It was April, and they had just a few more weeks to go at the Institute before their final exams. The money gift that came from Carol’s parents so unexpectedly, with a note to enjoy themselves on a vacation if they could get away from school for a few days, made it all possible. They had been so strapped in finances up to that point. The money would only pay for the trip but would keep them eating while they finished school. It had been hard in Paris, with the high cost of everything. They had lived practically on bread and cheese and tea the whole two years of their stay.

Carol, her head covered against the light rain with a brilliant red scarf, glanced over at Ron, who was burying himself in his book and ignoring the Parisian scenes flitting by the window.

“Hey!”

He turned to her slightly, his eye still holding its place on the text of Karl Barth’s Dogmatica profundica, Volume II.

Carol’s eyes darted rapidly from the scenes of the great city she had not yet grown used to even after two years of impoverished studenthood, fixing on his book. Paris never slept, of course, but at that time of the morning it was showing extra bustle. People were weeping on the street corners, hugging each other as they clutched issues of papers with Edith Piaf’s name plastered all over them.

“Can’t you put that boring old thing away for even five minutes?” she fired off at him in French, having cried all she was going to cry for the favorite French torch singer. “This is our vacation! Let’s enjoy it and live a little!”

Disgusted, she let him go, and turned to watching Paris show off all her colors, charm, and chaos in the avenues and streets through which the bus sped. Much as she loved the faded old queen city, she was relieved when they passed through the suburbs into the open country and saw farms and rural scenes for the first time.

She turned to the tour map that the driver handed out to them on boarding.

“We first going to see Giverny!” she said to Ron, who made no indication he heard her. “Monet’s Gardens no less!”

A furrow appeared in her brow as she looked out. “I hope this rain stops!”

She couldn’t budge Ron from his book even with mentioning Giverny and Monet, so she gave up and turned to her own books for the remaining time on the way to Giverny.

If only she didn’t love Ron so much, if only she didn’t love Christ even more—Paris would have been a great temptation, she knew. Women ruled, and men were their slaves (or pretended to be) in Paris! A beautiful woman could seemingly write her own ticket—just as little Edith Piaf had done for twenty or so years until her final collapse from whatever drugs or alcohol or “excitement” killed her.

The bus slowed, then pulled into a hotel’s drive, stopping at the door.

“Rest stop, and a restaurant for those who wish to dine!” the driver called out in French. “We will be picking up our tour guide here—Monsieur Alexandre Hippolyte Gascard, S.J., Professor of Assyriology from the Sorbonne.”

How could he not be excited with the things they would be seeing? Carol wondered, dumbfounded. Was the man a walking corpse? What archeologist’s spade had turned him up? He seemed a perfect match for Mrs. Grundy, and she mentioned this to Ron, who nodded but hardly noticed the man. “How could they pick such a prig as him?” she muttered to herself. What could they be thinking of at the travel agency? In any case, she was determined to enjoy herself.

“If anyone does not show up in time for departure, we will leave that person behind!” the professor admonished them. “We have a very strict schedule to keep, and with that said I won’t issue another warning! I am not accustomed to repeating myself! So be on time and keep together with the group, or be left behind! I’ve left people to walk back to Paris before, and I’ll do it again if you prove to be a laggard!”

Then he led them into the hotel like a rigid schoolmaster with his cowed, pasty-faced students.

Maybe she overdid it—turtle soup, crepes, escargot, truffles, etc., following but they weren’t finished with the whole meal when the professor rapped on their table in passing and they saw they had to leave immediately or complete the tour on foot!

Highly annoyed, since she was only half way through the ordered courses, Carol considered doing just that! So she didn’t scramble to get herself and Ron to the bus and finished their meal. When they reached the curb, it was already pulling away.

Ron woke up at the sight and began to run after it though without any chance of catching it.

He turned back to her, furious.

“Oh, let them go!” she laughed. “That gloomy guide they dug out of some Jesuit cemetery would have ruined the tour and made us perfectly miserable the whole time! Now we can see things ourselves the way they should be seen, without his views getting in the way or anybody telling us how we should look at things!”

Ron didn’t look so sure of it, and his Scandinavian moodiness began to drop on him.

Knowing the signs, she immediately swept up to him and kissed him. “It won’t be so bad if just the two of us go to Normandy, will it? Wouldn’t you like that better? Just us two?”

He softened in her Gypsy-like charm as he always did. “Okay,” he said, slowly, his blue eyes gazing deep into her dark eyes. “But how are we going to get there now? A cab? I suppose we could hire one, if we don’t run out of money to pay the fare. Maybe we could catch up with the bus. They headed somewhere here in Giverny.”

As if in promise of a good turn of fate, sunshine broke out of the clouds and lit the street brilliantly. Paris, promising light, couldn’t produce much, but the countryside more than made up for Paris. It was glorious on the outskirts of Giverny.

“Surely, he can’t miss Rouen!” Carol groused, then laughed at herself. Ron smiled, and together they looked forward to seeing the birthplace of the legendary maiden who saved free France from the English tyrant, King Henry the Third, or Fourth, or was it Sixth? One Henry was enough for France, anyway!

She was fascinated with the scenes. With a direct flight from New York to Paris, she hadn’t seen anything like this. It was a dream come true-—to be seeing France in all its glory.

How beautiful were the old farms, every building cared for, every fence painted, every stone set in stone walls with ivy to run along the top as if pleading to be painted! She couldn’t fault anything she saw—-it was more than she had hoped to see.

French farmers, and their wives, worked out in the fields without machinery, with various work animals and carts. That willow tree draped partly over a blue-painted gate.

The group of wine barrels with cats perched on top, sunning themselves. Fields of broccoli, leeks, onions, and various flowers for the Paris markets--it looked as if things had not changed for hundreds of years. Had war been fought in these parts? They looked so utterly peaceful--like Eden must have been like before Adam and Eve sinned. There was no sign whatsoever that all this had been a major battleground of World War II, where hundreds of thousands of men had clashed, along with thousands of planes, armored vehicles, tanks, and artillery.

“Why go so fast?” she protested in French.

The cabby smiled, speeding up still more.

It was growing so terrifying that Ron grew concerned, pulling his attention away from his book.

“He’s going to kill us all!” Carol said to him after a near collision with a loaded milk van. “How do we get him to slow down? He’s drunk and gone totally crazy!”

Burning rubber, the Mercedes Benz braked hard on the slippery cobblestones, and Carol and Ron were nearly thrown into the front seat.

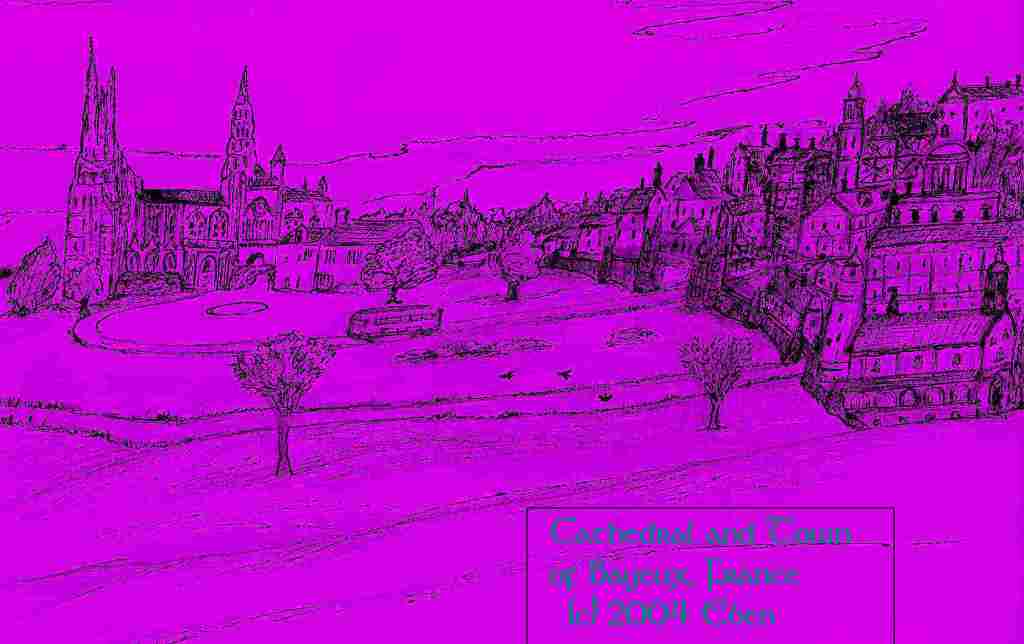

Right ahead of them was the Rouen Cathedral, and they had nearly driven into it!

Tumbling out, Carol and Ron scrambled to get clear of the cab while they still could.

The driver, smiling, relieved himself on the cathedral wall as they looked on dumbfounded by his impudence, then demanded an outrageous sum, but Carol took the money and thrust it into his hand, trying hard to remember that she was a Christian and keep some words from being said.

The cabby swung away from the curb, honking his horn, and Carol stood looking at him. “He probably does this to Americans, to pay us back for rescuing the French from the Nazis in World War II!”

Ron didn’t comment, which meant he probably agreed. But what where they to do? They were in Rouen, still in one piece, thank God!

“But what about our bags?” Ron said.

“Oh, no!” Carol moaned. Just then they remembered.

Down the street sped their bags in the back of the madman's cab.

Carol sank down on the curb. “All my paint supplies—-gone! I was going to paint Mont St. Miguel and the sea! Oh God, why does this have to happen to us? We had--”

She began to weep. She had brought her painting gear from the states, and couldn’t afford to replace it.

Ron pulled her to her feet. He smiled at her gamely. “We’ll buy some supplies for you here, if there is a shop. Don’t give up so easily.”

Carol didn’t recover this time so quickly. She let him lead her on, but her heart wasn’t in it. There wasn’t any chance they could find what she wanted, and at a reasonable price. They tried the markets and shops, with no luck. Flowers, postcards, TVs, auto parts, radios, furniture, portraits painted on the spot, fresh vegetables and fruits, antiques, various items of boudoir plumbing, clothes, leather goods, perfumes, chocolates, light fixtures-—but utterly no paint supplies.

They had to get out of the wet, so they went first into a restaurant for coffee, since it was too eary for dinner.

Carol sat, her elbows on the table, looking up into Ron’s face. “Well, got any plans? I think I have run out of steam!”

Ron, she knew, was content most anywhere, as long as he had a good book. But this was to be their romantic interlude. The extensive language studies were dull to the point of tears, and high-priced, inflationary Paris had been a struggle to survive in—this was their brief moment to enjoy, before they wound up their affairs in Paris, bought their mission supplies, and sailed to Africa to begin their six years of missionary service.

Ron said nothing, and she let the matter drop for the moment. They ordered coffee and pastry.

When they were half way through, Carol had an idea. Her face lost all its uncharacteristic sadness and she was beaming once again.

Ron scowled at first, but she kept bearing down on the fact their bags had been stolen, and he eventually came round to her thinking.

“They would insist they help us out in this emergency, dear!” she insisted. “They know what this outing means to us! Don’t make them out to be tightwads, for they’re far from that. Let’s not let the expense keep us from enjoying ourselves this last time. Dad’s business, the water company, is doing well, so they can easily afford whatever we put on the card. Well? Do you want to make them misers, or give them the chance to help us out when we truly need help?”

She was glad she had had her handbag, with the card in it, when she leaped of the cab. Otherwise, she knew, they would have lost it too. She normally hated carrying anything, but it was the most easy thing to stuff with sun glasses, gum, chocolate, etc., that she didn’t like to carry in her pockets.

She also knew something else she could do. Leaving the café, she dragged Ron back to the markets, and there, using the card, she bought a portrait artist’s entire paint set and gear.

Ron had to look away as she finished the negotiation. His face was red when he heard how much the man had charged them.

“Well, it was the only way to get what I need,” Carol explained, smiling. “Hey, wipe that frown away. You’re not paying for it!”

He had to chuckle at that, and humor restored, they turned toward the next task. Where would they get a car?

“We want to drive ourselves there,” they explained to the group of cabbies. The men shook their beret-topped heads, as if they hadn’t heard of such a thing before.

Carol knew they were just holding out for more money. “We want to rent a car for several days! We will return it here! How much?”

After considerable squabbles, one man stepped forward as if he had been appointed their representative. “Five thousand francs a day, not including petrol,” he said.

Carol’s face fell. She turned to Ron. “They’re absolute thieves. That’s about 100 bucks a day, in our money! I think I’d rather walk to Normandy than pay them that!”

Ron agreed, and they started walking away. They had gone half-way down the street when the cabbies were running to catch them.

Minutes later, after showing their identification and paying in advance for a week, they were on their way.

Handling the vehicle, which was a British car with the steering wheel on the right side, was a challenge for Ron.

He managed to get them out of the medieval district of Rouen without a mishap, and Carol, settling back in the seat beside him, began to think there was going to be a romantic interlude after all.

Just a mile or so from town the car sputtered and stopped in the road.

Ron checked the tank. “No!” he cried. “They let us go without any gas! I wouldn’t doubt if there’s no oil or water in it either!”

Carol clapped her hands over her face. “Oh, Lord! Oh, Lord!”

“I’ll go to the nearest farm house and see if I can buy some gas,” Ron said, standing in the drenching rain.

“I’m going too! You’re not leaving me alone with a million French donkeys, are you?”

They pushed the car over to the side, locked it up, then hurried to find the closest farmstead.

Spotting a lane leaving the road, Carol instinctively pulled Ron’s arm, and they tried it. Slipping in mud, stepping in puddles, they followed the lane through dense hedgerows, and suddenly it opened up on a farmyard. A couple old trucks, looking like vintage World War I army vehicles, and a barn and attached house stood in big sheets of standing water. Wading through, they reached the door, a porch that ran all along the side, and knocked. The moment they knocked, it sounded like a pack of wild dogs threw themselves on the other side.

Then they heard a woman’s high voice, and the howling and snarling fell instantly silent.

Carol and Ron were astonished. The woman of the house was an old woman, with long silvery-grey, braided hair falling down nearly to her waist, dressed in silk pantaloons and a deep-cut silk blouse that left nothing much to be imagined.

“Come in! Come in, my dears!” she called, forgetting the jam and crooning to her goats at the same time. Trying to push through the curious goats was difficult, but Carol and Ron persisted and got into the house. Fortunately, the pet goats and dogs were kept out on the porch, and they found themselves alone with the lady in her kitchen.

Stone floors, plastered walls, an antique lantern-like light fixure of pewter, a huge iron range, a butter churn, everything looked as if it had come out of the 19th century or an even earlier age.

The lady introduced herself, smiling sweetly at Carol, and winking at Ron. “It is wonderful to have a man in my kitchen,” she began, talking to Ron first. “I’m afraid an old lady might say or do something she might later regret. But there haven’t been anyone like you here for—for—“ Her eyes misted. She seemed to forget what she was saying as she turned back to them.

“I so adore to have such young people in my house! You are lovers eloping from your parents’ control, oui?”

Carol glanced at Ron to catch his reaction, laughed at his expression, and decided it best to go along with this most charming Frenchwoman. Had she been an important somebody’s mistress in “better days”? No doubt she had quite some stories to tell.

“Yes, we are newlyweds, “ Carol replied. “We are on our second honeymoon—really our first—since we didn’t have the money to do much on the first.”

“Married? Married? Well, well, that isn’t the worst thing in the world that could happen! And you are in the right country, where we know how to fix things like that so that everybody can be happy. But you must stay with me! I will fix dinner for you, and you two will eat it alone—I do not dine with other people anyway. I will give you my dear Hippolyte’s—-or was it Jules’?-—favorite room in the house—for I never use it since—since—oh dear--“ She seemed to lose her train of thought again. They waited, and sure enough, she saw them again, recollected where she was, and they were off on the right track once more.

Carol explained, since her French was much better than Ron’s, having started hers in college. “Madame, we ran out of gas. And it is a hired car. A cabby took our bags, so we have just what we are carrying. I hope we will be no trouble to you. We can pay for any expense we cause you. We will need gas for the car so we can get on our way to—“

At the mention of their going so soon, the goat-lady frowned and pouted. “No, no, no!” she cried. “You cannot go now!” She pushed them both out of the room, and they found themselves propelled into another room, which turned out to be an antique bathroom. “Take off your wet things-—everything! I have robes for you, slippers, stockings, and men and ladies’ lingerie—“ She winked at Ron and Carol, and they had to laugh. It was the most antique sort of wink they had ever witnessed. It was done so elaborately, it might have been done in the Sun King’s parlor by some aristocratic lady of court.

“You could do the dancing well enough,” she observed, scrutinizing Ron’s legs and torso. “You look—ah, a good match for a good woman.“ Then she hurried out.

Ron bustled into his robe as Carol laughed at his expense. “She did that on purpose!”

When they were ready, wearing robes, slippers, and whatever else she found for them, they were conducted out into the parlor, which was a well-to-do, gentleman farmer’s—circa 1840. It was chilling and damp as a French penal colony cell in there, but their hostess soon got a warm fire going in the antique stove. Carol was leafing through some albums of musical comedies, and was trying to place their hostess in one of the can can chorus lines. Their hostess came in and saw what she had, and laughed. She went to the piano, strummed a bit of a music hall tune, got up, took a few steps, arched her neck and wriggled a bit, singing a few bars in an old lady's quivering treble before she seemed to remember her dinner on the stove and hurried out, cursing in street market French.

Carol agreed. “Yes, it is very quaint, just like her. But she means well. So why not? Do you want to go back out in that?—“ They heard the rain beating on the roof.

Ron shivered. “Well, she’s got all our clothes, doesn't she? So how can we go? It must be a trick she plays on her guests. This way they are captive audiences until Madame Lonelyheart tires of them and shows them the door!”

She didn’t seem to hear as Carol tried to explain that they didn’t drink alcoholic beverages, except a ltitle wine now and then, and that they were missionaries.

Their champagne poured in cupid-decorated goblets and given to them, their hostess vanished back into the kitchen. She swept back in for a moment, put on a record of Debussy's "The Sunken Cathedral," and departed.

She returned with a gaudy gold, over-ornamented candlelabra, all lit, and set it down on the table. It should have been tasteless French decadence, but it didn’t have that effect at all.

The room was now strangely beautiful and enchanting, in the candlelight. The golden sheen on the candlelabra, the gilt frames on the family pictures, the delicate Breton laces, the velvets and tassels of the curtains, the ornate dark furniture, the leopard skin spread on the Persian carpet—-it was a classic scene out of Sarah Bernhardt’s heyday, when she was playing the lead in "La Dame aux Camelias."

Very hungry, Carol tried it, and it was delicious.

When they finished this, a thin vegetable clear soup with an artistic swirl of plum sauce arrived. Then followed course after course, each one more elaborate.

The food was wonderful in taste, even if the selection based on her farm produce was a bit quixotic, and each plate was as elegant as the best in Paris.

“Superb!” Carol muttered to Ron, who was saying nothing but eating everything set before him. Comfortable, warm, attended to by an excellent cook, he wasn’t protesting in the least.

Dessert came at the last, which was simply wild strawberries, sliced in a decorative way with a light cream sauce of some kind sprinkled on it instead of heavy clotted Danish cream that was so popular in European capitals. They couldn’t have handled anything the least bit heavy at that moment. This was just perfect.

As they finished their dinner, they heard their hostess going up the stairs. She seemed to be moving furniture over their heads. Then she reappeared, and with smiles ushered them to their bedroom. She beamed at them as she threw open the door.

“I thought you said it was your late husband’s favorite room?” Carol said. “Philippe, did you say that was his name?”

The goat-lady laughed. “My husband?” she said, as if she had forgotten. “ Oh! Yes, dear, dear Philippe! No, you are wrong. It was Etienne-Louis! My darling preferred this color. He wanted me to feel more at home in his room!”

Carol frowned. “You aren’t giving up your boudoir for us, are you? I wouldn’t think of taking yours from you and invading your privacy. We can go stay at a hotel tonight!”

The lady looked shocked. “Oh, no! This is all yours! Feel at home! Stay here as long as you wish! Please! It doesn’t cost me a franc. My poor departed husband, my divine Leon, would be very displeased if you left! Please stay!”

Carol almost felt like the lady would be hurt if they didn’t accept. She nodded. “It’s very very beautiful.” She went over to the canopied bed. “I’ve never slept in a bed like this before. I'd feel like Marie Antoinette and wouldn't be able to sleep, thinking of the guillotine.!”

She then swept out, leaving them alone.

Carol looked over at Ron. The room was lit with candles. The stove was lit. A bottle of champagne, with chocolate eclairs and more prophylactics tied with a pink bow on the pillow—-what hadn’t she thought of?

Ron went over to the bed and sat down. He looked over to her, and that was all that she needed.

If only she could paint her! She was an absolute original. But there was no time. They both felt they needed to be on their way. Perhaps on their return, they could stop by and get a portrait done, if the goat-lady would agree to it.

Reacting the same as she had at the Minneapolis showing of Hiroshima Mon Amour, she bawled like a baby.

Ron nudged her. "What do you see that I see, and hear that I hear?" She thought he was making fun of her at first. "Graves, you mean? Countless lives cut short for the sake of our freedom?" she answered without really looking.

Ron did not say any more. He simply pointed. Carol then saw what he was trying to get her to see--if only she could open her eyes to see it. The patterns of light and shadow--ever changing as the wind blew the grasses and the branches of trees, were playing across the sea of graves.

Then, hearing the whispering sighs of the wind, she heard it too. It was like the slightest echo of a grand symphony, and the music was better than any human composer could have created.

For long moments afterwards, when they were driving to Bayeux, they couldn’t find any words to describe what both felt.

“I just hope they lived long enough to love and be loved, before-—before-—they were slaughtered,“ was all Carol could get out.

Ron nodded gravely as a young man would when contemplating death and kept driving through the misting rain.

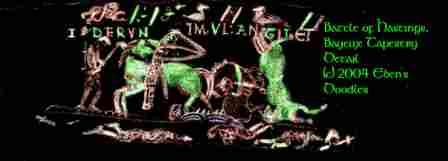

She turned back to the inscriptions. “From the abrupt ending, some panels are perhaps missing, and they don’t know what they were portraying. It would be interesting to know! My guess is that it was probably the best part, but too controversial for the old bishop, and he had it torn off before the tapestry was displayed publicly in the cathedral! ”

“What about the Qumran scrolls of the books of the Bible, found by some Bedouin goatherds in the Israeli desert after being lost for two thousand years?”

“You have a point,” Ron laughed. “But this isn’t desert country. It’s much too damp to preserve old things like cloth or paper from even a hundred years ago.”

“Well!” she retorted. “This much of the tapestry survived 600 years of fire, wars, and invasions, did it not? Why shouldn’t the missing portion survive the same way? They must have known about the dampness back then to do something about it. Were they that stupid to not to have thought of a way around the problem? And I thought you were the logical one!”

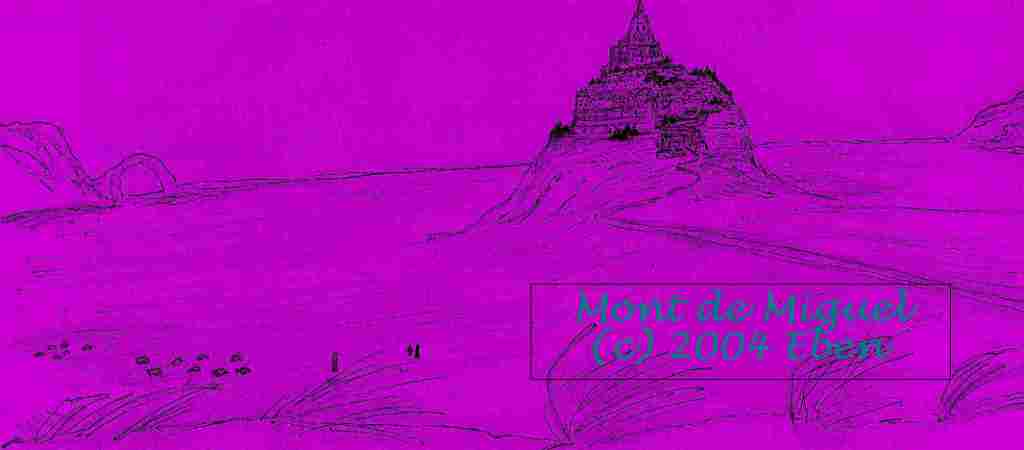

They left the museum, intending to reach Mont le Michel before the tide came in. They had several hours to do it. After that, the tide would keep them cut off from the Mount and the abbey until the following morning.

Carol turned to Ron as he drove toward the most beautifully-sited abbey in France--—one of the world’s most spectacular architectural masterpieces, as every travel authority agreed.

His mind on other things than the scenery, he didn’t say anything, as he was always sparing on obvious words.

She kissed him. “Well, I’m liking it too. Very much, in fact!”

They reached the road leading across the vast grasslands of the salt marshes to the abbey in the distance. She pulled up, for the sight of it was staggering, beyond the capacity of the various descriptions and pictures of it they had seen and heard.

It could hardly be believed—-all that ancient maze of buildings dedicated to Michael the Warrior Archangel stacked on a steep-sided, 400 foot high mountain, with the sea in the distance, and all around the salt marshes and mud flats.

It was hard, once they got across the salt marsh causeway, to find a place to park. The Mount had a lot of tourists to accommodate, and parking space was extremely limited. They tried first one spot and then another in the tiny village that clustered beneath the abbey that crowned the summit of the mount. Each time they parked, someone came out from a shop or restaurant and motioned them away.

“What are we going to do if they don’t let us get out of this car?” Carol cried.

On the verge of tears, Carol was relieved. “Yes, we’ll stay here then! Well, I’m glad that’s settled.”

They climbed the stairs to the ground floor. The concierge was at the desk. They took a room, paying with the card. The concierge gave them advice as to the better places to eat. Your bags? They were asked.

“All stolen,” they told her. “We don’t have anything but what you see we are wearing.” The concierge looked shocked and offended, but after they started to explain what had happened in Rouen she interrupted them, handed them the room key and said if there was anything they wanted, she would see to it they got it. “I trust you don’t judge all my countrymen by his terrible actions!” she said, pointing out an aged, crumpled U.S. flag draped on a wall next to the French tricolor. “If it were not for the Americans—well-—the execrable Nazis might still be in charge of civilization! My husband and I were in the Resistance, fighting both the Vichy and the Nazis, but—ah!--so many, many of my friends and family were executed whenever we shoot a bad Nazi—one hundred of us had to die for one of them, the monsters! I can never forgive them—-that is why no Germans ever stay here! I send them out immediately even if I have all empty rooms!”

The concierge looked as if a donkey had made a rude noise. “Forgive the Nazis?” She began to laugh. “You can forgive the Nazis? But you didn’t know any! WE KNEW the Nazis! When you know a Nazi, and he kills your family and rapes even the little girls as their parents are forced to watch, then come and tell me I should forgive them!”

Carol was shaking her head listening to this, but she let it go.

When they went up to their suite, the concierge sent her daughter, a young girl with some things for the lady—toiletries, a fashion house-designed chemise, and dainty feminine things she might want for the night, along with a beautiful robe. Former hotel guests had left very nice things by mistake and no doubt wouldn’t come to retrieve, the girl explained. Carol smiled and told her to thank her mother.

But she might not have said anything, for when they returned after dinner they found everything a young man might want laid out on the bed. It was superb—the best French wear, Pierre Cardin robe, pajamas, underwear, stockings, and even several ties and a pair of dress pants. Besides this, there was a box of chocolate eclairs from Maxims, and a bucket with champagne, not to mention bouquets of carnations.

“I wonder what we’re paying for all this!” he murmured, aghast.

Carol shrugged. “Calm down! Remember, this is daddy’s gift! Mom, you know, is full-blood Yakima Indian, and as sharp as her people can be, she must have foreseen there’d come a time we’d need the card and got him to give it to us.”

As soon as she was ready for bed, she found Ron sitting up with his Barth, his eyes fixed on the dense print.

He seemed so distracted, however, that she decided they had to have a little talk. “What is bothering you? Cmon, tell me. What is so interesting in your book anyway, that is better than this time away from Paris, and just the two of us to enjoy it?”

He murmured a few words, but she wasn’t buying his explanation.

She put her fingers on his lips. “Stop it! I want the truth! What is going on with you—and us! You are beginning to concern me!”

This seemed to sober him, and he appeared to consider his words most thoughtfully.

Carol looked at him with a stunned expression for some long moments.

“But you know that isn’t true!” she finally protested. “I don't care who objects or imagines it didn't happen as the Bible reports, the truth is that God Himself bridged the gulf between Himself and mankind. He became man in Jesus Christ! We believe that as Christians! That was the whole point of the miracle of the Incarnation—we could never reach him, granted, so He came down and reached us in Jesus! Only that way could God could be touched, heard, spoken to, hurt, even killed for our sake! Barth doesn’t accept any of that, does he? It is only some kind of show or appearance or symbolical gesture. In other words, God still was God, and man remained man! Never the twain shall meet, right? How can He be a Christian and hold such views? There would be no point to life, to speaking about Christ, if I believed that tripe!”

The conversation at that point seemed to be going nowhere, so she let it drop. It wasn’t a good practice to get the best of your man intellectually, she thought. She tried to be casual about about her objection, while telling him her position. “I wish you wouldn’t read him anymore,” she said, turning out the light. “I have a feeling that it is getting to be more important than our faith in God, the mission we’re called to, and it’s grown more important than—than us. You care about us, don’t you? Of course you do!”

An hour later he went out of the room, and later she got up to go to the bathroom and found him reading in the bathroom.

“What?’ she cried, struggling to awaken herself. “Don’t tell me!” She glanced at his book. “What is it? A drug you’ve got to have?”

He gave her that thousand-miles-away. abstract, intellectual look he often had lately. “I know you don’t like it, but to do him justice I have got to finish his book before I can make up my mind, fairly and objectively.”

“Okay!” she retorted, her last shred of control gone. “But I really don’t think it is doing you—us—any good! I wish you would—throw it out the window before I--”

They could hear the waves now slapping at the mount’s base, for the sea had returned to all side of le Mont St. Michel.

Putting the detested thing away, she decided to wait until a better time presented itself.

After that they could take a leisurely drive back to Paris via Tours, afterwards stopping to see the various chateaux in the Loire Valley and their famous gardens to make up for Monet’s gardens at Giverny which they had missed, thanks to the rascally taxi driver.

After a Continental breakfast, they left the hotel for their walk as soon as the tide was out. The salt marsh grasses were wet, and little pools of water stood there and there, yet the ground was firm, thanks to the thick roots of the grasses. They had walked about a mile toward the southwest when they saw sheep.

“Sheep way out here?” Carol cried. They had to investigate.

“Why not?” he laughed. “Here I can usually get away from everything modern and decadent—-until the tourists come in the tourist season, that is!”

“Oh!” Carol burst out. “I am afraid we are disturbing you then!”

“Not at all. You see, I sometimes find it a bit lonely out here, with days and even weeks going by before I see anyone. Sheep have a problem relating with shepherds, you see. They’re like babies which never really grow up. So I am always ‘daddy’ to them, and that can be a constraint to communication!“

Then he paused, extending a hand that engulfed each of theirs in turn. “Jean-Baptiste Banqui,” he said. They exchanged their names, and he had them put their names in a small black address book, after explaining that his memory was failing.

“But where do you camp? Do you have a tent somewhere?” said Ron in an odd manner of an adult speaking down to a child, looking doubtfully round the vast marshes.

Carol darted an annoyed glance at him when he said that, taking a cue that Ron was humoring the old man, while thinking him a bit mad.

“Oh, no,” the shepherd-scholar replied forth-rightly, ignoring the tone Ron was using. “I have to go with my sheep up to higher ground on the mainland, before the tide from the bay returns. Would you please honor me by being my guests? And I can show you some strange artifacts from ancient times, statuary in fact, that the tidal waters cover most of the time and most people know nothing about, since the tall grasses hide them even during the day when the tide is out. Well, monsieur?”

Shifting uncomfortably on his feet, Ron looked at Carol, but Carol nodded eagerly.

“Yes, we’d be happy to visit your camp!” Carol told him. "And I'd love to see the ancient statues."

The shepherd then blew a whistle, and an unkempt sheepdog they hadn’t seen out on the marshes came bounding toward them. With another sign from the shepherd, the dog went to work, and began to move the scattered flock back toward the mainland.

“But they haven’t finished eating!” Carol said.

“Oh, they can still eat all they like, as they walk long. You’ll see.”

It was as he said. Despite the dog’s best efforts, the flock wasn’t going anywhere fast. It was slow going as the sheep made their way back, most pausing to eat a little here and there of the luxuriant, waist-tall marsh grasses. It took considerable time to make progress enough to reach the site of the ancient statuary.

“Ron’s afraid our concierge will think we’ve perished,” Carol said after a while. “Maybe we should try to get back before the tide.”

A squall was sweeping in from the sea at that moment, and with it came flying sand and the strong tang of salt—an unmistakable sign the tide was coming back in somewhat early.

Carol glanced back at the Mount, and the incredible sight of the still living, breathing Middle Ages, standing fully intact and impregnable, in the midst of the salt marshes of the coast, made her shiver. It was no longer the majesty and beauty that attracted her, nor its massive show of strength and endurance. Rather, the sea that was sweeping in, its waves were the real ruler of the coastlands—and that meant change would come even to the Mount-—eventually it too would be worn down by the waves and ground into sand on the seashore. It was only a matter of time, a very short space of time in a geological time frame.

As she walked along she couldn’t help comparing. The gentle octogenarian giant and her own much shorter, slighter-framed husband. A sudden insight startled her. She saw what was being revealed to her in formerly vague ways was now being sharpened in clearly defined outlines. It was more felt than intellectualized but, nevertheless, just as true as anything a logician could formulate. But how can I confront him without making him defensive? She wondered.

A great urge to shout at him—-to turn back, to turn back, before the sea swept over and drowned him—-that gripped her and she was hard put to resist, but she decided to let it pass-—and the moment of danger was over. Limply, she trudged along, her options seemingly exhausted. Would she have to let Ron go without a struggle? If she tried any strong armed tactic, she knew it wouldn’t work—but if she did nothing, was that any better?

She felt like waves of tears were sweeping over her soul. Tears for Ron! She was seeing him being swept away and drowned before her eyes. Barth, the old godless, lying monster, had won! Christ-—and Michael the Archangel with Him--had lost.

Why did he live in a primitive tent when he could live in something more substantial? Carol wondered, and she could tell Ron was thinking the same thing as they watched their host first gather his sheep into wattle-sided pen for the night and pour them some water in a trough that looked so ancient it might have once done royal service in Bethlehem.

Ron looked like he might want to refuse, but Carol gave him a look and he gritted his teeth. “Alright,” he said to her in a whisper as they waited. “But I am not promising we will stay.”

They stepped in when their host called.

The moment they did so Carol gasped. Sevres porcelains? Persian carpets? Bookcases of rare books. A chess set with ivory pieces and marble gameboard. A Korean celadon vase (mishima), Koryo dynasty, 13th Century, holding a dried wildflower arrangement. Except for the reprint of Rudolfe Bresdin’s “The Good Samaritan,” it was the exquisite domicile of a dilettante sultan transported to the 20th Century!

“Do you like it?” the shepherd chuckled. “Now you know why the car and boat occupy the army huts. Mechanical things can’t suffer from modernity. We will be more comfortable here, and we get to hear the sounds of the sea waves, without the sound of a metal walls being hammered by rain.”

Their host, after giving them Algerian-made, Berber design cushions to make themselves more comfortable, got them blankets to lay round their legs for warmth.

“It isn’t that cold now, but there is still some chill at nights. I didn’t feel it when I was younger, but I guess it is the damp. Anyway, I can always pipe in heat from a gas furnace and generator outside in the army hut if it really gets cold.”

“Have you decided?” he asked as he poured them each a glass of wine. He handed them menus. “I’ll call first and later pick up dinner for you at the hotel. Which do you prefer? Sea food? Meat dishes? Truffles? I know you Americans mostly like beef steaks done rare. They have those too, for a lot of Americans and Britons and Australians pass by here and would think they’re starving if they weren’t served steak.”

The shepherd entered the tent, glancing at them expectantly.

“We’re be happy to accept your invitation!” Carol said. “If you want us to stay, where would you put us up? Here?”

Their host laughed. “No, not here. I have no regular bathing and bathroom facilities to offer you. My dog, my little sheep, and their old keeper live rather primitively, and prefer it so. But I wouldn’t think to subject my guests to the lack of amenities. So this is fit only for misanthropic bachelors and recluses! I will drive you to the village and you can have nice clean rooms at the hotel with a private bath, which I hire year-round for me and my guests from Paris and abroad.”

“Guests?” Carol wondered aloud. She looked around. There was no sign he did much entertaining in the tent.

She crawled over to the bookcase, and began to look at the titles. Camus, Sartre, Heidegger, and other leading existentialists.

“You shouldn’t be going through his things,” Ron said as he began to pull out the books and look inside each cover.

“Oh, hush!” she said. “Just look at this! You’ll never believe it unless you see it”

Ron’s eyes widened. Each book was autographed for their host! And they were First Editions, which meant they were worth a small fortune each!

“Now do you want to leave?” Carol taunted him, knowing he had dreamed of such encounters as this with a great mind, but had no way to bring it about.

Ron shook his head slowly. His look of astonishment and even awe was something she would never forget.

Carol, relishing the exotic Arabian Nights decor, let them talk without interruption.

Ron’s questions, she noted, turned from being general at the beginning to more and more a narrowing focus on the relation of Existentialism to modern Christian theology. To her it seemed he was throwing at their obviously learned host a line of questioning not so much about the existence but the possibility of communication and even the linguistic problems relating to Christianity’s God. He was asking this strange man they had met by chance earlier that day how existential “alienated man” could apprehend an infinite God with his finite mind and spirit.

“Rudolf Bultmann, in his excellent Kerygma and Jesus Christ and other books has set ground rules for the discussion for this question for most of us, as you probably know,” observed Ron in his soft-pitched, precise voice that their host had to bend close to hear. “I really can’t see how anyone can do better than he did, showing so clearly as he has that there really isn’t a Incarnation, nice as the idea is for bridging the gulf between God and man.”

Carol, hardly knowing if she should leave in disgust, or stay to see what came of it, decided to hang in for the results, though it took extreme self-control to sit there while the fate of her marriage and the fate of their mission was being decided right before her.

“If he really doesn’t believe in Christ in his heart, I’ll never go to Africa with him!” she resolved, tears glistening in her eyes, as she fought down the fury rising within. “I leave him right here on the beach!” She gazed at them both, wondering what terrible fate was in store for them. Would their marriage end that night too? She couldn’t bear living with the likes of Barth and Bultmann, two black-robed angels of disbelief and hypocritical Biblical scholarship, the rest of her life. Were they part of her marriage vows?

To her Christ had to be a true, living Person, or nothing at all to her. Faith was a simple matter of a trusting relationship, and God honored faith, by showing those who believed in Him things reason could never see and grasp--like heaven, like the beauty and mystery of life, like promised things only God could do, and so on.

It was a living relationship, lover to lover, friend with friend! You related, person to Person with Christ-—you didn’t ever call Him a myth or a symbol of something and then proclaim the goodness of that mythical Person while denying His life and connection in time and space to human beings.

What an ultimate insult, treating so intensely personal a God that way!

Yet that was what Barth and Bultmann and their de-mythologizing school of theology were doing!

To her mind they had bowed to existential philosophy and thrown out the heart and soul of Christian belief, while holding to the trappings of the doctrines! They were actually denying the whole reason for the Incarnation and claiming it was valueless, of no real significance. To their thinking, God did not become man in any real way. As human beings she and Ron and every other human being could not claim Christ as a fellow human!

All this she was seeing clearly, yet how could she express it to Ron. He would refuse to hear her arguments in favor of a reachable, living, personal Christ—since she couldn’t put her arguments in the precise theological language he demanded.

She wondered what she might have missed, but it was growing late. “Could you drive us back, Monsieur? You’ve been so kind to give us dinner, but I prefer to sleep on the Mount tonight.”

“Of course!” their host replied quickly, putting his books away that he had pulled out to show Ron one passage after another. “I’m sorry I’ve been so windy. I’m afraid all this philosophizing has been boring to you. But I felt it was important to carry the ideas of the great teachers to their ending conclusions. When a man goes to the end of a thing, only then can he see it for what it truly is—oui? So I am sorry I bored you terribly with this kind of discussion!”

Their host checked his watch. “We have fifteen minutes exactly. I know the tides. This one, with the wind, means higher waters than usual, but we should be able to make it across. I’ve done it many times before. If I have to, I’ll stay on the Mount tonight.”

“Are you sure that won’t be trouble for you?”

He laughed. “Not at all! Remember, returning you to the Mount was part of the agreement in getting you here for dinner. I’ve enjoyed our time together immensely. But we must go at once.”

They hurried out to the car and in a few moments he had it running. They then discovered how such a large man could find space for his long limbs. He had modified it, so that his seat was actually pushed to the back seat, and both Ron and Carol sat in seats alongside of him. The moment they were all seated they were off through the dunes.

It seemed too late to try to get to the Mount before the waves cut off it off from the mainland, but their car kept flying along the edge of the waves, with spray hitting their windshield.

It seemed to Carol it was clearly too late and they should turn back. The whole area around the Mount was under water, she could see as they neared the road that led across the cordgrassed marshes.

Their driver, pausing a moment, then swung the wheel and dove right into the water at a point where it seemed they would be drowned for sure. Carol gasped where she sat in the back seat. She saw Ron in the passenger seat gripping the dashboard with blanched knuckles as if that would do any good.

Sheer horror kept her from crying for help. Their driver didn’t seem to notice anything particularly alarming, and kept plowing through the water toward the Mount which seemed impossibly far to reach.

“I’ve got a rope—-grab and hold it—-and I’ll go ahead from this point.”

What else could they do but act as they were told? The moment they grabbed it he pulled and off they went as he plunged through the water like a thoroughbred horse. In another minute he the water was down around their calves, then they were stepping out of it altogether. But the tide as sweeping at them with greater waves than before, and they hurried up the sloping road just ahead of its crests.

Gasping for breath, Carol and Ron high enough to see they were safe, and they looked back to thank their rescuer, but he was gone. Carol screamed. They saw him heading back into the water with leaping strides that belonged more to a centaur than to a human being.

But though they fully expected him to perish before their eyes he came surging back toward them, the aged Citroen in tow. The car was safely on the higher ground with them when he stopped to rest after pulling the brake and tying the car to strong piers of an ancient dock that once stood there and landed drunken, celebrating, Normans returning home from England’s conquest.

“It’s been through higher water than this many times before,” he told them, stomping to get some of the water out of his shoes. “I’ll get it running again tomorrow after a good, little flush of her pipes. Don’t worry about any damage to it. I’ve modified it to take the salty baths she gets here. You’ll see!”

She soon found out, as they stepped in sodden shoes into the hotel lobby. The moment the concierge came out of her room to greet them she started laughing.

“Oh, no! Not again!” she cried, in French. “You poor, poor dears! I hope you don’t catch colds for this abominable treatment of Monsieur Blanqui’s!” Tiny though she was, she shook her finger up at the giant, and he looked as if he were a small, abashed schoolboy being admonished by a school-mistress of the 19th Century.

She led the way to their rooms, gathering more towels and clothes for them on the way at the head of the stairs, since the elevator was shut off after 4 pm for lack of current.

She pushed the giant man-horse into a room, handed him one stack of towels, and told him in French that a robe would be coming soon. Turning back to Ron and Carol, she saw personally to their needs by drawing a hot bath, then left them to go below for onion and cheese soup and some heated wine to help bring their body temperatures up to normal.

A typically unblushing French concierge, she seemed not to notice Ron’s embarrassment. “That nasty old beast Blanqui!” the concierge observed dryly. “He’s always trying to drown my guests! He has almost succeeded with several of them-—a very fine couple, a British Viscount and Viscountess, the Bracegirdles-—two weeks ago. I thought we’d never get her revived! Poor darling, she was just too delicate to come out of the shock quickly.”

Carol, feeling life come back into her limbs, sighed with relief as she sipped her heated wine. “That’s all right,” she murmured. “We enjoyed the dinner and conversation, not to mention a tour of the tidal marsh. I think we’re not going to be the same after this. Yes, indeed!”

The concierge darted a puzzled glance at Carol, but Carol’s eyes were closed, as she leaned her head back on Ron’s hairy chest.

Later, the concierge departed, Carol was the first out of the tub, and she pulled her robe around her and went into the bedroom. It was, she knew, the perfect moment as her eye fell upon the volume of Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics, eyeing it the same as it were a very angry, coiled black African cobra in their bed.

A few minutes later Ron stumbled into the room, his face carnation-pink as his whole body was pink from the hot bath water. He went over to the huge book lying on their bed like a hole of blackness and finality that had nearly sucked all his faith into bottomless oblivion. He stared down at it fixedly as if hypnotized by it.

“Are you going to do it, or do you want me to?” Carol said quietly, and at the sound of her voice he jerked and seemed to awaken to the real world.

Without a word Ron unlatched the window, and sea breezes swept freely in taking the curtains out of the room as they exited.

With a heave the heavy tome dropped like a black stone through hundreds of feet of space as it fell toward the distant waves below. They must have both imagined it-—or did they really hear it? Simultaneously, they waited for the impact and thought they heard the sound of one very solid object strike the water.

“Hallelujah, we're free at last!” was all Carol could think to add as she felt his hands and arms take hold of her.

Without a word despite the inquiring glance and questions, Carol smiled at her, shrugged, and turned to the elevator.

She left the elevator on their floor and went in to see how Ron was doing. “That was close,” she thought as she found him dressing. She handed him his Pierre Cardin Cupid-decorated silk briefs, then took them back and lay down on the bed.

She looked up at him shyly as he climbed beside her and started stroking her cheek. “Hey, let’s forget going down for breakfast and have it in our rooms instead,” she whispered, giving his shorts a fling.

“Good idea?” he replied. “I can think of something better we can do right here.”

So the lovers did what lovers do, utterly unmindful of the eternal verities, that would someday, long after Africa, snatch their life stories and set them far, far out amidst the stars a million years hence!

Faith of our fathers! We will strive To win all nations unto thee, And through the truth that comes from God Mankind shall then be truly free.

Faith of our fathers! We will love Both friend and foe in all our strife: And preach thee too as love knows how, By kindly words and virtuous life.

Faith of our fathers, holy faith We will be true to thee to death! We will be true, we will be true, We will be true to thee to death!

“Why are you looking at me that way?” she cried, steadying the wheel with one hand. She could see his thoughts even before they were spoken sometimes, but this time they came with a whole avalanche of emotion, as if his entire being had been swept by a giant wave.

That made them both sit silent the rest of the way into Tours. The World War II battlefields and cemeteries of the Normandy beaches, Joan of Arc’s Rouen, St. Michael the fighting archangel’s church on the Mount St. Michael, their rescue from the sea by their strange friend the shepherd-scholar, Charles Martel’s battlefield at Tours, then the shared song. What could Almighty God be telling them? What did He have in mind for them in Africa when they got off the boat at Douala, the port for the capital of Yaounde?