Another lineage feed the crow,

Another Argo’s painted prow

Drive to a flashier bauble yet.

The Roman Empire stood up palled:

It dropped the reins of peace and war

When that fierce virgin and her Star

Out of the fabulous darkness called... --W.B. Yeats

What wiseman before these times, or what sybil inhaling hallucinatory vapors from volcanic vents, could have prophesied this turn of events, from supreme earthly power to the Crucified One with the pierced hands and feet?

Jewish prophets had proclaimed it in ages past--but only Josephus, the general-errant of the Jews turned philosopher-apologist for the Jews, was reading the wider public with the whole account of the Covenanting God of Israel. Rather, not from the top at all, not from the exalted public squares and magnificent palaces and temples and schools of philosophy where new imported religions plied their wares to an informed, wealthy clientele, no, Christianity was a rose springing from the lowest depths of society, but from the steamy cloaca of the Roman sewers and the backways of cities where men crept to commit shameful deeds, even from the catacombs of the Dead, rose a Hand that now gripped the entire Roman world--a Hand that held even the imperial throne in its grasp.

The shamed, executed, rejected Yeshua claimant Messiah of the Jews was reaching out from his empty tomb through his ever-growing number of followers to gather in the whole world, starting with Rome’s dominion.

For Christians who knew of Diocletius, for example, it seemed peace for Christianity was assured, since the new emperor was known to favor the Christian religion.

For two years Christians breathed easier in the Empire of Rome. For twelve years now they had known peace, in fact, ever since the persecuting Emperor Aurelian was put to death by his own domestics in his palace in Constantinople.

Then in 286 imperial couriers raced to the chief cities and their officials with news Diocletius had appointed a second emperor, a co-Augustus, to reign with him on Rome’s capacious throne. Diocletius would rule the western provinces of Britain, Germany, Spain and Gaul, Italia, and Rome’s fatherland of Latium , and Maximian would be absolute sovereign in the fabulous East. Celebration was decreed in the eastern provinces, and the chief cities prepared to do the new co-emperor due honors when he came on a triumphal tour of his realm.

Everyone knew an emperor was coming, but what sort of man was he really? They had all been given ample pause to wonder. They all knew mighty Rome had already produced a notable line of monsters beyond belief--Nero and Caligula surpassing them all in unspeakable beastliness and insanity. There had been several that could be considered good, patriotic, well-meaning men, too--even a stoical philosopher with lofty thoughts whose only fault, from the Christian point of view, was that he persecuted them bitterly.

What was this new one going to be?

It was anyone’s guess, since the highest imperial office had a way of changing formerly good, sane men into Neros and Caligulas that no one could have foreseen in their worst imaginings. Perhaps the chief shortcoming in such instances is that the men were weak as all men are weak, and the imperial throne’s uncanny ability, due to so much power concentrated in one spot, was to subvert frail human nature to the point where it became pure poison to whomever was foolish or unlucky enough to sit upon it, warping his ordinary, flawed human nature beyond the point of recall or redemption.

“Where are your chief nobles and leading citizens?” the emperor queried his hosts, who appeared embarrassed and made lame excuses. “You here are loyal enough worshipers of Rome’s gods, but where are the others who are supposed to be here to greet me and kiss my feet?”

Effronted, Maximian was determined to get at the root cause of what he took to be aversion to him among the ruling classes. And not only the upper classes were involved in conspicuous absention from the festivities--huge masses of the poor stayed away from the triumphal processions down the main avenues of the cities. Those who did line the streets made a rather paltry, sparse showing, no matter how cleverly the local authorities sought to “plump” things up with gaily-decorated oxen and flowered carts and other such “filler.” And the cheers--there wasn’t such substance to them. They soon died off, unless some tin-helmeted precinct civil guard with a club and a drum roused them up again!

“Why aren’t my beloved subjects besides themselves for joy to have me as their ruler?” the emperor muttered dangerously as he cruised down half-deserted streets in his outsized, double-wheeled golden chariot. What could be the meaning of this staying at home when there was a wonderful spectacle to observe--a genuine emperor with thousands of courtiers and hundreds of foot soldiers and honor guards and horses all done up in gilded livery and gilded weaponry, not to mention ostrich plumes on the horses and dancing girls throwing rose petals before the marching troops?

Humiliated and enraged, Maximian concealed his true emotions behind a mask of genial imperial good-will as he saluted the various commanders positioned along the route. At Thebais, however, he had had enough. Feeling that if this mockery went on, he would continue only in abject disgrace the farther he went, he halted the royal entourage, determined not to proceed until he exposed the cause of the thing that was destroying his happiness.

His tent was erected outside the city walls, for he chose not to reside in the city itself, disdaining the offered palace of the late client king. As soon as the city officials had cleared out, Maximian turned on his advisers and senators. “What is the meaning of this?” he demanded, waving away a slave with rose water to wash his fingers and face for dinner. “I refuse to go one step farther without an explanation!” The generals and officials in the royal tent were thunderstruck. No one wanted to tell the emperor the truth, and only the ones whom everyone despised as self-serving opportunists were capable of such perfidy, and they hardly wanted to be given good reason by a secret society of anti-Rome agitators to quit the country in an hour after the emperor had departed or suffer the consequences. Everyone recalled what had happened to another such Augustian, Aurelian, cut down in his own royal palace by a chamber-slave. Would this new emperor fare any better if he turned on the Christians?

But Maximian would not be put off. He rose from his chair and stepped down to face a senator, who bowed deeply and shook with something like terror. “Here, Gabronius Egalabulus Hortensus, you tell me. I want to know. Why are people, the best and the worst, staying away from the festivities? That’s a simple question. Give me a simple answer.”

The aged senator with white spots on his red, beaked nose shook his bald head, bowing again, and seemed he might collapse with a stroke.

If the full Romans present were loathe to tell the emperor, how much more the half-Romanized Greeks? How could they tell him they had all become Christians, and that Christians despised his gods? Surely, he knew that! If he was a pagan, and Maximian was such, why then was he putting them to a test by which they had to break with him in order to remain true to the Christus? Surely, he knew what he was doing. Yet the emperor himself was breaking the unspoken rule of thumb that had been followed for over ten years. A Christian might remain one, silently, but if he tell, then the laws of Rome would fall upon him like a wagon-load of bricks!

Maximian’s face flushed. He pushed aside the doddering octogenarian and reached a general of the Theban Legion of Thebais.

“Antonius Graccus Verus!”

The commander bowed and knelt, saluting, then lightly brushing the foot of the emperor with his lips as had become the new oriental custom at the imperial court.

“Tell me what I need to know! If you don’t, I will exact somebody’s life and blood!”

The commander’s weathered face blanched. No one dared look about or whisper aside to anyone in the tent for a long space. He rose and looked the emperor in the face. “Yes, I will tell you. We have become all Christians in this city, and in many a like city throughout the East. It is not like it may be in the West--we serve Christus the Victorious One here and everywhere, and praise be to His Name! We still honor you, our temporal authority, but we know a Greater Lord and King, the Emperor of heaven and earth for all eternity. That is why people, high-born and low-born, stay away, for they perceive that you serve lesser gods and even consider yourself a god.” The gasps around the room could not be disguised. Antonius was a brave man, indeed, for it was exactly the case. What he had declared publicly should command the death penalty, for, with laws and imperial decrees still on the books against Christianity, it could only be taken as sheer insurrection. The emperor seemed about to say something, then reconsidered and spun around without argument, and went and sat down. Entertainers were rushed in, and those dignitaries who could escaped from the dancing of naked Corinthian slave-girls.

The party arranged for the emperor and his court was cut short by the emperor calling for his writing court scribe and a courier. Soon a decree went to the Theban Legion quartered nearby.

“I, Maximian, the Most Exalted Caesar Augustus along with Diocletius as Divine Guardians of Rome and the Empire, command you to attend on the morrow a most noble and solemn sacrifice I shall make to my exalted gods and the gods of Rome. You will assist me in the holy sacrifice, and then you will take prescribed oaths to obey the gods of Rome and your Emperor in all things he commands, and, finally, you will accompany him to Gaul, where the infamous sect of Christians abounds to the detriment of the peace of that dominion, and put all, men, women, and children, to the sword.”

Commander Antonius accompanied the royal courier to the Legion, and he read it out to the six millennariums, who in turn declared it to the ranks of 6,666 legionnaries.

All were terrified and appalled. Not one, including the commander, could obey the decree in any respect, since all were Christian--all!

Only one man present was brave or foolish enough to approach Maximian concerning the possible lack of probity in his latest decree. This was Prince Albanus, a cultivated, rich northerner from Britain, touring the southern provinces and well-known enough at court to be invited to visit the royal procession. No Christian, he did not fear the wrath of the emperor so much as often-persecuted, officially proscribed Christians, and his reputation for being a man of sobriety and wide philosophy had proceeded him, gaining him place in the royal presence at Thebais.

He bowed, presented a rich gift of Spanish gold and Tunisian peacocks in gilded cages, then indicated he wished to speak. The emperor, out of sorts, complied, though he hoped for the man’s sake that he didn’t present something annoying, like a a request for a monopoly in some line of trade or business, or a high appointment in government, or some such slab of honey-glazed pork. It was to be expected, of course, from every purling flatterer and sychophant lying in wait along the royal route--but this was not the time, since the “Theban Question” had become the emperor’s chief preoccupation.

“People are saying that you have commanded a sacred sacrifice, Divine Caesar!”

“Yes, yes, what of it?” Maximian smiled thinly.

Prince Albanus shrugged. “It is a noble thing to do in Hellas, to be sure. They are a most religious people, I have already observed, though I have been visiting here only a few days. But--but--”

The emperor stiffened. “What contention do you have with my order? Don’t beat around the bush like cunning, treacherous, slippery Greeklings, or--” The threat seemed to freeze the blood in the veins of everyone present but the cool, deliberative, northern prince. He spread his hands graciously, took a long breath, and proceeded. “What purpose does the Royal Majesty have in mind, if the sacrifice is one the people may find odious to their own beliefs, for I have been told they are all followers of a new god called Christus here, not the ancient, traditional gods of Rome which we revere from our father’s knees?”

This was intelligent enough, and the emperor seemed to shift on his chair, though he quickly drew himself up, recovering his sense of who he was. “Well, we are not about to explain what our meaning is, if that is what you are asking--?”

The prince was no such fool to question an emperor’s motives. That would be certain death.

“No, what I am endeavoring to find out myself in this case, Most Exalted, is what use it will be to you and Rome to force these Christians of Thebes, though they are the Legion, to sacrifice on an altar they consider alien to their faith? That is not in the best spirit of Rome, as I have learned it from my father’s knees, for he taught me that Rome was a mother able to take many religions upon her lap and to her breasts, having milk of charity and tolerance for all, without partiality.”

The prince had the emperor there, and the emperor saw it at once. He smiled, however, and knew that there was only one rule higher than reason, and that was royal privilege. He was, if that was not sufficient, divine as well. That gave him his edge, an edge that was not raw, brute force. Calling the prince forward as closely as a bosom friend would, thereby laying aside his haunting fear of assassination for a moment, the crafty Maximian so spoke to Albanus in order to catch his slightest reaction. “Oh, I will not oblige them to burn incense to the old gods of Rome, deserving as they are of all men’s allegiance. I too am a god, though not so old as they. No, they shall sacrifice to me, their living god and Savior! Surely, there cannot be any objection to that. Who else can these men serve but me--their god and Savior? Who else? If they should think there is Another, that dares to exclude me as his peer, then--then--”

The prince’s eyebrows lifted, and he seemed to see something horrible and even monstrous that he did not take pains to conceal. “Ah, but it will be the same test for them, in either case. They may hold fast to this eastern god Christus.”

The emperor nodded, smiling. “Oh, I know, no one believes in Latium’s and Etruria’s old gods anymore.

Those of Hellas haven’t fared any better, either. As educated men, we understand that, don’t we?

But the formality and the ceremony and the oath-taking are most useful in governing so large a state and empire such as mine. To hold together and prevent outrageous, barbarous chaos breaking down all noble civil institutions and social intercourse and making us all animals, men, patrician or common, must obey something higher than themselves, and so any empire must have gods just as we have.

That much unbelief--that the old gods are mere, charming fictions--I will accept since it has gone on this way too long to turn the cart backwards in its tracks.

But in the place of Vulcan, Mercury, Mars, Diana, Minerva and Father Jupiter, where they used to stand in the people’s hearts I now must stand, and there is no god beside me but Divine Diocletius in the pantheon of holy Rome! If there is no other god of Rome but him in the West, then logically the deified Augustus before you must be god and Savior to all who live here in the East! And if these Thebans think there is Another, whom we have not seen fit to share our throne, then we shall have trouble between us! For I cannot recognize a Rival, and surely I will not recognize this one they call Christus! After all, what is he? What?”

“I know nothing of this strange eastern deity called Christus, Your Majesty,” the prince acknowledged. “I would be wasting your time to pretend I did.”

Albanus bowed, a sign that he no longer wish to pursue the question.

Maximian, having warmed up, was disappointed. He liked a good debate when he was, at rare intervals, presented with an intelligent man who could speak his mind without base flattery and “Greek oilyness” of subterfuge and evasion.

“Wait a moment,” he said.

Albanus took a step back toward the emperor.

“Lord Albanus, as a fellow student of philosophy, we am refreshed by your brave northern manner and no-nonsense plain-speaking, “ said Maximian, rising from his chair. “You may attend your emperor when I go to the sacrifice and the taking of oaths. It ought to be an interesting spectacle, and I want you, our guest, to be shown everything that takes place here, so that you can tell it to your people on your return to your home province.”

Albanus, not showing either delight or chagrin, bowed, but not particularly low, nor repeatedly, as was becoming the slavish fashion before such uxurious tyrants as Maximian. Not particularly pleased by Albanus’s few, abbreviated bows and his lapse in protocol in neglecting to kiss the emperor’s foot, but seeing it was too late to recall the honor, the emperor let him go. The British nobleman, returning to his own tent, paused to have one word with his journey-companion, a millionaire Gallic nobleman by the name Urbanus Fabius Flaccus who owned a number of ships at the ports of Marsailles and Arles and some important estates adjoining those cities.

“Well?” Urbanus said, a heliotrope-salved rag around his throat and a nose stuffed with mint and cloves because he was nursing a bad case of congestion. “How did the royal audience go? Did you get to speak with him? What is he like, this new emperor? Here I pick up this wretched Greek distemper in Corinth, when I had a chance to meet the emperor myself, and maybe ask him for a little monopoly or two in the eastern ports for my merchandise!”

Albanus glanced at the tent walls, which he noted were thin enough to pass the shadows of sentries crossing paths on the north/south axis. He shrugged, then sighed and sank down on his bed cushions. “He disappoints me. He is no fool. He clearly sees what endless darkness he is dragging these men into, but he is determined to do it anyway, all for the sake of his wretched royal pride!”

Urbanus, scandalized, nearly blew the herbal stuffing in his nose across the room.

“What are you speaking about? ‘Endless darkness’? ‘Royal pride’? ‘Pompous windbag?’ Surely, you aren’t speaking of the Divine Imperial Augustus?” “Surely, I am! He is a pompous, old windbag, so fearful of his life, they say he won’t let his wife wear use hair-pins! I heard he had a tremendous fit the other day after finding a Cretan spider in his tent! Thought it was some kind of conspiracy, and was going to call out the Navy and Army and pull every mountain of Crete down into the sea, but was finally persuaded that Greece had such spiders too on the mainland, and poor little Crete couldn’t be blamed. And now he intends to put an innocent multitude to death, unless he relents in the face of common sense and ends this madness he has started!”

Afraid spies must have overheard, and they were dead men, Urbanus collapsed with a coughing and sneezing fit, so that was the end of the matter.

Roll Call for the Theban Legion began at the crack of dawn as usual.

The emperor only arrived at the scene when the court priests had everything prepared for the sacrifice.

For half the night legionaries and gangs of conscripted slaves had labored by the hundreds in feverish haste to set up the altar, then erect the dais on which the emperor would preside over the ceremonies. At noon the sentries alerted the camp that the emperor was approaching. Gilded-hooved Arabians carrying ministers of imperial protocol rode into camp, saluted, and hurried to the general’s tent. Last minute instructions were given the commander, and Antonius said that everything would be found in proper order. Then Antonius went out and assembled the Legion, which ran forward to the parade ground from all quarters of the camp and stood in rank for the emperor’s review. Standard bearers were in place at the head of the Legion, and everyone had worked hard to appear in perfect battle dress for the inspection of their sovereign and chief commander, Co-Emperor of the Greeks and Romans, Maximian.

The wind was strong that day and tore at the flags and garments of the men, but no one moved as Antonius walked up and down on his own inspection, seeing that everything was as it should be.

Finally, the emperor’s entourage reached the perimeter of the Theban camp, and there it halted.

A pre-arranged signal blast from a trumpet, and all the men in the legion roared their response to the emperor’s call to arms.

Raising their swords and spears, and bows, the Thebans presented arms, then dropped them simultaneously, moving their feet and bringing them together so smartly that the sound was like a crack of thunder.

Then silence: all the more impressive since it followed so abruptly.

The renown of this Legion had traveled to Rome, that it was among Rome’s best, and looking out across it there could be little doubt that these were Rome’s finest, or among the very best that Rome could claim from Cadiz in Spain to Babylon, from Treyes in Germania to the Third Cataract. The almost uncountable faces and bodies of the young and highly disciplined soldiers, all looking straight to their commander, Antonius, as he stood alone facing the supreme commander, Emperor Maximian--the spectacle was exciting even to the veterans of such military reviews that happened to be present in the court or among the noble guests.

Albanus and Urbanus, seated in the guests’ ribboned, guarded enclosure to the side of the royal pavilion that was erected to shield the emperor on his dais, were impressed at the exceptional smartness of the legionaries. He had seen Rome’s, the Praetorian Guard, in parade, but these, he observed to his companion, were no whit less a credit to Rome--in fact, he saw they were better. The Praetorians could afford magnificence in unforms, but these Legionaries were magnificent in spirit. Not decadent and sated with the capital’s fleshpots and brothels, the Thebans all looked like youth in the finest flower, before innocence had been stripped away by civilization’s inescapable vices.

“These lads are absolutely splendid!” Urbanus agreed in Albanus’s ear. “Splendid!”

There were many religious personages present, as if it were not a civil court were sitting, but rather a priestly function. The priests, sybils, enchanters and sorcerers of the royal cultus--for Maximian had been deified the year before in Rome by decree of Diocletius--went and bowed before the god, who was garbed in his richly-jeweled, ceremonial garments befitting a divinity. He wore his high-crowned tiara as Maximus Pontifex, not an imperial diadem. The altar was lit with burning coals, and priests held ready beside the sacrificial incense, ready to pass golden lavers containing incense to the officiating high priest who would present the incense on the altar to the god, Maximian.

This was done, and as the incense burned, it was Commander Antonius’s turn to worship and take the oaths of absolute obedience.

Coming forward, he presented his salute to the imperial standard and then bowed to the emperor and kissed his outstretched foot. But when the golden dish was presented, he did not reach out and take some incense and throw it on the altar, and then raise his hands and adore the god-emperor in worship--the requirement for publicly acknowledging total allegiance to both Roman religion and Roman state all conveniently personified in the emperor.

Noting this lapse, despite the shock that nearly paralyzed the attendants, the emperor signaled for the second decree to be read out, prepared for just this circumstance.

“Declare your allegiance to the Most High God and Savior, the Exalted One, the Holy Augustus of Eternal Rome, Maximian the Great Benefactor of Mankind. Do you declare, or not declare on pain of death?”

“You are not my god that I should worship you, Exalted Augustus! Nevertheless, I declare full allegiance to you my emperor and supreme commander.”

The emperor signaled to the reader of the second decree.

The lictor resumed the reading. “You will accompany your god and emperor, and proceed against the Christians of Gaul, and put them to the sword, every man, woman, and child that is Christian. Do you swear to do this, or not swear on pain of death?”

Antonius lifted his eyes. He was looking toward the emperor. He shook his head.

The emperor seemed to take stock for a moment, then he called his chief general, and the general took the lictor-reader, and the chief priest, and other attendants and they left the pavilion, with Antonius still standing there, and went down to the ranks.

The same demands were presented, all down the ranks, and though the time dragged while the emperor took sips of ice-chilled Rhodian wine from time to time as the commands were given out to the 6,666 men, the emperor waited. Not one Theban stepped forth to sacrifice the incense on the emperor’s portable altar, nor take the oath acknowledging him as god, nor accede to the demand to accompany his emperor against the Christians of Gaul.

The flustered general and priests returned to the enraged emperor empty-handed.

Maximian, seeing how it was going, was prepared. He turned to his general commanding the elite Immortal Six Hundred, his mounted royal bodyguard. Well aware that the Legion, in revolt, could rise up and put Antonius on the throne of Eastern Rome, he proceeded with caution. Reduction of the legion must have first priority. Let them see who really was in charge, Antonius or Maximian.

He spoke quietly to the general. “They must be punished. If a sufficient number are punished, the rest will see reason and act like sensible, patriotic armymen should and obey their emperor. I will forgive them, and spare their lives, but first some must be punished to provide the means of repentance for the others.” Then he gave the order for every tenth legionary to be put to the sword. Urbanus, hearing what was to be done, was so sickened that he begged leave to go. Albanus hissed, “You cannot! It will be taking your own life and probably mine too, for the emperor will note it as a personal insult, and send a sword after us too! No, we must stay to the bitter end!”

As they watched a strange thing happened. The commander, Antonius Verus, left the emperor’s pavilion and went and took the place of the first tenth man doomed to die. Too surprised to countermand the move, the emperor deliberated for a moment what to do with his counsellors. The whole army seemed to stiffen in resolve seeing their commander standing in the ranks, giving up his life for one of them.

“By the gods, now what am I to do?” Maximian cried with exasperation to his generals. “He’s put spine into every last one now with this treacherous and foolhardy act!”

The generals were hard put for a suitable strategy. “If we remove him, Glorious One, the damage has been done. Their morale is the highest at this time, and removing him will do nothing to lower it. They have seen his self-sacrifice, and will resolve to follow his example!”

“Yes, yes!” the emperor spat at them, so angry he stomped on the blue footstool under his feet. “I can see that, fools! What I want is to destroy his witness to them! I must destroy it!” But with what means? How? There just wasn’t time left in the day to come up with some way to discredit the commander. “Oh, well, then kill him with the rest,” the emperor commanded, resigned to the inevitable. “Let them all see at least that not even he will escape punishment for his insurrection against my authority and Rome’s high gods!”

When, a hour or so later, 666 Theban legionaries and their commander lay dead on the ground in the First Decimation, the emperor thought the whole thing was over. Surely, he reasoned, the survivors would think twice about defying their supreme commander after witnessing at close quarters their companions cut down as miscreants and traitors to Rome.

The same sacrifice and oath-taking and command to go slay the Christians of Gaul was given to the 6,001 Legionaries, but the same response came back to the emperor.

Visibly angry, the emperor rose from his chair, brushed off his hat as Maximus Pontifex, and issued another amendment to his Second Decree. The Second Decimation proceeded, and six hundred more Legionaries were slain by by the general’s swordsmen.

The same things were put to the surviving 5,401 Legionaries, but not one would throw incense on the altar to the god Maximian, nor take an oath to him as god and emperor, nor accede to the command to kill the Christians of Gaul.

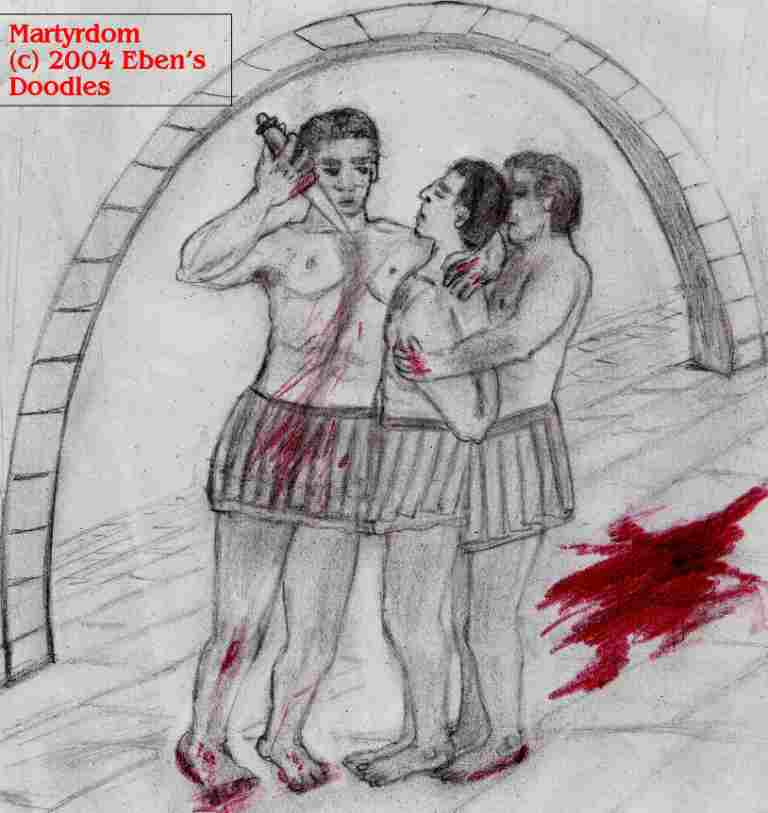

Albanus and Urbanus could hold their eyes shut, but they could hear the slaughtering and death rattles of the remaining 5,401 by the general and his swordsmen at command of the emperor, and the stench of the blood flowing like a river across the entire parade ground--that was too much for Urbanus, and he fainted dead away. After being made to witness these events, Antonius himself was not spared. Stripped of his rank and his uniform and made the butt of the officers’ ridicule, he was given the choice between the sword and strangling, and he chose the more merciful sword.

Albanus was forced to get a slave to help carry the ghastly pale, upchucking Urbanus to their tent.

For an afterward, as a multutude of crows descended, they stayed there, recovering as best they could from the indescribable horror of that day’s events. The emperor had departed long before they did, so they were not disturbed as they left the tent where it was, taking just what they wanted to carry, and leaving the rest for camp scavengers.

All they wanted to do was get as far away and as fast as they could, fearing a stampede of grief-stricken relatives of the legionnaries from nearby Thebais! Already hundreds of newly-made widows and terrified families, hearing the worst, were thronging to the outskirts and trying to get past the guards posted by the emperor.

Albanus kept moving, in fact, until he reached his own home in Britain. He had seen the chief glories of Rome, but also the black monster at its heart. Two decimations of the finest flower of Rome’s fighting men, then a total massacre, for no reason but a madman’s overweening pride! It was enough evil for a lifetime.

As for the Thebans, he pondered many hours about it both on the journey home and night after night when he could not sleep. The whole scene and the significance of it haunted him.

It didn’t help that he had a vision of a dream-bridge, shining blue like those sapphires with stars in them, and the slaughtered Thebans were again alive, assembled to fight, and all were defending the glorious bridge under construction against a red-flaming star and also swarms of what looked like silver boats sailing without water in a blackest of black seas. On the other side of a curtain-like division, hordes of spiders, bats, and serpents which were tying to tear a mirror-image of the bridge to pieces while other champions stood upon it and fought them. What could a doubled-vision like that mean? Albanus was a man of reason and philosophy. This dream lay beyond the reach of his books and his studies.

Yet the question that came with the memory of what had happened in Greece haunted him just as much. “To a man,” he thought, “to a man the 6,666 and their commander proved so utterly devoted to this Christ-god of theirs, that they willingly sacrificed their lives! What believers in other gods would have done the same? Everyone else can boast only a half-hearted belief compared to the Christians. When faced with recanting their Christus or dying, they choose death as a privilege to suffer and not a calamity to be feared!”

He thought about this for days and weeks. He could think of no god, other than this “Christ,” who could command such absolute allegiance. Certainly, sorely-oppressed or degenerate men, counting their lives cheap, died every day for tinpot gods, or fought to the death for them, but not like these 6,666 had, all who were in the prime of manhood and had no reason to despise life.

What difference did it make to sacrifice to one more god? To any other citizen there would have been no problem in sacrificing to Maximian, or taking an oath to him.

Why did the Thebans take singular exception? Why couldn’t they sacrifice to Maximian? It was understandable that they would not want to slay fellow Christians, but why couldn’t they sacrifice to Maximian as god?

Everyone knew it was a ceremonial state honor, not something you truly had to believe.”

Prince Albanus could not come to a satisfactory answer on his own about this. But as he was sleeping he heard like a trumpet’s clarion call to battle the same verse that had run through the ranks of the dying and doomed 6,666, “Whosoever therefore shall confess Me before men, him will I confess also before my Father which is in heaven.”

This statement brought Albanus sitting bolt up in bed and looking around in the dark. He called for a lamp to be brought and searched the bedchamber, but no one was discovered in hiding.

Feeling himself a fool in the eyes of his chamber-boy, he went back to bed. But the statement came again, as he slept.

In the morning, unable to keep his thoughts off it, he determined to seek out counsel among the religious community. He knew of some Christians in the southwest of the country, and was about to go there in search of an answer to his mind’s turmoil when someone came to his door.

“Amphibalus,” the kingly, silver-haired gentleman caller named himself. “I am being pursued by enemies of my Lord, for I am a believer of Christus. If you fear them, leave me to my fate. If not, spare this old man.”

Here Albanus had thought he had left the issue behind, but it had followed him right to his own doorstep! Should he send the man away and remain loyal to the emperor and the law against the Christians? Or should he take him in and risk the consequences of sheltering a fugitive?

Anxious to get to the bottom of his own questions, unafraid of the men who were in pursuit, Alban invited him in, and set close watch on the door and the outer gate.

They had just got to the essential teachings of who Christ was and how He was the Perfect, Complete Sacrifice and Ransom for fallen men, when Alban heard a commotion at the gate of his mansion, and knew it was going to be trouble for him.

“By order of the emperor, open up! We have arrest warrants and are searching for a criminal of the state, proscribed for crimes against the gods of Rome!” the commander of a troup of horsemen shouted.

Calling off his own men who were struggling to hold the gate against the experienced troops, Alban hurried the ecclesiatic up the stairs to his bedchamber, and got his robes and chain with the cross and put them on. Then he left the man there and went down to meet the Romans.

The troops, seeing the neck chain with the cross and the robes of a Christian bishop, seized Albanus, and carried him off to the Roman governor.

The governor recognized Albanus, however, and shook his head.

“My lord, I suppose you have done this for some high philosophical purpose! But I am not impressed. I must do my duty by Rome and the gods. Just as I would have ordered done for the Christian we seek, I must order done for you, as you seem to have taken their side in this struggle.”

Incense was brought, a lighted brazier, and Albanus was escorted to the statue of Jupiter seated upon a throne.

“Lord Albanus, sacrifice to them,” the governor commanded, “and preserve your life and holdings. I will still give you a heavy fine for giving succor and aid to a Christian! But because of your rank, I will grant you the benefit of a doubt, the chance to prove your reverence for the gods. Be sensible and take this opportunity to rectify your piece of deceit!”

Albanus shook his head. “Deceit you may call it, but I cannot sacrifice. I have seen too many noble, young men die for this same thing, and I would not betray their sacred memory!”

The governor was surprised. “But you, reputedly an educated man, couldn’t have let them turn your heads to their own Christian god! Sacrifice, and I will let you go free! It is such a little thing to throw a pinch of incense on the altar. Be reasonable! Be patriotic for Rome’s sake! Rome cannot stand against the barbarians all around if her leading people forsake her holy altars!”

The prince stood his ground. “I have decided in my heart and mind. I will not sacrifice to another god, for there is only one God, even Jesus the Christus! All others are puffs of wind, vanity, the products of mortal men! And you and know it they are not worth worship!”

The governor was enraged, and he gave orders to have Prince Albanus, a patrician of Rome, scourged. Normally, citizens could not legally be flogged, but he held special decrees of punishment for Christians within his authority, and whether they were citizens meant nothing to the emperor Diocletius, who had turned against Christianity and joined Maximian in persecuting them with all the powers of state.

Roman floggings were intended to be severe, near-death punishments. Albanus’s back was ripped open, showing the muscles in a line to each side of his exposed backbone, yet he refused to beg for mercy nor give up his claim on the Christus.

“Then I shall prosecute you to the fullest extent of my authority and the imperial decree!” the governor declared, and he gave the order for Prince Albanus to suffer the full penalty of resistance to Rome, decapitation.

This done, the executioner, seeing how well Prince Albanus had behaved during his torture, and how he took his death sentence, threw himself down across the body of the beheaded man of God. “I too take and confess this Christus, the Great God of all the earth, which this innocent man confessed.”

The enraged governor had the executioner also put to death, thrusting him into the same fabulous darkness that had first called the noble prince. Now Prince Albanus was the first British martyr and his executioner the second. In time the mighty governor commissioned by Imperial Rome would die and become dust,and his name and his deeds dust. But Albanus shone from the grave, brighter and brighter, with his executioner.

Yet the orders kept coming down to the men in the ranks--”You must sacrifice to the emperor as a god or refuse on pain of death!” “You must swear an oath to him as god and emperor!” “You must attend him on a campaign against the Christians of Gaul!”

Alexandros was appalled, and he felt that others around him were also of his mind about such commands. How could he obey any one of them and remain a follower of his Lord Christ? He would become a Judas betraying his Master! If he took the oath, he would be another Peter, swearing and cursing and denying that he was a follower of the Lord.

Alexandros waited to see what would be done, having made his decision not to obey. He was terrified, but he dared not obey.

Then the counting began by command of the first millennarian, and Alexandros came up as a Tenth. His thoughts whirled. Why were they being numbered? Weren’t they all to die gloriously together? Not so?

The executioner, stripped for the task, approached the Legion standing at attention.

The emperor, up in his golden pavilion, watched with all his glittering courtiers and bodyguards. The wind furled the emperor’s flags, but the standards of the Legion were ordered to be held at half their height, signifying their disgraceful rebellion and the emperor’s displeasure and punishment.

Sweat poured down Alexandros’ face. His mind flooded with the images of his wife and their first child. He saw himself executed as a traitor to Rome. Now what would happen to his loved ones? They would not only lose him as their support, but they would be named with him as traitors and enemies of the people and state. They would be hounded and forced out of their tiny house. It would be seized by the authorities. His wife and child would starve, since relatives would be imprisoned and their houses seized too if they dared to take them in.

Alexandros looked as far as he dared down the rank to his left, for he stood almost at the beginning except for the nine to his right.

The executioner with a sword approached the head of the Legion where Alexandros stood waiting for death. He had trained for war, and was brave enough for that, but this waiting to be cut down like a gutter dog, that was nothing he was prepared to take, and he could scarcely summon the strength to stand and not collapse in disgrace on the ground.

But someone was approaching even faster than the executioner--Antonius? It was! What was he going to do? Alexandros wondered. Countermand the emperor? Impossible!

Without a word, Antonius reached Alexandros, giving him a silent sign to step out of the ranks. Obeying, though in a daze, Alexandros took a few steps, stopped, and looked in utter amazement and perplexity as his commander stepped into the place between the men’s shoulders that he had just vacated.

The whole Legion nearly erupted in amazed shouting, but that could not be done, of course, and somehow they remained silent, their eyes proclaiming what their voices must not.

The executioner was stopped in his tracks by the sight. The emperor’s soldiers, attending him, also halted, and then looked back toward the generals and the emperor in alarm and confusion. One went running back to their headquarters.

The whole Legion held its breath.

After a few minutes, a man in splendid clothes came riding a horse, reined sharply, leaped down and spoke to the waiting attendants and the executioner, and then returned to the emperor just as hastily.

Faces set grimly, the emperor’s execution squad once again approached the Legion.

The whole Legion’s breath seemed to go up at the same moment, as they saw what had been decided. Their commander was to be disgraced and dragged away. But that wouldn’t disgrace him in their eyes! Never! He had performed a most noble deed, to stand as a commoner among them to take their part in death! He was forever glorious in their eyes, to their thinking. So Alexandros thought, and all thought as he did.

But the executioner and the imperial guards did not take Antonius in hand and pull him from the ranks with violence. Instead, he went and submitted to slaughter like a sheep without resistance, and the men held him as the executioner positioned and then, in a movement too quick and practiced for the eyes to follow, rammed a sword into the breast from the upper chest region where there would be no obstructing bones.

Alexandros, seeing this, felt all his blood drain out of him. He moved in a trance all down the line, not knowing his place. His commander dead for his sake? He did not know what to do.

Finally, a millennarian called out, “You! Go to the end of the lines and take your place for the next counting!” And Alexandros stumbled away as he was bade, but before he took more than two steps a wind struck the Legion, whipping so much dust up that it cut the Legion off temporarily from the sight of the emperor and court and guards and separating the 6,666 from the executioner.

Nothing could be done until the terrific wind died down and the dust settled. Meanwhile, the cloud’s roof seemed to be wrench off in an instant over the Legion, and there were two gigantic silver wings poised, silently beating in place, gold shining underneath on the feathers.

Transfixed, the legionnaries stared upwards, not knowing what it could be. Were they the wings that had beat up the wind and dust? But the wings then began to slowly descend, while beating slowly and grandly over the 6,666 and their fallen commander. As if they stood in the lee of the storm, there was no wind, only utter stillness into which the sun poured in a blinding brightness beyond its powers, so that if it had not been the sheltering wings shading them, they might have been consumed in so much radiance.

Suddenly, a voice from the ranks cried out verses from a psalm.

Yet a final voice cried out to them, and it was as somber as it was triumphant.

Given heart, however, the Legion squared its shoulders, to a man, as all realized that God’s Will did not include a miraculous rescue, their deliverance was not to be--many of them would soon be joining their commander where he stood before the Lord God in eternity.

With no further delay, the Decimation proceeded, from the first Tenth to the second, to the third, and so on.

Alexandros found the end and stood there, but the executioner turned back away before reaching him. The execution was over! The survivors, shocked by all that had happened, thought that mercy and clemency would now be granted by the emperor. Surely, they had suffered enough, seeing their beloved comrades slain and their commander also put to death!

But something was wrong. The emperor’s trumpet corps blew no reprieve and no order to disband back to quarters was issued. The hot sun continued to beat upon them with very little wind. Their sweat continued to pour down their arms and legs, attracting the biting gnats and flies.

Instead of orders to fall out, orders came repeating the emperor’s three commands.

Again, Alexandros was faced with whether to turn traitor to his Lord or sacrifice and take an oath to the emperor as god and also go and put to death the Christians of Gaul, or save himself, his wife and his child from death and disgrace.

But again he could not find it in himself after hearing the words from God and seeing the great wings of silver and gold signifying his authority and protective providence. He knew his wife would never approve if he forsook the Lord for her sake and the child’s sake. She loved the Lord just as much as he did, perhaps more. And he could not live with himself, he knew, if he lost his Lord by his own choice. What was there worth living for greater than the Lord Christ?

Alexandros again, with all the others--for none would give up Christ on the second tally--cast his lot with his Lord against the emperor as god. The emperor’s command was issued: a Second Decimation!

Was the emperor raving mad? Six hundred and sixty six had died the first time! Now six hundred more would be killed for no good at all to Rome.

The executioner, a new one, for the previous one was worn out, came and the work proceeded, starting with the first Tenth, and then going on to the second, and third, and so on, all down the line. This time too, though being put with the 66 centurians in the counting, Alexandros did not come up as a doomed tenth.

Sickened by so much killing of comrades, weeping from knowing them personally and seeing themj die just a few feet away, Alexandros was beside himself when a vision nearly swept him off his feet, it was so strong and overwhelming.

With his comrades ranked in formation, he stood as if upon a span of uncountable stars like the sands of the seashore, and he and his fellow legionnaries fought with flame-throwing swords against a red-flaming star as well as against sleek, metallic galleys that flew more swiftly than arrows.

They stood on their bridge, for that was what it appeared to be, and somehow withstood the first attack, though there was damage inflicted by their enemies all around and even to the bridge by the star and its allies. And for what were they fighting? What was this Bridge, and why was it so fiercely contested? Alexandros had no idea, except that he felt the answer in his being, rather than mentally grasped it. Somehow the Bridge was everything put together that he had ever wanted to see happen in his life and in the lives of others--it drew all such elements together and linked every human heart and soul together in a bond that could never be broken--that was the meaning he sensed but could not put in meaningful terms his mind would accept. For the opposite reason, that the enemy wished its annihilation in order to break apart all such last human-and-divine communion and commonweal that the Bridge contained--it had to be destroyed.

When the red star withdrew to seek another strategy for its forces a White Star, the Bright and Morning Star Himself, came and enveloped them, bearing them away into the heart of its own brightness, and then Alexandros found himself, his shoulders being shaken by a centurian demanding that he be a man and not lose his dignity before the others.

Alexandros stared at the centurian, unable to tell him what he had just seen, and made a great effort to control his tumbling thoughts and emotions. He was barely aware, evenso, when a third counting was made and 5,401 were numbered as survivors of the two decimations.

The mad Maximian’s decree was soon coming: death to all. All!

Alexandros, hearing it, having seen the wings, heard the words of the scriptures from the Psalms, and witnessed the vision of the Bridge that somehow he and his comrades would one day defend in a far place in the heavens, hardly cared that he was marked a dead man by the fat, old man on the golden throne.

He just wanted to get it over with. Resigned to his death, he yearned with all his heart to take his place with his comrades in the final battle pictured to him in his spirit, forming the Lord’s Legion of 6,666 Theban martyrs and their commander, a fighting force of which no Roman emperor could ever be worthy.

The executioner at last reached Alexandros. The sword was poised at his breast.

“My Lord and my God!” cried the Tenth Man, and then it happened. Even before the sword plunged he felt his spirit plucked right out of his body, so that he never knew the pangs of death.

Dust storms and hail dropping from a cloudless sky also afflicted them sorely.

Though surviving the universal hatred of all Hellas for his foul deed, Maximian could not avoid being surrounded by Greeks which formed the vast bulk of his subjects and found himself literally beseiged in his palace at Constantinople. Though he set a double guard, one to guard, the other to spy on the others, he could never find rest during his reign, and if he could have escaped by ship and not expected the Greek crew to throw him overboard the first chance they got, he would have left Constantinople immediately.

As for a safer land trip, surrounded by a Roman Legion, he considered it, but the abject disgrace he would have suffered, a Roman sneaking away in cowardly fear from a laughing world put an immediate end to this alternative. Emperor Diocletius in the West, catching wind of what Maximian was preparing to do, would not permit it. “Choose what you wish for your winding sheet--a dog’s hide, or royal purple, because I will never sanction your removal from office by a flight to Rome!” Diocletius wrote to Constantinople.

Trapped, he ate and drank himself into insensibility, and before long he was carried off by several debilitating strokes that left him helpless as a newborn in a perfumed royal nursery crib--captive of the very chamber-slaves he so feared. Then, as it must, the night came when an assassin was let into his royal bedchamber. The sleepless emperor waited, bloodshot eyes wide open but unable since his last stroke to scream for his bodyguards, who wouldn’t have come anyway.

It is said that his chamber-slaves hacked off parts of the body and threw them out the palace windows for wild dogs and foxes to gnaw, the palace being situated just outside the city walls since the emperor had a horror of public places.