S I X T Y - T W O ,

V O L U M E

I I I ,

U N C H R O N I C L E

I

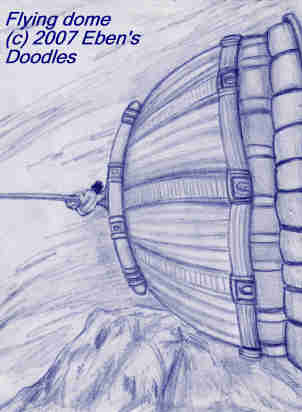

He had, in fact, toured Never- Never Land inhabited by the grandmotherly, kindly Mother Goose, only to encounter the most hideous vampires and attacking hordes of bats. A climb brings him to yet another unexpected experience. The magnificent all-copper dome of the train depot takes on a life of its own and affords him a second glimpse of something far worse than any vampire or bat.

Climbing to the top of the depot's all-copper dome, Ero saw an object lying by the base of the unused flag pole.

,p>

,p>

Gushing and overflowing with a red liquid, Ero had no idea what it was, except it reminded him of blood.

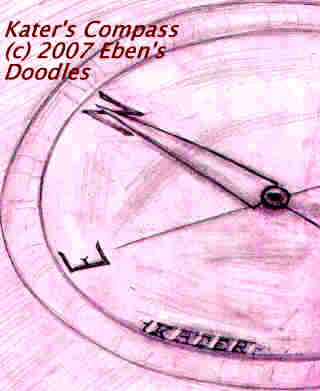

Ero, of course, did not argue, and complied immediately as advised, and the popup, no longer useful, vanished. As the flying dome rose under Ero's control, with the compass securely in Ero's hand and the needle pointing upwards as well, he saw there was another object hovering overhead--vast and batlike. It instantly flashed into his mind what it was there to do--it was a bat, and it was coming for a drink at that massive fountain beneath him--and the liquid continually pouring out of it had to be blood! Blood! What else would a bat want? This vast, dank, malodorous, water-floored palace was the haunt of a monster vampire, and here it was! He had no sword in hand, no cannon, the monster was just too big to fight with any weapon he could think of--what was he going to do?

"We are going to collide!" he thought, though the thought was not really a sensible one, as the flying dome shrank in comparison to the vast vampire, turning to the size of a tiny pinprick of sharp-pointed metal--a sort of tack that couldn't possibly slay so great a monster (as a mosquito could not kill an elephant).

As he struggled against the tusanami-like waves of hateful denial that swept down over him and mocked every atom of his being, Ero had no time to think about what was attacking him, for the flying dome converged with one of the flying cards. Instantly, the card sprang to life as Ero's mind was filled with the card's contents. It was Alex Hooper's whole life, played through Ero's mind in brief seconds.

He needed this job for the little money it paid--there wasn't going to be anything else for him in town but a blacksmith's helper position, or a stable boy's dirty drudgery, or some such low and stinking, manual labor. Here at least he could wear an ironed white shirt with cuffs and use his high school education, while hoping to save enough to matriculate at college someday.

He paused a little longer, still gazing wistfully out the window. How he hated Bloomington! It was sheer hell for a young man of his talents and ambition and brainpower. He didn't know anyone who cultivated the finer things of the mind like he did--he was absolutely alone as he went to the library shelves, reading one book after another, all the way down the racks of the philosophers, great poets and thinkers, and even the masterpieces of literature and art.

No, Bloomington's citizenry found "better" things to do than read and improve their minds! It was just like the stupid, ugly shoes that were stuck on the building's one entrance, on its door frames, on either side, which he had to pass between every time he went to work at the Courier. Imagine putting shoes, turned sole outwards with a hole in each one, on the upper doorpost to bring in customers to a combination barber-shoe repair shop! How it get more crude than that? That was old, money-grubbing Bloomington for you! Utterly shameless! Ever since the stoneware pottery and ironmonger's mill closed and the logging operations moved to the virgin forests of Minnesota, to make ends meet people did all sorts of humiliating, tawdry, tacky things! Though people tried to keep up appearances, it was all shame and pretence and shabby hypocrisy--Bloomington had no truly genteel, intellectually cultivated and informed people at all left in the city limits, nor any sense of refinement of the soul!

No one read good books to be found in the one library in town--they read only the Bible and books of devotion and prayer and such sniveling trash! It was all work and drudgery and meanness, six days a week! The seventh? Then they trooped, family by family, to church and submitted to the most tedious, brainless pontificating by a pompous ass of a parson to be found on earth.

He would be sure to pick a college as far from the town as he could get a train to take him! Perhaps he would even go out of state--to New York City! Imagine that! He would the the first in his family to do a thing like that--head east where people still knew what fine things were and lived truly cultivated lives. His parents would be mightily upset, of course, and worry that he would be corrupted by the big city and its worldly ways, when Blloomington was all they knew, and they thought it was the best of all possible worlds, being a town with one dominate church, his parents' United Methodist congregation, named, inevitably, Bloomington United Methodist Church.

But for Alex what a stuffy, old dump to have to grow up in--it was absolutely suffocating! He could predict everything that could possibly happen, except when a big fire might break out in an old warehouse or when somebody would run over a chicken on Main Street! He had made it out of boyhood, but he was determined to throw himself off the railway bridge into the river if he had to spend his manhood there just like his parents and all their dumb friends! What a fate worse than an early death! The very thought of being trapped in Bloomington the rest of his life made him feel like he was going to have another breathless, gasping attack, so he sprang up and dashed out for a breath of fresh air.

"Yeah, yeah, that's what I will do! I won't write what they expect me to write--that imbecilic, predictable stuff they seem to think has to be in the paper. Who cares what they want to make of the world or how they see it--they don't have a clew what the real world is like, and don't want to know. All they want to know is Bloomington! Well, I'll be my own man for a change, the master of my own destiny, the captain of my own ship, like Ralph Waldo Emerson says, and tell them the whole truth for once--the truth they're avoiding all their petty lives, and which they need to hear.

"Who else but me, Alex Hooper, will dare to tell them like it is?

"I will do it! I swear I will! That article quoting the whole sermon last Sunday--I will add brilliant Darwinian rebuttals to everything Rev. Smith said. And I have Olney's Ruins and Shelley's Defense of Atheism essay too to quote from. That will turn the whole stupid congregation of empty-headed fools upside down, as they realize what a backward, dogmatic buffoon they have been listening to all these years, presuming he is the golden-tongued oracle of God, when all he does is rehash the messages he pulls out of a volume of Spurgeon's Collected Sermons.

"Then the mayor's speech--I will point out all the flaws and deceit in his reasoning and explain what is really going on with his proposed budget, how he will stand to gain, enrich himself, by the road improvements and the alteration to the railway bridge and the other projects that tax payers are having to fund with increased taxes--which they all think are necessary (thanks to my editor's lying editorials), but which they don't really need, as the only purpose for these projects is to line the mayor's pockets! That's the unvarnished truth--which my editor is too much of a money-grubbing coward, too much in the pay of the all-powerful mayor, to tell the public! And I will rewrite the editorial and throw out all that stuff about the need to incalcate more virtue into the education of youth. Instead I will blow the whistle on our do-nothing, fat, lazy City Council, which has just agreed to hand itself a bonus and salary increase without making any prior public announcement of it. I will also quote some really good authors, like Shelley, Hume, Olney, Twain, T. H. Huxley, Thomas Paine and Voltaire...boy, why didn't I get going on these great ideas before? All I did was suffer like a dumb beast, just for this lousy pay I get--when I could be doing my part to change the world for the better!"

Alex made most everyone important in town mad. Even though Rev. Wickstrom was of the liberal persuasion and did not like emotionalism and camp meetings and such, he still believed in a Supreme Being. Therefore he was incensed, he was not at all amused, particularly when Dr. Pangloss's philosophy and even his person in Voltaire's infidel book, Candide, was applied to him. The mayor? He put the editor on notice that if he couldn't control the wild ravings of his own "printer's devil," that he would consider pulling some "contracts" and "ads" in the future he had planned to throw the Courier's way. As for the charges? Absurd! He wouldn't answer and had no need to demean and lower himself by answering to a mere boy who thought too much of himself just because he read books and could quote them.

So Alex was reprimanded, and put on probation, his articles carefully scrutinized by the editor and anything remotely creative or politically slighting to the status quo and its administrators in the world of Bloomington inked out with red and the offending articles sent back. That caused Alex a lot of extra labor, and no pay for it either--since it was correction of his own "mistakes" and the editor refused to pay for Alex's "mistakes."

But Alex had most trouble accounting to his parents. They gave him huge chunks of their minds. They had no idea he would take things he read in books and apply them to very important people in Bloomington or say such cutting, mean things about how the city's affairs were being run! They demanded he quit reading such dangerous books--they were ruining his life, and he might even lose his job at the paper. Then what? What would happen to his prospects? He could look forward to being editor someday, or at least assistant editor, when Mr. Oldham was feeling a need to lessen his workload.

"What prospects?" Alex fumed, when he sat afterwards in his room, his ears still burning with his parents' rebukes. He glanced at his desk's book case crammed with library books on loan--most all over-due. He had to return them now, as his father would force him, and then what? He needed them if he was to continue to learn what was going on in the outside world--it was his only real education, he believed. It was the only way he could expand his mind, to keep his brain from being shrunk to the size of a walnut like the brains of everyone around him had already been shrunk!

Being on probation at his job also was worse than death, in his opinion. He no longer had any freedom to write. It was worse than ever, to have every word gone over by the editor's magnifying glass, which he used to better spot some inkling of deviancy in his thought or meaning.

Worse, he had no freedom to think, if his books were returned to the library (where they sat unread on the shelves and gathered dust!). As much as possible, he escaped from the house and the work at the Courier and went on long walks. He had to think of something, somehow he could break out of the strait-jacket of Bloomington. He had tried to make them think differently in the town, and it had all backfired on him. He had guessed it would, but he couldn't help himself. They deserved everything he said. He had exposed the whole gamut of hypocrisy, small-mindedness, and conventional low life the town was accustomed to substitute for real life--and he was hated for it! They had muzzled him, gagged him immediately--without any discussion of the many valid points he had made! It made him furious to think about it, but he had to think of a way out. It didn't help to get mad, he realized. He had to take action and do something to better himself, despite the setback.

It all came to this: what action? What was he going to do? He didn't have the money to bolt! Not by a long shot! It took a couple hundred to make the move and get himself into college--and he hadn't but $75. That wouldn't be enough. He would be able to get there, but where was his tuition for the year? They wouldn't let him in the door!

He took out his application papers. He could forget about recommendations. He had offended the very people he had thought to ask, and now they would write something that would not help him in the least. One bad mention, and the college or university board would pass him over. There were just too many applicants for them to take a risk on anybody--unless his parents were well-known and could vouch for his performance.

Ero watched the whole development of Alex's growing frustration. Then he saw Alex suddenly check the train's timetable, throw some clothes and books in a cheap carpet bag with a flower pattern covering it, and sneak out of the house the back way--then run to the depot, arriving just as the train was loading for Chicago.

He paused, and thought fast. Either give up the idea of leaving by train, or go First Class, spending money he could ill afford to spend. He knew Dr. Wickstrom, a deacon of the church, was such a notorious tightwad he would never travel First Class--so he could avoid them altogether and the probing questions they were bound to ask.

He had no desire of long, bumpy wagon rides, hitched, all the way to Chicago--besides, he was dressed up, and it would ruin his $15 suit. He might even get robbed, tied up, and dumped by the wayside on some lonely stretch where there was nothing but fence posts and fields!

Paying for his First Class fare, he could hardly swallow as he realized he had spent a quarter of his savings. As he hurried to a First Class cabin, he felt better, though, knowing that he could hobnob with the well-to-do for the next couple hours and forget, at least try to forget, the loss of the money amidst the splendor he had only known as a boy peeking in the windows when a train stopped until the station master chased him away.

A bowing man in a porter's uniform was waiting, setting out a special red carpet-covered step for him, extending a white gloved hand to him to help him board.

"Welcome aboard, sir!" the porter said. "Have a good journey! Diner to your left, and the Gentlemen's Smoker to your right, followed by the Pullman Sleeper for your retirement in the evening."

Stepping right right out of his life as a Bloomington Courier drudge and smalltown boy and into the role of a wealthy young man of quality and genteel upbringing about to make his mark in the world, Alex nodded slightly to the fellow and boarded the First Class car, after handing the porter his carpet bag to put in the baggage car and a whole nickel tip.

It was a tremendous relief once he was inside, the problem of the Wickstroms' prying into his itinerary and plans eliminated. They would have spoiled everything for him!

He had an overdue library book of Tennyson's "In Memoriam" in his vest pocket to read, the poem that Queen Victoria had liked so much she made him England's poet laureate, and his fashionable walking cane for long walks in the park or "constitutionals"--standard equipment for Young Gentlemen in his copy of Miss Goodall's Book of Deportment for Young Gentlemen of Fine Breeding," and that was all he carried with him. Having peered in as a boy whenever the First Class cabins were at the depot, Alex had a good idea what they contained, but it was vastly different, he found, being inside one. It was like another world entirely--it felt, smelled, and communicated to him in a way that the dull, dusty workaday world of Bloomington had never done to him. He felt he had somehow launched upwards, in a few steps up from the station platform, and entered a wonderful new world full of exciting possibilities.

He found few people in the cabin, but he thought more would come in a few minutes, perhaps from the adjacent dining car and Gentleman's Smoker, as it was nearing time for dinner.

He was not there long in a seat by the window, fingering his slim volume of Tennyson's poetry, when a big-hatted, youngish lady in fashionable clothes sailed by, paused, then came and sat right by him.

"Where are we stopped now?" she said, with a slightly pettish, spoiled, irritated tone.

The town's name was in plain sight, painted on the depot wall in large brown, white-edged letters, but she was perhaps myopic, so he replied, "Bloomington," in a tone that he meant to convey he, being a rich young man with brilliant prospects, had only the most casual acquaintance with such a hick town.

"Oh, really?" she replied indifferently, but turning to him with a warm, sweet smile that absolutely enchanted Alex, along with the perfume that wafted over him from her silk skirts.

"Yes--that's the name of this wretched, little farm town," he said, faltering, as he was so captivated by her already. "You wouldn't like it. It's really nothing--nothing to speak of--a bump on the road to better places--"

"I do wish they wouldn't stop in such out of the way places then!" she added. "It is a nuisance making all these dreary stops in the country. I had hoped for a more direct train than this one--but I wanted to be back as soon as possible. I have a nice litle party planned, you see, and there's all sort of preparations I--"

She paused, her eye on his little book.

"What are you reading, do you mind telling me?," she asked, abruptly changing tack as her arm pressed against his.

Alex showed her his book. "--I also like Byron and Shelley and Wordsworth and other English Romantic Period poetry very much--though, like Lord Alfred Tennyson, it is on the sad side generally."

"Melancholy--you mean? Melancholia is so much finer a state of mind and heart than mere sadness, don't you agree? Oh, I love being melancholy, sunk in a brown study, they used to say! Modern life is entirely too, too frivolous--at least the people I know. I much prefer the more serious minds and hearts, people who know life at its deepest and most tender--but they are so extremely rare in Chicago. It is such a harsh and cruel and smelly place for sensitive people like us--I hated it immediately when we moved here from Milwaukee four years ago, when Daddy sold his invention to Mr. Cyrus McCormick, something to do with perfecting Mr. McCormick's reaper, and bought that big house above the lake--"

She paused, took a dainty gold-flowered silk fan out of her purse, fanned herself most elegantly, then smiled in the demure girlish way that had first captured his heart.

Encouraged by her manner, Alex ventured a remark of his own. "How are you able to live in such a crass city then--I mean, do you read a lot to pass the time?"

She seemed to leap at his question, pressing against him all the more. "Oh, but I am telling all about myself, and you? You haven't said one word about yourself, and I haven't let you. I've just been rattling on about myself!"

Even as she said this, the cabin gave a lurch, throwing them apart, and the train was moving off, leaving, he hoped, boring old Bloomington and all the things he despised, forever behind him.

Just then Alex remembered what he should have done before the conversation went this far. He sprang up, dropping his poetry book, and bowed and extended his hand. "Alex Hooper at your service, Madam!"

She was surprised at this display of bookish old world manners and stiff, awkward execution, but laughed, then extended her kid-gloved hand. "Dorothea Worth Dalt--but you can just call me Dorrie--as I hate Dorothea!"

Alex sat back down, and the conversation sped on, and time was forgotten. Suddenly it was all over, as "Dorrie" arose, explaining she had to get to the diner, as her husband Mr. Dalt would be wondering what had happened to her. He could get angry, she added, if his dinner was held up.

But still she turned back, handing him a gilt-lettered card from her purse. "Do come and visit me soon! We simply must finish this delightful conversation about your adorable Tennyson and the other wonderful poets I'm sure you are reading. Ivanhoe was marvelous--I read several chapters once of that book. And I do love the poets and writers of England, Scotland and France! They have so much sensitivity, something which the modern world knows nothing about, especially in Chicago! All Chicago cares about is making heaps and heaps of money! Ugh! But you seem different somehow. So do please call on us, preferably in the afternoon when I receive calls in the drawing room. If you call in time, I'll invite you to my party this coming Friday after next. You will meet some nice, sensitive people there--it's difficult to do, but I try to invite that sort to my parties if I can find any in the city."

A smile, a final handshake, and the most exciting person Alex had ever met hurried away in her crackling, silken, perfumed skirts. He didn't dare follow. He hadn't the money to spare for a full five-to-seven course meal. Then it would be followed by drinks and cigars, and even more expense with tips to the waiters and bartender. No, best stay in the cabin where he was, and read his poetry book the rest of the way, and try to control his rising fears of what he might be getting himself into when he landed at Chicago's main depot.

The cabin rolled to a halt, steam was pouring out around the cabins from the boilers up ahead, clinkers were raining down on the roof amidst the smoke from an outgoing train, and the porter was shouting up and down each cabin, "Chicago! Chicago! Detrain here, ladies and gen'lmen, for all points east-- New Yawk, Philly, Newok, Bawstin! Collect all baggage!"

There was a rush to disembark, and with his ears ringing with "Chicago! Chicago! Detrain here!" Alex found himself being hustled off the train amidst a stream of passengers. No one paid any attention to him now--it was every one for himself in this great, devouring metropolis that cared only for money and power, spitting out anything less.

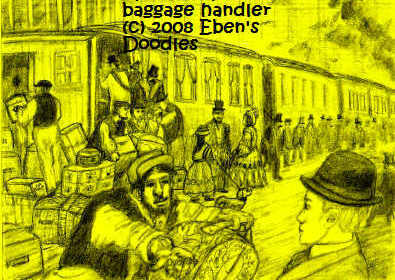

"Oh, where is my bag put?" Alex suddenly thought, alarmed he might lose it in the swirling, deafening madness and confusion. But as he stepped down from the train car, he saw the baggage car was just a few cars down from his, and already it was being unloaded for the impatient passengers. The local union of baggage handlers, however, roughly shouldered aside the train's personnel and did not allow anyone but themselves to transfer baggage from the train to the platform, and then they expected big tips as they handed it to the people who came to claim it.

This wasn't the way things were done at Bloomington, Alex knew. No local union had that much control over the big railways and the baggage! This was sheer robbery! He could get his own bag, thank you! And without paying anybody!

He spied his carpet bag as he peered over the baggage handlers' heads, and tried to reach in, but a baggage handler turned and gave him a push back. "Nossir! Dat's our job! Let me git it fur ya! Which one is yourn?"

Alex made another move to reach past him again, but the baggage handler was even more rough with him, giving him double the push. This made Alex mad, but what was he to do? The baggage handler was the bigger man in size, if not height, and he had his fellow baggage men to back him up too.

He had no choice, so he pointed to his bag, and the fellow grabbed it and then shoved it at Alex. "Okay, you can take it now, sir!"

Alex put his hand out to take it, but the baggage handler yanked it away, sticking out his hand for a tip. "Ya furgit somethin'!"

Furious, Alex sacrificed another precious nickel, which would have bought him a solid lunch of eggs, bacon, pancakes, fried potatoes, and coffee--a sum he knew was more than the usual tip could possibly be for this unwanted "service"--and the fellow smiled this time, showing his chewing tobacco stained teeth, and shoved the bag so hard at Alex he was thrown back, sprawling on the dirty boards of the platform, while everyone stared at him with surprise.

"Boy, you done skirred that snotty little rube real bad!" one crowed to the others, and they all laughed the harder.

It took quite a lot of walking in the labyrinth of over-crowded neighborhoods and districts that fanned out without any order or civic planning before he began to look around and tried to forget the ugly bullying scene back at the depot.

As a high wind gusted right into his face and made it difficult to walk against it, for the first time he realized he had bitten off more than he could chew in coming to Chicago, as this was a metropolis, not a humdrum, sheltered little town like Bloomington. A thousand Bloomingtons could fit inside Chicago, and still be swallowed up!

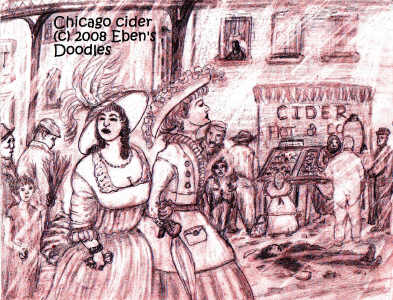

With all styles of hats, hairdoes, and clothes looking so strange and odd to his eyes, people from all the world and representing many races thronged Chicago's vast thoroughfares, streets, and emporiums.

Alex paused to refresh himself at a cider stand, resting his feet a bit while the crowds moved past around him.

The tin cup emptied, he returned it to the lady vender, then saw her fill it from the huge crock of cider, and hand it to another customer. So they didn't wash their utensils! n He should have known! But it was too late now. If he got sick, it was his own fault!

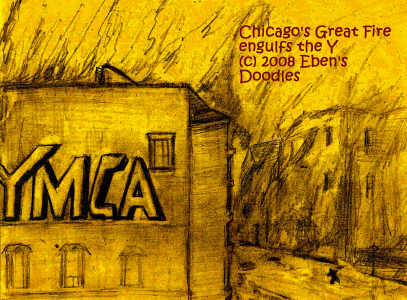

Off he plunged into the traffic and continued from street to street. After a while, feeling footsore, dodging muddy water and horse manure splashed from the wheels of thousands of passing wagons and carriages, trying to keep out of the way of loggers, stockyard men, and other rough types that crowded together down the sidewalks, shouldering even ladies and elderly people aside from their path, Alex stumbled across the Y.M.C.A. on Madison Street.

Ero watched it happen this way. As some of the biggest stockyard brutes Alex had seen, cattle blood all over their clothes, started his way and he saw he was going to be pushed into a huge mud wallow that ran alongside the sidewalk, he didn't hesitate. He took an extreme right turn through the nearest doors of a big, newly opened building. There he stood, confused and surprised at first. Strangely quiet in the large lobby, it was like an oasis of calm and cleanliness in the midst of a big, dirty, smelly, brawling circus of a city. Looking about, he was relieved when he realized where he had landed. It was just what he needed! He hadn't thought of it, but the Young Men's Christian Association had, he knew from its well-known reputation, just the right prices for any young man seeking a clean, safe place without boarding with a lot of bedbugs and thieves. Here he could hang his hat and set his prized gentleman's walking stick for a while. As for it being Christian, he decided he could manage to live with that, since he wasn't going to be there very long and wouldn't be compromised in his atheist beliefs, he reasoned, with such a short stay as he planned was necessary.

A few minutes later, he was at the front of the line waiting to cleck in, and the desk clerk in a Y.M.C.A. emblazoned shirt introduced himself as Will Withy and politely asked him what the Young Men's Christian Association might do to serve him.

This was simple enough, Alex thought, but Will Withy peered at him more keenly than Alex would have liked, and did not seem too impressed. On the contrary, concern showed in his face.

"But have you got your parents' permission? What did they say about your coming here? I can't believe they'd let someone as young as you come out here on your own to fend for yourself. Despite all the big businesses, this is not an easy place for finding work. Chicago can be a brute of a place to make a go in--despite the big money some folks make here. For every rich man there's thousands of able bodied men out of work, and most of them are day laborers, without any fixed jobs. They don't really want steady work, as they are always quitting to drink up their day's wages, whether they have wives or children to support or not. And besides these rough and untrustworthy fellows, there are all sorts of wicked people, wolves who would want to take advantage of you any way they can. Can you spot them and stay clear of them? And what work exactly are you wanting to try? What is your experience and training?"

Not expecting to be quizzed about such things, Alex was not prepared, and he was annoyed. Speaking a little defensively because he knew there was little comparison with Chicago and Bloomington, he declared, "I've been employed in journalism, and maybe that will be my profession, if I like your Chicago paper well enough." The Y.M.C.A. man looked at him with amazement. "We have more than one, don't you know? Which one? "The Sun-Tribune? The Morning Telegraph? The Times? The Patch Dispatch? They haven't notified me here that they are hiring at the moment, but perhaps in a few days. You can check them yourself, but we would be the first to know here, as they have an agreement with Mr. Farwell, who by the way paid for this fine building we have, to let us know first before they make it public in print."

Alex gave the only Chicago paper he had read back in Bloomington--the Chicago Sun-Tribune, which came in old issues used for packing the printers ink and paper they used at the Courier. Will Withy checked his list of jobs, and then shook his head. "Sorry, none of the papers are hiring at present. You'll have to wait. But maybe you have a second profession in mind. That would be a good idea to try while you wait for a job on the paper. Otherwise you might be waiting forever! Everyone wants to work for the big papers--they're mostly all union shop, the work is indoors during the winter, and the wages are good compared to the stockyard jobs, which is where most immigrants and newcomers to the city end up, like it or not."

When the inquisitive Will Withy was through extracting, Alex had reluctantly given out all his wretched particulars and lack of prospects, as the clerk knew just what to ask and keep prodding until he got the whole story.

As the line was growing long behind Alex, he smiled and said, "You'll have to go and ask around the big dry goods stores for stock boy jobs or maybe errand boy or even janitor jobs in the company offices or the city government buildings--that's about all you'll get now, since there is so much competition, and they're all trained and experienced too. It's sounds unkind to have to tell you this, Alex, but you'd be wise to return to Bloomington on the next train you can catch. Don't stay here, Chico will eat you alive! It's a very mean, hard-hearted, dangerous place, outside these walls--here you are safe and we will look after your welfare, but you have to go out sometime, and then you are on your own. Only God can help you in this jungle of the big city! I'll have to tell you my own story sometime, how I as rescued right off the street, and would be dead by now, if--but, oh, by the way, we have a prayer and Bible study meeting three times a week for the young men in Room 212, the main hall on the second floor, at 7:30 p.m. Be there! Our president will be on hand to speak at the meetings, he's just returned from a long trip abroad. You'll get the encouragement you'll need if you decide to stay on, despite my best advice!"

Will Withy smiled at Alex's show of manly determination, said he would trust him for the room's payment and he could pay when he signed out, then handed him the key and wrote his name down and the date he would be signing out. Along with a cake of soap and toothpaste and comb in a small kit, there was a pocket New Testament and a tract, which the clerk pointed out to Alex, and, lastly, a printed map of the area so Alex could find the newspaper headquarters he was seeking.

"I'd add shaving soap, but I see you probably don't shave yet, right? Don't forget, you're invited to the prayer and Bible study meeting! I'll be there. In fact, everybody will be--we usually have two to four hundred hundred boys, everybody that's staying here, as well as thirty or forty boys off the street that Mr. Moody picks up along the way here. Mr. Moody is having the meeting, you see, and wouldn't miss it! He loves telling us about Jesus and the Word of God. You wouldn't want to miss Mr. D. L. Moody--he's like nobody you have ever heard! Talks so fast you really have to listen hard to get all his words."

Alex frowned, grabbed his carpet bag and headed up the wide stairs to his room. Prayer and Bible study meeting? he thought. He wouldn't be caught dead in one! Imagine, praying and reading the Bible! He had came to Chicago to try his luck! Old Bloomington had no future for him--the future for young men such as himself was in a big city, like Chicago or New York. And as for Moody, who was he? Wasn't he the "foolish young preacher" his pastor said was a revivalist you couldn't trust, as he hadn't any education and hadn't ever gone to seminary?

What was most suitable for the ears of a high society woman, as this lady appeared to be? How old she was, he had no idea--older than himself, he thought, but not much older, surely. She talked so like a girl, she couldn't possibly be thirty. She must be in her early twenties. And what would impress her, coming from what he appeared to be, but was not? He had to keep up a certain air of being accustomed to affluence but possessing up and coming prospects that would suit his youth--so what was his profession or his reason for coming to Chicago going to be? He had to think of many things he could answer her should she ask.

Gasping with surprise, he wondered what had happened. He carefully approached the rapidly dying fire line, and then found it had burned itself out along a recently cleared strip of ground someone had plowed up for a garden. That had saved him, for the dead, tinder-dry grass and brush was just as thick on the side where he had been standing, only the sparks had not reached it, shooting upwards instead into the uprising winds.

Vastly relieved, he gave a sniff to his suit collar, and it wasn't affected as he had feared, so he could call on the Dalts without having to go back first and change (though he had nothing as good to change into as this suit).

He continued his climb and soon came to a new street, which had a guard post and gate controlling the hillside leading down toward the city limits. He showed the Dalts' card to the Pinkerton he found on duty, then followed the guard's directions which took him straight to the mansion which was set at the end of a long winding street, with other lots around it not yet occupied. The wind was blowing hard, so rather than chase his hat, he took it off and continued the rest of the way, hat in hand.

"Please inform Mr. and Mrs. Dalt that I am calling," Alex said, removing his hat and keeping his voice as casual and cultivated as possible, as if he went calling at grand houses frequently.

The butler glanced from the card to Alex, seemed doubtful, then asked Alex to wait, and left him at the door, which stood ajar. Alex heard a piano lid crash, then a door being shut just as hard, and rapid heel sounds, receding away from him.

The butler returned, and there was a slight difference in his manner, a certain rigidity by which Alex could detect something not too promising, and his heart sank.

"I'm sorry, sir, Mr. and Mrs. Dalt are not in. They are out of town. Call another time, perhaps in a few weeks, if you like. They might be back from New York then, unless they take a trip abroad, and then it will be another six months."

Alex stood stunned. He could not believe the butler's words. He reached for Mrs. Dalt's card, and brought it out. The butler glanced at it, but shrugged, and handing over Alex's card to him, slowly shutting the door in Alex's red, flushed face.

Was it his card, which lacked an impressive gilt edge, a giveaway perhaps to a society person that he was a sheer nothing, a poor boy trying to escape from a small town in the country and eke his way into quality society? He had tried hard to put on a convincing impression, but they had seen through it? What had he done wrong? Miss Goodall's book had failed him! She was an old fraud!

Finally, he stumbled away, for he couldn't stand there like that looking like an utter fool. Someone might hail a patrolling Pinkerton dick and have him taken away. It wasn't proper behavior to loiter among the homes of the rich, they were trespassers, and only people who came in wagons and carts and serviced them with ice, dairy products, coal for their furnaces and stoves, firewood, and purchases delivered from stores and shops, or took their laundry for washing were permitted to come and go freely--so he was not in any way entitled to be there, not after being refused at the Dalts.

The wind was blowing hard in his face, forcing him to hold his hat in his hand, and so he decided to take another route back, without taking the road. He was walking slowly from the grounds and had rounded the walled yard running from the back of the mansion when he heard someone call his name. "Alex! Mr. Hooper!"

He could not hear it well, as the voice was muffled and seemed to come from behind the tall and thick yews on the other side of the wall. Crossing over the lawn, he approached the garden wall and then saw there was a gate, and a lady's gloved hand was beckoning to him.

"I can't let you go like that! I'm so glad you walked back this way instead of by the road, so I could catch you without being watched! How low and rude and uncultured of us! My husband is a brute, a tactless beast, he is so insanely jealous of me and my friends! But he can't stop my parties and my inviting whomever I wish--as my money came with me in this marriage, and according to the terms my Daddy drew up, I am my own woman, married or not, with or without stuffy old Theodore, who is twenty years older and doesn't understand young people in the least! So you shall come to my party next Friday--if you would like! Be here at 4 sharp, and I'll leave word for you to be let in--no matter what. If my husband is here, you'll be directed round to the back entrance and I'll make sure Theo finds out too late to stop your joining us--so you're coming, whether Theo likes it or not! He wouldn't dare cause a scene in front of everybody! And my personal friends are my own business--not his! He never invites me to his men's club meetings! So come, won't you, Alex? We have so much in common, with books and poetry and such, don't you think? There aren't ten people in Chicago who read the books you do--there's so much barbarism here. You might even want to recite your favorite poem when we stage our tableaux. Please don't think of disappointing me!"

Still giving him no chance to do anything but nod, she smiled in her sweet, enchanting way, then closed the garden gate and vanished into the shrubbery.

Alex's heart, which had nearly died in his breast a few minutes before, now sang like a lark as he made his way all the distance back down from the heights of the wealthy and down through the warren of traffic-clogged and muddy streets of the mass of Chicagoans to the Y.M.C.A.

"Hey, boy, how do you know the Dalts? I've been trying for over a year just to speak to the gentleman about a certain matter important to me, and he can't seem to find one minute for an interview. Can you get a word in for me? I really need to see him about somethin'. You've got a job here under me, if you can do that!"

Alex's sagging shoulders straightened all of a sudden, and ready to promise anything, he nodded, and Thigpen snatched a yellowing paper slip from a nail on the wall.

"Here then, we got nobody to do this particular bash job, so you do it! The guy its about has been outa town quite some time, I hear, preaching up a storm over in England to hunnerds of high class suckers they have over there, but he's supposed to be back in town any day now. You're a reporter now for the paper! You report first and last to me, git it? Now you go and rake up the stinking dirt on him--give us the details of the racket he is running down there at the Y.M.C.A., using those street kids of his he scoops up out of the gutters in order to milk this town's bleeding hearts and rich folks for contributions to his so-called 'Sunday School.' Sunday school, my arse! Mr. Farwell is one of 'em, he's solid in Moody's bag, puts out tons of cash for Moody's projects. We know this Moody's pullin' in thousands more with this bogus ministry of his, and it's gotta be goin' right in his pockets. He's no different from inybody else in this dog eat dog town! So rustle up some little proof of it--just enough so as to make the town wonder if they haven't been hornswoggled. We don't have to see it taken to court. Naw, not that much proof! Just one little article in our paper should be enough to shut up this big-mouthed preacher and send him packin' to another town where they don't know him quite so well. Be sure you don't quote anybody or name anybody big here that would land us a libel suit, or you be dead--I'll take care of you myself!

So you're on probation, and don't get paid until I see it is worth printin'! You can maybe use the desks in the clerical department, if somebody will let you, and later, if you prove yourself, you can have your own desk. Well, do you want the position? Of course you do! Now to the more important matter. You've got to promise me you will ask Mr. Dalt for me, the next time you see him, whether I can see him about being my sponsor at the Red Indian Brotherhood. At least get him to listen to me a minute, and I know how to sweeten the whole thing for him. Can you get that interview for me? This is the only opening I've got for you--so if you can't handle it, there's plenty of other--"

"Oh, I can handle it, sir!" Alex said, extending his hand to Thigpen, who looked at it disgustedly. "Oh, cram it! I don't even know who you are! I wouldn't wipe my arse on the likes of you. You aren't anything here yet, and I only shake hands with my betters. As for you--you're just dirt, even if you do know the Dalts somehow. Do a good job, get me what I asked, then maybe I will be ready to shake your lily white hand. Now beat it! I don't like looking at pink-cheeked, beardless choir boys tryin' to act like real men!"

He was exclaiming over and over to himself, "I got a job! A job!", not noticing that the other applicants, fellows just as needy as himself, were staring at him with envy and then anger, when someone said he had pushed in ahead of them.

But he soon sobered enough to think. What kind of job was it really? Would it pay enough to be worth the work he would have to put into it? What was this article anyway he had to write? And could he get Mr. Dalt to agree to seeing the likes of this dingy Rasmus Thigpen, someone who looked like he belonged more in the stockyards knocking cows in the head with a mallet than he did in a respectable newspaper's precincts?

Alex's blood chilled at the thought of Mr. Dalt feeling deeply insulted by the request and refusing. He knew Mr. Dalt was perfectly justified in refusing the company of such a creature as Thigpen. What then? He would be thrown out of his new job if he didn't produce, even if he did write an excellent article on the man Thigpen had described to him. After all, Mr. Thigpen was dead set on getting accepted at Mr. Dalt's Red Indian club.

He paused to read the scrap of paper on which Thigpen's assistant had jotted his assignment. There was just a man's name--D.L. Moody. Alex's eyes widened as he remembered it. Hadn't Will Withy invited him to go to this man's prayer meeting and Bible study? It was one of the days the Moody fellow would be present to speak. He checked his silver-plated, Roebuck Company timepiece, a $10 gift from his father and mother for his graduation which he carried in his coat's inner pocket for safekeeping, since it was the most valuable accessory to a gentleman's portfolio he possessed, other than his knowledge of fine literature and poetry. He had just enough time to go to his room, take a good hot tub bath, dress, then make it to the meeting with his pencil and notepad, if he hurried.

This got Alex's attention. He waited, unable to decide whether she was crazy or really had something worthwhile to hear.

"Young man, I saw just now a fierce and terrible fire burning, a very great conflagration in a big city like this one. Could Chicago be meant? And you were running, running straight into it! I don't know what that means. Could it be the fires of youthful temptation, in which so many young souls in this wicked city perish even as we speak? Perhaps the Lord will inform me, so I will pray for discernment. If He reveals to me the meaning, I will be sure to let you know. Will you be staying here for the next few days? If so, I can reach you here, as I often come to pray for Mr. Moody's meetings, but I have to be going now--my sister is ill with an attack of consumption, and my mother is aged and needing care, as my sister cannot help her, to free me up for prayer here. Please excuse me! I forgot, people call me Auntie Sarah. And your name, young man?"

"Alex Hooper."

She gave him her hand ever so lightly, moving her lips as she did so in what might have been a silent prayer, then turned and moved swiftly away to the stairs, and went down, leaving Alex wondering what on earth to make of her "impression," or whatever it was.

Poor and homeless, raggedy boys from the street and YMCA residents hurried past him, and he remembered what he needed to do, so he went in, arriving late, as hundreds of young men were already seated.

Seated on the aisle, he could see the speaker directly ahead however, already casually standing and giving his talk from the side of podium, not behind it.

Alex also observed that Moody was a broad, thickset, not overly tall man, dressed in a decent russet brown suit of no particular, fashionable cut, with lots of wind-blown bushy beard, moustasches, and curly hair fallen in locks across his high forehead. Someone said he had hit town as a youth and quickly become the city's premier shoe salesman, banking a windfall of thousands due to his phenomenal sales pitch, proving he could easily become one of Chicago's business giants in a short while, but embarking instead on preaching the Bible as his stated new calling in life! Was he crazy? Who would give up a real, sure chance of becoming a millionaire for preaching the Bible and teaching at paltry Sunday Schools?

Was this the great man, the international speaker, that had just returned from prestigious engagements in London and all over Britain? The more Alex scrutinized the man at the front, the less he was impressed. He decided that Moody could not have changed much from his shoe-selling younger days--he was just older and stockier. Distinguished with the passing of some years--not at all! He still looked to Alex like a tradesman or shopkeeper, of a middling sort of business, like a dry goods or general store. But this was the mystery of the man! Appearing so common and ordinary (making so many mistakes in grammar as he spoke), how then could sophisticated, rich people in London and New York be attracted to such an uneducated, unrefined man, when they could afford the best of America and Europe had to offer? What was his special angle? Mr. Thigpen had sent him to find that out, had he not?

The moment "Onward, Christian Soldiers" and other rousing choruses of the songfest ended, men and boys poured into the aisle and most all tried to reach Mr. Moody, but there was no getting close to him, he was so completely mobbed by those fortunate enough to be positioned near the front.

Giving up the idea of a personal interview, Alex had to content himself with his back-row impressions, while he kicked himself mentally for not bringing along more pencils. The notes he had taken might help some, but he would have to rely on his memory to flesh out the message. What was he saying toward the last--something about "there's no limit to God's love for you, young man--you'll never find anything like it, or better, in this dog-eat-dog, squirrel cage and treadmill world!"

"My, didn't he mix metaphors!" Alex thoughts sourly.

Rather than try to push through the laughing, joking, jostling, good-humored crowd to get closer to Moody, Alex moved the opposite direction and waited in the hallway. It took some minutes for Moody to make his way from the front to the rear, and in that time Alex noticed a group of dirty little street urchins--the snot-nosed sort he had heard Moody patronized and tried to do something with by recruiting them for his gigantic, thousand strong Sunday School.

Were they all without proper fathers? Alex wondered. And where were their mothers and grandmothers? How did they come to find themselves living on the streets, without anyone to look after them? It had to be their own fault--they were lawless, bad, good for nothing little boys, Alex concluded.

One even carried a broom, right into the building, he was so uncivilized, Alex observed. Probably had come straight from sweeping out a saloon for a beer and a horse meat sausage sandwich! Such ignorant little barbarians as these probably did not think they didn't belong in civilized society! he thought. Yet no one stopped him or took the kid's dirty broom away.

Suddenly, Mr. Moody was standing right in front of Alex! Alex was so surprised, the questions he had made up to ask him flew right out of his mind. He tried to think, but nothing came to mind. But he thought of something else, how his Rev. Wickstrom had questioned Moody's theology, commenting that Moody's notion of unlimited grace logically eliminated the need for good works--and without good works no religion could possibly be any good in the world--it was a worthless "esotericim," a "gaudy trifle not fit to engage modern society," to use Rev. Wickstrom's phrases. Remembering this, Alex knew he had something he could probably work into an article that would refute everything Mr. Moody had preached and stood for.

"Oh, Mr. Moody--"

Moody turned his head, glancing at him with those exceptionally warm, kindly eyes of his.

"Yes?" he said. Already the street boys were on to Mr. Moody, grabbing his hands and arms, but still he was waiting, Alex saw, for his response.

"I would like to ask you a few questions for the Sun-Tribune, sir, if I might, concerning your, ah, theology."

Moody peered closer at him, then shook his head. "Theology, young man? Your paper is interested in my theology? I have no theology!"

That said, Mr. Moody smiled at Alex and strode off, a dozen or so boys hanging on his thick, meaty arms and shoulders.

Alex gazed after him, his mouth dropping open, considerably at a loss. He took a few steps as if to call after Mr. Moody, but stopped. There wouldn't be any chance now of regaining his attention, he realized. He had asked the wrong question!

The wind taken from his sails, he did not know how to react at first, and drifted with the crowd for a few minutes as the building emptied of the visitors. Finding himself outside the building, though he had no reason to go outdoors, he glanced up, saw a reddish and smokey cloud hanging over the nighttime city which the street gas lamps could not drown out, and thought nothing of it. But he thought again when more and more people in the street paused to stand and point up at the sky, remarking to passers-by about it. The traffic was beginning to clog up, due to the many carts, wagons, carriages, and policemen on horseback who had stopped in the middle of the street.

Then people, with alarm on their faces, started crying "Fire!" That started the stalled traffic moving again, in all directions, as everyone began moving as fast as they could toward their various neighborhoods and homes

--everyone but Alex, that is, who only had the Y.

It did not take long before Alex thought it was much ado about nothing. What was a little smoke and fire anyway? Alex did not see what the hubbub was all about--as Bloomington had fires every so often, but only a couple buildings burned down at a time, since the empty, grassy lots kept the fires from spreading very far. A warehouse or lumberyard might burn down--but Bloomington always got along without them and went on much the same as before.

Going up to his room, he decided to spend the rest of the evening on his article, writing it in longhand, as his first draft. After he had got it to perfection, he would take it to the paper's clerical section, where they had installed some of the new typewriting machines.

He worked with his lamp burning until he finished the draft, and then sank exhausted on his bed, without removing his clothes and fell asleep immediately.

A pounding on the door made him spring to his feet. What was happening? He stumbled over to the door, getting his feet caught in a rug. He opened the door, and it was Will Withy, his clothes all rumpled and his hair uncombed.

"Everybody out of the building immediately!" the desk manager shouted right in his face.

"Why?" said Alex, rubbing his sleepy eyes.

Will looked at him as if he were crazy. "But don't you know? There's a big fire burning straight this way. Hundreds of houses have already been destroyed, and it is on course to do the business district next, and that includes us! So grab your things and get out of here, or I'll make sure you leave!"

Will rushed off as he saw Alex was moving to get his clothes and belongings.

Alex looked around, wondering what he should take. Then he stopped, Where would he run? He had no other place than the Y. Unless he tried to get to the Dalts, there was no one else in the city he knew who might possibly take him in. What a spot to be in! But there was something else--the article. He couldn't leave it. He took the eight pages of the draft, tucked him into his shirt, and decided he would try to get to the Sun-Tribune. He ought to be safe there, he reasoned. It was a solid brick and stone-faced building, not like the Y, which was a big but wooden, stucco and plastered building that would be far more flammable.

Ero, looking on from his vantage point, was watching the entire city catch fire. It starting small enough, from a single kerosene lamp overturned by a bossy in a cow shed like so many others cluttering the junk-littered back lots of the wooden tenement and saloon district called The Patch. It was milking time come dusk. A fire broke out in the hay when the cow, in the process of being milked by the woman who owned her, got impatient after the woman was called away to the house for some reason, and a hoof suddenly flew and kicked over the lamp. That sort of thing happened fairly often, but the milker or employed barn help was always present, and the fire was doused, with a gunney sack soaked with milk, if no water was available. But this time the fire was not discovered in time. The cow's owner returned too late, and she found, to her horror, a bellowing milch cow enveloped in flames, kicking her stall to pieces as she lunged back and forth, crazed with fear. What could the owner do for the crazed beast? The lady fled back to the house to get help.

But there was no stopping this fire from spreading. Fanned by the strong gusting wind that regularly swept the city's streets and neighborhoods like a thousand giant brooms, the fire leaped from the cowshed to the neighboring fences and structures. In only a few minutes rabbbit hutches, outhouses, sheds, stables, and then houses ignited, driving the occupants screaming and shouting into the streets.

Even so, Chicago was a big city, big enough to absorb a lot of mayhem at any one time and still keep going as usual. And at dusk and nightfall people were settling in to enjoying dinner and making preparations for either gaiety in the various places of amusement or going off to bed, so it took some time before the rest of the city thought it was anything for them to drop whatever they were doing and take notice.

An hour later, with all the city's fireman brigades hailed out of their houses and beds to hurry half in and half out of uniform to their various fire halls where the fire bells were ringing up a storm, the wind blew more fierce than ever and made their best efforts fail to account. It did not matter that they were soon at the scene of the blaze with their fire wagons, pumping water from big wheeled tanker-wagons onto the fire as fast as they could.

Falling back before it, the fireman saw that the fire now threatened to incinerate the entire Patch --and after that, it was no guess, the entire city was imperilled. To save the business district, which bordered the Patch and lay between the Patch and the lake, they would have to do some drastic, unpopular things. The Mayor and Fire Marshal hurriedly conferred, and the decision soon came down from them to the anxiously waiting men milling around in the street below--blow up a row of houses all along the line of fire! Use all the dynamite it takes, but get the job done as soon as possible!

It was a terrible thing to have to do--as how could they alert everybody, or see that everybody was out of those damned houses? There were the usual deaf, elderly, shut-in folks, who wouldn't know what was going on. They wouldn't budge, even if they knew--they'd hold on for dear life to the only things that mattered to them, even if the fire was blazing a block away! What about them? But they could not stop doing what might save the city--and so the order went ahead, and the men who knew explosives hurried down to the Patch, struggling through the masses of humanity, wagons, and animals that were pouring out of the Patch via every available stretch of road, open space, and river bridge.

Ero watched the first houses blow up, and then an entire row dissolved with tremendous Woomph! followed by a terrible, big, slumping sound, as if an elephant had stumbled and fallen. They had no sooner collapsed and cleared the area, when the the wall of fire reached the leveled zone. The firewall died down almost immediately, and a cheer went up around the Mayor and Fire Marshal where they stood watching from the top of City Hall. They were shaking hands when Ero saw something they could not see. Some fire was still licking at the edges of the downed row of houses--the firemen with shovels, sand, and water, still had got it all out--and the devilish wind managed to snatch up some of that lingering fire and flung sparks across the intervening space.

It could not be helped. Another blaze erupted across the fire lane! Shouting to each other to "get their asses in gear," the firemen cursed everything they could think of as they rushed across to put it out before it spread, but they could not get there in time. The wind was seemingly determined to help the fire anyway it could, and whipped the flames up from a burning shed and the roofs of houses and sheds also caught. Again the people started to flee in the hundreds and thousands, though some remained behind to try to save homes and property with buckets of water drawn from their wells.

Could another row or two of houses be blown up and stop the thing? the Mayor shouted at the Fire Marshal. At a loss to know how to fight such a wind, the Fire Marshal did not seem to think it would matter much. He gave his assent, but shook his head, and then turned to the Mayor. "It's every man for himself," he said. "We're not going to stop this big a fire, not with that blacksmith's bellows of a wind behind it!"

Ero saw the dismal looks on the Mayor and his men when the Fire Marshal gave up fighting the fire as a lost cause. The city's skyline reddened even as he spoke his fateful words.

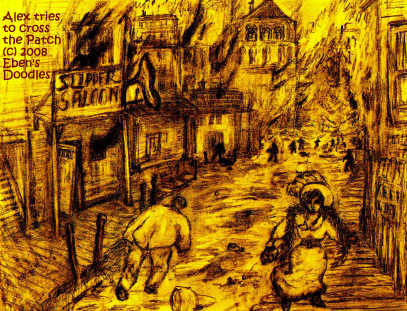

Minutes after this, Alex was well on his way toward the offices of the Sun-Tribune. On impulse, he decided to cut across a narrow stretch of the Patch that cut through the business district as it followed the river. This was the very worst, seediest part of the Patch in reputation, containing mostly rotgut saloons, bawdy houses with floozies full of the clap, dance halls where the clients got shaken down after groping their partners for five cents, Chinese opium and gaming dens, cock fighting arenas, counterfeiters, illegal stills, assassins for hire, escapees from prison, a handful of fake counts and princes, has-been actors and actresses down on their luck, pawn shops, and the like. It was a filthy, reeking, dangerous place at the best of times, even in broad daylight. Now when a major conflagration was licking at it, it was nearly deserted, for its inhabitants had nearly all fled to the lakeside, having little possessions of their own to worry about and try to save, being mostly transients and boarders and rootless riff raff.

Perhaps the reason why Alex chose to turn down the street into this quarter of the Patch was it looked free of traffic, compared to the other, more respectable streets. Whatever his reason, it was most direct, to get to the Sun-Tribune, though ordinarily he would go around the Patch, rather than risk being robbed and beaten up.

Running fast, with no thought now of looking like a gentleman straight from the pages of Miss Godall's Magazine, he thought he could be clear through it in a couple minutes at the most.

He could see the houses burning in the Patch, but gave them no mind as he trusted in his legs to get him safely across the armpit of Chicago.

But Ero saw the wind was shifting direction, blowing the flames back on that section which it had first overflown.

As if it was making up for lost time, the fire burned twice as intense, and the wind increased. A wall of flame a hundred feet high then descended on the very neighborhood Alex was crossing through. As it advanced down on him, he passed people, the last to flee, running past him, their clothes smudged black with smoke and soot, their hair singed, and their eyes bulging with terror.

Alex stopped to get his breath. He saw the fire was sweeping directly at him. He realized he had made a big mistake. He would have to run for his life now. He turned around, deciding to turn back toward the Y. What he did not see was that the fire would not be stopping for anything now. The previously scorched and burnt houses were like so much mesquite charcoal to the fire, and they were whipped into an inferno, rekindled by the wind and flames, and the fire rushed over the previous, half-burnt acreages and then attacked the buildings round the Y, and then the Y itself.

Ero watched Alex, with no where else to go, though flames were leaping up on all sides of the building, dash into the Y.

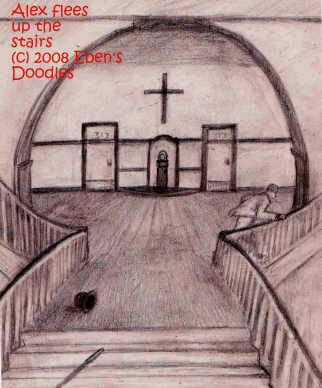

People, as firemen know, often do strange things in a fire. Alex ran up to his room, closed the door, then went and poured out some water from the pitcher into the white bowl at the wash stand, wet his face and hair, then dried himself on a towel and combed his hair carefully. Looking in the mirror of the stand, he straightened his tie and brushed his clothes as clean as he could with his clothes brush. It would have to do, he decided, until he could find a laundry to wash the suit and press it. As for his article, he left it where he had put it under his shirt. It was safe there, he thought.

Taking his cane and hat, he glanced around at the room, thought of taking his carpet bag and things packed in it, then dismissed the idea and went out, locking the door. He slipped the key under the door along with his due rent money for Will Withy to collect, then walked toward the stairs, drawing on his hat, squaring it properly and holding his walking stick in the casual but elegant way Miss Godall had instructed him and other young gentlemen with "prospects" in the world.

At the stairs, he was about to go down, but only took a few steps when he saw ugly, black billowing smoke boiling up from the first floor, heard a roar and felt a blast of hot air in his face, and he panicked. He turned and fled up the stairs, and just before he reached the third floor he dropped his walking cane but left it and his hat dropped off a few feet further, but he left that too and continued to the next stairs.

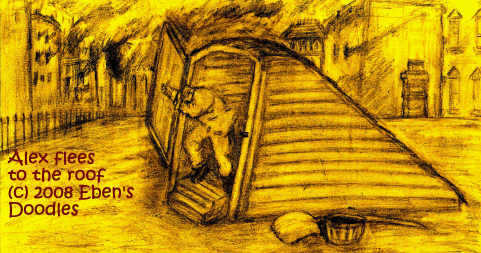

With Ero watching, Alex kicked out a flimsy attic door and got out on the roof just as some flames that had raced up the staircase jetted through the open door.

Yelling with pain, Alex struggled upright, his legs splayed in the slippery tar, and wiped his hands on his suitcoat to get the burning tar off, hating to have to ruin it.

Moving again even more carefully, he reached the building's edge, but there were no fire escapes from there, of course, since this was the street side, and he had forgotten that escape staircases would be along the building's sides or the alleys. He had hoped there would be--but fate (or impulsiveness) had dealt him a last cruel trick. He would have to scale down over the side somehow, he saw, to escape from there.

But what would he hold to? He was thinking desperately, frantic with the billowing, blistering heat and smoke around him, and couldn't see any way he could make it down the side of the building to the street safely. How he hated heights anyway--they made him dizzy, as he was subject to vertigo and, for that reason, climbing trees as a boy had never been his pastime.

He couldn't cross to another side either and try to get down from there, as the roof was not begininning to catch fire, and he had to get off it now or never, he realized.

The thought of GOD (simply that: GOD) just now flashed into his mind, and he just as quickly dismissed it. He wasn't going to betray his cherished beliefs now. No, not Alex! He had invested far too much in his own skeptical philosophy to throw it overboard now. He had taken a lot of trouble reading through the library at Bloomington night after night and on Saturdays, whenever he had time off from school and his work at the Courier. It took a lot of reading and brainwork to be an informed skeptic and atheist, but he had achieved it. He had made himself able to shoot down every argument ever put forward by Christians and theists for the existence of God, knowing the authorties who claimed to prove there was no God had to be right, since they had science and now Charles Darwin and Evolution on their side, whereas the God-believers had only ignorance, superstition, bigotry, and prejudice. "Priestcraft," chicanery in solemn robes taking advantage of ignorant, superstitious, unenlightened people for their money. That was all it was!

But why did this thought of God even come to him? He had no need of it, when he was facing certain death if he didn't do something fast. After all, if there was no God, which he firmly believed, then it followed that no God could help him in his extreme need--and so, ergo, he was completely on his own. But maybe it was the building itself. It was the main Chicago center for the Young Men's Christian Association, after all, and even as the chief venue of D.L. Moody's reaching out to the city's young men and street boys was burning up (to be replaced in a few months by an even bigger center) it had something to say about God--"God gives and God takes away, but blessed be the Name of God."

Alex had no such thought, but Ero did, observing all this happening before his eyes as the flying dome carried him through the last frame of the photo-file.

Alex's maiden article for the paper was soon to be consumed in the same fire that would claim its writer, in which Alex thought he had brilliantly demolished D. L. Moody's theology of God's amazing grace, using the arguments and proofs he had learned from Olney, Voltaire, Hume, Darwin, Huxley, and other great skeptics and atheists and outstanding figures of science, scholarship, and intellect. As for Sir Isaac Newton, the creator of Newtonian science and who formulated the laws of gravity--well, he was an exception, of course, believing devoutly in God. Best not to mention him, for the sake of the argument!

Even though written by an rookie reporter and the man under attack was greatly admired in certain quarters, Alex's daring challenge of the up and coming D. L. Moody would have provoked a lot of comment and attention if it had been printed in the city's leading paper and forum of public opinion. Chicago, being the town it was, always liked a good fight. But, alas for youthful presumption, his masterpiece of refutation and Moody-bashing burned to ash just as everything, including Alex the budding Sun-Tribune religion editor (for such position he aspired, thinking his education in skepticism and rationalism and his articles in the paper would be the death blow for Christianity in Chicago, including a ticket out of town for D. L. Moody, given time) turned to ash.

Glancing back, Ero caught one last glimpse of Alex caught inextricably in the Great Fire of Chicago that destroyed the city in October 1871. Backing away from the flames licking at his feet and his pants legs, overcome by the smoke and heat, Alex was beating at the air with his hands and suddenly topped backwards, falling head down over the side of the four storey building.

After a sip or two, she headed to the elevators of the North Tower. It was 8 0'clock. Her company's offices were staffed at nine. She was early, intending to review her input for a department presentation of Marsh, Inc. The elevator slowed as it passed Aon, then slid past most of Marsh and finally stopped at the 101st floor. She joked about that to other workers, saying that as rookie in the firm she still occupied the highest level. That was true, not including Cantor Fitzgerald, of course, who occupied the 101-105th floors, with only the restaurant above them.

As she walked the quiet and virtually deserted corridors all the way to her little office far in the back of her department, she had reason to be pleased with herself. Imagine someone hired right out of college and given six figures! She had just about gulped out loud when she read the salary figure. This was clear to her that she was highly valued, and much was expected. She was definitely on the fast track to becoming a upper level management department chair or even a corporate director! Her performance at college had told them all that--she was the star of her class, even though she hadn't been asked out that many times--perhaps she was too brainy for most men's egos to cope with--whatever it was, her career mattered most to her at this time in her life. Marriage to some important stock broker could wait while she reached for the highest, biggest plums on the corporate ladder of Marsh Inc.

Having worked there only a couple weeks, she was just settling in, getting her office laid out as she liked it, and so hadn't gotten used to the WTC's size yet. It was like you took a whole city and squished it upright into two tall columns. It really had everything, she had no reason to go out for anything during her working day. Only the coffee was the standard office stuff--which she loathed, preferring her own espresso.

It had already been approved by her supervisor, after she had submitted it, so there was scarcely any chance of a slip up. Just in case, she scanned the most important sections.

She broke off for a few minutes, remembering to check her voice mail and any other messages. Planned Parenthood contribution? Of course--the U.S. consumption of the world's resources and the dependence on oil for car fuel needed to be greatly cut back, along with their being far too many babies born to poor black single moms in the inner cities...

She text messaged back, donating and renewing her membership with double the previously pledged amount.

The Democratic Party? What did they want? No, she had no time for active roles in political causes, but she could donate now that she had an admirable salary coming in and just herself to spend it on. There were a few other messages--but she needed to finish with her review, so she left them for later.

Tired of sitting (or perhaps she was a bit nervous), she rose and stood against the window frame nearest her desk. It was 8:46. She heard a loud sound. Strangely, it did not go away. It just got louder. A plane approaching the towers? she wondered. But they weren't in the flight lanes, she knew. So it couldn't be a plane.

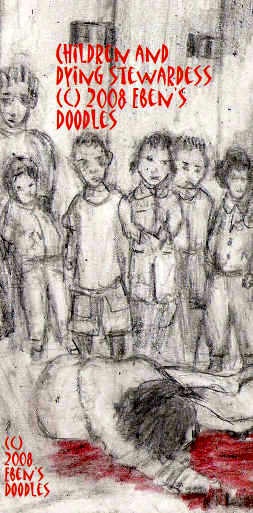

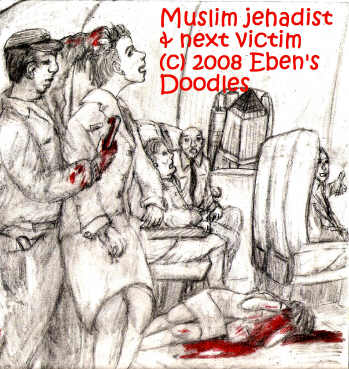

Meanwhile, the others took care of the stewardesses, who had been ordered to take all the children to the rear of the plane, which they did. One after the other, the stewardesses, still pleading for their lives, were dispatched with the same bloody wire cutters that they had used on the captain.

The children were stunned and dismayed, and did not know what was happening, why men should hurt the stewardesses so that they lay and writhed on the floor, covering it with blood until they quit moving.

It was all they could stand to see the stewardesses sliced at the throat like chickens in a grisly slaughterhouse, slain in cold blood, but the whole planeful of people, their lives, were hanging in the balance--and so the men who were able to do something hesitated, and hesitated some more--paralyzed by the thought they might only make things far worse for the people on board. "Don't you dare do anything!" one woman told her elderly but still physically fit husband, pulling him back, when she saw he was prepared to go it alone if he had to in putting up a fight. "You'll just make things worse!"

First of all there was a tremendous noise and shock to the tower, and it lurched, swinging out in a sickening movement that took a long time to stop--and for a moment or two it seemed the tower might just keep going and topple over. But it didn't fall over, and it moved back into place with all kinds of grinding, crunching, crashing noises.

Two such gigantic moves affected the whole interior of the 101st floor. Everything that could fall did so--even big planters crashed over on their sides. Desks moved, and desktop computers and laptops slid off onto the floor, along with anything else not nailed down. When the building stopped moving, there was a silence, which was deafening in a way, since everyone who had survived was shocked or terrified. Another terrorist attack? A repeat of the botched one in the 1990's which nevertheless killed four for five people and sickened 4,000 with smoke inhalation?

Those who knew it was really serious--or were nearest the flames burning in the heart of the tower--began to scream, though the screams Kaitlyn heard were faint and far away, and the people on her floor of Marsh were too few and separated to make any voice contact during the first minutes.

She was on her own, she realized. The power had gone, and she would have to take the stairs to escape.

Her knees felt a little weak, and she paused. She was a little confused, not sure just what was the best way to the stairs, for should she go to the right or the left? Which was best?

She started feeling her way, not sure she was going right, and only then realized her shoes were missing. She couldn't stop to find them. She also felt the floor was sloping, it was not even.

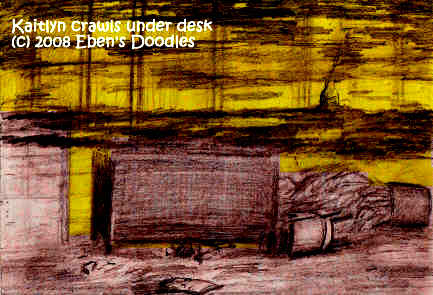

She did not reach the stairwell, wherever it was--as smoke drove her back, stinging and blinding her eyes and making her choke, so that she was forced to crouch, then crawl while holding her breath as much as she could. With all the smoke pouring into the room, she decided maybe it was better to lie on the floor and wait for help to come. Surely, help was on the way.

She crawled under a desk. Only then did she realize it was no sanctuary and she could not remain there. The floor was already oven hot beneath her, and getting hotter by the second.

At first it was not apparent what exactly had happened to the Pentagon--the secret services and top policy people and the White House War Room were caught mired in an imbroglio of misinformation, each jealously holding back its own piece of the top security puzzle, so that no decision could be made regarding the impending attack, which they all knew was coming sooner or later.

A bomb? Could a plane have overflown the airport and crashed? But Manhattan's troubles with the North Tower, on fire and sending a smoke cloud to the heavens after an American Airlines jet with full tanks of fuel plunged into the upper floors, was already known to some in the Capitol and to even more in the various secret services and in the top echelons of the Pentagon. What they did not know is that Pentagon was just as vulnerable to the same thing that had struck a mortal blow to the North Tower of the WTC.

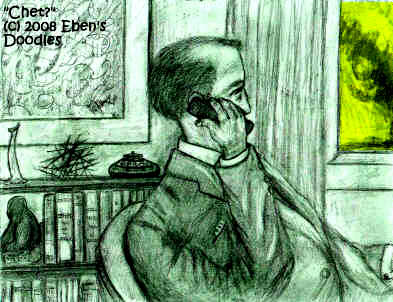

The man in the art-choked office was staring out the window and observing the tremendous plumes of dirty smoke pouring across the city and filling the horizon when his cell bleeped out the first bars of Beethoven's Ninth.

"Remember, no recording and tracing this--right?" "Of course, I wouldn't think of it." There was a pause. "Well?" Chet coached Deep Throat II.

Deep Throat II: "I suppose if I have to deal with a lying devil, it might as well be you as someone else. I know you have always traced me, but I know to keep one step ahead of my, ah, clients. That's why I have lasted as long as I have."

"You didn't call to tell me this," Chet interrupted, a bit annoyed.

Deep Throat II: "Of course not! Have you noticed anything unusual going on outside your office--that smoke cloud coming from the Pentagon, for instance?"

"How could I miss it? Well, what about it?" Deep Throat II: "Aren't you concerned?" Chet laughed. "Why? What goes on at the Pentagon is a problem for the Secretary of Defense that runs it. I see no reason to take any personal interest in another department's affairs and purview of responsibility. Let them deal with whatever is happening over there. I have my own duties--"

Deep Throat II interrupted, "Oh, but you may have to be involved, whether you like it or not. What if the White House, or both houses of Congress were hit next. What then? Might you not be affected?"

Chet seemed to take more interest, as he paused before he responded. "Okay, tell me more. I'll send your stipend to the usual outlet, or name another that better suits you." Deep Throat II (amused): "You might have to pack your toothbrush in the next few minutes, and take a private flight out if you can, as all the roads are jammed. It is going to get worse soon, when the next plane arrives with 14,000 gallons of high octane."

Chet, leaning forward, was furious: "Quit playing cute with me! What place is next on their list? Spit it out! You're being paid for information, not talk, talk, talk!"

Deep Throat II: "All right, all right, since you are in a rush--my best information says it will be the White House in order to take out Number 1--though they may change their minds for a secondary target. Look for it to happen around 10:20, with five or ten minutes give or take."