Before Victoricus left, he had shown Patricius the post mail, the many letters, he had come to deliver. He handed Patricius one of them, and Patricius read the heading, "The Voice of the Irish." As Patricius began reading further, he could hear the voice of the very people he knew living near the wood of Foclut, which is beside the western sea, and they cried out with one voice, "We appeal to you, holy servant boy, to come and walk among us!"

“No, no!” Patricius cried amidst his tangled bedclothes, as he struggled to throw off the call of God on his heart and life. But it was true, he knew, he could not deny it, that Erin, the land of his own cruel enslavement, was calling him back! It was terrible to think, but God Almighty was calling him to go back to the very people who had enslaved him and made him work long years, torn away from his family and fine home in Bannavem Taberniae.

Then, realizing that he might wake the whole household with his groanings, Patricius flung out of his bed, staggered to his marble and walnut wardrobe, and found his cloak and a robe, threw them over himself, and grabbing his sandals went out of the house into the night. He had to get away a distance, where he might be able to think more freely.

The grass was warm to his feet on the banks of the River Severn, for he left his sandals behind and continued on down toward the water. He realized he was treading the very spot where he had been captured by the Irish sea raiders years before, when he was a young but godless and pagan-living boy aged sixteen years, the heir and first born son of a Christian home. This made him stop. Though Britannica was increasingly beseiged by hordes of wild, heathen, plundering Germani tribes on the west and southern coasts, here in the extreme west as yet there was no fear of such happening to him again, for he was grown into a man, and would not go meekly unresisting as he had in the past. How glad he had been, even in the hands of the rough slave-traders, that he hadn’t screamed for help, leaving his family safe in the house. If his captors had guessed that his rich and beautiful home lay so close by behind a sheltering curtain of thick oak and beech trees, and without a standing watch and guard and undefended, they might have raided it too and all his family taken!

That thought--that he had saved his unsuspecting beloved family by not crying out--had sustained him all through the next horrible days and years. He could have cried out for help and brought his servants and his father running with torches and weapons--but he had kept silent. What had they thought, when they found him gone in the night, and not a sign except the footprints of men and the mark a shipmaster’s shallow-draught harbor boat makes on a grassy riverbank when it is drawn up?

He had to wait long years to find it out, when he was back home safe with them again, asking and being asked many questions between the embraces and kisses and tears of joy and relief.

His thoughts and feelings tumbled now worse than they had that fearful night of his capture. Why had he gone out at night and exposed himself to the brutal slavers? Why, he had been such a foolish lad back then? It was only for a lark, to be out and running about when decent folk such as his family lay abed after their final prayers. And how it had cost him! He had sinned greatly once too many times, running about with wild-spirited boys from the town, though he knew the commandments his father, the deacon of the church, had faithfully taught him as his son in order to succeed him in the holy office.

Yet he had scorned sober fatherly counsel and God’s commandments and even God-imparted sense, though not saying so in impudent words. He had followed his impudent heart to his own moral ruin, careful to keep his innocent family unaware of his secret sins.

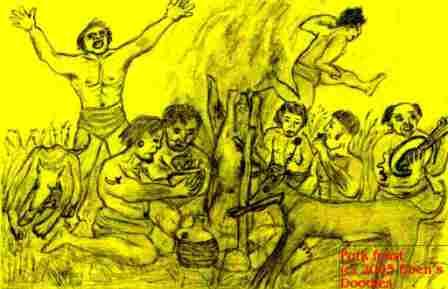

Here he was a city magistrate's and deacon’s son, ordained to follow him in the holy church, and moreover was of the noble blood of the curiale class of Rome--sinking so far as to go rutting like a filthy hog in a beastly rite that only the lowest-born of the land relished! What was it in his heart that craved that horrid practice and led him to shame himself so basely before the foul and obscene gods of the heathen Druid priests of the ancient Britons? How he had loved it, relished it, evenso, to weave leafy vines and and mint and berries his in his hair and dance naked-limbed, and drink warm bull’s blood from a horn beaker, and get drunken with the lust born of fire and shamelessness and dancing with pipes and flutes before demon gods! How the white-robed Druid leading the group had heaped highest praise upon him for coming, naming him and saying, "Welcome, welcome, 0 honored son of Cothirtiacus, which is your family name of renown for your forefathers' serving four houses of Druids! Your forefathers were faithful to death to the high gods--and now, you have returned to the holy pieties your family formerly served!"

What a vile, sneaking little hypocrite he had been, meeting Lady Concessa his mother’s eye with his own shameless, clear-eyed guile though he still felt dirty inside.

Vain and shallow, craving sensation no matter how evil and degrading, he turned himself into a child of darkness, all the while acting like a child of the Light and the Kingdom of God. Faithful to creed and sacraments by day, but engaged in Druidic revels by night, he was yet so young that no tell-tale taint or stain of his corruption showed upon his young face and person.

Once or twice, becoming convicted by what he really was and what he purported to be, he had vowed not to go out again--but when night came, that terrific tugging in his wild heart came on him like a practiced whore in Londinium's port, taking his hand and drawing him forth with growing excitement into the night. It was like a poppy drug in wine he could not resist, night after night. Self-loathing could not stop him. He loved what abased him, and wallowed in his abasement like a gutter pig in the slops of the midden or a dog in its own nasty ordure.

Why had he gone out at night, so that he had been taken by the Gaels of Erin? Of course, that was one question he could not openly answer, even when he returned home. How could he shame his rejoicing parents and family with the fully confessed truth of his sin and paganism? No, he had vowed never to tell any living soul what he had done secretly, defiling himself with the base worshippers of fertility gods.

Patricius went to a patriarch, a great oak tree, leaning upon its trunk. His hands fell limp at his side as he relaxed for the first time since the vision broke into his sleep. He recalled, not the vision, but his family’s astonishment a week before when he stepped ashore and ran into the house yard past the speechless gatekeeper, shouting “Mother! Father! It is I--Patricius! I am returned home! Home!”

Having believed him dead and shed a thousand years, his mother limped to a chair to sit, her face pale and her breath gone. His snowy haired, prematurely grief-aged father too was nearly struck to the ground, for he staggered at the sight of his son returned from the grave! It was a terrible moment for all, but it swiftly turned to wild joy, as they recovered and flung themselves on him. How they cried and shouted, and it brought everyone running. The little town all around was emptied of its inhabitants as neighbors and townsfolk, with servants, all rushed to see the return of Magonus Sucutus Patricius, the long lost son of the highly respected magistrate and deacon, descendent of the revered Potitus the priest, whom everyone had presumed drowned, or slain by some drunken robber passing by the town.

“Good Calpurnius!” someone had cried. “Have you lost your mind? Your son is dead!”

“But I am not dead, I was taken by raiders and sold a slave to Erin!” he had wept into his father’s ear as his father nearly crushed him in his arms.

Now Britannica was not a sentimental society, so the emotions, when they came forth, were violent and wracking--all the more powerful, since they swept aside all the reserve and restraints of the Romans and the Church life--pouring out the very heart of the Celts of old--all their pain and longing and inexpressible heart-speech. When his Latin failed him, as it soon did, Patricius broke into Gaelic of the Celts and Britons, which he had not spoken for years in civilized society. Finally, after his heart had said what it must, he returned to the proper Latin.

“I have come as soon as I could get away from my owner! Forgive me, dear father, I could not write to you! I had no pen, no paper, no ink, and no post courier to take word to you!”

My, the tears, embraces, and the noise as everyone made much over him and what had happened! Soon word spread, bringing more people to see this marvel of a son raised from the dead, until his father had to shut the gate or the house would have been overwhelmed with the multitude. It took hours to clear everyone out who was not in the immediate family. How badly his father and mother and two younger sisters wanted to have him alone, and to get him fed and clothed properly. He had come garbed like a slave and evil heathen, and his father dashed away at one point and returned with his noblest robe, the scarlet-bordered one he had worn in Rome on a visit to the imperial court when it was still in that city. Everyone gasped as his father put it round his shoulders. “Father!” Patricius had protested, but his father insisted. “My son was lost, but now is home at last in my arms. Take it, my beloved!”

Then his father had kissed him, slipping on his hand his own noble curiale’s ring.

Patricius’s hands went to his eyes, for they were drowned in tears, at the thought of that wonderful love his father had shown. Then other hands, just as loving, brought him the best wine, and the most beautiful sandals, and led him to the finest, gold-embossed couch reserved for noblest guests such as the Roman governor of the province, and it was one continual feast, as fine things were brought from the kitchen.

“We nearly starved to death over in Gaul and Gallia Belgica,” he told them. It was his story of how he had gained release, by taking ship from the coast of Eire with some dog traders going to the big marts of Narbo and Boulogne if they could find them still unravaged by the barbarians.

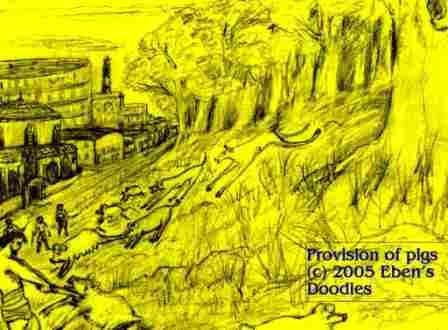

The shipmaster said to him, “How is this, O Christian? You say that your God is great and almighty. Why then can’t you pray for us, for we are in danger of starvation? Likely we shall never see a human being again.” Then he said plainly to the shipmaster, “Turn in good faith and with all your heart to the Lord my God, to whom nothing is impossible, that this day He may send you food for your journey, until you be satisfied, for he Has abundance everywhere.” Saying that he had fallen on his face, praying just as he had prayed back on Croachan Aigli, on the Slemish mountain, for deliverance--and Almighty God had answered! Immediately after his prayer, the men had heard sounds of animals in the distance, and they ran toward it and found a whole herd of pigs that that been running wild and now were being chased by some wild dogs! It was all the food they could want.

With this wonderful miracle, the men were now all very open to hear about his God, Patricius found, for they asked him repeately to speak, feeling ashamed of their base lives and their foul living in the past.

“But can such men as we be saved if we have worshipped other gods, which we all know to be vile and false?” they had pleaded. “Certainly,” he had replied. Having found grace himself after his foul sins, and been granted deliverance from slavery, he could offer the same to the dog merchants.

“Throw yourself on your faces, men, and implore God’s mercy and grace, and He will hear you and forgive your black hearts and black deeds.

Turn to the only true and holy God, be cleansed by His blood, and He will turn lovingly to you! Christ delights to save wicked men, which we all are, and deliver us from the snares of devils and the temptations of vice.”

Grace! Grace and forgiveness for the likes of them! Full cleansing! How these simple men had wept in joy, believing his words over there in the wilds of Gaul! He was thrilled afterwards, as he told his family how the men had converted from dark gods to the unspeakable splendor of the Christ, God’s Holy Lamb who had shed his holy blood for their sakes, taking their full penalty for sin and idol worship upon Himself.

His father, hearing this account, seemed as if he had not heard his son aright, he was so amazed, and his dear mother was evidently confused.

His father spoke first, in most gentle remonstrance. “But son, you were half out of your mind from the barbarians' ill treatment and lack of proper food and shelter. Imagine, such feasting on undomesticated, wild pork! You might have gotten very ill! And did you really promise salvation to such uncouth, low-bred men as you describe?”

Then, cutting her son's heart to the quick, Lady Concessa followed. “Oh, surely not, my dear sweet little Magonus Sucutus!” Her eyes turned up toward heaven in shock, as she raised a scented hand to the jeweled and golden cross hanging at her neck. "Such heathens are not fit to receive the unadulterate Grace of our beloved Christos!"

Patricius, for a long moment, could hardly believe his ears. Then hot blood had flooded his face at their pious but mistaken reaction.

“Oh yes, I did just that, promised them the same as I, a sinner, had received from the hands of the bleeding Christ! How could I not, beloved mother and father? Christ Himself would reprove me if I had stayed His grace from reaching these poor, perishing souls! How can you then reproach me in this? Surely, you know Christ whom you serve would approve and do the same to the lost? After all, he died for us, gave his life for us, even while we were yet his enemies and lost in our sins, did he not?"”

“But--” his mother protested, throwing up a fine, pale, blue veined, ringed hand while his sisters gazed at him with utter bewilderment.

“Yes, yes, “ his father assured him, “we quite understand your speaking so to them, it was the only thing to say to gain their favor and confidence, so that they might let you go home peacefully to your own country. God, of course, will overlook a youth's indiscretion and prodigality in things of our religion due to the hard circumstances you found yourself in.”

Then they had hugged each other again, but when Patricius finally retired exhausted to his own chamber, he still wasn’t satisfied that the matter was understood properly. How could they objected to sharing the Gospel with the men who had helped him escape from Erin?

It wasn’t right, he knew in his deepest heart and soul. Were they so righteous and good, that they had forgotten no human soul is righteous before a holy God without the cleansing blood of Christ? Before a holy God, no man can possibly be holy or produce righteous deeds of his own that would possibly turn aside God's wrath. How could they forget that? These were elemental truths!

Patricius thought some more, and then the understanding, sad as it made him, dawned on his mind. Faithful to the holy creeds and sacraments, all the ordinances of the Church and the office of deacon, his cultured, noble-blooded parents stood above the mass of common people, not able to even admit that pagan orgies took place in the groves along the river and other places as well. They lived in a refined illusion of their own making--not aware that God saw things far differently than they. Why wasn't he as self-deceived then? Patricius wondered. How could he be right and his parents wrong? Yet he had known of Christ’s sacrifice for sin and love for sinners since he was a mere child reciting the holy creeds of the church fathers dutifully.

Then, becoming a sinner worse than anyone he knew, it came back to him when he needed it most, when he lay naked, bound and puking in the stinking, urine-scented bilge of a slave trader’s boat on the way to the sea and an unknown destiny. How he had cried silently in his soul, fearing the lash of the traders if he made any noise! He had wept God’s merciful name over and over, knowing he had mightily offended the God of his fathers, that he should suffer so sorely in his tender youth. “Christ, save me, a sinner!”

What were they going to do with him? He was terrified and could not restrain his body functions, calling down the lash upon him by the sea traders and their worst oaths. He must have prayed that a thousand times before the boat finally stopped tossing on the open sea and gained quieter passage on some river estuary. By that time a peace had come to him as well--it was like a wing of a giant bird spread over his tortured, guilt-ridden spirit, calming him, telling him that all was well, he was not damned but saved by God's sheer grace in Christ, he was not foul but cleansed by Christ's blood shed on the Cross for him, he was not forsaken but reclaimed by Christ's work of redemption and perfect atonement!

For this peace was confirmed by certain words he realized had to be holy scripture forming unbidden in his mind: “Do not fear, for I am with you, do not anxiously look about you, for I am your God. I will strengthen you, surely I will help you.”

Later, he found even greater need of such words and assurance. After receiving thrown buckets of stinging salt water to clean his muck off, then staggering with a greasy rope around his neck and his hands tied, he was led to an improvised slave market at a stinking hogsty of an Irish camp and market called Merrie Bough. His worst fears were not equal to Merrie Bough.

Thrown into a wattle keep in which pigs were thrust for the sale, he found himself prodded with sticks and staffs by dozens of prospective buyers who haggled, bartering a wagon, or a head of cattle, or some sheep, or Roman coins if they had them.

The obscene joking and prodding by the barbarian tribesmen at his buttocks and privates, the public disgrace and shame, were harder to bear than the capture itself and the sea voyage. All through the ordeal that most sorely tried his soul and his belief in God his Savior, he had found his only sustaining comfort in late-found assurance that God had accepted and answered his desperate prayer for forgiveness of all his sins. By that assurance gained in the bottom of the sea raiders’ boat he knew he had truly found divine grace and been acknowledged in heaven as a child of God! Before, at home, he had routinely mouthed the pious words of grace and sonship during church services, but now the knew them for a saving truth!

This knowledge had sustained him through all the dark experience of his public sale, and the brutal handling he got from his new owner, Milchu, a warchief of some considerable rank. Important and possessing more stock and pelf than he needed, with too many cattle and and small cattle and pigs for one man to manage, he looked for every available herdsman he thought he might trust to keep a flock in some solitary place alone (for he did not trust two men together not to feast not to drink or take women with them and carouse).

Churlish, Milchu thought he had paid too much, when he found that Patricius was an ignorant weakling from some foreign British town and could not speak proper Gaelic, knowing only a few cuss words picked up on his passage to Erin.

For Patricius, his destiny soon turned to forced labor that came from being a despised foreign captive. So Patricius was made a herdboy on a mountain slope, day after day, year after year.

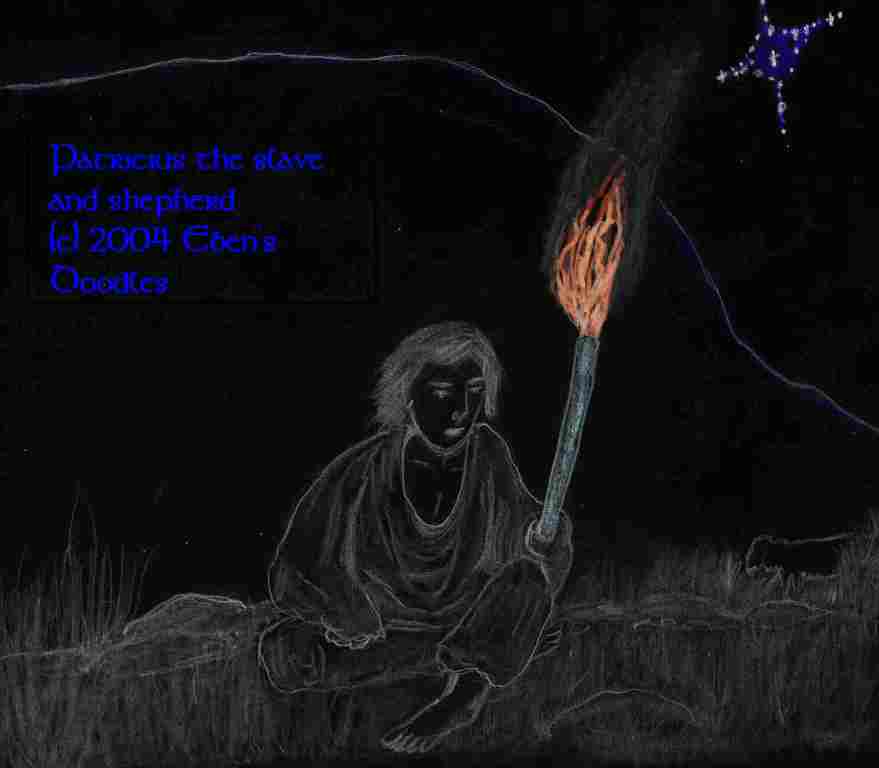

Yet his master Milchu, a warchief in north Dalaradia, was too busy to watch him continually, and he was able to pray unmolested to God, hundreds of prayers in a single night, not stopping for any rain or stormy wind.

He would sit with a burning faggot in his hand, if he could manage some wood and dry tinder for making a fire. That briefly burning, warming torch was the only physical luxury he knew in his sojournings as a shepherd and slave.

The details of the past weeks, interlaced with his memories of his six years of captivity, flooded back into his mind as he leaned against the big oak tree. He was not despairing now, as he had at first on his arrival, only to find that God was with him even in the fell darkness. No, he was rejoicing, that God kept him alive until the time the Lord came to him at Croachan Aigli on the mountain, declaring in a dream it was high time for his deliverance, and that he must run away to the coast, to a certain spot by a headland shaped like an adze-head a ship would be waiting to take him away from Eire. How wonderful that word from God had felt!

He sat down by the tree, while in his mind's eye he was back on the mountain in Eire, praising God for his deliverance and God's word just come to him. Then he was so surprised when a bright shining being appeared that he fell forward on his face.

"O son of the Phoenix, why are you lying there and tarrying? Get up, play the man, and go find your ship, and escape from this place of your testing and travail!"

Springing to his feet, Patricius had found no one there, for the bright shining one had vanished. He still looked carefully around, seeing the pigs and sleep, and it seemed he woke up--what, indeed, was keeping him there in that awful place? The voice had spoken truly. He owed Milchu nothing. He need not stay. He still had good legs to run with, he had a free spirit, he could run away if he chose. After all, he had not come to Milchu's pastures and pigpens by his own choice, had he!

It was such a thundering revelation! He realized he was a free man after all! He need not remain a slave--unless he chose to be a slave! Laughing at himself, he started running, and soon put Milchu's grazing lands and herds far behind him. Only the Lord had not told him, mercifully, that he must first endure more trials. Yet there followed miracles, such as the one in Gaul that fed the ship's captain, the mariners, and himself and the dogs so abundantly.

Though he knew others hearing his story might be skeptical, and question whether God had spoken to him in a light, or even arranged to set him free, he knew better. Hee could not get over the marvelous miracle of his deliverance, that started really with the ship that carried him to freedom.

He thought again and again about it.

Just finding a seagoing ship touching on Erin's coasts was a miracle in itself, was it not? Erin was an altogether unproductive, hostile, barbarian land with scarcely a city and few merchant ships, ruled by fierce, barbarian chiefs who worshipped gods of the rivers, spirits and devils of the rocks and mountains, and deities of the trees and even of beasts. These last worshipped goat-gods and sheep-gods and even serpents! The whole country did not know one single city sewer drain or a pipe carrying clear water to the household! Everything Bannavem Tab. had and took for granted--was utterly unknown in Erin! And no wonder! It was a foul, dark, idol-ridden land, far worse than any residual dark corner of Roman Britain in every respect, except that it was so green and lovely from the many rainfalls.

How could he find a ship that would be willing to take him home from such a forlorn place? They would want to enslave him at first sight and sell him in the nearest market!

Yet he found the very ship he needed anchored by the coast, exactly where the headland jutted out in a shape of an adze, and the ship's mariners were ashore in a camp by the side of the small harbor on the sheltered side.

Yet he didn't know them, and how would they respond to his request? It took all his faith to obey the word of God and go to them, pleading for favor in their eyes and safe passage to his own country.

Desperate, since he was a boy utterly without money and possessed nothing to recommend him, he did what the custom of the time required of a slave. Gagging as he did it, he had suckled the captain’s own dirty, hairy chest according to the well-known, ancient tribal custom of barbarian Erin when one sought special favor that could not be gained any other way. It had make him, a civilized Romano-Briton, almost retch to do it, but the Celts and Gaels demanded such homage from inferiors and aliens if they wished to be granted their request, whatever it was.

Though casting him a sidelong, cold, fishy eye at the onset of Patricius's approach, the captain seemed to be a bit more favorable to him once Patricius had humbled himself in that slavish, abject way.

“So you want to join my grand vessel? Well, we are passing over this stinking water, the god Thor’s urine stream, to yonder Gaul,” the captain had told him sourly in the Gaelic tongue. “You are no use to us aboard, unless you can help care for our cargo. Are you willing?”

Patricius, hearing the yelping of many fierce dogs bound in cages or by ropes and foot fetters in the hold, felt his heart sink.

“But I herd sheep and cattle and pigs, whatever my master gave me to tend, not ever such unclean dogs!” he had blurted out.

“Well, that’s no blasted good for us!” the shipmaster shouted. “Begone! I can’t take on passengers without pay or a valuable service in kind, such as gathering their turds in a basket. If we happen to fare as far east as Londonium, the tanners there will pay us well, if we don't first get cast on some barren island and require them for our own provender!”

The mariners, listening, all broke into the most fiendish laughter, and Patricius would have dispaired, and shrank away, but he remembered something. His seal ring, given him on reaching his majority!

He slipped it off, which he had saved by hiding it in his mouth when he had been captured and stripped naked. This most precious possession, the only thing binding him to his former life, he then offered for his passage.

Eyeing it carefully, then biting it, the shipmaster seemed impressed. "By Thor's whoring wife and bastard sons, what stone is that? A real jem? And the metal is gold too, I believe. By the gods, how did you come by it, lad? Steal it from a great chief or nobleman or his lady?”

But the captain had taken it, and let him on-board the ship, telling him, “Keep out from underfoot, lad. You just ride this trip, and we’ll do the work. After all, a fine nobleman like yourself, who bears such a princely ring, shouldn’t have to work!”

Then the captain laughed, and all the men laughed, and Patricius, taking his cue, laughed heartily too, and the matter was settled. He was going with them after all!

Patricius wanted to tell him the truth, but the captain hurried away to his own duties, leaving Patricious in his awe over God's miracle with the dogs.

“Devout youth, remember me to the God of heaven!” the captain had shouted over the water. “Remember me!”

So he had! He had prayed for the men and their captain, for he owed them very much in restoring him to the sweetness of his home and family. But now that he was home, it disturbed him strangely. First his father and mother’s estrangement from his own experience of God’s infinite grace in Christ--that was troubling him even as he fell asleep. Then the vision! It shook him to the core.

“Come and deliver us, holy youth, bring the light of the Gospel to us in darkness!” the heathen Celt from Eire cried to him in the Gaelic tongue of that land. How could he shake off that plea? How?

Throwing himself away from the protecting oak, Patricius started on the path that led up along the river toward the neighboring city of Glevum (which connected by road to the main thoroughfares and cities of Britannica), but he came to the spot where the foulness of old deeds stopped him in his track.

“It was here I proved myself the most rank evil-doer and Christ-deniar,” he thought. He shuddered, seeing in his mind’s eye the burning fire of faggots, the horn beaker held out to him by a stark-naked old man with a white beard who gaped at him like a fiend, and the wild, dancing men and bare-breasted women urging him on to worse excesses.

How great a salvation! How great a deliverance! He knelt down, his face flooded with tears of gratitude, and the issue was settled there once and for all. Standing on the very spot of his former infamy, where he had defiled himself with abominations beyond saying, he was anointed afresh, not only with the sense of sweet communion with God, but with the full assurance of that his depraved soul was cleansed , saved, and sanctified by the Holy Blood of Christ.

In exchange, he could only cry out, “Thy will, O Lord my God, be done, not mine!” For what might he render to God for his benefits, for salvation and deliverance from sin and slavery? He had only one gift to give: himself. He would devote his life as a servant of Christ and the Gospel. He himself, he realized then, was the only thing he could give back to God. And it was to Erin’s tribes he would go , God going with him just as He had gone with him before in an evil day.

Swaying unsteadily, but finding new purpose and meaning with every step, he turned resolutely toward home.

When he stepped back into the yard, it was as if he had returned to an alien lodge.

He felt, deep within himself, that home now lay somewhere afar, in the direction of Croachan Aigli’s high, wind-swept and rocky clefts. And with that feeling a burning urgency flamed in his heart, to go and tell the glorious news of the Lord’s grace to the darkened souls of that beautiful, wild island. No one in his family, he realized, would understand his call--a personal call from God. They would not fathom it at all, but he knew he must go at God’s call, or be wholly false to all that had happened and all God had done for him. He resolved to go, no matter how they opposed him. “Let them think I will become a priest, for I will go first for training in the word of God to some school, but I will afterwards return to Erin’s Isle!”

So, it was. The family reluctantly let him go when he explained his call to a holy life and a need for religious training, something his native city could not give him as it had no monastery.

And the years he spent at Lerins, a monks’ school on a flower-bright islet in a yet unravaged part of Gaul, and at Auxerre, the seat of the good bishop who had come and let the Britons to a great victory, where he was ordained, were well-spent. He took voyage to Erin from Gaul, and never returned home to Bannavem Taberniae--where no longer anything held him, neither family tie nor bond of loving memory ever since the Cross of Christ, and His Gospel, took first place in his heart.

No, rather than the white-washed sepulchers of his town’s dead works-righteousness, the Cross of Christ his Savior was, along with heathen Erin, his true heart’s love forever!

All while he lay a sin-sick captive in the bottom of the sea raiders’ boat, the Cross had fallen on him and consumed his flesh, setting him free from not only a depraved nature but the greater sin of pride and self-righteousness.

Set free spiritually, Erin’s people became his own, and their well-being his chief aim! He returned a slave’s wretched gift, himself, and gained a great extraordinary recompence: a share in the golden destiny of the Messiah. All Erin forsook its gods and turned to the only true living God he preached lifelong to them, and became a light to the nations that shed its beams across half the dying, old world before the light passed to other torches! A slave’s poor gift--that was all he was--it was all he possessed to give unto the Lord and the people of Erin, but it was enough. It proved enough.

So he did lay it and his mantle of arch-apostleship down--and an appointed bishop, who had shown great fidelity and courage for the Lord's work, received it humbly on his knees in one of the new churches as hundreds of the Lord's people looked on and prayed and rejoiced.

Many wept continually as well, for they knew this was the sign that their beloved and aged Padriac, the shepherd of their souls, was leaving them at long last.

Would he return to his native land, which was now sinking in the heathen grasp of the foreign Germanii, except for some small patches in the west and south and north?

But Patriac answered the question by retiring to a small, lone shepherd's hut.

He could have lain in any of their warchiefs' finest lodges, but this bare, poor hut was his choice. A few elders and deacons stayed close by, ministering to him day and night, as need be. But the time came quickly as they were praying, not suspecting it--and sleep closed all their eyes. Padriac raised himself up partly on his pillow. He knew he had come to the final moments of his apostolate and life journey, and that he was lying upon his deathbed. As all life in the blood withdrew from his limbs, leaving them icy cold, he was not alone, though the elders and deacons had fallen asleep outside the hut's door. Instead of an elder, someone else stepped in the hut. Introducing himself, the stranger spoke. Padriac was surprised to find that his guardian angel’s name was, strangely, Hebrew.

“Tsaddiquim” which meant “Ye Righteous,” spoke to him most tender and gracious things that stirred his heart and spirit mightily though his body lay cold and dying.

“You have brought, O servant of the Most High, and offspring of the Phoenix, an entire nation into the everlasting Light of Christ! Turn now, faithful one, to your place of rest and honor, until crowns be given you by the Holy One! And know that you will be seated upon a throne of judgment when this people beloved by you as your own are judged for turning away from the Lord's Gift of Light and Life--for they will turn away. But do not grieve over them on that dreadful and wonderful Day, for there will be many before the End, and even at the End, who will suffer martyrdom for the Lord's Sake who were first won to the kingdom because of these same folk, before their sons and daughters turn away!”

So spoke the majestic angel to him. This figure faded away, but then a far greater Light appeared, the Glorious One Himself. He who bore nail-pierced hands and pierced feet smiled at him with joyful face and swung wide a golden door before his eyes. Christ Yeshua’s own hand drew Patricius forth toward the glories of paradise...

Master!” the former slave and shepherd boy, and later esteemed as Eire’s patron saint, cried. “My beloved Master, receive a profitless slave!”

And his Master, the Lord God of hosts, responded with a word from the holy Psalms: