Strangely, this specific attack had been anticipated somehow, long ago but now forgotten. In the re-discovery of this fact, something even more ancient and extremely controversial, something more like a sigh too deep for human words, or a silent cry from things far older than the Pyramids and the Sphinx, was to be dredged up from the actual depths of the sea. Too bad Bruno wasn’t around to observe things in this part of the world. Where are the Brunos when they are truly needed?

Wild birds--particularly the raven-like, red-billed, red-legged chough--were congregating and moving restlessly about, on land, and doing very little flying.

The largest groupings of the land birds were at Land's End and the Scilly Isles, and tourists remarked about it to their tour guides, it was so conspicuous, but the guides did not know what to make of it.

Word spread beyond Cornwall, probably carried by these same tourists. Bird watchers from all over the British Isles poured in. After them followed helicopter telly crews, who buzzed small Cornish communities and scared the quiet living souls in them half to death.

Televised interviews of experts proved inevitable as well, and authorities in ornithology popped up on shows dealing with the phenomenon. Each authority produced a pet theory why landbirds would flock to the seacoast--though one simply denied that anything out of the ordinary was happening.

"How do we know they are congregating?" remarked Dr. Douglas MacPherson the Oxford don and high-brow skeptic to the interviewer. "No official counts of birds and bird groupings has come in from reputable sources, and until then we cannot say they are congregating or engaging in any communal grouping."

Since the audience had just been shown recent clips of the mass groupings of birds along the coast, the interviewer could not let him get away with it.

"How can you, Dr. MacPherson, deny what we can see with our own eyes? It is preposterous to assert the birds are not gathering together in unnatural numbers, for what reason we can only speculate?"

The expert was nonplused and smiled indulgently.

"But we know that any two people will see the same thing entirely two different ways! What is unnatural to one person is probably quite natural to another. For example, you look out there and see 'gatherings of unnatural numbers' of birds, but I--who haven't your vision--see nothing out of the ordinary. Birds have flocked together before in large numbers, and it means nothing really. So, my conclusion is that what a trained observer as myself sees is a random distribution that happens to coincide with other random distributions. There is, as yet, no verifiable grouping! And as for a newscaster's silly report that they are all turning white, albinism, I would remind you, is a perfectly natural occurence, though I would dispute anyone who suggested that large numbers are involved, since that is a scientific impossibility, most highly improbable!"

The telly audience wouldn’t swallow MacPherson and hooted him off the platform, but not before he shot back, “Photographs are notorious for lending themselves to varying subjective interpretations. Any sane person will agree to that, so why all this fuss about the birds. What some people think they see simply isn’t happening!”

But it was happening, the obstinate MacPherson notwithstanding.

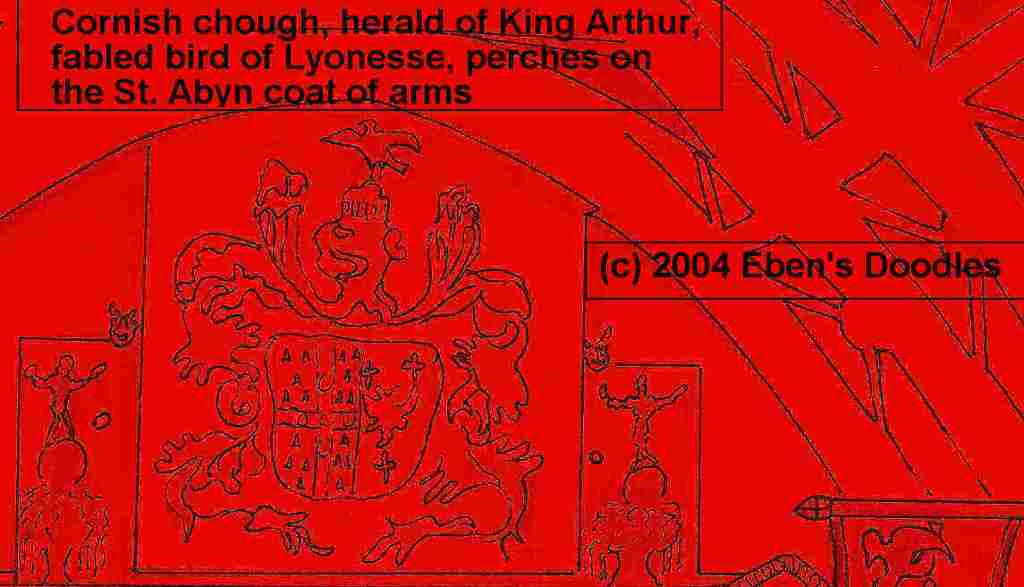

Debate raged heavy on the topic all over Cornwall and Britain. What fueled the confusion was that no one knew exactly what it was and why it was going on. After all, choughs hated the open sea. None had ever before been sighted on the beaches and headlands of Cornwall. Of all Cornwall’s land birds, this one held most tenaciously to the soil--giving it a heraldic and patriotic significance to the Cornish.

Suddenly, in the midst of the furor, the birds were gone.

They had, evidently, all flown off in the night, in tens of thousands.

No one could guess how they all could decide to leave at the same time--getting the word 'round robin' so that they would be gone by six in the morning.

However it was accomplished, the flocks vanished.

The great, sudden disappearance of Cornwall’s land birds stirred up a far greater storm than their huddling in large, nervous groups.

Soon reports came from the Scilly Islands off the coast of Land's End, Cornwall. People reported hearing multitudes of birds passing over in the night.

Then days went by while people anxiously and curiously awaited word.

What had happened to all the choughs of Cornwall?

The dismal answer began washing in on the tides of the second week: the beaches of Ireland, Wales and Cornwall as far as Cowes became littered with dead choughs--their non-swimming habits having proved fatal. Most strange of all, perhaps, was the fact most all were stark white--their feathers having somehow been bleached of their natural black colour.

Helicopters flew back to terrorize Cornish villages and towns. More ornithological interviews took place on high-level talk shows with MacPherson conspicuously absent, while audiences watched and engaged in heated pro and con. But beneath the hoopla of the media Cornwall was appalled to the teeth; the homely chough was as much a part of the Cornish landscape as St. Ives or Land's End. The mass suicide at sea--for such it appeared--provoked considerable, deep soul-searching. Attuned to the rhythms of the sea on which Cornwall had depended for centuries for its livelihood, the Cornish suffered a curious dichotomy of betrayal and outrage. "We've done something wicked and mean and our birds done forsook us!" was quickly followed by "What foul thing has done this to our birds?" Guilt, in other words, was countered with righteous anger. This was an impossible situation for any people to endure for very long. They had to find out the cause, either in themselves or in some hostile outside force.

Then an odd little poem appeared anonymously in a number of local papers, and many people read it and thought well enough of it to pass the word on. The poem quickly spread, since it was pithy and easily learned.

"I'll not rest in this wet cairn, till all the choughs homeward turn."

The two verses about Sir Tristam and Lyonnesse, though not very good poetry, swept Cornwall into a frenzy. Everybody was talking about Lyonnesse, which had been a dead subject for years, snickered at by tourists if a tour guide should be so bold as to bring it up. Now that the Cornish chough had come to a spectacular end, somewhere in the heart of sunken Lyonnesse, the legend revived with a vengeance. Local clubs of Lyonnesse zealots organized throughout Cornwall, competing with the popular annual Gorsedd harvest rites for public attendance.

Many people connected the Lyonnesse legend with Cornish claims to be a separate culture and country in its own right.

"You need to remember you are NOT in England," tourists were reminded by the bolder tourist guides whenever people made the common mistake of assuming it was. "We Cornish were here long before either the Romans or the Anglo-Saxons thought up England."

Thinking to use the controversy to increase its rating, a London station flew a chopper to Mount St. Michael, which was reputed to be part of the original Lyonnesse, and was known to the Carthaginians as the tin-rich Iktis, tin being the uranium ore of the day since it was essential to manufacture of the best bronze weaponry.

The ploy worked. Lord St. Aubyn waved a white table napkin on a pole as they circled the Mount, utterly destroying all the domestic egg laying in the region for the next two weeks.

The chopper landed and the crew hurried to catch the lord before he changed his mind and shut the castle gate on them.

Now the towered gate had long since vanished, but the huge portal doors were thick enough to keep out even this determined a group.

Tall, severe, dignified, Sir Francis Cecil St. Aubyn (variously spelled Aubin, Aubynne, Aubinne, Auben), third Baron St. Levan, Lord St. Levan, looked seventyish but in good health, with ruddy cheeks and a frosty gaze that could stop a charging, steel helmeted, treasury death tax assessor at fifty yards.

But the interviewer, thirtyish but still looking twentyish Marco Viselgraphi of BBC’s “nature discovery series,” had considerable experience and felt equipped to deal even with aging nobility who had in 1940 fought in the decisive Battle of Britain, as Lord St. Aubyn had as a RAF Spitfire squadron commander.

"Sir," began Viselgraphi, holding up the mike as his cameraman zeroed in, "we are fortunate to see you out on the grounds enjoying your well-deserved retirement among your lovely, prize-winning exhibition roses, particularly today, when people everywhere are asking this one question: what made the birds of Cornwall take a dip in the Atlantic? Was it to avoid the Cornish separatist movement, as some other people are saying in London?"

Lord St. Aubyn had decided to treat, instead of retreat, as he stood knee-deep in scrubby heather, not exactly hybrid tea roses fit for the Chelsea Flower Show. He thought he might defuse their attacks on his peace of mind with kindness instead of reclusive intransigence.

So he smiled on the professional young fool, showing some extensive bridgework where he had caught flak in the war. "An excellent question, dear boy! But allow me to think. It is a very complex issue, as you can appreciate in your line--your line of--now, yes, I have a definite opinion on the matter, now that I think about it, and--" He paused dramatically, as if something profound has just occurred to him in the course of six or seven decades. "But, gentlemen, my opinion can wait. I mustn’t let this splendid opportunity pass. Allow me to show you around the castle, keep, and grounds. Why, these doors frames, for example, are prime examples of 13th Century work by Breton stone masons. How do we know that? Look here, dear boy. Can you see the way the grain of the stone is cut transversely and not conversely? Well, that is remarkable proof of T.S. Eliot’s Concomitant Fallacy operating, since stone was being treated as wood, and, moreover--"

Meanwhile, “dear boy” Viselgraphi reacted to the chummy arm thrown around his shoulder and the tooth-rattling chuck under the chin. While disengaging from the friendly lord, he had been making desperate signs to his cameraman, pilot and whoever else was with him. Together, they were backing toward the chopper. Suddenly, they turned and jumped in, and Lord St. Aubyn cheerily waved as they passed overhead, heading straight back to London with considerable clumps of heather caught in the aircraft’s wheels.

Retrieving the table napkin, the chuckling, old man, shaking his head, went in, the business taken care of satisfactorily as far as he could determine. “Just the mention of that dreary old windbag Eliot sends them packing every time!” he thought. He really doubted they'd be back for more Eliot, however much the controversy heated up.

Never really conquered, Mount St. Michael had seen few white flags.

Above the castle fluttered, as always, the St. Aubyn family crest and flag which featured the ancient Cornish chough, insigne which were also preserved in the castle's Chevy Chase Room.

Yet times had changed. Try as they may, it couldn’t be helped.

"Shouldn't we remove it from the flag and crest?" his practical wife asked him one day as she strapped a tiny, jeweled dictionary to her wrist. "After all, the choughs have all turned white feathered and gone--poor little dears! As long as we've got one on the flag, it’ll remind me."

The lord was not so willing to change as the lady of the Mount. The chough, non-existent or not, would stay and fly, on cloth at least, above Mount St. Michael as long as there were St. Aubyns holding down the fort and castle and able and willing to draw a ready sword (unless he turned the castle and island over to the National Trust to elude the deadly amd ruinous Death Tax.

Lord St. Aubyn must have been smiling, for his wife remarked about it as she was searching her paper for an unmarked crossword.

"No, it's not a joke," he replied. "I'm just awfully glad those telly people didn't ask about Atlantis. Lyonnesse was bad enough. I might have said something very foolish if they had pressed me, and then the whole world would have seen me put on the jester’s cap!"

"Oh?" said his wife as she glanced up from her baffling crossword. "What foolish thing might you have said to them, dear? Tell me, I want to laugh at something."

The lord of St. Michael's Mount sighed and scratched behind an ear. "Well, the truth is, Clemmie, a young fellow from Stratford said it best: 'There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy, Horatio!’ I first came close to the meaning of that when I was flying in the Battle of Britain, you know, when I felt--felt those--"

His wife darted a look at him. "Is that so foolish? After all, Bill said it, and I should imagine everybody knows who he is!"

The lord's face suddenly turned grim, putting aside the still vibrant memory of how invisible wings had seemingly supported his crippled craft until he was landed back at the air station, wings that had taken him out of the way a bit, too, granting him a top secret view of certain events off Chesil Banks--events that afterwards nobody in government, American or British, would divulge to the public, since it was obviously so out of the course of human understanding, so obviously supernatural. Naturally, all evidence was destroyed on the spot as soon as possible, and who could expect the Nazis to shame themselves before the whole world by admitting to it if the British weren’t going to spill the beans?

It was probable mysteries like the ones that had literally put wings on his fatally disabled craft and given him a Field Marshall’s tour of the Western Front in 1940 were not going to occur in quite that magnitude again, to his experience, at any rate. Yet this choughs' vanishing act--would it equal the events of 1940, or blow away like harmless smoke? Time would tell. Yet he knew these things usually occurred in groups--like swelling storm waves which hid the infamous Ninth, the really big one, somewhere in the series, and unless you could see clearly enough to count you never knew which it was until your Nemesis hit.

"But do the mainlanders really believe it?” he reflected aloud. “I would wager a million pounds none of them do! Young people today seem to have their minds set in tight, little, correct boxes. That's why this disappearing of the choughs has kicked up such an infernal fuss! It doesn't fit any of their little boxes. They can't explain it in their philosophy--explain it away, that is--so they come and hound people like us after making all the experts and authorities look utter fools!"

Lady St. Aubyn went back to working her puzzle. She sighed after checking in her dictionary and looked up at her husband pleadingly.

“‘British Archaeologist who discovered King Tut’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings; also common term for wagon-master’? Now who on earth would that be, dear? Davis comes to mind, but, no, he was the poor old fellow they said disappeared, gobbled up by a wild crocodile or something nasty of that sort down there. I don’t believe he’s the one they want.”

The lord of the castle, who had crossed paths with the world-renowned archaeologist at various London club and state dinners given in the man’s honor before the war, returned her a piercing look.

“Try C-A-R-T-E-R.”

The lady of the castle set immediately to work. She began to cover the puzzle with a sudden flurry of entries.

A moment later his wife looked up at him with triumph.

“Splendid! ‘Carter’ fits perfectly, and, what’s more, it gives me ’Atlantis,’ ‘rob,’ ‘thief,’ ‘killer’ and ‘fire.’ My, a regular windfall! You’ve made my day, darling!“

But her delight met only a grim, distracted expression.

She sighed and set down her puzzle.

"Oh, you’ve worked yourself up again, dear. But try to think about pleasant, little things, as I do. Leave larger affairs to take care of themselves. Your heart, you know. As for the cloughs, I feel things will work out in the end. They always do."

The undaunted old Spitfire glanced at her, felt a particularly tremendous gust rattle the tall windows, and shook his head--the same that had faced down overwhelming Nazi might at 10,000 feet and, in a tight spot, found, to his lifelong amazement, an Unseen Agency intervening when technology and first-class training were not going to be quite enough. The castle, he knew, would hold to its perch on the two hundred foot high crags of the Mount, but would the Cornish and English kingdom? And what about the world?

The lady dropped all thought of her promising crossword and stared at him.

"What are you taking about? Inscription?"

Lord St. Aubyn sighed a spouse's sigh, and not too obviously, since he knew his own memory was faltering a bit lately.

"Remember? You covered it when you had some painting and refurbishing work done in the Chevy Chase Room--but I copied it down. I put it away somewhere for safe keeping."

The lady laughed. "Now we'll never find it!"

Lord St. Aubyn thought hard for a moment, then went to a small, ornate clock on the fireplace mantel, lifted it and withdrew a slip of paper with a look of Cat with canary in mouth.

"You see, Clemmie, I haven't quite lost all my memory!"

"Oh, stuff and nonsense, read it for heaven's sake!"

Lord St Aubyn slipped reading glasses from his pocket, perched them on the end of his nose, then peered as he slowly translated from the Old Cornish:

to Lyonnesse he up and flies,

Cornwall's Sun, he sinks and dies.

"Oh dear, I don't like the sound of that," observed the lady, seizing her crossword puzzle so hard it crumpled in her hand. "I don't like the sound of it at all! Now I remember why I covered it up. Please stick it away. I don't want to hear about it again!"

Lord St. Aubyn, seeing it was a proper time to make lords of the castle scarce, went for a pipe from a collection he stationed next to a crock of vintage Mousehole hard cider in the dungeon--converted into a wine cellar and over-flow pantry. The cider was warming the old ticker and the meerschaum was drawing splendidly on a select brand of imported Jamaican, “High Wind,” when he came back and found his spouse trying something easier on her nerves, a crossword circle puzzle. His silver-gray Weimaraner had joined her “golden-blush” Shih Tzu on the carpet by her overstuffed chair and looked snug, curled up together, as two titmice in a yarn basket.

She turned to him after he had enjoyed a good smoke, sitting with his uncrumpled portion of the Times, the weighty financial and political opinion sections.

Her eyes squinted as they always did when she needed advice with something rather difficult she knew she could very well do herself without help but, from feminine modesty, could not concede her fairer sex.

“Pugsie, dear boy, just one little question. I promise!”

Lord St. Aubyn sighed behind his paper. Whenever she deployed his moniker, he knew what was coming, and hated word circle puzzles, particularly the esoteric and philosophical sort churned out by Lady Arkenstone, whose books were bound in gilt by his wife and occupied whole shelves in HIS library.

“She’s gone off aery and theosophical again, I fear,” acknowledged Lady St. Aubyn. “I wish she would just stick to the real world, but I can’t put her down at this stage. I’ve done her all these years so faithfully, and friends should stick by old friends, right?”

“‘Pugsie boy” cleared his throat.

“Well, this one has got to be very perspicacious, as they say. It’s definitely perspicacious. I don’t know how she does it at her age, I really don’t! I believe she’s predicting the end of the world!”

Becoming a bit annoyed, Lord St. Aubyn lowered his paper completely. “Well?”

The lady did something unexpected for her. She rose up, upsetting the dogs, and thrust Lady Arkenstone’s latest circle puzzle in his startled face.

Without his glasses, he could see only blurs of letters and words she had circled, so he brought out his bifocals and took a better look.

Taking the puzzle book, he read his wife’s circled letters, then referred to Lady Arkenstone’s “Helpful Hints” page, and finally stole a look at the completed puzzle given in the back of the booklet.

He handed it back.

Standing, holding the book and squeezing it a little too hard, Lady St. Aubyn eyed him with a gleam of impatience. “Well, what do you think of it?”

The old Spitfire squadcom came to the fore in the time of emergency. “Well, dear, dear Clemmie, I can’t take issue with the woman at this date. We really are in a bad spot if it is so as she says. But we must go forward with the stout-hearted boys and girls we can possibly muster. That is the only way to face the lion and the wolf. We must put our best effort into it, and if necessary all the way to the wall with these ‘DUBESOR’ champions and letterman, as she calls them, what?”

The lady, who kept her old Girl Home Guard uniform in a place of honor in her wardrobe holding the jeweled gowns she almost never wore, stared at him for a moment, her fine eyes unsquinted and taking in his whole meaning. Then she nodded slowly and turned back to her "golden-blush" haired seat.

Cornwall was not the only land bordering the Atlantic having trouble with birdlife. Northwestern Spain, Basque country, was another. This time the consequences would reach far, indeed,, in a way that would force the attention of the besieger.

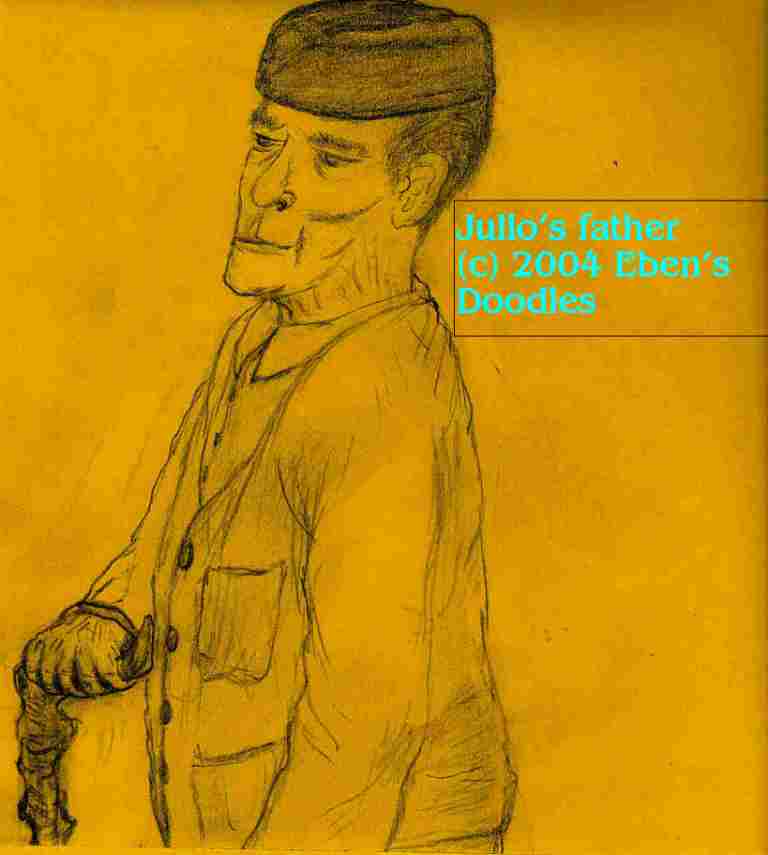

"I better go then," said Julio to his father at the mill, a family operation that, until now, wasn’t directly concerned with anything but producing the best steel in Europe, Sweden notwithstanding. How could they have known that the fate of the common wood dove was inextricably bound up with the Toro Del Fuego Rolling Mills, as they called it?

"Yes! And the Blessed Virgin and the wood dove go with you!" replied his aging parent.

His eyes filled. He himself was twenty, his father--marrying and conceiving late--was well over sixty. How long would it be? he wondered. Yet the old one insisted on coming to the mill and spending the week in work when he could be home, comfortable in a chair, with his wife, who was yet only forty, to wait on his needs.

Julio smacked the papers against his hand as he looked out the window on the glowing foundry below. Already they were a week behind in getting steel to the boatyards, and as a major supplier they could not afford to be late. Yard supervisors were coming to him already, giving him anxious looks and asking politely about how things were at Toro Del Fuego.

Just that moment his secretary opened the polished oak door. He heard the distinctive creak it made and knew what was coming. Another supervisor!

Julio groaned and, putting on a gracious smile, turned to received him.

He was surprised. It was his secretary holding out some tickets.

He shook his head and gave out a hearty laugh.

"You know everything that's needed before we call for it!"

The silvery-haired woman with the hooked Hapsburg nose shrugged. "That's my job. What if Senor Julio San Giovanni de Irazusta of Toro Del Fuego had to wait a day to go to Britain once he decided. Some business we would have then!"

She was right. He took the tickets, stuffed them in his pocket, and after a last look around scooted out the door.

Modern Transport had progressed to the point that Cherbourg, France, to Swansea, Wales, involved only a three hour hop across the Channel by boat. Bilbao had boats. It built plenty of them for shipping lines from all over the world. It also made the steel that went into them. But one thing it lacked. Not brains, not brawn, not boats and steel--but coking coal.

He knew his Welsh suppliers. A letter would do no good. Phone calls would do no better. No, it was best to deal, man to man, on the problem. The coal was not arriving regularly, not since April. What could be holding them up? Welsh separatists? Wage disputes? Too much wine, women, Welsh poetry and song?

Julio was still pondering these questions as he got off at Swansea and walked on foot to the mining company's port offices of Llywelyn & Rees, Ltd. Surprised at the big flags draped across the top of the building--all displaying Wales’ fierce Red/White Dragon--he went in.

Clerks nodded to him as he went to the back offices. They all knew him--or at least recalled the young man his father had brought over to break in with his suppliers.

The secretary, after a word with her, went away and came back almost immediately. She held open a door and he went in.

A portly, short but dignified man in a dark suit rose from his chair with extended hand and a broad smile.

"Mr. Julio--er, Irazusta? Of course! Irazusta. How is your grandfather doing these days?"

"Father," Julio corrected him gently. "And he is fine. His feet are bad, but his heart and mind are hale. He insists on working every day as usual, just as he worked when he was my age."

The company manager chuckled. "Oh, I can guess he'd do precisely that! He was all starch and business when we last saw him on these premises--wouldn't expect him to quietly fade away, now would we?"

The manager motioned him to sit down. The secretary came in and stood.

The manager glanced at her, then Julio.

"Would you like coffee or tea? And do you use cream? sugar? and something even more Welsh in it to get your manhood jumping like a fresh daisy?"

Julio was young. He was maybe too brusque where business and getting his steel to shipyards was concerned.

"No, thank you. I've come to see about a certain delay in the shipments we've ordered for the year."

"I'll have my usual, without ice, darlin’" said the manager to the secretary, who bit her lower lip and went out, returning a moment later with a tall glass of dark, highly viscose liquid that looked as if it could lubricate the joints of a lorry.

He turned to Julio as soon as he had a deep sip.

"Now, to business! Yes, about that delay. It's come to my attention as well. Usually, they conspire to keep me from knowing these things, but I have my own men to get the information I want. You see, Mr. Irazusta, just because I have workers, I can't always assume they are working for me. Sometimes I actually find they are working against me for reasons of their own."

He sighed and threw up his hands.

"But you know all about these things. Human nature, Welsh manhood being what it is, behaves the same--"

Julio's look must have shown that he wasn't buying human nature at the moment, just plain, old Welsh coking coal. He leaned forward to the manager and gave him an intent look.

"We must get the shipments, and they simply must be on schedule--not a day sooner, not a day later. Can you manage that?"

The manager blew out a gust of air and swung his head about in his tight collar. He rose and went to the window, which gave him a view of the docks and shipping. He turned back to the waiting Julio and his eyes were no longer so genial.

"I really wish I could, sir, but--"

The manager held out his hands as if the matter were out of his control.

Julio rose.

"I know I must dig a little deeper then. Maybe closer to the seam. You've been very kind. Now good day!"

He strode right past the secretary, who jumped up as he passed.

"How impolite these Basques are, not like the Castilians and Catalonians!" she said to the manager a moment later. "Hardly civilized, walking out on you like that? I have never seen such a demonstration of--" She would have liked to use the term, "male chauvinism," but thought her job was worth an ounce of discretion.

The manager sighed and sat back down, glass in hand.

"Never mind the boy! Let him try and fix whatever's wrong with them. I've had enough of it! Don't you think, dear?"

The "dear" looked at him as if she had not heard, pulled the door shut and went back to her tabloid Daily Mail coverage of the coming Investiture of a new Prince of Wales and the latest exposures of his secret love life.

Two days from the meeting in Swansea with the company chairman, the matter was fixed. or, at least it was resolved, with some chance of the coal getting back on schedule in the near future.

Julio walked away from the mine office with one of the officials who was showing him to the company car that brought him.

Julio stopped at the vintage Bentley, then took a few steps back away.

"I'll be taking you back, sir!"

Julio considered the man and his offer. Though it had taken him there, he had never really seen the country. He had been to Wales only once before, and his grandfather saw that it was all business. Perhaps this was his chance. His feet were good. Why not?

"No, thank you," he said, giving his gracious smile and handshake. "I need to put my Basque feet on real earth. It will do me good."

"But it's many a mile to Caer yn Arfon--"

Julio, shaking his head at the odd Welsh pronunciation and smiling, set off the good Basque way, so he could see the country for himself, breathing the unfettered air, soaking in the life-giving sun, treading the good solid earth with his excellent Basque feet. After a while, deep in the rolling hills and mountains, he was delighted seeing a lone pony rollicking through the grasses on a hilltop. How free! How unfettered! Surely, that was how a man's spirit was meant to be, created so by his Maker, he thought.

Dropping into town, he found a nice pub for a bite to eat, and the old-fashioned proprietess spoke Cofi, the local dialect, so he couldn't understand a word, but the seafood was excellent. She pointed out the window, toward the Menai Straits, and then to a framed picture she had, showing the old ruins of Segontium, the original Roman fort and city. He understood, and nodded he would like to see it, which he did, since the roads were impassible with traffic.

Standing in the excavated ruins, he read the plaques, inscribed in English as well as in Welsh. Julius Caesar had mentioned the area's resident British tribe, the Segontiaci, and later the Roman commander, Agricola, founded a fort at the estuary of the River Seiont, after conquering the Ordovices in 77-78 AD. Segontium was then connected via a Roman road to the legionary base at Chester. Emperor Septimius Severus later built a stone fort, replacing the wooden one. The Cohors I Sunicorum, a Roman legionary force levied from the Sunici of Gallia Belgica on the continent, had garrisoned the stone fort.

It was fine view across the straits, and on a clear day some claimed to see Ireland. He thought how this far northwest point of Wales, with its river and estuary, must have been a chief port in the old days for traffic between Ireland and Britain, from the very earliest times--and so the Romans--who always had a keen eye for strategic sites--had planted their standard there.

On leaving Caenarfon, after the bumper-to-bumper traffic thinned out, he could walk the center road without having to step into the ditch for some official's speeding limo every few yards.

The boat home at Swansea was waiting for him--as if by magic. He hopped on and thought how well the trip had gone as the ship crossed the Channel. His father, he knew, would be pleased to see he had handled the matter so professionally--and even more pleased when the coal came in on schedule.

If not, it was another trip back! And Julio was prepared to do it.

He stepped in the door of his family home and was suddenly confronted with aunts, uncles, cousins--all looking solemn as death. He pushed through and got to the parlor where his father sometimes lay, unwilling to make the climb up to his bed when his feet were worse than usual.

He found his mother, his two sisters, and more relatives. He found the "etcheko jaun," "master of the house" his father at last, a richly embroidered cloth over his face as a priest finished the last words of Extreme Unction.

Everyone crossed themselves, then the priest made motions to go. Most of the people went with him, leaving Julio, his mother, sisters, and some few widow mourners in dark robes.

His mother turned to him. Her expression was the same as he had always known it--she seemed aged, yet ageless--a mother's eternal face, solemn, all-knowing, all-accepting of her own frail offspring and its misdeeds and short-comings. She was a rock that nothing in life could ever overthrow.

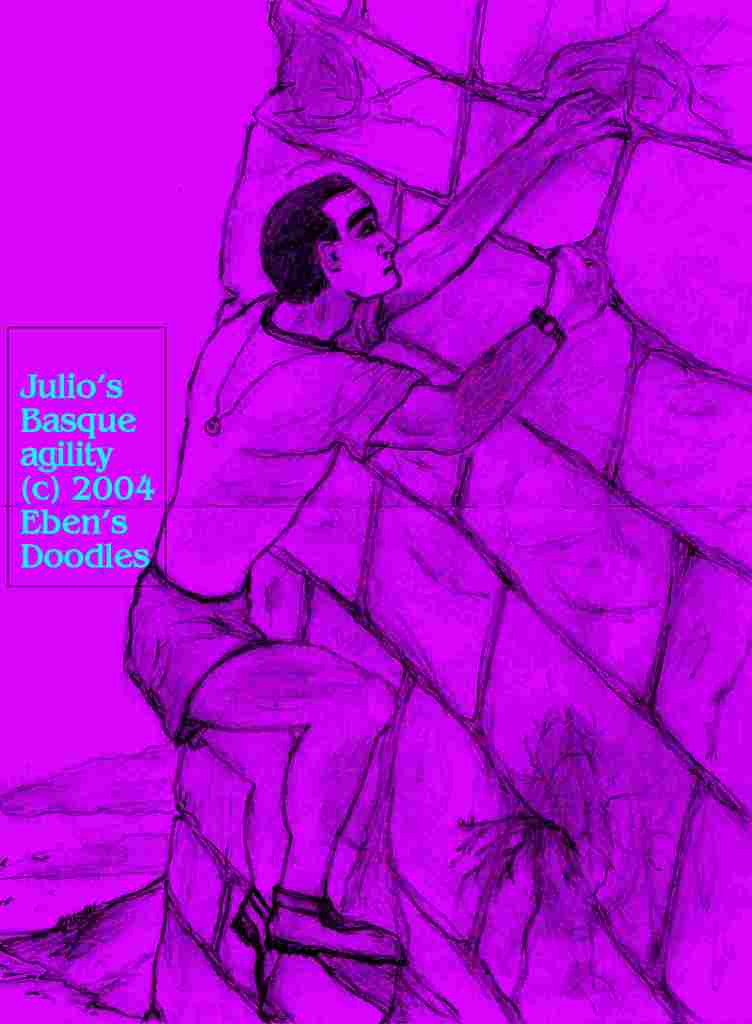

Later, though it had not bothered him before, Julio could not bear the thought of the workaday mill and all its noise and belching stacks. He escaped the day after the burial up into the mountains. It was the mountains that had birthed his people, not the easy life of the seacoast.

Climbing through thick bracken and craggy rocks, he felt the sharp edge of the wind and the drank in the warm sun and smelled the fragrances of fern and wild flower--it was the same! It had not changed, not for thousands of years. He had only been away a year from the mountains anyway--since his last dove hunt with his father.

He did not stop at the village but kept on until he reached a shepherd's hut named "Goizean Goiz," "early in the morning." There he rested until early the next day, though he felt little strain from the nearly vertical climb itself. He had brought some food, which he ate, then he went out to netting grounds running on the only level stretch in the pass, the "palombiere," or "place of doves."

Every year, for thousands of years, his people had gathered at such places, to hunt the delicious "utzo churia," the wood dove that flew from wintering grounds in Africa to Scandinavian refuges always by way of the mountains of Eskual Herria. No one knew why they came--they just came. It was out of the way, they could fly straight and avoid the loop eastward into Eskual Herria, but no one would think to tell the birds that.

He was just in time--old friends of his family greeted him--somehow they had heard, and he listened to their condolences. Though now, eldest and only son, he was the "etcheco jaun," it meant nothing at this moment compared to the loss that gave it to him. He nodded and lowered his eyes and let them go back to preparations for the hunt.

Finally, the nets were ready. It was time to climb to the Tower of Death, up to the hut constructed in the biggest tree.

No one would think to stop him. It was his right to do it. He made the climb with his third cousin, from the French side, Jean-Zalbador Luz from St. Jean-de-Luz.

It was time as soon as they got to the hut to look out for the wood doves and, sighted, throw the wooden paddles that, winging overhead, looked like falcons to the birds and drove them earthward, right into the waiting nets.

Julio could hardly breathe--it was the old excitement, older than Rome, older than Egypt and Assyria, even as old as the first Eskual Herria, the lost, Atlantean "White Land" some said. A longing for what was lost and impossible gripped him heart and soul. All over a little wild-dove!

But how beautiful and brave a sight they were! In years past, as a growing boy, he had climbed to the Tower of Death and waited there with his father for them. Then, in a flash, thousands were swooping past the tree, a cloud of beating wings. The hunters had to be fast to throw the paddles before they had swept past the nets.

They waited. They waited some more.

One, then two wood doves, flew by. A bunch of maybe a dozen also appeared, not stopping as they flew on toward the north.

Still, no birds. Not enough anyway to warrant throwing the falcon-paddles.

This had never happened before. What should they do?

With crushing disappointment on their faces, Julio and his relative finally climbed down to the waiting group at the base of the tree.

They all gazed skyward, no one saying anything--and Julio the most heart-broken and bewildered of all since he had failed to fulfill his father's last sacred wish.

Neither could ornithologists make anything out of it. The migration had failed somehow. Was it the changing weather pattern from temperate to sub-polar over much of the globe? Or pesticides? Or increased solar radiation levels, detected by scientists around the world?

For answers they would have to make expensive, difficult treks into the African interior, and that would require funding, probably government grants. When they did find the wood dove's wintering grounds, would they see anything but dead birds' feathers and bones? No one really wanted to go--and so no one did. It concerned, after all, only one avian species. Nothing irregular was happening to any others that they were monitoring.

So, as it happened, only the Basques, culturally tied to this particular bird since mankind first entered these mountains, waited for the doves' reappearance--as if their lives depended on it. But they waited in vain.

The world simply did not care enough to find out the true reason--why the wild wood-doves, unlike Capistrano's faithful flocks--did not return. But for the Basques it was something of a national tragedy--a sign that, here at least, the world had come somehow fatally unhinged, losing the linchpin at the center. Troubadours, the "bertsolari," expressed the heart cry of the people when they began to sing, competing with one another in rapidly improvised verse. They began with the well-known "Song of the Wood Dove" and went on from there in dialog between bird and fowler as old as human memory, perhaps.

From my country I departed with the thought of seeing Spain. I flew as far as the Pyrenees, and there I lost my green youth and sorrow overwhelmed spirit.

But white dove, white dove! You have not come to our mountains.

Where have you flown away? Our hearts are broken each day you do not fly in our land! We will die if you do not come again to us!

I cannot help it. I lost my green youth and sorrow overwhelmed spirit.

This year the crystal broke, in dance after dance, just as it had broken in 1945, upsetting the host particularly, at Winston Churchill's bash for Truman and Djugashvilli at his Potsdam-Babelsberg villa.

The doctor came at once to the house of the Irazustas. He knew the family well, having attended the old man before his predictable demise as well as certifying the death.

"What is wrong with him? He no eat, no sleep, and now he no work! This is not like a young man! You must do something! I have a good village girl for him, and just the right gifts for him to take to her parents."

Dr. Baroja followed the distraught matriarch into the mansion and was shown to a small room at the rear. He knew his Basques well. They spent so little time in sleeping rooms, why make them anything big and special? Basque life was public and centered on the household kitchen, the taverna, and the village or town square, in that order.

Julio's monastic room held only a picture of the usual "Sacred Heart of Jesus," an iron Crucifix on the wall, a simple cot, and no rug on the daily-scrubbed wooden floor.

The mother waited at the door. There was no room for the three of them.

"My son," she called gently to the form turned away from them in a thin blanket. "I've brought Dr. Baroja. He wants to take a look at you. Please let him look at you, my son."

She turned away in tears and went into the hall, while Dr. Baroja stood and looked down at the unmoving Julio.

After a few moments, Julio shifted position and the blanket fell away from his face.

Dr. Baroja, even in the dim light of the single bulb hanging from the ceiling, was surprised by the emaciation. He had seen Julio at the father's bedside and it was a different Julio then--full of color, manly powers, and the famed Irazusta comeliness. This Julio he saw now lying with eyes closed looked more like one of the Spanish saints in El Greco--thin, other-worldly, ascetic to an extreme, all the fine bones showing.

Concerned, the doctor knelt and slowly, very gently, began his examination. Julio was a good patient, making no resistance as the doctor feared he might, though he did not respond to requests to move his limbs or sit up. Dr. Baroja had to test his reflexes where he lay.

The examination over, Dr. Baroja stood and looked down at his patient, only twenty one, at the apex of a man's greatest virility, strength, and beauty, yet betraying the certain signs of one hovering close to death.

He slowly shook his head. A tap at the door made him turn, and he saw Julio's mother, with her two daughters standing behind her in the shadows.

Mrs. Irazusta had a bowl with a steaming liquid on a tray with a spotless, embroidered cloth.

"Since you have cured him, he will need to eat something now, no?"

Dr. Baroja gave her a sad look and shook his head.

"I cannot do anything for him. There is nothing wrong with him! Nothing!"

He knew what her response would be, but he could not help it. It was the truth.

She was indignant to a point of fury--all her bafflement and fear coming down on his head, because there was none other she could pour it on besides her two daughters.

Though a most dignified, courteous matron, she motioned with a brusque gesture to get himself out into the hall, and then she turned on him.

The excellent broth, he noticed while she raged at him, was spilling on the cloth and the immaculately swept and polished wooden floor.

"You are worse than a Gypsy quack!" she cried in a furious low voice. "Give him an injection and get him off his bed! Why can't you do that? Did you do that? I call you here to do something. Then you say he is well, there is nothing wrong, when he lies there for two days now not moving, not speaking, not eating--?"

The tirade went on for an eternity, and the daughters shrank back, the doctor noticed. It was most unseemly for a woman to address him like that, though he knew very well he could not claim higher social standing than a mountain trail muleteer. But he understood--the prospect of losing both men in the family was too much and something had snapped. She would recover--in time. But for now there was nothing to help her--nothing except her religion, if she would only recall it.

But, her anger and bewilderment finding fewer and fewer words, she did recall after she put the tray down and her hand went to her neck. It seized on the crucifix she wore day and night and her eyes closed in intense pain. A moment later they opened and the madness was not so bright and terrible in her eyes as she gazed at him.

As for the soup, she remembered that too, and had her daughters help her clean up the floor immediately, while apologizing to the doctor for the inconvenience.

Julio continued to lie in his bed, sinking lower each day.

His mother could not see her only son die and do nothing more. She called in every doctor she could get to come, though some refused, having heard on the grapevine about the case.

As happens when no cause can be determined, extraordinary means were tried. Not because of her important position as mill owner's wife but due to most ancient ties of honor and dignity, Mrs. Irazusta's range of contacts was wide in the villages of the hinterland, and strange-looking, older women scurried in from places near and far--but mostly far, they said, getting an extra bonus from the mother. They plied the sick one with all manner of herbs and rich invocations of the Blessed Virgin, saints, sun, moon, stars, and, the old stand-by, the Zodiac.

Seeing no change for the better, the desperate parent packed them out of the house one day and turned to Science as a last resort. Though it was a new import to her thinking, therefore suspect as such things should be, some Basques had taken to it and done well enough, so she was willing to test the waters.

"Medicals are fools! All fools and quacks! And the old wise women, they are greedy for money--they are as ignorant but still they demand money which the quacks are ashamed to do. No, I want my boy to live! He must! I will get someone--maybe the Americans can help. They are so clever, those people. They can do anything. Let them save him!"

Having heard of American Space Science and Exploration from her daughters who were high school age and very good at studies, Mrs. Irazusta got an English-proficient operator and wired the National Academy of Physical Sciences in Huntington, California, appealing for help and describing Julio's symptoms. If one virtue typified the Basques, it was persistence against impossible odds--and Mrs. Irazusta was no exception to this.

She received a kindly composed and courteous letter. They could not help here, since the National Academy was not a medical research institution, but they referred her to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, John Hopkins in New York, the University of Washington, and other renowned medical research facilities.

She tore the letter up, then reassembled the pieces after getting an idea. With her daughters to assist with English, she sat down and wrote a long, difficult explanation of how “different” this case was.

Her brash idea worked. It was simple. She said that Julio was a particularly good case for science research since all medicine and doctors had failed. She added that she would be happy to pay the expenses of any scientific investigation into her son’s condition.

"A perfect, healthy man in his blossom cannot die from nothing!" she wrote. "He is struck down by the poison breath and dews of certain wicked influences from the stars! There have been cases before of that in our history, you know. This is a new case no doubt--but here it is in our Bilbao! He was out in the fields above the city, he went hunting, then he comes back and soon he no longer can work, can eat, can speak--he is a vegetable! It was not the bad cold wind, he was not shot by anyone--he is just the same son in his body but he is dying. No man can die without a sickness or a bullet! It is not scientifical!"

The crisis had revived an old memory. As a little girl she had listened, spell-bound, to a troubadour who had wandered in off the road to her village. He started singing while they were doing last chores and getting ready for a meal. It brought everyone outdoors to hear him, he was that good. Normally, being so young, she would not have paid anything but passing attention. Many such penniless troubadours toured the land year-round. Then everyone customarily sang unashamed in her homeland. It came as naturally as dancing to them.

Shepherds sang to the mountains and their flocks, school chums sang to each other, men in cafes sang to visitors from other lands. If they had an army, it would sing first to the other army before killing all of them. Then it would sing as it buried the invaders. It was a common thing. But this old man was different, his song was about an evil worm wandering the wide earth and doing what mischief it could.

The worm crawls in the bud, and eats the rose unseen; beware the worm, beware!

She gnaws the rose with teeth red and keen!

It was the greatest courtesy they could think to do him and his strange, malevolent Worm. Would the singer return? they wondered. But he never did. Perhaps he died of old age before he could find their village again. His village was supposed to be on the French side, though no one had heard of it by the name he gave. Somehow everything--old man, worm and the flashing-red teeth of it--came to mind when she was most desperate to save her son. It was a clear warning that "something" lurking hidden in the world was doing much mischief to man and beast.

Her English improving with each attempt, she wrote five letters more, each longer than its successor.

Finally, the National Academy had to agree with the amazingly persistent Basque woman--that her son's case was a bit unusual. A department supervisor got involved who wrote requesting medical diagnoses before he would do anything. Mrs. Irazusta sent a big cardboard box of them express airmail.

Weeks passed and there was not a word, then the telegram operator came running to the door from his motorcycle.

Haggard, her eyes red, half in grief for her lost son, Mrs. Irazusta answered, then took the telegram with a listless hand. She had no strength to read, and it was English. Her eldest daughter came out to look and saw the problem. As she read it took only a second or two for color to come back into the mother's face. She had her daughter read it again, then again.

Within minutes of the final reading, the Irazusta household was transformed. The three women were busy from then on, cleaning what was already clean, making ready for the coming of the two "astrophysicians," as they were called in the telegram. Since she had refused to move Julio, they were obliged to pay a visit.

"From Nay-Sah! I never heard of such a town! But they are wonderful experts!" the woman cried joyfully. "After all, they're Americans!"

"Mother, that is NASA," corrected her sixteen year old eldest who knew about acronyms. "National Airplane and Sailboat Arrangement! It sends up all their big moon rockets."

Her younger sister strongly objected, holding out "Aerosol" for the "A" and "Sanitary" for the "S", but even Madame Irazusta thought that far-fetched.

It did no good, she was fixed on Nah-Sah, some American city of experts that produced men who would cure her son of his mysterious but deadly malady!

NASA was coming! American rocket scientists! For a mother who had given up on all the medical and herbalist-soothsaying profession of Eskual Herria, what could be better?

The news of such strange happenings at the Irazustas soon swept through all the city. Crowds began moving slowly past the mansion, pushed along by gendarmes who were just as curious to see the "rocket scientist" guests, who they'd heard were going to build a solid steel spaceship in Bilbao--one that would take Basque volunteers to the Moon!

As soon as she had them safe inside from the mob pressing at the door, she started right in about the reason for their visit, her son's condition.

"Men do not fall sick for nothing! He cannot have a sickness, just as the doctors say though they do not know anything else! No, he goes up to hunt the wood doves, the thing we do every year. He comes down to die! But men do not get sick at hunting--it is good for the body and spirit! Very excellent! But no, he comes down to die! Surely, it is a thing the stars did to him--there is no other evil thing on earth to kill him like this!"

Her daughters interpreting for her, she poured out this and similar sentiments, while Drs. Hegel and Beckworth listened politely if not too closely.

Actually, they had been well briefed on the wealthy widow of a leading Bilbao industrialist, and did not mind giving her a few moments to express grief behaviors.

The actual exam was done quite properly, with the women removed. Exciting the crowd as each arcane item was uncrated, they brought in instruments and began running cable out to get more power.

Some of the more imaginative spectators speculated that the Irazusta house was to be a rocket launch pad, the first of many planned for Bilbao. People laughed, but as always happens some took it seriously and ran to tell others.

Busy as the visitors were, they sometimes had to comment on their unusual venue.

Hegel turned to Beckworth.

"Imagine how these Basques live here! This is one of the better houses, but there's no bathroom, no hot water, no--"

His colleague laughed as he worked on a last minute adaptation to a TSRG, or transponder sonar receptor graphopheme.

"That's par for this culture with its peculiar mix of the Iberian Stone Age and high technology! They're a most strange, austere-living people and, besides preferring absolute simplicity in their living arrangements, see nothing hygienic and civilized in having a place to relieve oneself in the same dwelling where human beings prepare food, eat, converse, and sleep. "

Beckworth recalled something from med school. "Why, if that isn't strange enough, some say they're the last of the Cro-Magnons, which I personally think is rubbish. They choose to be backward in some respects, but they're some of the most enterprising, productive, and adaptable people you can find. I've worked with a Basque or two on different projects, so I know. Wherever you find them, they seem to rake off more big grants and Nobel prizes than anybody else. But the last of the Cro-Magnons? Obviously, that's hogwash. Racial extinction is a sure sign of a lack of adaptation--intelligence, in a word. Basques, being so clever and vigorous, are not likely to be expire and fade away. That's what, to my mind, makes this case we're working on so interesting. By the way, I did a little research. This is the family--these Irazustas--that produced Ignatius Loyola and the Society of Jesus--perhaps the most learned body of teachers and scholars the world has ever known. Now that this family's no longer producing firebrands of scholarship and piety, they're turned to making some of the best steel in the world. What they turn to next is anyone's guess, but it will no doubt be something superior."

"Talk about rubbish, there's something even more ludicrous: the Atlantis connection!"

They had a good chuckle over that.

"But, Alvin Tarkington, " concluded Hegel in a more serious tone, "there is something authentically different about these people--beyond a cultural pre-conditioning against having flush toilets in their houses. I mean, there's been studies, by anthropologists and others, of blood groups, and the Iberian Basques have the lowest incidence in Europe of B blood group, a high in O blood group, and the highest known frequency world-wide of Rh-negative blood type. I can see where people got off on that Cro-Magnon and even that 'refugees from lost Atlantis' notion. Genetically, they are different from us. Genetically and culturally, they do march to a different drum and drummer."

Beckworth's smile faded. "But Kyle Otis--" he began, then said nothing more and suddenly found a million things to do.

The equipment, brought in a van from the Bilbao airport, was fully installed in the tiny room, with the hall being used for electric cables and even empty crates, which had to be brought in to save them from souvenir collectors outside the house. It was a tight squeeze, but they had the transponder, TSRG, encephalograph, X-ray, and everything else in place. They even had a radio receiver just in case NASA had an emergency and needed to get in touch.

Julio, all while this was going on, remained silent and comatose.

A curious priest got in despite Mrs. Irazusta's express order, and she had to stop him herself from going in to administer Last Rites.

After she had sent him packing, she and her daughters waited anxiously in a room down the hall, the closest the experts would allow.

They heard some strange noises--vaguely like chirping birds or bats at night, the men talking, then saying nothing for long periods, and then some machine making rapid "Zzzzt" sounds.

Before the machine had quit Dr. Hegel came out and motioned to the mother, who was continually looking out of the room, unable to sit quietly and wait.

He spoke very quietly, intensely, and kept blinking rapidly behind his thick lens.

A pencil clenched in his hands was being bent as he spoke.

Madame Irazusta jumped as it snapped.

"Odd, most odd! Of course we will take the data and run it through UNICOM back at the institute, but I can tell you something now--to relieve some of your strain of not knowing anything, Mrs. Irazusta."

She nearly collapsed as her eldest interpreted. Her daughters had to hold her slumping form as it dawned on her.

Huge tears slowly formed at the edges of her eyes.

"God has answered a poor mother's prayers! The Blessed Virgin--"

The scientist smiled, then quickly continued, as it to cover the rather gauche and melodramatic aspect of her response but actually to get things wrapped up faster if he could.

"No, Madame, you are getting a little ahead of the research process. We have no answer as yet--and perhaps it is outside our field altogether. It may be chiefly a matter for astrophysicists and radio astronomers. But the instruments seem to indicate that radio waves are being transmitted from his vicinity."

The mother looked bewildered as her daughter translated.

"'Vicinity'? We have no such vicinity here in my house!"

The astrophysician was most gentle in the trying moment. He explained carefully that he only meant that he had not excluded the possibility that her son was not the transmitter of the radio waves--he might just be in the area of the transmission.

This was no better, the mother was just as confused. Dr. Beckworth came slowly out of the room, his eyes dark and brooding. He motioned to his colleague.

They conferred for a few moments, and then Dr. Beckworth went back in to Julio's room.

"We'll be packing up soon and going," Dr. Hegel informed the family. "We've got sufficient data for a study and a computer analysis. You have been so kind to have us. We must thank you for the opportunity to visit your beautiful home and--"

Her eyes rolling back in their sockets, Mrs. Irazusta struggled to keep him.

"No, you must tell me what you mean. I must know what is killing Julio my beautiful son to a vegetable!"

Her agonized outburst carried from the Basque without translation, and the astrophysician glanced quickly toward Julio's room and then back at the mother.

"All right, I will explain what I can now to you," he said in a hushed voice, letting his airline tickets expire quietly in his pocket. "Please listen carefully, for I won't be putting this in writing. It could mean my career, my reputation! I'd be made a laughingstock!"

A tall man, he bent low to be able to speak so confidentially without his voice carrying to the sick room. His face was one great painful blush.

"Your son--I don't know how--is sending out a radio message. Something is causing his hydrogen atoms to vibrate and send out radio signals. Taken together, the signal is repeated, again and again. Always the same signal. It's carrying a code I'll have to give to our computers to decode. The pulse was strong, but gradually getting weaker as we monitored it. Your son, Mrs. Irazusta, is telling the stars something--you were right to say the stars were involved--they are! But obviously he can't keep transmitting like that--it's draining him. He'll die if he doesn't stop. Unfortunately, he probably wouldn't know what we're talking about. It's an unconscious thing he's doing, and he wouldn't understand if we asked him to stop. No, he wouldn’t understand at all!"

It is not known just what Mrs. Irazusta understood of Dr. Hegel's brave admission, for, in truth, she couldn’t tell a hydrogen atom from a heliotrope or geranium. Yet in days following their guests departure her daughters repeated their scientific prescription many times as best they remembered. Hearing it, she seemed to be satisfied to a degree. Though she knew and accepted that Julio was doomed, she sensed her vindication in the man's words. He had spoken to her in different way that she could not mistake--not politely while keeping back his own secret knowledge but openly, even to the point of shaming himself unprofessionally before her.

Even though she would later receive a polite letter from them, explaining that they had fully analyzed the "data" and arrived at no scientific explanation for her son's condition, she knew differently. Madame Irazusta was admirably composed when Julio died, the day after she received the letter. Her house once again full of priests and mourning relatives, she saw that everything was done properly. Everyone that saw her commended her steely manner--amazing in one who had so recently lost her husband after twenty three years of marriage and was left with two daughters to feed and clothe.

"Our fathers' most holy faith has brought us through this!" she told her daughters afterwards, speaking from a strange composite of triumphant faith, peasant shrewdness, and existentialist-like angst that was quintessentially Basque. "My heart was broken to smithers. I could not believe the priests' words any longer. There was no sense at all in them. Now I believe them, every word. It is God's mystery, why such things happen. Man knows nothing about it. We must simply believe, my daughters. We must simply believe."

With a little help from American science, it might be added, not to mention the considerable Irazustra fortune.

But her daughters, now fatherless and brotherless, showed they could grasp reality with belief as ably as she. Too rich to attract suitors of equal or better means, both applied themselves to running the mill. Though behind due to the Welsh, they soon had it back on schedule. That came as no surprise to them, since they were as Basque as any man around them and persisted--as their forebears had persisted with Carthage, Rome, Byzantium, and so on--until they got their way.

Unfortunately, specialized as Hegel and Beckworth were, they failed to note some previous deep-sea research that might have shed some light on their own inquiry into the "Irazusta case."

With their clearances they could have learned from 3C 295 (radio source 295 in the Third Cambridge Catalogue of Radio Sources) that the whole region round the site of a certain sunken luxury liner in the North Atlantic, including seabed and water, was transmitting a signal. It was the same wavelength and frequency, the same radio signature, as Julio Irazusta's in Eskual Herria.

The message? Always the same in the case of either the dying or the murdered:

Professor Davis Lattimer Detweiler’s dream of a colossal spectrometer--able to smash atoms and open up the subatomic world for scientific inspection--came true on Stanford University’s campus in the rolling, brown, celebrity-studded hills of Southern California. Built with the then unheard of price tag of 114 million, it did not tower into the clouds as it was pictured on Detweiler’s office wall. Instead, it lay half-buried, running two miles across campus, crossed at one point by a commuters’ expressway. At the end towered two cavernous concrete structures called End Stations A and B that housed the targets and several six million dollar spectrometers.

From start to finish a 4-inch copper pipe lay embedded in concrete, covered by giant klystons that pumped incredible microwave energies into the tube to speed the electrons along to the targets of various, chosen elements. Once an atom or its nucleus was struck, the spectrometers tracked the deflected particles for identification. Did the atom nucleus stop at protons and neutrons, or was there something even smaller? Project M, resulting in the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC), was built to help find an answer--if there was one.

Congress proved particularly reluctant to serve up so much lettuce. It was back in the early Sixties when the highly expensive NASA’s moon mission was the top priority.

Dr. Ulrich Von Chewn, project director and first head of SLAC, liked to remind his guests at later dinner parties what a rough time they had had in Washington making Professor Detweiler’s dream a stunning reality.

Invariably, he prefaced his anecdote with some description of a certain, peppery Dixiecrat with a typical fourth or sixth grade education, Hiram Boggs Smoot III. One of the enigmas of the American political process, he was chairman of the powerful House Appropriations Committee, the third member of the Smoot dynasty to hold that kingpin position. You had to meet and talk with such people or you couldn’t believe they existed in real life, he added. No caricature or political cartoon did them justice!

Von Chewn was good at aping speech patterns and nuances, particularly those of politicians. Everyone found it amusing, time after time.

It was so funny, in fact, Von Chewn himself had a difficult time keeping a straight face as he played the parts of the wily, homespun Smoot and the Stanford don in confrontation over the funding.

“Monster,” Von Chewn replied crisply.

“‘Maawwwnnn-sterrrr‘,” repeated Smoot, rolling the syllables round in his mouth. “Maawwn-AWWNNN-ster.”

He was working toward four syllables and at least two accents when Von Chewn slammed his briefcase against the table, derailing the congressman’s agenda temporarily.

Then the man who held the nation’s purse strings looked up at the ceiling. He was still gazing there when he continued the inquiry, showing Von Chewn only the whites of his eyes.

“You have a good memory for figures, congressman,” Von Chewn replied with enough frost in his voice to chill the Congo.

Smoot pressed on, his eyes slowly descending from the ceiling to a point just over Von Chewn’s head.

“Well, that’s all mighty fine and all, but my daddy--bless him--would have had a bit of trouble swallerin’ this big an amount, even if it was to put an extension on Jacob’s ladder. Why, if this don’t remind me of Farmer Littlejohn’s sow, Daisy Mae. She been his best breeder hawg, you unnerstand. A farmer takes a whale of pride in hawgs like that, or he ain’t much of a farmer, is he? Well, one fine day she up swallered four sacks of surgahbeet. Those beets were spoiled real bad and Farmer Littlejohn was fixin’ to plow them under that very day before they caused any trouble. He had just drug ‘em out next to the pigpen and set them up when he had to go do somthin’. Well, as I said, ol’ Daisy Mae beat him to the beets! And when she done took herself a nice drink to wash it down she done exploded. She blew like ten sticks of dynamite in mama’s banana cream pie, takin’ out the fence on the pen and part of the barn roof. My, didn’t poor, old Littlejohn have a fit. He was behind the barn at the time payin’ Mother Nature his respects, or he’d been in big trouble hisself. But Gussie Faye the good wife saw it all from her kitchen winder. Soon as she finished washing up the dishes, she tole him all she seen. You could hear him cussin’ that sow over in Sweetwater County, since all he could find of her afterwards were her trotters. Where oh where was he gonna find anudder hawg like her? It was a tarble loss, iny way you look at it. But next spring, wouldn’t anybody have guessed it, the whole dang field opposite the pigpen was planted. Nothin’ in rows, mind you, but best surgahbeet crop in three counties, they said! A stump preacher at a meetin’ out in Honeysuckle Bottoms even said it had to be a miracle, takin’ it as a sign of the coming Year of Jubilee!”

Now it was Von Chewn’s turn to roll his eyes toward the ceiling. He always assured his audience afterwards that he had come well prepared for Smoot’s pitiable attempt to stonewall science and particle physics research. Breeder hogs, sugar beets, and down-home country religion? What did they have to do with scientific research, indeed!

“Interesting story, though I don’t quite see the point. Now we won’t take any less than the stated amount. The project can’t be completed without adequate funding. I would like to make one thing clear. If you, sir, want to go down in the records as the man who put this country behind the Russians in

science--”

The reference to the Commies, admittedly, was a low blow--a shameless use of a red herring. Von Chewn said he only used his ultimate weapon when reason failed, as it always did when dealing with Congress. Usually, you had merely to tell people that a given project would tell much about how the Solar System was formed, and that was enough to stun them into respectful compliance.

Smoot’s eyes were fixed on Von Chewn’s tight-wired eyebrows by this time as he absorbed the full gravity of Von Chewn’s broadside.

Yet he hedged, one final time.

“But why are you fine professors so hot under the collar to build THAT big a monster? Tell me that. If it were smaller, she’d cost the guv’ment a whole lot less! No sir, we ain’t got that kind of money, not until we know ‘xactly what you’re goin’ find using this ‘monster,’ as ya’ll calls it!”

“Congressman,” Van Chewn snapped, “if I knew what we would find, we would not be proposing to build it!”

For the first time, they were meeting eye to eye. It was a little disconcerting to Dr. Chewn. The world-acclaimed educator and scientist thought he might be looking at another species, he saw so little intelligence he could identify with. But he wasn’t going to give way.

On his side, Smoot blinked slowly, showing utterly no emotion, but running a tongue over his teeth and maybe considering that he wasn’t going to get this phuddy duddie professor to back down without making a nasty little fuss in the high brow Yankee papers.

Well, they got the appropriation--the full amount--so Smoot must have stuck up a wet thumb sometime about then and seen the way the wind was blowing.

Naturally, the biggest hog at the trough, NASA, was really put out when the news broke, since they were used to getting more than anybody else. But the furor from Houston soon died down. They knew better than anybody the old Russian bugaboo trick never failed, and so far nobody had the nerve to secure it with a patent.

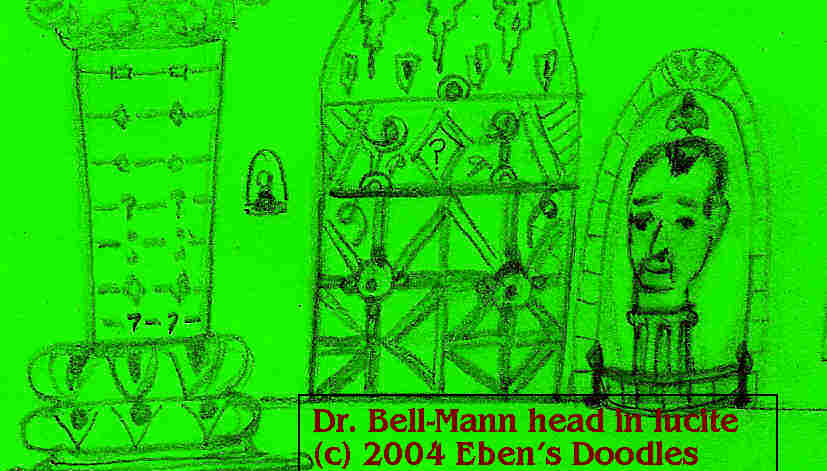

Protons and neutrons to leptons and photons, baryons, and mesons...SLAC kept firing at atoms, stripping the nucleus down, particle by particle, until it was getting irrefutable evidence for strangeness beyond anyone’s imagination--esoteric particles Nobel laureate Dr. Bell-Mann first called “quarks.”

In those glory days, Dr. Chewn was apt to tell worshipful, perspiring groups of postdocs and graduate students who did the heavy, dirty work of SLAC, that if the Honorable Smoot had got wind that they intended to look for things like quarks, it would have been the last project of theirs funded with him as committee chairman.

The showplace facility opened in 1967. Two years later the main effort was centered on pining down the existence of quarks, which many particle physicists, Bell-Mann among them, thought theoretical entities without actual material basis in nature.

All the SLAC people knew they would show Bell-Mann, sooner or later. Well, they showed him sooner than expected. Heads and busts of the great man and scientific luminary were already showing up in select venues. But so much renown can weigh unpleasantly on human beings who do not share it in equal part. It was beginning to grate on those who simultaneously worshipped him and contested his stand on quarks.

It was September 10, late in the first shift, when they were firing electrons at liquid hydrogen targets and striking something hard and tiny inside the proton. Christopher Columbus! They knew they were on the verge of a brave new world in particle research!

Looking casual but sweating profusely, McLeish retired to his work station and waited as the data came in, the whole facility suppressing wild excitement around him.

The next couple weeks they laboriously sifted and refined the data in preparation for the International Conference on High-Energy Physics (ICHE) held in Vienna, hoping to carry the day with their two “blue chip” quark confirmations. Their high hopes, however, were crushed when Bell-Mann’s supporters cut their scheduled talk to three minutes, hardly time to read the entire paper about the investigation and the results.

Dr. Chewn left off his sabbatical long enough to come read the paper, but since he hadn’t been in on the events and McLeish did not press the singularity of it, the SLAC director left off just when he was getting to the discovery of the first and then the second quark.

Instead of experiencing an avalanche of acclaim the international community of particle physicists recognized their signal achievement, Stanford’s SLAC people sat glumly in the shade while directors of old-fashioned bubble spectrometers held forth in interminable detail on their work.

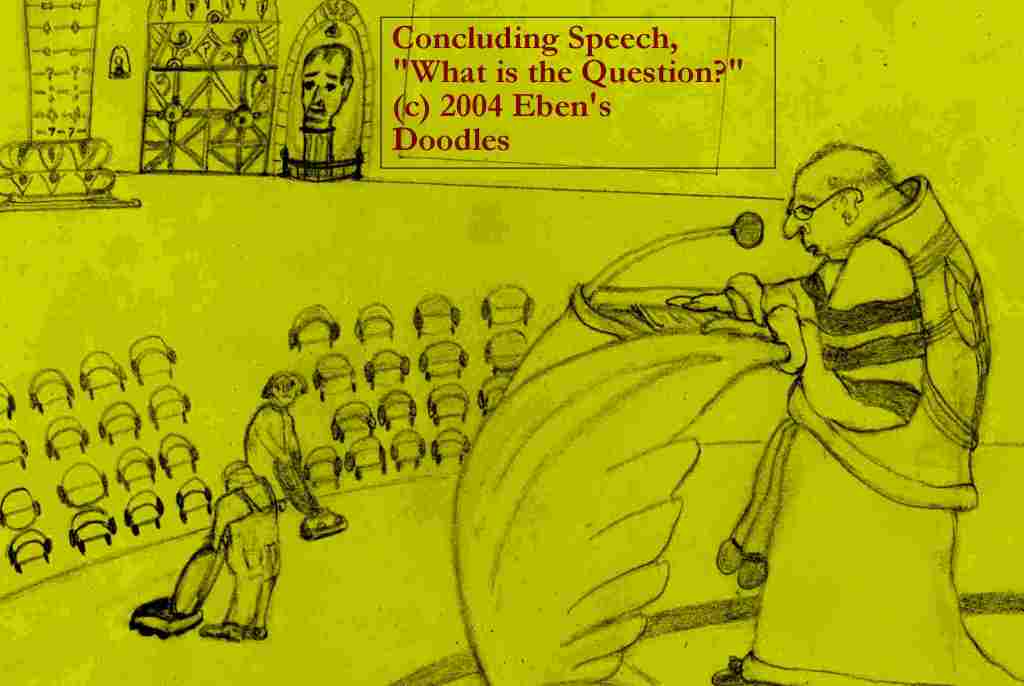

It was even further downhill from there. One of the bubble spectrometer people was speaking, and as he concluded he offered a personal aside. Nodding a wizened head, Dr. I. A. S. Godwin of Oxford’s Sacral Tincture College announced he was retiring from science, which had been his mother, father, brother, and sister for over fifty years now.

At this point people began to slip out. They weren’t being intentionally rude--this was physics, not “This is Your Life.”

Nonplused, the speaker continued in an octogenarian’s thin, quavering voice.

“Perhaps, it is rather bold of a fellow to address such a gathering as this with the cosmological and literary, but the late Miss Gertruda Steinway, American expatriate and patron of the arts in Paris between the wars, put it most succinctly when she said on her deathbed, ‘What is the Question?’”

Dr. Bell-Mann walked out. That did it. A horde followed, leaving about one third of the gathering still in their seats.

Dr. Godwin paused to take a sip of mineral water, then turned back to the ever-shrinking audience as he recovered his voice.

“Yes, what is the Question?” he repeated. “We specialists are trained too well to trot along one track, I think. We seek empirical evidence, then when we have it, we reach out in theory to encompass the Unknown, which we again seek to authenticate with more empirical evidence. By that manner we gain knowledge and control over the material Universe, it seems. But while we do that, are we asking the prime Question? If not, we are acting on the basis of the known, asking questions on the same foundation, presuming that we will someday make everything Unknown known--”

By this time the remnant of the audience was less than twenty souls, the others having left yawning.

Later, at a private party in a Hapsburgian grand-duke’s palace on the outskirts on Vienna, Dr. Bell-Mann was asked about the incident by someone who wished he might gain entrance into the great man’s confidence.

“Do we dare ask that kind of question in our field of study?” Bell-Mann laughed in response. “No, we have these daring, cyclopean atom-smashers in California to do that for us! Besides, we must remember what happened to the first person who reputedly asked it!”

Though he had led the way, theoretically, in the quest for quark particles, his remark, naturally, was taken for a polite put-down of the gung-ho Stanford quark people at the conference--those who really believed it existed and thought they had evidence for it.

Back at the venue of the ICHE lectures, the myopic Dr. Godwin was unaware he was speaking to janitorial personnel when he finished, saying with a flourish that threatened to topple the spectacles from his nose, “I for one wish before I expire to know what Question we should ask. Do you know it? I confess, I still do not!”

“I never dreamt in my philosophy that there would ever come a day I would be reading to my esteemed colleagues from this particular book. Please bear with me. I find it too much to the point to ignore at this time in my life and career. It says here in Psalm 71: ‘O God, thou hast taught me from my youth, and hitherto have I declared thy wondrous works. Now also when I am old and greyheaded, O God, forsake me not until I have shewed thy strength unto this generation and thy power to every one that is to come. Thy righteousness also, O God, is very high, who hast done great things; O God, who is like thee?’”

The aged physicist closed the book. His voice was a mere halting whisper.

“God help us, we may have slipped our moorings, ladies and gentlemen! What is the Question? Adieu!”

Dr. Godwin slowly gathered his papers, put them neatly in his battered briefcase, and shuffled out of the building, nodding to an imposing row of marble busts, Roman emperors and orators and philosophers he thought were faces of old colleagues and well-wishers gathered to see him off.

“What was that old gentleman jawin’ about anyway?” inquired a rail-thin, mop-wielding woman to a portly, sad-eyed broom-man. “I didn’t catch it--my ear gone numb on my right side, you know.”

“Sorry, madame, I don’t listen to these things--I just work here, minding my own business, if you don’t mind. It goes faster that way, I find.”

Returning to their duties at SLAC, the accelerator was fired up with a vengeance by the “quark people” under McLeish’s determined interim leadership. Grad students, they were "technocrats" first and human beings second--and were so dedicated to science and technology that the second category of their being was constantly forgotten. The media, stumbling and dragging cameras and cable through the wreckage, could not believe there was nobody dead. They kept looking for suitable fatalities until SLAC personnel broke out of the End Stations and met them. It was a stunning moment--almost like the survivors of the death camps meeting their GI liberators except that the liberated were in great shape.

“No, we’re all just fine!” Dr. Lonny McLeish cooly assured them. “It’s a miracle.”

“Cut!”

She went over to McLeish, shaking her head.

“You can’t say that on prime time, or we’ll lose our sponsors. Phrase it scientifically. Use some special scientific terms so they get the impression they’re getting something for their millions.”

“Okay. It’s an undifferentiated, unverifiable, anomalous situation here at Stanford. How’s that?”

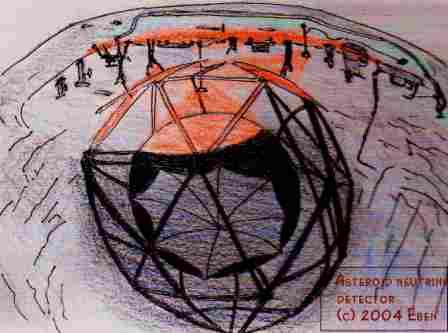

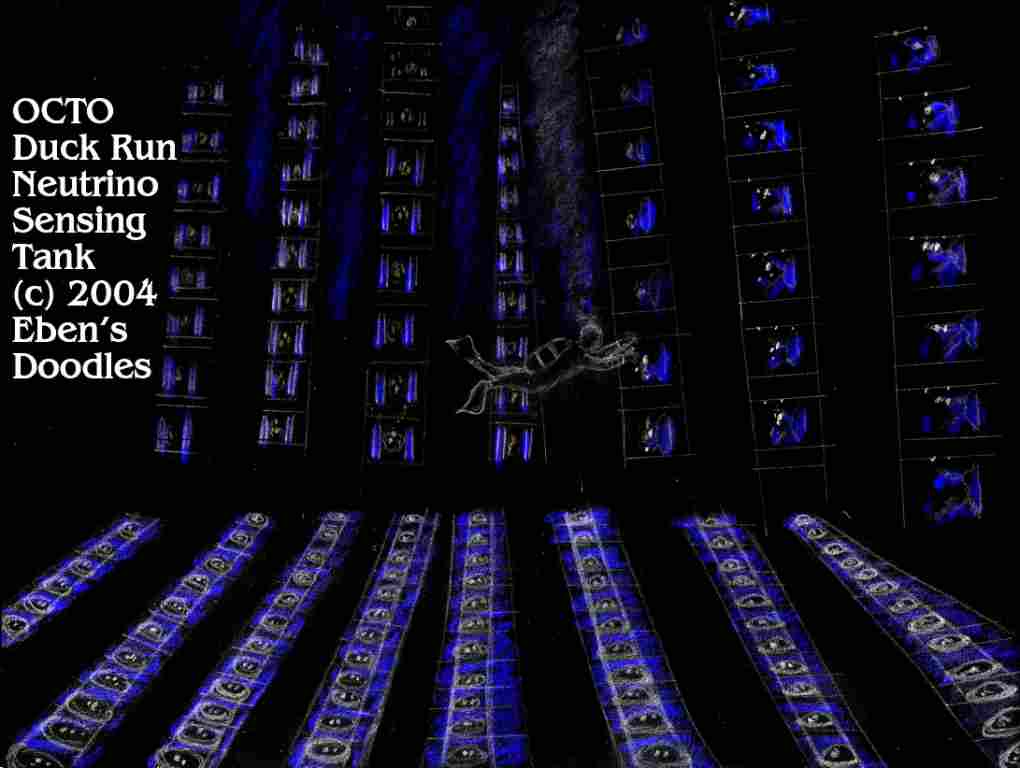

July 14. Two thousand feet down in an Ohio salt mine under Lake Erie, in a computer room next to a huge neutrino detector tank of 7,000 tons of ultrapure water and 2,048 sensors, University of Ohio-Catherine T. O'Culligan Foundation Neutrino Laboratory (OCTO) scientists and technicians worked hard to get ready for the coming test at 11:00 a.m. This was the fourth day of tests, forcing the rescheduling or outright elimination of others.

8:00 a.m. Graduate student Govindankutty Zair from Kerala, India, was in the changing room warming up for his dive when the OCTO CEO, Dr. Sardanapolous, came in.

Stripped to a white dhotis around his loins, Zair had just taken a few leaps and kicks from his repertoire of kalaripayattu. He flashed a smile and quickly bowed his head as he spun around to meet his superior.

"Good morning, Curtis," the director greeted him. "I just want you to know the well has run dry."

Everyone else had to call him by his Keralan name or he wouldn't answer.