royal prince could seize the throne on the basis of Mizraimite blood and lineage alone. Everyone knew the throne descended not through the per-aa to a son or a favorite but through the per-aa's daughter to her husband at the precise moment she imparted the Royal Secret of Succession.

And where was there a daughter of the last, true, Mizraimite-blooded Per-aa? Royalty and its right to rule had become a most complex and tangled affair in the present Mizraim. Legitimacy had seemingly been lost in the turmoil of the Hyksos invasion. With such annoying considerations on his mind, Potiphar had much to think about as he sat in his rooms pondering the course he might have to take if the Ibbathans ever found a way out of their messy predicament.

He had Zenobia and his servants to consider. Though sequestered for life in a dungeon, Joseph was quite safe, indeed safer than the general populace of Avaris. Should the Ibbathans attack, the delta was, except for the area around Hyksos fortresses, liable to fall immediately. He had to think of taking whatever treasure and household goods they could carry and fleeing in the Ioteru to Tyre or Gubla or some other Mizraimite trade-city in the north.

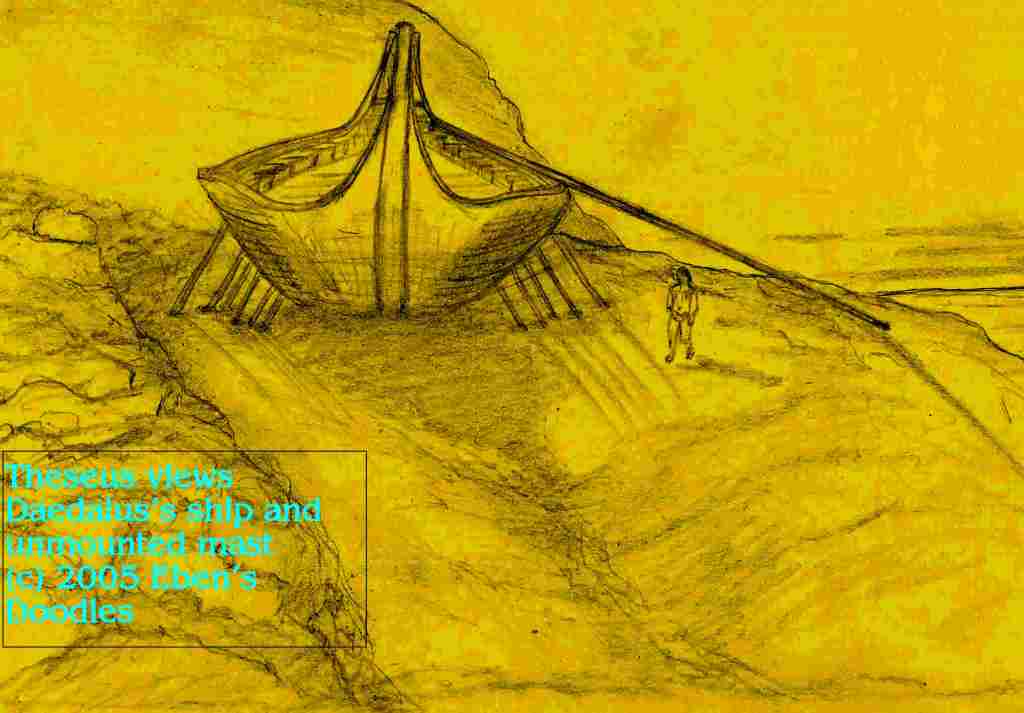

When Joseph first purchased the boat and invited him to go on board, it had exceeded the length of even a Hyksos warship and so seemed considerably over-sized for the use of his estate. How things had changed! Zenobia had filled it with her things and was looking for more space on board! Another sure sign was that Zenobia went to the trouble of having workmen rub the hull below the waterline with goat fat to discourage boring worms, and above the waterline shark oil was applied as a preservative, turning the pale wood a deep reddish-brown. Then Ramoseh went over every foot of the hull inspecting the fiber used in the sewing of the planks.

So it was with much misgiving he heard Zenobia ask one day to take out the ship, even to sail it on the River. He knew she was asking for a greater favor than a pleasurable cruise in the canals and river channels. She would not give him the reason for her going, and he did not ask. Would she tell him the truth? he wondered. He was not certain she knew her mind as yet. She had been very ill and was still mending. He had no reason to refuse her, though it meant the loss of the boat and perhaps the means of his own escape. The Ibbathans wanted his skin as much as Khian’s, and had become expert, from acquaintance with Hyksos methods, in the flaying of enemy hides.

If his wife were indeed fleeing, it might be just as well to let her go now as later when the Ibbathans set fire to the city, he reflected. If it had been his plan, perhaps she would have refused, and he would have had to remain with her. Zenobia was, whatever her mental state, a noblewoman. Potiphar would never cross her will once she had chosen to do something that lay within her rights as his wife and a high-born woman. If she had been, on the other hand, a commoner like himself, he would have instantly refused. In Mizraim birth was everything. A woman was even greater than a Grand Taty, Masgeh or Opeh if she were privileged--as Zenobia was--to touch the per-aa's scepter. Zenobia, he knew, could go to the throne room and speak directly to a per-aa and need not be called; he could not. He had to sneak in for private audiences.

Realizing he was going to be left behind, Potiphar resigned himself like an old soldier to his predicatable fate and watched, half-amused, at Zenobia's cheerful comings and goings to the quay, with attendants carrying a steady stream of furniture, stone jars of food and oil and wine, travelling chests full of clothes and money and household treasure, and whatever else she thought she needed for her "cruise" on the River. Potiphar began to wonder if the craft, however big and well-tacked-together (for it was built and outfitted in Tyre) with Mizraimite overseers would not sink from the incalculable weight of Zenobia's baggage.

It was almost more than Potiphar could swallow without protest when Zenobia appeared before him, announcing her boat was ready for her little ride on the River. Potiphar knew numerous, armed Ibbathan patrols were raiding Khian's shipping as far down as the River's mouth. But it was not her going and taking the falconship that so disconcerted him, it was giving up Ramoseh.

Let her take Assah her maid, he thought, glumly. But his overseer, who had proved his worth?

Instead of reasoning with him, the woman had informed him of her guilt concerning Joseph. She claimed his innocence at her expense. Then she announced she was leaving Potiphar for a few days, that he might be free to take Joseph from the prison and send him home to Ken'an in a chariot.

Potiphar did not like the sound of his wife’s confession. What if word got around that she had acknowledged making a false accusation against a steward? It was one thing to accept forgiveness from an underling. But to acknowledge wrong-doing to an underling went beyond the bounds of social decency and obligation.

Zenobia would not be reasoned with, he saw at a glance. He shrugged with the resignation of a veteran soldier, and Zenobia, after a pause to look at him, departed his rooms. He suspected she would not find Hazor, her old home, to her liking after so many years away. But why tell her and spoil what might be a nice journey?

Ramoseh, at her command, had outfitted the Ioteru with a new sail woven in Potiphar’s own outbuildings from zarah grown on the estate. Triple-layered, it was strong enough to take Zenobia wherever she had chosen in her heart to go. Perhaps they would sail to Tyre, disembark there and go by caravan to Hazir.

Zenobia sailed at dusk. He wondered why she waited for a late hour to sail, but recalled he had told Ramoseh the best time to elude both Khian's and the Ibbathan patrols had to be at eventide when the mists blanketed the Delta.

Old fancies also fly about at dusk. The moon had already risen when he thought he saw Zenobia standing in his rooms, though another part of his mind told him it could only be a phantom rising from his wine cup, since he had already watched her ship sail an hour before. Lying on his chair, he gazed at the apparition idly wondering if it were a wandering spirit or ka of someone from the ranks of the Dead; but it was too beautiful for that. No spirit could claim such eyes and full and perfect lips.

Tonight, as the moon filtered through the lattice of the upper windows and lit the likeness of Zenobia, her husband thought he saw the woman he had married in her youth: a ravishing form with perfectly-chiseled features, aquiline nose, and hair arranged like a queen's.

Presently, he was alone again. The bewitching moonlight, so warm and luminous before, seemed cold as it shone upon him. A beautiful, treacherous and troublesome woman was gone from his life--probably forever. A dream of a wife...a true wife she had never been.

Potiphar called out the moment she disappeared into thin air--as phantoms should. He fell back on his couch. As he lay awake wondering if it really had been Zenobia, or a figment of his wine-cup, the Ioteru rose higher round his empty, silent house.

Now what? Meanwhile, OP was decimating the Middle Universe in uncomfortable proximity to 3C 295.

Per-aa Khian himself cared little about Keftiu and left their ambassador to his latest Grand Taty to handle. The Per-aa considered he had more pressing matters than sending aid to a far-off island-realm, that however friendly and productive of luxuries for Mizraim in the past, was now only a beggar he could do well without. Besides, all state treasure was needed to produce war chariots and equip archers; Mizraim, at least what portion he still ruled, was not in need of Keftiuan baubles and playthings.

So the hapless ambassador departed Mizraim and sailed toward Miletus instead of his own land, which had been overrun by half-civilized, formerly tributary vassals, the Mycenaeans. Both he and his ship were seized at Ialysus on Ity, the Copper Island, by the Myceneans, leaving the Keftiuan king to face his troubles alone.

Suspecting nothing of the disaster in the north despite her recent telling dream, Zenobia set forth with Ramoseh, Assah, and other servants, some chosen because they had sailed with her on the River in the past and knew the boat well. Only when they stood out from the land did a reddish cloud begin to alarm them. A simoom approaching rapidly from the east, overcoming the prevailing wind, it spread across the bright, blue waters. Winds commonly blew north, carrying international traffic conveniently and easily upriver to Avaris and Nathasta (via canal), Ibbatha, and a string of cities that ended at Tammu of the first cataract. Yet the red cloud came from the southeast and furiously pursued Zenobia's boat as the oarsmen strained at their task.

Fast closing upon them, they found there was nothing to do but wait to see what it meant. In minutes the sea was whipped to a froth around them. Flying reddish sand so stung the women's eyes and skin they were forced into their shelter at the rear of the boat. The men battled to keep the ship running northeasterly and soon were struggling to tie everything down more securely before the gale swept everything overboard. Zenobia and Assah covered their heads in their robes and crouched against the blasts of wind that threatened at any moment to swamp the boat with towering waves.

The daylight was obliterated in the red cloud, and in a lowering dusk of dark-red stain the boat struggled to remain afloat, all the while driven far to the north and west, away from the coastlands of western Mizraim. For a day and yet another day the storm from the great Eastern and Western Deserts north of Avaris vented on them its full wrath and fury, until the Ioteru was barely clearing the high waves any longer, and the people aboard had all but despaired of life.

Sick and sleepless, the women huddled in their deck cabin, holding each other above the wet of the waves washing on board. Yet both were drenched and so benumbed they could not even feel each other's tight embrace. Despite all effort to keep the boat headed to the north, they were swept irresistably northeast, and were foundering when the red cloud and wind veered, rose, and flew round toward the East.

With bleary, bloodshot eyes the men watched the evil-appearing cloud sweep away, back toward its point of origin, leaving them with a sinking vessel awash with each wave that broke over the hull. Ramoseh and the men had prayed, and so had Zenobia and Assah, but it seemed that the cloud had departed only to leave them helpless to save themselves. After seizing a jar and emptying its glazed breads on the waters, Ramoseh frantically bailed water. Each wave added more than he could put back in the sea, and to Zenobia it appeared most futile. In their hopeless condition it was hard to believe Ramoseh when he cried out that he saw land.

All turned in the direction he pointed and they saw a high-towered mountain rising above the waves, white-peaked with ice and snow--things only Zenobia knew from childhood memories of the mountains of northern Kena'n. To them it was the most beautiful sight of their lives. Hope was reborn, and with hope renewed effort to keep the craft afloat long enough to reach the vision on the waters. Setting up the sail took much effort and cost them what strength remained, but the men succeeded; the Ioteru was coaxed into taking the wind. Within minutes the sea-washed mountain was steadily gained.

A surf rose on the craggy sides of the land, but they saw a small river and a sand bar breaking the force of the waves. It was very hard to maneuver the broken Ioteru into the little cove of the river, for they had to cross the sand bar and it was only cleared with much oaring and pushing against the bottom. At last they were driven over by the waves and the waters quieted around them. They drifted toward shore in a kind of trance, the lovely and peaceful river bank and olive grove seeming so strange after their disasters at sea.

Presently, they were at the shore, each thanking God in his own way for the breath of life and the sparing of their lives. Ramoseh and his men helped Zenobia and Assah down, taking the weak but over-joyed women by chair to shore and returning to gather food and personal things. Too tired to explore their little haven, they camped just above the shore under olive trees. Zenobia and Assah went off to a private place, but still in sight and hearing of the men. Assah took the needed clothing, bedding and other things. Ramoseh brought and set their "house" in order before she thought to rest.

Zenobia was silent, not only from exhaustion, for she was most angry with herself. She blamed herself for the calamity, since responsibility for the voyage rested with her. Yet she was too tired for self-recrimmination, and she lay down for long hours, thinking how much easier it would have been if the Eastern border had been open and they could have gone by caravan instead.

The Ibbathans! The thought of them was bitter, like the salt that still filled clothes and stiffened hair.

The weather was so mild the night passed without discomfort, and in the early morning Assah had just finished dressing Zenobia's hair as best she could when they heard cries of children coming up from the shore. Both women stood, looked for Ramoseh, but he was off somewhere, and the others were still asleep.

Curious, the two women stepped down to the beach by the river mouth and saw children running along the edge of the water. They were grabbing at what floated in the shallows, and were putting it in their mouths and eating. The children finished and ran past where the two women stood, and it was then Zenobia and Assah saw how starved they were. Ribs were sticking from their chests and their heads seemed too large for their necks and bodies. They could run like gazelle fawns and disappeared after glancing at the women.

Without the children it was again so quiet the hum of insects and the sound of waves breaking on the distant shoals finally told her something: there was no birdlife.

Assah went down to the water, reached and drew up a piece of bread. She hurried back to Zenobia to show her, and they both looked at each other with amazement. Walking back to the camp, they found Ramoseh had returned with dry branches for a fire. The flames had begun to crackle in the dry olive wood boughs when Zenobia first remarked on what was so strangely lacking.

"I hear no birds! Do you see any birds here?"

Zenobia was too mystified by the utter absence of birds to think of eating the simple fare he prepared. She began to look about and wondered. The land's mysterious silence only intensified, and she began to to grow alarmed, though Assah and even Ramoseh seemed comfortable enough with things, such as they were. She asked Ramoseh about the children, and he too had seen them, but only a brief glimpse and had thought nothing much about it. The land, wherever and whatever land it was, was inhabited but hardly civilized. Ramoseh confirmed her own impression in saying he was not sure it would be good to look for people. Perhaps the barbarians were not friendly to Mizraim, and until they knew better they ought to stay by their camp, repair the boat and set sail when it was again seaworthy and the winds were right.

Zenobia listened and nodded; Ramoseh, like Joseph, was wise and thoughthtful in his ways. The strange peace continued to bother her as she went with Assah to their resting place and sat gathering her thoughts and waiting for the ship to be made seaworthy. In this way she and her little crew spent most of the first day. Since they were secluded from the shore amidst trees, they did not see the line of people that slowly climbed down from the hills above and gathered on the beach, staring at the boat in the river. Strange but human chatter brought all the Mizraimites to their feet at once.

They peered out from the grove of trees and saw colorfully-dressed figures of four men and four women, all with long, dark locks of hair trailing on their shoulders and curling down their backs. As they watched, the men gathered what morsels of sea-soaked bread remained and gave it to the women to eat. There was little if anything left, for they searched for more, but returned empty-handed. One of the wild children was pointing to the ship.

Potiphar's wife had seen such men and women before. They were perfect models for the lively figures portrayed on pottery wares in which she kept cosmetics.

A man who carried himself with the dignity of a king appeared out of their midst. Eldest, with gray in his long, curling locks of hair, the older man took a step toward her and paused, leaning on an ivory staff.

Zenobia noticed Ramoseh and Assah gazing at the strange people with open mouths, but she realized all the foreigners they had ever known were market-people and traders. Realizing these people were high nobility such as herself, she knew they were expecting treament equal to their station in life. Astonished and dismayed that the gale should have brought her so far and to such a place as Keftiu, Zenobia was was at a momentary loss for the proper greeting to foreign nobility--when her people traditionally regarded all foreigners as barbarians, high-born or not. Was it proper then for herself, a Mizraimite noblewoman, to even speak with them, though their leader was obviously a great noble or even a king? The older man seemed to divine her hesitation, and smiled more graciously. "We are most grateful for your coming, my Lady, and for the elegant repast of bread that refreshed us, for I understand it was you who must have cast the bread on our waters. I recall an old proverb taught me by a maid in my nursery. It promises you will someday be blessed in return for what you have given to others. A charming thought, is it not?"

A diminutive duchess, no bigger than a child, began weeping. The older man seemed to lose his train of thought for a moment, then got hold of the Mizraimite tongue once again. "Forsaken of the gods, even our Lady Aspoth, we have suffered greatly here, as you can see." He was speaking a flawless Mizraimite, even to the complicated, archaic accents that determined one's class and standing in society.

Zenobia, certain their leader enjoyed highest birth, inclined her own head in turn. "I am the wife of Lord Potiphar, Captain of the Per-aa's Guard. I have come a stranger to your island and only because of a storm. We of Mizraim are grieved to learn of your misfortune."

Clearly moved by her kindly speech, the man bowed once again. The faces of the little group in his train seemed to turn brighter and less forlorn as Zenobia's greeting was quickly translated to the native tongue. The weeping woman fell silent, and the wild children crept out their hiding place. "We sent our ambassador to your court in Avaris," the man replied. "But after many days he did not return, failing to secure the help we requested. I suspect his ship was seized by our enemies. Do you not know our country has been destroyed by a shaking of the islands and the mountains in the Green Sea?”

Zenobia stared at the small man, who stood very dignified but no higher than a child in Mizraim. She wondered if he meant the collapse of a Per-aa's eternal house, which was a mountain. Everyone was still talking about Khian's mishap on the Western bank of the river. She thought that perhaps news had reached Keftiu as well. "How can the falling of one House of Eternity destroy your whole people and take away all their bread?" she wondered aloud.

The man did not smile this time. "I am not speaking of any trouble in your own land, but something you have not seen. It was the end of our world when it began."

Zenobia was well aware the little Keftiuan women were fast wilting in their ability to stand, but she had to know more. "What has done this to you? Please tell us."

The man's eyes wavered as he gazed at her. The people with him all shuddered as the memory of the catastrophe returned with overwhelming force once again. "Never has such a thing happened and never will again. You in Mizraim may see hunger when the great River does not rise to water your fields as it should, and you may also suffer when it brings too great a flood onto your land, over-running even the high roads and cutting off your cities, but here everything has been lost irretrievably. There can be no mending." He seemed unable to explain any further. "Come, let your own eyes see what some unknown, angry god, infinitely more powerful than our own god, has inflicted upon this people!"

He gestured toward the heights with his ivory staff and would have turned to go, but Zenobia called for more bread and wine to be brought from the ship and given to the islanders. After they had eaten and a supply was put in baskets and smaller jars to be carried, Zenobia turned to the dignitary.

"You have not told us your name."

"My name? Let it be lost to human memory. I was the Minos of Keftiu."

A youth boldly interrupted them, and Zenobia's brows arched in surprise, for he wore a kingly crown.

Crushed in expression, the young man withdrew to the others.

Zenobia looked after him, understanding growing in her mind. Yet so much remained strange and puzzling. She still knew so little that the expression on her face prompted the king to further explanation. "I confess I was ashamed to name myself to you. These people are my court, what is left. I sent everyone away to Miletus and Illios when the palace and city were destroyed along with all the others in my land, but these chose to remain with me."

He gave her a sad look that told her he must have intended them to seek their fortune elsewhere rather than share the misery of his fallen state. The doom that had become his lot was very real as she looked at their tattered clothes and wan faces. Bright and luxuriant groves of olives covered hillsides all around, but were a deception, she realized. As Zenobia and the king refused the two palanquins Ramoseh had brought from the ship, all walked slowly up toward the king's palace, over a series of low hills and flat areas that had been farmed but were now neglected. But the birds were still not singing, and the sense of doom increased.

And when she first saw the Per-aa of Knossos, or “King’s Town,” she was surprised because it did not appear, seen at a distance, to be ruined.

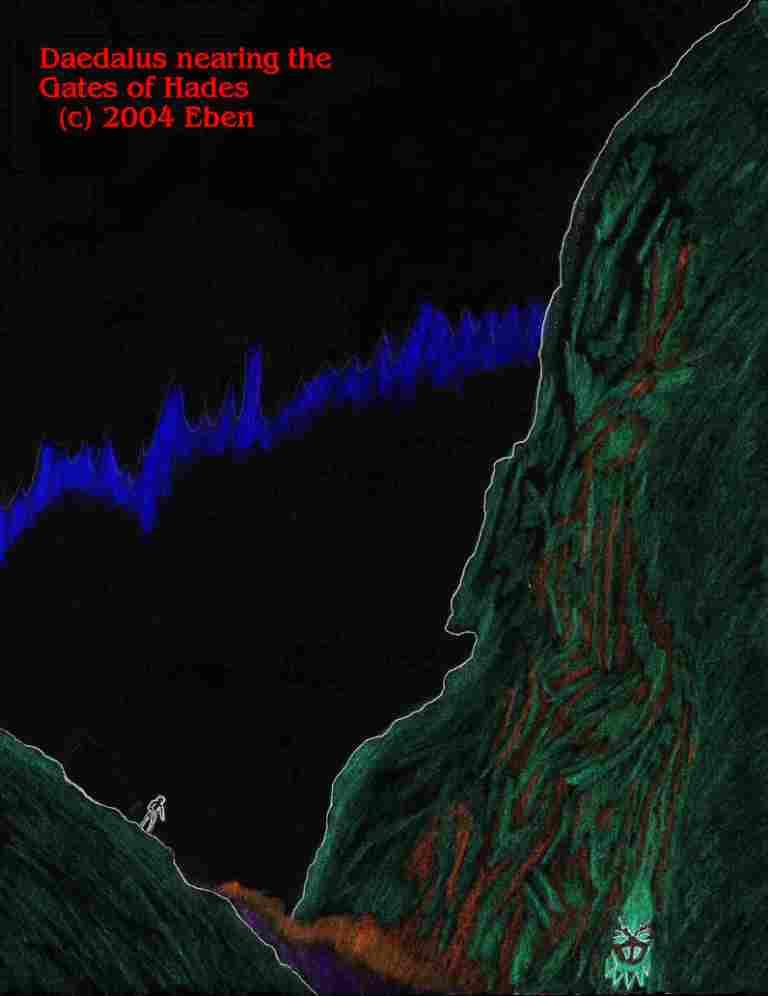

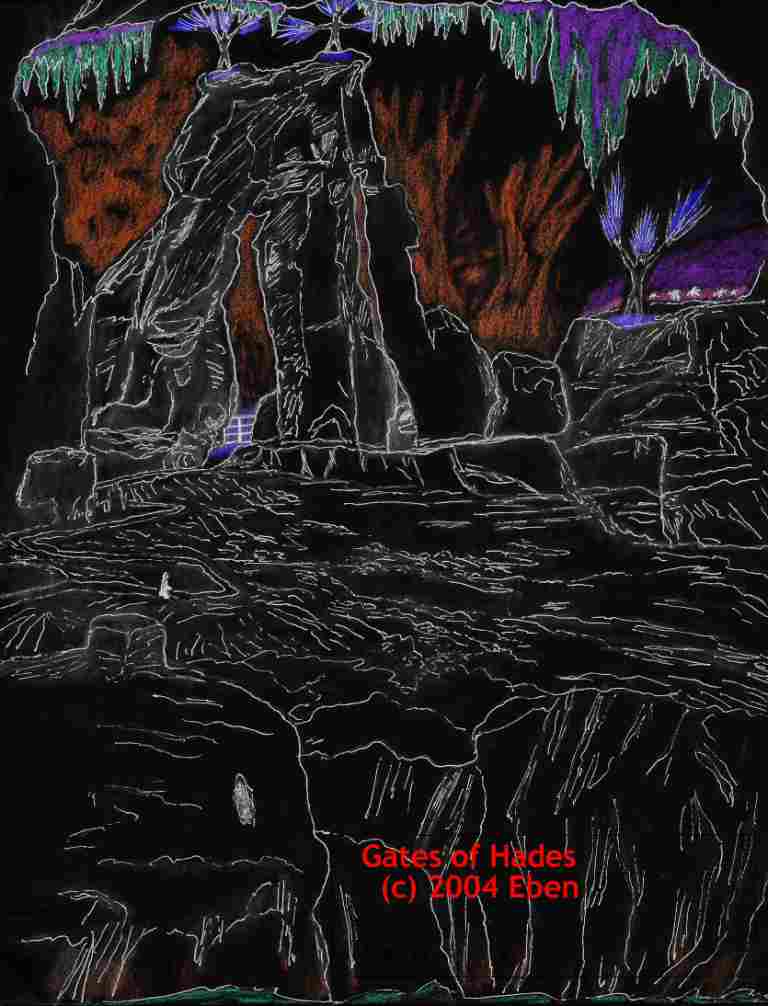

No one said anything as they came to the palace and stopped. As large as anything in Ibbatha or Nathasta, the labyrinthine palace of the Minos covered the entire hillside, and once contained a whole city with a king and a royal court within multiple, tiered walls, while beyond its gates clustered large mansions and the commercial and residential districts of commoners.

Zenobia looked about and saw a few people still sitting, scattered about among the ruins. The king followed her gaze.

"That is how we all were afterwards. But these will die soon. There is no food or hope or living in this place anymore. The grain and oil and wine vats in the store-houses are covered with great stones or smashed and empty. All our treasure is gone, but it was without use to us. Without our ships to go and buy food and bring back to the starving people--" He fell silent as they all glanced toward a lone figure that caught their attention.

Zenobia noticed the old man with flowing white beard and robe sitting by himself on a stump of a broken pillar. He was chanting something in old Mizraimite that the sorcerers of Nathasta customarily intoned in solemn voices, and so it sounded familiar to her. The old man never ceased chanting as she watched.

Just then Rhadamanthus II, the Dauphin Prince of Phaistos, came out of another chamber to meet her, having been told there was a distinguished visitor from Mizraim. Zenobia inclined her head to him, and he barely smiled, but his manner was most courteous as he spoke to her.

Zenobia studied him for a moment, but could think of nothing comforting to say except, "That is most honorable of you, to choose to stay by him at this time and afford him your care and solace, when you could have gone with the others to other cities and kingdoms and lived comfortably abroad."

The prince now bowed his head slightly to her, and said nothing more, so, the audience obviously concluded, Zenobia and her maid passed on.

Zenobia and Assah also saw the doors of workshops hanging ajar and fine craftsmen's tools lying on the floor among potsherds or smashed ivory and metal-work. Hundreds of such shops lay within the walls of the palace, but were already haunts of lizards, scorpions and poisonous spiders.

The king looked out toward the distant harbor, and spoke of the ships. "Mycenaean." he said bitterly. "My own queen and daughter went over to their chief when they saw our cause was lost. If you listen closely, you can hear the barbarians, rejoicing as they drink the last of our wine and make sport with our women. We were powerless to stop them from flooding in after our navy was broken on the rocks by the mighty waves and cast in pieces, with their crews and admirals, all along the north shore."

Zenobia felt a surge of outrage. She could see with her own eyes how refined and gentle the people of Keftiu were. How could the barbarians take such advantage of the stricken king? "Where is your army?" she asked. "Why not fight them and push them into the sea?

The king smiled grimly. "We never had a need for an army once we moved the capital here from the harbor. Our realm was always safe in the cradle of the Green Sea as long as we had a great fleet and navy. Can you not hear them?"

Zenobia heard the sounds of revelry coming from the massed ships in the harbor. It was the noise and hubbub of a multitude, such as worked on a Per-aa's eternal house. A mountain breeze off icy slopes must have reached her, for she suddenly felt chilled despite the sun. Cool linen, she realized, was not proper wear for the climate of Keftiu, which had not the warmth of Mizraim's deserts.

"We need to go now," said the king. "They will send their men out again soon for more gold and women, whatever they can still find among the ruins of the cities, and they will attack us if they find us."

Quickly leading the way, the king showed Zenobia into a hidden room, buried beneath rubble, deep in the maze of rooms and halls and courts and ruined gardens. They stopped to catch their breath, and Zenobia looked at murals of young men leaping over the backs of bulls, the brilliant colors gleaming in the illumination from a deep light well. "How long can you stay here and live like hunted animals, without a place to lay your heads at night?" she inquired of the king.

The king had sat on a stone chair where Pasiphae his wife, the Mina of Keftiu, had once presided over her own court of a thousand noble ladies. He gathered the folds of his torn but regal robe.

“It is my fate to be here until they find me. They will have some difficulty locating this place. I know they realize I am still here somewhere, and it is only a matter of time until they discover us; but I have no place to go."

As he spoke, the tattered remnants of the king's court gathered close at his sides, all facing Zenobia and her maid and her men-sevants. He thanked her again for the bread and wine, which Ramoseh and his men, together with the king's courtiers, had carried all the way from the ship.

Suddenly, all that she had been shown rushed in on her with full meaning, for her life too had seen utter ruin. She glanced at Assah, and her eyes too were filled with tears. Zenobia bowed to the monarch.

"My heart is overwhemed, but I cannot stay, Your Majesty. As soon as my ship is ready, I must continue my journey, for I have a grief in my own heart and wish to return to my natal place."

"Yes, I understand. But, my child, be careful not to be seen when you return to your ship. You were most fortunate you put in at that small place on the little river rather our main harbor."

Zenobia, addressed as "child" by the Minos, was not offended. She was strangely affected by the grave dignity of the little king. She bowed again and then would have taken her leave, but the Minos had something to ask her. "Would you keep absolutely silent about us, what you have seen here? No one will help us, not even the Tyrians whom we established in their island long ago, and so our enemies need not know our end."

Zenobia waited, for she thought she sensed the ruler wished to impart some last word to her from the treasure-chest of the ancient lore, an inheritance from which he was the last to take anything out.

"Tell them Heaphes our supreme god has died. We the living will soon lie with him in the dark underworld."

The Mizraimite in Zenobia was profoundly shocked. How could a god die? She had been trained since a child to believe that gods were immortal.

"Tell them," the Minos repeated. "He was born aeons ago in the Caverns of Dictys. But when you go, look into Heaphes's natal temple on the hill above your camp. Let the Mycenaeans laugh, who came to see what happened but have stayed to destroy us. They have a temple to Heaphes, they say, and their god is not dead. He is only a copy. I tell you the truth: great Heaphes died."

The last words of the island king echoed in Zenobia's ears as she and her people were shown out of the palace by the king's son. When she saw the light of day again, reason and sense seemed to return to her as well, and she turned to the young man, who told her his name was Daedalus.

"Tell me, why has this all happened. Do you know?"

Prince Daedalus’s eyes clouded for a moment and his face lowered. He gave her a sharp look when he again looked up. "I can tell you what my father has said. He said only to my hearing to tell you how we may have offended the Lord of All. It happened with us as the strange, green-painted old man and young woman from some eastern, desert country lately warned--if we did not change our ways and cease neglecting the poor, they said all our towers would be mown like spring grass and cast in the fire. Now you can see we should have listened when there was still time to save ourselves!"

As though he again saw the old man and the woman and the little, frightened birds that were always fleeing into their hands, the prince shuddered, and released a deep sigh. "But they went back to their own country when we harassed them with our chariots from going freely about in the villages, and what they said was disregarded until now. They said it was wrong to take the Most High God's name in vain and fashion others of stone and ivory and gold in his place; and the woman also said our understanding would darken and we would do many evil things. My father says now their words were true of us, and this is why all this has happened. Yet I still do not understand. None of our own wise men remain alive. Can you explain what the strangers meant about us being mown as grass? Our wizards and sorcerers all said nothing adverse would happen. If any divine "mowing" or "shaking" did occur, it would be for good, not ill, and our palaces and cities would spring up in greater splendor than before."

Listening to the prince, Zenobia knew she could not yet speak about such things with assurance. What would Joseph say? she wondered. "Since your own god is dead, I will pray for you, to One who is still alive, the Most High God."

The prince looked at her with surprise.

"Do you know this god they declared to us? Tell me about him."

Zenobia then shared the story of Joseph and how she and her people had come to know his Almighty and Invisible God.

The prince was silent for a time. He was shaking his head. "Could this be the same merchant whose ships brought such fine things to our land?"

Knowing something of Joseph's enterprise, Zenobia smiled. "It is Joseph's ship that I sailed to come here." The prince sighed. "We inquired of the sailors and captain, and they told us tales of this great steward and the god which brought him mightily out of his own country to Mizraim, after his treacherous brethren sought his life. This, then, is the same man you speak of and you must be--” He swallowed back his words, bowed quickly and ran off to tell his father.

"You spoke well to their king and his son, as Joseph would, my Lady," said Assah in a quiet, admiring way. "They do not know the ways of Joseph's God, which would save them in their distress and bring back prosperity. Without Him there can be no recovery--in that they are right. Can’t you tell them?"

Zenobia looked away. It was the greatest pain that she knew what the prince’s look meant. Was it as simple as Assah thought? she wondered. After all, Joseph's own life was a mystery which only his God could explain. In the midst of the storm and now facing the Keftiuan's despair, it was made plain to her that she did not yet fully know the God of Joseph. She realized she had much to learn about the Lord of All. Knowing her own lack, she had felt the young prince's sorrow and perplexity touch her own troubled heart even while his recognition of her drove into her like a sword.

They were careful to look out for the Mycenaean chariots and cavalry as they left the palace and walked back down toward the south coast. Zenobia turned to Assah, when she noticed her maid's questioning look. "I only wish I could tell them about Joseph's God, but I do not think I have the words that would make them understand such a One. After all, you know how he has dealt with Joseph. Who can explain for him? All they have known is their own gods, and now the chief of them is dead. I feel very helpless here, Assah." The maid was surprised as her mistress confided more of her misgivings.

"Do you think we can know Joseph's God? He seemed so powerful and active in our own country, but here--" Zenobia broke off, looking at Assah helplessly.

Assah gave her a reassuring smile.

"One thing I remember clearly. I too wondered if Joseph's God was only for his Hebrew people, and I asked Joseph about it and he said God had spoken to his great-grandfather Abraham, saying, 'I will bless men of every tribe and nation who trust in Me."

Zenobia sighed with relief and said no more. They both thought of Joseph's God and marveled at his ways and how He brought them so far across the sea to a broken people, just to witness such great need. Was that His only reason? If not, what else was there?

Zenobia pondered the question. On the way back, a mud-brick hovel that was deserted when they first walked by now showed it was occupied by some household things scattered about the doorstep. Leaving the road (which was over-grown with weeds from disuse and lack of wheeled traffic), they went over to the crude dwelling. A thin-faced man peered out with great fear. They could not speak to him, as he did not know their tongue, but Zenobia had Ramoseh set down the baskets he and the men were carrying back to their camp. Each basket held only a few loaves and a vessel of wine for lunch, but Ramoseh obeyed his mistress gladly. The man understood, and his fearful expression changed quickly to one of hunger and need. He stepped out, and a child's dirty face appeared at the door, followed by his mother, a tiny, dark-eyed woman with a sickly babe at her breast. Blinking away tears as he went over to the baskets and gathered them together, he took them to his wife and together they greedily ate of the little loaves, tearing off pieces for the toddler at their feet. Impulsively, Zenobia went over to the wretched family, stripping off her rings and offering them in her outstreched hand.

The man and woman stared with incredulous eyes. Then the woman disappeared in the dim hovel and brought back out a very fine vessel of painted pottery. Lifting the lid, the woman's tears fell as she held it up to Zenobia's gaze. It sparkled and glittered with jeweled rings of gold and silver and electrum. With a bitter smile she poured them on the ground, and the little boy laughed and began playing with the bright things. Zenobia backed away, staring at the people and then at the great wealth cast out disdainfully on the ground--useless in a ruined land. Despite all their riches, they starved!

Stopping at the hall of the temple the king had said to visit, they stepped beneath displaced stone bulls at its outer gate. Inside the ornate, bronze door, which had been hacked with the same double-headed ax held sacred in Knossos and Mycenae, they found a deserted and desolate sanctuary and fallen masonry everywhere. In the gloom of the vast building they heard water running from shattered pipes for the Keftiuan priests' ritual lustrations when they came to offer rich gifts of Mizraimite electrum and gold and jewels (all won in trade) to the god. They stepped over pieces of the ceiling's painted murals and broken pottery and priceless ivory-work. And at the end of the hall they paused and fell silent, for it was as the noble king had said: their chief god was dead. The form of marble and gold and ivory-work that had once stood proudly and held a an electrum thunder-bolt was now a heap, a confused mass of huge legs, arms, torso, and--at some distance--a severed head with a smashed nose lay staring upwards.

Ramoseh, made to look small by the giant head, reached up to point out the looters' marks, tell-tale signs that a crown had been pried away with sharp blades.

Grateful of the fresh air, blue sky, and the beauty of silver-gray olive trees and red, poppy flowers, they returned to the outdoors and slipped quickly away into the shelter of the ancient groves of their secret campsite. Though Ramoseh set watches during the night, no one could sleep any more in that doomed land. All night Zenobia sat on her blanket-and-mat bed, haunted by the scenes of the king's palace and capital. But what kept her most awake was the sight of the head of Heaphes, torn off and lying with a smashed nose.

In the early morning, the wild children came again, crying woe to one another when they could find no more bread cast up by the waves. But Zenobia was waiting for them, and gradually their hunger overcame fear and the tiny, olive-skinned creatures crept up to take food from her hand. Yet if touched by her they fled instantly away like the birds that had forsaken Keftiu. Though always famished and never filled, the children were bright and lively as the colorful birds on the Keftiuan's pictured vases. Their merry, brown eyes and curly, black hair and dark, reddish-brown skins were a great contrast, however, to the wan, melancholic expressions and fashionable hairstyles of the lost nobility and their king.

So taken was Zenobia by the cheerful spirits of the orphan children, she regretted to leave them when the Ioteru later set sail in the night, on the wings of a strong wind coming down from the mountains. Knowing she would never return to see them grown to men and women, Zenobia left behind a large store of bread and sweet-meats near the shore where they would be sure to come. Clothing, she knew, was yet of no use to such wild things.

Approaching closer to the Mizraimites' haven, the Mycenaeans conducted new forays, sending out chariots and horsemen from King Theseus's fleet in the main harbor on the southeast coast. Most of the coast was poor and had no cities, not even ruined ones; and except for a temple they had already raided there nothing they knew of to detain them, so they launched a final attack on the king's palace without bothering with Fair Havens.

Zenobia's ship was safe beyond the horizon when Mycenaeans began torching the olive groves around Knossos in case the king tried to escape from his covert into surrounding country. A detachment was sent by the clever Mycenaean ruler to cut off the Minos's escape to the south. He also sought to secure the Mizraimite ship at Fair Havens of which he had just received a report. Finding no ship in the little harbor of the river, the Mycenaeans returned to the temple on the ridge above. Growing weary standing guard and throwing stones at lizards infesting the ruins, the Mycenaean troops began to make sport of the Keftiuan temple. With much laughter they rolled the head of the "false Heaphes" through a hole they knocked in the wall.

The head continued to move once it gained the steep slopes behind the edifice. Soon crashing down through the olive groves, the head bounded up into the air and cleared the beach entirely before dropping into the open sea with a great splash. The wild children, drawn back to the campsite by the favors of the stranger they called the "White Goddess" or "White Lady" because of her hair were the only ones who saw the head roll into the sea. They all jumped with surprise and then began laughing. They had seen the men from the ships do many odd things in the area and gave it no thought at all.

Thickening clouds of smoke from the burning of royal Knossos and its environs poured up into the heavens and could be seen far out to sea, obscuring the sky as the Ioteru sailed eastward toward Tyre.

"They chose to stay in that terrible place," observed Assah to her mistress as they watched the smoke-columns tower like the benben-pillars in the court of Narmer's funerary chapel.

Zenobia agreed. "They could not leave, even when their hope was gone. Now why should such civilized people desire only death and ashes?" For a moment forgetting the great abyss fixed in that day between maid and mistress, slave and noblewoman, the two women stood with arms entwined, as a darkly flaming island smouldered and sank beneath the horizon.

"The children," said Zenobia as she gazed upon the barren waves. “The children--”

“My, she has changed!” Assah reflected, thinking how her mistress had once claimed to hate the very thought of child-bearing and children of her own.

Despite Zenobia's protests, that she had no intention of selling her servants, the man would not be put off, and she was forced to pay a tax on the head of Assah and Ramoseh and the ten rowers she had brought from Mizraim. They are all thieves and robbers!" Zenobia complained to Assah, when they were at last free to proceed. "The rascals assume I am some ignorant foreign woman, who does not know them and their ways and cannot complain of this to their king!"

Accustomed to Mizraim's wide thoroughfares and public spaces, Tyre's warrens and tenements seemed at first impossible to penetrate. Ramoseh and his men were carrying both Zenobia and Assah in the palanquin, but they were soon jammed between the walls of towering tenements and the cargoes stacked high on the heads of human porters. Twisting, dark byways quickly led them astray, and the king's big, white-walled palace had sunk completely from view. Seeing they were lost, Zenobia ordered the palanquin set down. At once she was mobbed by a horde of ragged, dirty children, all demanding silver pieces.

Ramoseh moved to push them back, but Zenobia picked out an infant and held him up. Its mother rushed up, and with incomprehensible language yet indicated her pleasure that a noble lady should take interest in her latest offspring.

Gazing with misgiving at so many children, and so much dirt, Zenobia called for pieces of silver to be distributed. It was a dangerous undertaking, she knew, for all the glum-faced, lounging beggars in dooryards looked to be murderers and thieves and their tawdry womenfolk no better. Yet they had no trouble, and the parents of the children claimed their offspring immediately, dragging them protesting away from the Mizraimites. Disgusted at the sight of pillared temples and marbled mansions rising high above running, open sewers where swine, dogs and naked children swarmed, Zenobia determined to get her business accomplished as soon as possible.

"I will speak to the Chief Cupbearer for you," said the palace aide to Zenobia in an ante-chamber of the king's palace. "But you must leave the slave girl here."

Zenobia gave Assah a a startled look. Having found the palace after so much difficulty and danger to themselves, they could not be separated.

"I will await you here, my Lady," said Assah after a moment's stocktaking, when she saw how reluctant her mistress was to part. "The Lord God will take care of me."

Her eyes glistening, Zenobia put her arm around her maid, and then gave into her keeping richly-jeweled bracelets. "Assah, I know these people and that we have landed in a den of cut-throats! Take these things to pay for your return to our own land, if I do not come for you in good time."

Bowing with a cold smile, for he knew their Mizraimite tongue well, the Tyrian showed Zenobia to a more richly-appointed inner room. The aide hurried through high, double doors into the chamber of the king's chief cupbearer. The official was sitting on a throne-like chair of Keftiuan ivory-work turned toward the sea. Behind his head light-blue waves broke and sunlight glinted off a mass of shipping that stretched across the water to the mainland.

The portly, thick-nosed figure uncoiled from the chair set before the high window. He turned to face the aide. His purple gown covered all but the gold tips of his shoes and extended to a high, carnelian-crusted collar. "What do you mean?" he said. "Who is this Mizraimite woman that she insists on seeing the high god Dagon the Thirteenth?"

The aide was wiping his brow with a fine linen cloth as he tried to explain. "Exalted One, I can only say what she told me, that she is the wife of a commander of Per-aa's palace guard, and has a greeting for the--"

"I cannot let her into his divine presence," the Chief Cupbearer hissed.

"To the king I bring greetings," declared a foreign voice in perfect Akkadian.

The two men spun about to face the intruder.

Zenobia strolled into the high-pillared chamber.

"I have just come to this city. In Mizraim's south harbor I left my ship, the Ioteru. I am your guest and your humble servant from Per-aa's court. How can you refuse me the courtesy of giving my regards? I have come far through dangerous storms to give gifts in the name of the Per-aa of the land of red and black!"

The Chief Cupbearer stepped down from the dais on which his chair stood and regarded her a moment. "But madam, I am not the one you seek," he began, touching his fingers together tentatively, and drawing a long breath through a huge, hooked nose. "The god cannot receive the supplications of pious and well-meaning pilgrim; however, I will inquire of him and let him decide the matter."

The Cupbearer's aide slipped discreetly out of the chamber by a door that closed almost invisibly in the paneled wall.

"In my country your harbor master would be whipped like a dog!" she began. "He forced me to pay the king's tax on my own servants, all whom I never intend to sell!"

"I shall certainly inquire into the case," the Cupbearer hedged.

"And then there are all those men in your streets, begging for bread, their children scraping the gutters for scraps of food! What about that? In my country no one starves. There is always food for the people."

"Oh, my Lady, you must be talking about the porters and their families! They produce too many children. We cannot possibly employ so many, and most that are able to work refuse to do any worth-while labor to support themselves. It is useless to try to help such rubbish! As for the children, they grow up just as worthless!"

The Cupbearer and Zenobia eyed each other for a moment after this exchange.

“You have food, why don’t you distribute some of it then? It’s useless demanding work out of them if they’re too weak and starving to do it. I saw them with my own eyes. They must be fed if they are to work!”

The Tyrian thought it best not to say anything more. Why try to explain the market and how labor prices were kept low and profitable? Women of the land of red and black were proverbial, even in Tyre and Gebal and Zidon, for the ferocity of their tempers when crossed. The door opened a crack, then fully, revealing a dim, torch-lighted hall. The Chief Cupbearer motioned for her to proceed, and together they climbed the passageway and numerous steps to the audience hall, situated on the fourth level of the palace. As Zenobia walked along she glanced at the the Kushan leopard skins, gold Keftiuan axes, purple Tyrian brocades, and choice pieces of armor and weaponry from Mizraim, Tartessus, Punt, even various barbarian islands.

"I see you have Keftiu represented here," Zenobia remarked. "Do you know how terribly they are suffering from the recent Great Shaking. Not a single building was left standing or undamaged. Or don’t you care about that either?"

This too the diplomatic Cupbearer would not answer as he hurried ahead of her.

As Zenobia came before the divine personage titled Dagon XIII, who was sitting on an ivory throne carved like a peacock's fan, flanked by several rows of colorfully-dressed courtiers. When she had bowed, the divine king made a sign for her to come forward to speaking distance.

Zenobia gazed upwards at the gorgeously-attired figure but it showed in her eyes that she was not exactly overwhelmed, having seen too often a supposed divinity on the throne to be overly impressed. "My greetings to the king," she began.

This particular god-king--a rather young, tender-cheeked man with large, soulful eyes and the prominent, beaked nose of his race--shrugged at her impertinence. Strangely, the pilgrim had declined to address him as a god, which meant he had to go without the usual litany of up to a dozen titles.

"Your Celestial Majesty, I have come an an errand very important to me. I have little time. I must find a caravan at once to take me to Hazir, my natal city, and thence to Kena'n."

The king rubbed the soft beard of his face with a beringed hand. Despite her brusque manner of greeting, he liked a person who got down to business without a lot of unnecessary words and flattery.

"Yes, yes!" he said. "He's the one, Meshullam by name. I mean, I can help you after all."

He etched something on a wax tablet, stamped the missive with his signet ring, and handed it briskly to the Cupbearer, who tendered it with a gracious smile to Zenobia. "Give this to the man in the outer chamber, the one who handles protocol. He will put you on the first caravan to Hazir, with a man I know from many dealings--and rather sharp ones, I must say!"

Zenobia took the tablet and her manner softened and she bowed. "I am most thankful to you, and will pray for you when I come to my native city."

The god-king’s mouth fell open. "What do you mean 'pray' for me? You may need your own prayers, since this particular trader employs rather strange and wild animals as his beasts of burden."

Zenobia's eyes took on a faraway, softer expression, as if she were looking again on the waters of the Great Sea, believing that God would make a path for her on the water. "I was referring to the Most High. Do you know Him? He is invisible, but beside His splendor all visible gods fade to mere powerless shadows."

The ruler looked at her with more of a startled countenance. "Are you mad? An invisible god? What is Mizraim coming to? I have seen a man saddle a wild camel and attempt a ride, but I have never heard of such a thing as this god of yours!"

Zenobia smiled. "He is not a god like others. A few years ago I would not have believed in Him. Yet He exists, and I have learned he is God over all the gods, who are mere figments beside him, if they have any existence at all."

"You have seen this great God then? I thought you said He is invisible."

The king's eyes shone with undisguised wonder as he examined the distinguished-looking, emerald-eyed woman before him. Could she be such a fool as her words made her out to be?

"Yes, I believe I am seeing Him, more and more, but that is a thing I have no time to tell. Perhaps when we meet again, Your Majesty." She bowed, thinking it was time to leave.

The sea-king made a little cough and made no sign of dismissal. "I am sorry to detain you," said the king, color rising in his perfume-oiled, somewhat swarthy cheeks. "Did you not tell my Cupbearer you had a message from Per-aa Khian for me, and, er, gifts?"

Zenobia looked at the king and paused. In her mind's eye she still saw a flaming island. She looked down at her hand. "Indeed, you are deserving of something, if you do not mind an old heirloom of mine, a stone Mizraimites regard as unfashionably foreign at court." She stripped off a ring with an emerald in a gold setting from her finger.

The monarch of the waves's thick lips smiled as he watched her remove the signet (her father's and a gift to him from a Hyksos Per-aa before Khian) and extend it toward the throne.

"I must ask one more favor of mighty Tyre."

Dagon was startled by the urgent note in the woman's voice, but he straightened up immediately.

"Say!"

"Fill my ship with food and send it immediately to the Keftiuans!"

The monarch’s face flushed red and his eyes glinted at her. "I am sorry to hear this from you. I have no love for them, even in their distress. There can be no forgiving how they oppressed us with stiff duties on our goods--in exchange for theirs--for centuries, so that we were their bond slaves, living from hand to mouth while they were all kings, from the lowest potter and copper-smith to the Minos himself. The gods are just and now the situation is reversed. We would have it remain as it now is. Our city is a queen safe in the midst of the sea, and no one can attack and cast us down from our royal seat--pre-eminent forever! You’re asking us to give up our favored position. No! They are our mortal enemies! We Tyrians never forget!"

Zenobia remembered the starving couple in the roadside hovel and the roving bands of children and stood firm in her request, demanding once again a ship to be sent. Her green eyes began to flash, as if a storm were about to break. Finally, the king, eyeing the emerald and all the electrum, sighed and wrote something on a wax tablet, adding his royal seal.

After letting go the valuable electrum--a king's ransom--for a cargo of grain, Zenobia was shown out to the protocol minister, the Chief Cupbearer's aide. In his chamber Zenobia found Assah, Ramoseh, and her other servants. They left the palace with the minister, who personally showed her to the king's quay where the royal barge lay at anchor in the Harbor of Mizraim.

"But perhaps you would like to go in your own craft. It's just a short distance to the mainland."

Zenobia glanced toward her ship, resting amidst the clear, blue waters.

"No, my vessel is to make a journey to Keftiu and then return to await me here. But I must call my retainers and oarsmen. They will bring my things on board. Whose ships are those over there, the ones with the lions on their banners? Their sailors appear to be barbarians by their speech and behavior."

"Mycenaeans, my Lady," corrected the aide gently. "Of course, since the shaking of the islands in the Green Sea the Keftiuans have had to give up much to their Mycenaean allies. Myceneans bring us many fine things from there for trade--ivory-work, pottery fit for a king's palace, shiploads of Keftiuan maidens and such; even a crown fit for Heaphes their chief god!"

“All stolen goods, if you don't know!” Zenobia shot back at him with old fire.

After Zenobia's servants and her belongings were on board the royal boat, the Cupbearer's aide gave an order. Thirty Keftiuan slaves who sat below deck, many of them former high officials in Kenftiuan society, began to row the boat methodically under lash to the Tyrian suburb on the mainland. As Zenobia and her servants were taken in haste to the linens mart and staging ground on the city's outskirts, the leader of a caravan she was seeking was wasting no time.

With the harbors as a center of sea-trade, here on land lay the throbing heart of Tyre’s land trade. Where a vast concourse of donkeys, traders and merchants milled about doing business, Meshullam checked his own caravan to see if everything were in order for an imminent departure.

He was in fine fettle. He had concluded a good round of trading with the king himself. All his precious Mizraimite linens and Kushan ivories had been disposed of at a hundred times their original cost in Kush, Nubia, and Ibbatha. Humming a popular moon-god psalm extolling Larisharphim's bounteous love and care of mortal men, the newly rich Ishmaelite busied himself with a last pull of a goatskin saddle, assuring that the particular load was balanced for the getaway up the "Ladder of Tyre."

He glanced at the camel he had finally trained to carry his over-sized chest of valuables. It included the new robe outfitted in Nathasta with golden charms for the king of Hazir. Joseph had never returned his robe, since it had gone with him to the Mizraimite's house.

Meshullam sighed at the cost of its replacement. Yet he had made up for it with the king of Tyre's acquisitions. As for charms festooning its fringes, he doubted whether they would help the king much against the troublesome Hebrews. It would take more than charms to get round the House of Jacob, he thought. His sharp eye caught sight of the king's minister before the man even saw him. the old fox’s brow noticeably darkened. He waited for the bad news; news that, for example, the king had received fresh intelligence concerning the original price of his purchases and was demanding his head as compensation. And he had already experienced some bad news that day--this new tax and that tax, involving much delay and haggling over cups of lager beer with the king's administrators before bribes were accepted and the worst of the taxes defrayed.

"My lord, you were not thinking of leaving at this time of day?" the Cupbearer's aide cried. He stared with misgiving at the loaded, irritated camels that were spitting streams of green cud at hectoring passers-by. Sidestepping camel dung, he hurried over to Meshullam's side.

"Morning of fragrance!" he beamed with the customary greeting, though the aroma of donkey and camel droppings had so far advanced as to be stifling.

"Morning of light!" Meshullam replied just as absurdly, spitting to one side with irritation at the man's intrusion.

He glanced beyond the bowing cupbearer and saw the Mizraimite women and their servants, and immediately his eyes narrowed.

The Cupbearer's aide eyed Meshullam as he handed the royal tablet over.

Meshullam's brows arched as he read the message, inscribed in Akkadian-- trader's tongue. Without another glance at the women, he nodded stiffly to the Tyrian. "I will take them only because the king, so dear to me, er, heart, has requested it. They can have the camels I recently trained to take excess baggage and the heaviest things, and two surplus donkeys for whatever else they have with them. Fortunately for them, I have little left to trade and can put my big trunks on the backs of my donkeys."

Meshullam spat again like a camel in disgust at being delayed, then darted off to speak with his brothers about the change in loads. The Tyrian conveyed the good news to Zenobia and Assah, waiting at the edge of Meshullam's camp. Meshullam motioned to his youngest brother. The young man grumbled but went to help Zenobia's men set up for the night in several tents, since precious momentum had been lost and it was decidedly too late to negotiate the Ladder of Tyre.

Zenobia stood talking with Assah while they waited. Presently, their little tent ready, the two women secluded themselves for the night, while the more entertainment-minded men, joined by the friendly Tyrian, talked long into the evening and chewed pistaschio nuts and shared solemn sips of the Tyrian's supply of Lebanon's fragrant wine.

Before the huge, lowering crescent moon had given way to the dawn, the camp began to stir. The same young man, though like his brothers a bit unsteady in his steps and like a camel in his breath, hastened to help Zenobia's men load up properly and pack the tents away. In short order, the well-prepared caravan and its foreign addition was ready to strike off. The merry-eyed, young Ishmaelite, looking to Assah's eyes like Meshullam must have appeared in extreme youth, hurried to help the two women mount.

Zenobia and Assah, however, stared at the camels, wild things of which they formed no positive opinion, then at the donkeys all Mizraimites considered abominably unclean creatures, and finally, with extreme annoyance and disbelief, at Abdullah. Abdullah sped off to Meshullam, who came running, his scant beard jerking up and down. As he skidded to a halt, he hiked his garment as if to gird his loins for the fray.

A heated conversation began between the old trader and the Mizraimites; finally, most reluctantly, the two women took their place by the still recumbent camels. Sooner would they die on a camel's hump than throw away all dignity and honor on a donkey. How Mizraimite of them! But it would be a long walk for Zenobia's servants, who were not to be humiliated by either camel or donkey. They were glad of the chance to stretch aching muscles, having come so far in cramped quarters aboard ship.

"Their chieftain doesn't like to talk to women," observed Assah quietly to her mistress as Meshullam passed by during a final inspection, for his camels had been known to thrown off baggage and bolt if they felt so much as a pin prick from a burr.

Zenobia laughed into her hands. "I've seen many of his kind and bought their watered mare's milk for twice what it's worth. Yet they always snort and grump about when its women who line their pockets with gold--as if they are doing us a favor by fleecing us of a fortune!"

The now well-travelled Assah laughed with her. "My lady, traders are so alike the world over, always demanding a high price for their goods, then giving something of lesser value in return. Yet somehow this chieftain seems different from the other sand-ramblers. Perhaps, something else is bothering him."

Finally, at Meshullam's signal, the groaning camels enlisted to carry the ladies were made to rise, and in a few minutes the caravan was leaving the never-quiet environs of Tyre's Old City on the mainland for the long, arduous climb up onto higher ground where an old road called the king's highway ran eastward. It connected with trade routes of the Syrian desert and the kingdoms in the north and northeast.

Typical of his kind, the Cupbearer's under-secretary stood bowing toward Meshullam and the two ladies as they passed by toward the first, well-worn rung of the "ladder."

As soon as he docked at the island he found the whole city cast into panic and confusion. The Temple of the Moon-god Dagon had shaken and collapsed, instantly killing 1,500 sorcerers convened to deal harshly with cults, particularly the rise of the dangerous Jacobites of Hebron who had reduced Shechem to ruins. Only the temple and Dagon’s temple image were destroyed, though not a twitch of the earth was felt beyond. As for Dagon in the flesh, the god-king, he was found by his Cup-bearer crawling on the floor of the royal bedchamber, absolutely terrified by the news and the thought he was next.

"Why are these Kena'nites so eager to please us?" asked Assah as the figure of the portly Tyrian was swallowed in the dust of their train. "Yet when I waited for you, my Lady, in the palace, I felt I might be robbed and murdered the moment I finished the tea they brought me."

Zenobia let Assah her friend chatter as memories flooded her mind. She saw the Tyrians again in her father's palace in Upper Hazir. How they bowed, far too much, and smiled, again too much! They were merciless traders, however, when the business commenced.

She might have told Assah how her own father, a brilliant man, with diplomatic skills, had perspired before the annual trade treaty was concluded and signed with his signet. Yet once that was done, the Tyrians were all smiles again, bent on enjoying Hazor's fabled wine, women and song. The people, especially tavern-keepers and Edomite dancing girls, were sorry to see them go.

Yet she had divined something wistful in the king's eyes when she mentioned the Most High. Perhaps he was sickened by fiery sacrifices of first-borns (even his own first-born son) to the moon-god.

But, remembering something, she turned to Assah. "I spoke sharply a moment ago, Assah, about the chieftain. I am forgetting myself. I miss those poor children in Keftiu so! Which is so odd of me! I never used to care for children! You know that very well!"

Assah gave Zenobia a concerned look and did not wish to discuss the past. "You're tired from the long voyage and anxious to see Hazor, my lady, after so many years in the land of red and black. And, as my mother used to say--"

Zenobia nodded, but Assah's kind remark and homespun village wisdom did not soothe her conscience entirely. She realized she had been on edge ever since leaving Keftiu. She and Assah had stood watching it burn, and the sight was branded into her memory.

It was not easy-going for women, as they adjusted to the forward rolling and sideways pitching of a camel's gait; yet it reminded them very strongly of the boat. Recalling that the voyage to Keftiu and thence to Tyre, Assah, in a playful impulse, lifted her white, linen veil. It filled and billowed in the strong, upwelling breeze like the lateen sail of the Ioteru. She might have laughed but suddenly she felt very sick and lost what she had of her last dinner over the side of her “desert ship.”

“What’s wrong?” Zenobia called to her. She would have called again but her insides too began to churn alarmingly.

Meshullam, who had foreseen that the women would soon grow belly-sick on a camel's back and weep and moan for him to stop the train, glanced at them a time or two. After that he never looked their way again until they reached the first camp just below the summit of Mount Lebanon.

Later, as they set up camp, Zenobia noticed Assah looking toward the aloof Meshullam; she thought about it a moment, then called Assah. She needed help with the tent as her Mizraimite retainers, all used to life in the lush delta of the Ioteru, were proving out of place amidst desert life. It made her think. When she was finished she called the homesick men to her the next morning. She gave them her decision and each a gift of an electrum ingot that would see them in good stead when they sought new livings in Tyre or wherever else they chose to live as freed men.

With Meshullam as witness, Zenobia wrote out their releases on papyrus. She asked for Meshullam to impress his signet on the documents. Only Ramoseh declared his intention to return to his master's house at once and gave up his own ingot and the freedom it meant, accepting only a few silver pieces instead from his mistress for his journey home.

“Joseph claimed me as his ward,” he said. “I am no good to anyone else, with this.”

He held up his stump of an arm, but smiled. “Now I am no longer tempted! It is a good thing after all! This way I never forget.”