Several years before Herr Shickelgruber’s brave new "Aryan" world order began to fall apart in equal part with the crumbling of his brain, a strange but telling incident occurred far from any real seat of power--an incident that presaged much to come, beyond even the end of the second world war.

He had hit upon the utility of doubling the vehicle’s specifications and its uniquely agile, independently motorized wheels as he was standing one day in a university tower. The window was open and the wind happened to be blowing hard from the countryside.

Though deep in thought, he nearly choked himself into an attack of apoplexy on an unmistakable aroma.

Though born and bred an urbanite, his mind seized on what anyone else would have dismissed with a slamming down of the window.

He saw that his design would have to be bigger, much bigger than the original five tons. After all, he had to account for farmer’s fences, barns and various other outbuildings on the direct, cross-country route from Chicago to Boston he had traced on the map. That meant the need for individual independent suspension and power for each of the wheels as well, if the Polar King was to surmount every obstacle and achieve notice as an engineering marvel. Immediately, he called a secretary and began dictating instructions for the wheel motors, struts, calipers, and suspension systems.

In a test run outside the city limits the Polar King performed beyond all expectation, crumpling barns, water tanks, and corn silos underfoot as if they were fallen autumn leaves. As far as he was concerned, he was doing civilization a favor by removing the rural infrastructure in order to make way for the urbanization that was inevitable, as Metropolitan America supplanted primitive Rural America. Farms would become obsolete and farmers a vanished species as factory farms took over the production of food for the masses. He looked at the open fields and the various methods used to cultivate and sow and reap harvests and saw only archaic and inefficient tradition that needed to be replaced by modern scientific agribusinesses. Of course, Dr. Poulett was visionary, but he believed he would live to see the eradication of farms and the shift of food production to the cities into enormous green-houses from which conveyer belts would transport their produce to the stores and the consumers. Earth would be liberated of the curse of an agriculture that had not changed fundamentally since the days of the Cave Man, as he viewed it. So anything he might do with his machine, Polar King, to hasten the agricultural revolution and the shift from countryside to city of food production was in his eyes his sacred duty, which a man of science such as himself might justly be proud of supporting.

Hastening to meet a scheduled rendezvous with the Admiral, the experimental craft churned to a halt deep in Ohio.

Already plagued by a series of unexpected malfunctions, Dr. Poulett's classroom-trained senses had sharpened and become unusually keen to detect anything that was not quite right.

He had been resting comfortably in his cabin when a mechanic knocked on his door. "A problem, sir, requires your attention," the man reported. "I'm sorry to disturb you, sir, but it may involve an inspection of the experimental vehicle's exterior."

The mechanic clicked his heels smartly, and went away, leaving Dr. Poulett to get himself ready.

A magazine some mechanic had left in the lounge, one his wife--a staunch Jehovah’s Witness having repented of her theosophical aberation under the tutelage of Madame Blavatsky in her earlier university days studying Mayan calendars and astrology-- would never have allowed in her house, slipped off his bed to the floor, drawing the doctor's somewhat guilty glance.

Since it was so beastly cold out, Dr. Poulett decided to slip into fur-lined high boots Mrs. Poulett had insisted he take along--just in case he had to go outside.

He was struggling into his boots when the National Geographic person--Fitweiler--Fitzhugh--something like that--caught him, a writing pad, pen, and camera at the ready.

"A BREAKDOWN, Sir?" said the wet, bare feet and legs (for the writer had dashed out of the shower to report the calamity).

"Nothing to be alarmed about!" Dr. Poulett informed him sharply without looking up. "Something needs a minor adjustment. A nut or bolt loosened up from the rough terrain we are crossing, I expect. You needn't write it up. There'll be plenty of epic things when we get to Boston--mayor, governor, New England Board of Trade, Boston Transit Authority, the Bi-Polar Exploratory Commission, the D.A.R. luncheon, and so on. Now if you will excuse me?"

Fitz-something taken care of, the professor hesitated at the door. It was so comfortable in the Polar King--quite as toasty as his own den at home on the North Shore, Chicago. They even had a gas-lit log in the lounge to raise morale and make it seem more like home away from home.

Once he had forced himself outdoors in the rude local elements, there was so much ice on the steps down he slipped and nearly fell to the ground. The wind was brisk too--flapping the flag on the Polar King so furiously it was being torn to pieces.

Something--a red spark, perhaps--whizzed across his line of vision. It was so sudden he did not see where it might have hit.

He didn't take much of a look around. The Chicago born and bred professor with the wealthy socialite, theosophical-Jehovah's Witness wife loathed rural scenery--and Ohio was probably just a lot of barren corn fields, oak trees here and there, cow barns pigsties and farm houses. As for the red spark--it was gone, as quickly as it had appeared.

Perhaps, he was imagining things, he decided. He knew it sometimes happened that a tiny capillary bursting in the eye can cause red flashes of the type he had seen.

Had his wife packed his eye drops? he wondered. He would have to look for them at first opportunity.

His breath frosting his glasses and blinding him, he floundered through drifted snow and made a quick inspection. From the sound of it, something had given way in the drive shaft, he decided. He determined the vehicle would have to be raised and the shaft repaired--and quickly too, lest the Polar King fail to get to Boston in time for Admiral Byrd's November sailing.

Pulling a ten-foot tire off a 235 ton vehicle was not easy, even with teams of men and horses. They had done that several times already--since in crossing hundreds of farmsteads the drive shaft had clogged several times with splintered lumber, boulders, huge masses of gummy manure, and even trees. But repairing the drive shaft?

Unable to fathom what they had in their midst, Gomer's friendly farmers offered a plenitude of oxen and horses. The first curious farmer on the scene ran off and spread the news. Before an hour had passed, the whole countryside had gathered in force to either assist or watch Modern Science and Technology at work and at close hand..

First, eager to give a little assistance to Modern Science and Technology, they hauled the Polar King to a small hill off the road. Getting it up with logs, winches, and brute muscle power, they next dug beneath and reinforced the hole with logs. Now they could clear and do any work needed on the drive shaft.

His mechanics assisting, Dr. Poulett supervised the repairs--an unmistakable figure in the group due to his orange rubber hip boots and white chief engineer's helmet.

Fortunately, the Polar King carried a repair shop and all the necessary tools, including welding equipment, besides a darkroom, galley, berths for four, lounge and control cab. In a real pinch, they even had the option of a Sparrowhawk, since the smooth roof of the giant was ideal for carrying small planes.

The crowd, drawing from as far as Attica, continued to grow in size. Bonfires were started up for warming the public. Some enterprising Gomer merchants even set up booths and were selling hot coffee, cocoa, and doughnuts (Get three glazed doughnuts for the price of two!).

While the people cheered the men on, some husky farm boys carried the little Sparrowhawk over to a level field and it was put in the air. Circling with a long banner proclaiming Admiral Byrd's expedition, the pilot dropped Pullman Company and Goodyear Tire leaflets, gum drops as large as cough lozenges stamped “Polar King, So. Pole Exp., 1939, ” and little American flags. It was a wonderful show, and the spectators didn't go away disappointed, especially those lucky enough to get a flag or gum drop. These same country people hadn't been able to afford going to the New York World's Fair, so this was, beyond doubt, a consolation prize of a sort.

The work went on round the clock, spotlights illuminating the spectacle.

Later the next morning, back on the route, Polar King proceeded across Gomer, flattening the downtown, on toward Boston, where three of the tires would blow out on the iron steeples of local churches, creating the biggest jam-up of traffic in the city's history.

Dr. Poulett was vastly relieved, even amidst the monumental snarl. Everything that could go wrong had done so. The steering wheel had gone to pieces in his hands, but thanks to American engineering genius and know-how Polar King was fixed and they were on time for the expedition.

Returning to Chicago on the train alone--his mechanics fired and sent off without pay or compensation--the professor found time to reflect on the venture, particularly the failed drive shaft.

It was the queerest thing he had observed in his entire professional career, and he had absolutely no scientific explanation. A degenerative disease for machinery? It made no sense at all.

Just as queer, a fragment of poetry came to mind as he was crawling into bed in his plush, private Pullman car--

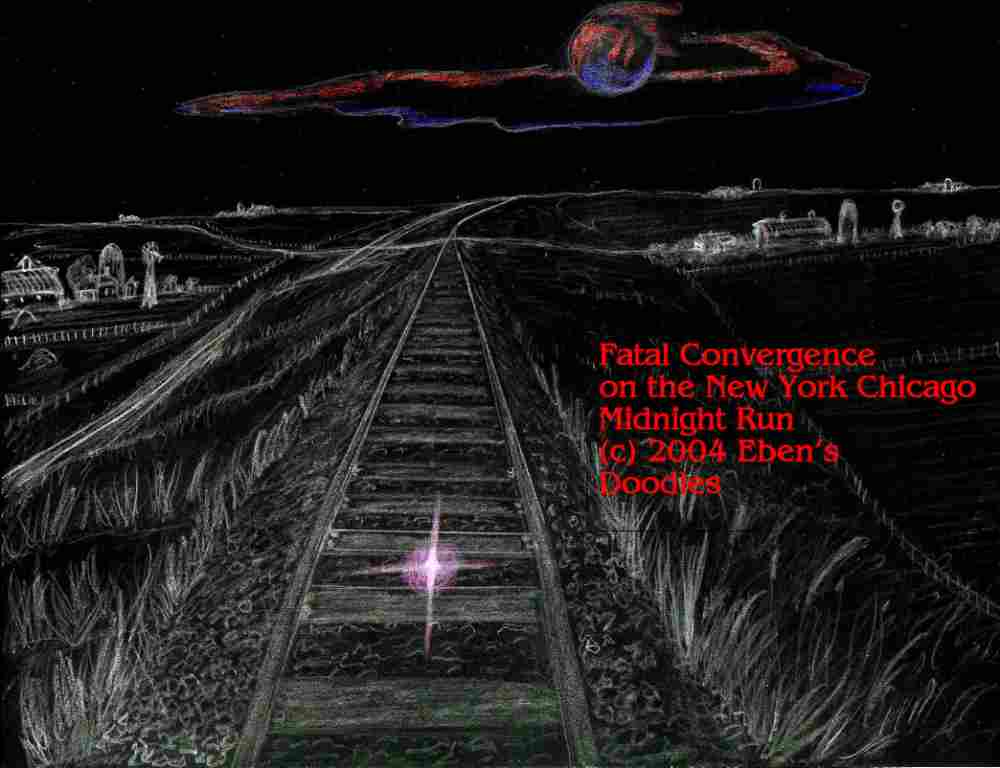

The crack New York-Chicago Express was speeding on toward the same terrain that Dr. Poulett had so recently devastated with the Polar King when a red gleaming spark buzzed down onto the tracks out of the night sky.

Thundering down the rails, the spankingly up-to-date, gleaming diesel locomotive's engineers never actually saw what they hit at nearly 90 miles an hour.

Later, inspectors on the scene tried to make sense of the accident as they surveyed the tangled, smoking wreckage. Somehow the train had contacted something head-on, crushing and compressing the locomotive all the way back to the cab.

They had one big problem: there was nothing on the tracks that could possibly have stopped the train and flattened the engine like a tin can.

Dr. Poulett was found with one hand clenched on a half-shattered blue bottle of Milk of Magnesia. He was but one of those covered with an army blanket while men struggled to get trapped passengers out of the other cars before fire made it impossible.

Polar King went on without its creator and was transported to Antarctica by Admiral Byrd. Unloaded from the ship, it started for the base near the shore but soon ground to a halt, the cyclopean wheels spinning uselessly. Was it the drive shaft again?

By this time, no one wanted to take the time and effort to find out. Poulett’s marvel of engineering genius was abandoned on the spot.

Admiral Byrd went on with this expedition, slugging it out to the South Pole without the comforts and glamour of the world-famed Polar King. When the last of his expedition would depart Antarctica in 1941--all personnel evacuated due to World War II--a huge mound of ice and snow marked the cairn of the Polar King, seemingly abandoned but actually awaiting a stranger fate than its creator could have ever imagined.

Things move rather quickly in the subatomic world. While Corporal Shickelgruber’s visions were being made stark and brutal reality after seizing the helm of German aspiration, equally momentous decisions were made in less then ten trillionths of a trillionth of a second--decisions that affected whole galaxies, not to mention minor solar system’s like one in which the alien had currently taken up residence. Having gathered data and experience for several decades, it had determined that the mainspring of the human civilization was not necessarily science and technology, nor was it even production of food and shelter. Beyond question, entertainment in its various manifestations was vastly more important. Once that was decided, implementation followed faster than light.

Dressed in a four-piece suit bought at a Woolworths department store sale, Clarence, his fastidious, knowledgeable, older brother, saw it and frowned.

“You might go a little easy on the syrup, it's pretty expensive here in Hollywood!" he advised this newcomer to the bright lights and the silver screen. “And you don’t want to look like a country hick with cow chips on his boots, do you? Some talent scout might be looking for extras or maybe they might be needing a sweeper on the sets to help clean up after a scene is shot, you know, only you still don’t know how to comb your hair and dress snappy enough to get jobs like that.”

While George watched quietly, Clarence took a fresh knife and fork and demonstrated how to slice pancakes properly like civilized city people.

“Hey, when’s your boat leaving from San Diego?” George asked a little sharply. "Are you going to let this apartment go, or let me have it since I'm staying on in town?"

"No way!" his brother laughed. "You're on your own, little brother! I let you come here--by the way, did anyone tell you I was here and could take in family members like this and feed and house them for nothing? There's the mission downtown Los Angeles, you know, if you can't take care of your own needs."

George bridled. "I'll pay you back, soon as I get the money from my first week on a job. Besides, you have the best location for me to find work from--without spending all my time and money on taking buses or hoofing or hitching a ride, which would take hours a day."

"Pardon me for asking, what job?" his brother sneered. "Counting your chickens, little brother, before they done hatched? How smart is that? I've been here quite some time, and it ain't gonna be as easy as you think getting on here, even in the movie business! Even with my looks, it hasn't happened, so what chances do you think you have?"

But what could he answer?

Following a tip on where agents could be found, he still hadn’t seen any in the IT cafe on Vine Street, though the women all were interested, he could not help noticing, staring particularly at his long legs and cowboy boots.

But women could wait until he had established his career! And old Clarence himself was barking up the wrong tree anyway, as far as coming to Hollywood, he knew. Clarence hadn’t landed any job in the movies, though he’d been in town over four years sponging off his sister whose husband had a good job as maintenance man at Warner’s. But he would succeed where his know-it-all brother had not!

Growing up on Montana ranches and knowing how to ride horse and herd cattle had toughened him, given him gritty, manly experiences he hoped to cash in on as a Hollywood extra or stuntman. Besides, the girls back home all said he was better on the eye than Gary Cooper and would be sure to make it in Western movies.

While Clarence rattled out departure time, endless ship statistics, and the various points of call of the itinerary all the way to Rio, interspersing his dry-as-dust account with brotherly counsel, George ignored big brother's advice and stuffed down more buttermilk pancakes, Montana-style. He thought hard about the tip he had about M-G-M hiring professional horsemen for the filming of Messiah. He knew it would put quite a feather in his bonnet if he could land a spot, even as a stuntman, in a major production about Caesar and Pontius Pilate and Greta Garbo and Charles Boyer. Talk about legendary screen stars--they were the king and queen of Hollywood, succeeding Douglass Fairbanks and Mary Pickford!

Imagine, appearing with them! The biggest names in moviedom! And being paid thirty five bucks a day--the standard pay for stuntmen which was more than most people made in a week!!

As soon as he could do it without being too rude, he shook hands with Clarence, wished him good-luck in the tropics and threw down a quarter to cover his share of the pancakes' cost.

“What’s the hurry?” said Clarence, dumping his milk as he rose from the table. "I still gotta lot to tell you on how to make it here. I don't wanna a brother of mine walking home, starving and in rags--what would people say if our names were associated?"

“Sorry, no time, gonna hitch my wagon to a star while there's still one in the sky!” George said under his breath as he beat it from Clarence's forty bucks a month two-room "studio apartment" and hoofed it toward the studio down an avenue of towering palms.

Let him have his sweaty, low-pay engineering job and putting up dams in some armpit of the Amazon! thought the aspiring cowboy as he flew toward a much grander destiny he somehow knew was his for the asking.

George saw immediately that his stars were just right that day. Everything was falling in place for him. While his brother’s boat was chugging out to Green Hells along the Amazon, his was docking at the white sugar cake studios of Metro Goldwyn Mayer!!

Someone asked if he could ride and after being sent to Wardrobe and Makeup he was on horseback, attired as a Roman cavalryman, waiting for the cue to ride alongside Charles Boyer and chariot in his role of Pilate the Roman governor.

There was a delay, however, which came as a surrise to George, who expected the movie business ran like clockwork all the time.

M-G-M had recently finished another production on the same set it had leased from Republic Films, which wasn't doing as well these days as its rival. To make room for the chariot and horsemen scene, the remnants of a Polish palace had to be cleared away. The last prop was some snowy entrance steps of the palace where a big ball had just been staged for the Emperor Napoleon and his lady love, the Polish countess played by Miss Garbo.

There was a lot of good-natured banter as the highly-paid maintenance men worked removing the grand staircase--it was not real stonework, but the thing had been built extra sturdy to accommodate a crowd of fake nobility going to and fro just before a mob of starving, poor peasants stormed the palace.

Finally, after a half an hour, the set was cleared for the change-over. Extra black canvas was laid over the labyrinth of cables and electric line, protecting the improvised electrical system from the horses’ stomping hooves. Laborers trucked in loads of sand and fake bushes and rocks and an old Jewess dressed in widow’s weeds. George was amazed at the quickness of the set-up. From marble and gilt statues of a palace entrance to some barren, dusty country road in Galilee, it took only minutes with everybody hustling to do his part. Truly, in George's eyes it was the work of wizards!

Mounted, George and his cohorts and the lone Jewish pedestrian waited for Mr. Boyer to come ride the golden Roman chariot.

They waited some more for Mr. Boyer. They waited, and then they waited some more. Dismounting, George pulled on his coat, more than a little embarrassed by his highly uncomfortable "Roman" uniform, which not only stuck into his flesh but featured a metal breastplate with the hideous face of a woman with snake like hair. Someone said it was "Medusa," somebody who could turn people to stone with a single look. That made him hate his costume all the more. What would his buddies in Montana think if they could see him fitted out like that, and with a skirt like thing that hardly covered his upper thighs? It made him cringe, but he tried to think about the money he was making.

Finally, the Old Jewish Widow scheduled for the same scene came over to George. Tired of the wait, she slipped out a rhinestoned cigarette case that was missing some rhinestones and had some gum stuck on to hold the rest.

Actually, she was just standing in for Miss Lilian Gish in a minor scene requiring no acting and speaking ability.

“Gotta light, big boy?” she smiled, her smoke held up in yellowed, trembling fingers.

George had no desire to be her “cookie.” He gave her a doubtful glance.

No, George didn’t know any such "dame," and his expression showed it.

He glanced quickly around. He knew the rules in an highly flammable setting, even if he hadn’t been there more than two hours.

He took her cigarette, hurriedly lit it with matches he carried only for lighting campfires, and handed it back like it was burning him. Then he mounted his horse, to let anyone looking his way know he was there to work, not socialize with women.

“Gee thanks, two things I never forget--a good looking man who tucks me in at night, and any favor done me,” the woman sighed and took a deep drag. “Not that I have much to remember in those categories these days--don't you know!”

She squinted and took a sharp look at him with her left eye.

“But I don’t believe in counting yesterday's chickens. Always looking ahead to better things--that’s me! Scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours--that’s the way I operate in this racket.”

George, hoping he wouldn’t get fired for helping her break the rules, didn’t know what to say.

She leaned against his horse, looking up and blowing smoke at him, Bette Davis style.

"Oh, so you’re the big, strong, silent type," she said. “I always kinda liked a man like that myself. I don’t mind doin’ the talking for both us. Hahaha!”

Her laughing turned to coughing. When she had recovered, she continued the conversation, which was really a monologue.

She then told him she wasn’t always playing two bit parts like this one. Not long ago she was a real hit in the Follies. In fact, she could sing and dance so well she had caught Mr. Ziegfeld's eye (or so a girlfriend told her) and was in line for front billing, except that the star who wasn’t feeling so well got recovered in time to go on. So she missed her chance of stardom by just a hair on a goat's behind and was stuck with carrying that big welcome sign! But now she had hopes for doing right by her talents in the movies. As for Mr. Ziegfeld, he could just go and fly a kite! She didn't need him any more!

The old show girl lifted her dark, ragged robe all the way this time, as this was no teaser. That showed black nylons emblazoned with sequined stars on what looked like a wicked pair of scissors, not human legs at all.

“Real killers, ain’t they?” she laughed up at George. “I can still shake a leg with the best of them--that hoity-toity Garbo broad included! What does old Sweden got over me anyhow? That snooty broad got no breasts as good as mine, and that phony accent--I heard better at the pizzeria! Ever since I was discovered in Toledo by Florenz’s agent--I was a hatcheck girl at the Claupwitz Harrison Arms Hotel, I been keeping myself in perfect trim for my big break, you bet. It’s gotta come. You can’t keep a girl like me down. That’s for sure, buster!"

As happens so often in the movie business, George, the other riders, and the ex-Ziegfeld hoofer never got the word--not that day, anyway. Instead, her cameo performance cut short, the smoker was sent sacked off the set, the moment an assistant producer found the time to give it to her.

“I’ll see my attorney!” she screamed back as she left. “I’ll see my union for this! Zelda Zimmerman ain’t goin’ to take the boot from anyone! ”

On another set, filmed while the old show girl was putting the make on young George, the strangest thing happened in this town where the stock and trade was the bizarre and mysterious.

Pilate and his beautiful wife Procula were having a spat over finances in the tower of the Antonio, his lavish, all-white Hollywood studio-style Jerusalem fortress overlooking the Jewish Temple.

Miss Garbo, attired in a classic Roman gown and simple but elegant gold jewelry, was confronting the governor, who was more heavily attired in golden mail and breastplate over a soldier’s short tunic.

Pilate, holding a letter of reprimand from Caesar’s current favorite, a commander of the Imperial Praetorian Guard named Sejanus, glared at his wife after he read and got the gist of it.

But Procula spoke as he started to protest his innocence.

“Always a governor, never a legate! Is that what you’re giving me after all my sacrifices? Why, you low bred-plebeian pig! You gutter dog! After what you’ve done, killing all those Galilean peasants after they objected to your raiding their Temple treasury! Is that the proper way to treat religious people? I’ll be gray-haired and toothless and tottering to my grave before you get another promotion from Sejan--er--Caesar!”

At this point in the script, the furious, defensive Pilate was supposed to crumple Sejanus’s abusive and threatening letter in his hand and then stalk off in high dudgeon.

He would have done so, completing the scene, but a jewel detached itself from somebody’s costume and flew past Miss Garbo’s shoulder, buzzed like a Kansas cicada, then shot right through the fake stone fortress wall without making a hole.

That was enough to end the filming, but nobody got a chance to do one thing more, for the set was suddenly plunged into darkness.

Though power outages were common due to the huge wattage required for Technicolor, darkness made everything grind to a halt, and there was chaos for several minutes before power was restored. Then they all saw they had a bigger problem than losing power.

How a full-blown, Old Kingdom pyramid ever got onto the lot was, for a few moments, beyond explanation. But there it was, rising up through the studio roof, utterly destroying the set and the day’s production schedule.

At least they thought it was a pyramid. It had the unmistakable triangular sides and pointed top, only it was shining with gold at the apex and gleaming white all the way down from there.

Predictably, Sam Goldwyn was furious at the costly delay in the filming and the need to rebuild both the Republic Films studio and the MESSIAH set's Roman fortress, though he was just as quick to capitalize on the pyramid and not to disagree when people blamed him for it.

Miss Garbo, report went out, wasn’t too pleased either. She told a friend of Miss Louella Parson’s that a red crystal of some sort flew by her shoulder, circled her and Charles, then the lights went out. Some people said it was ball lightning. Whatever it was, it made her feel very cold and very hot--a disagreeable experience! She concluded it was an omen of some sort--and Louella promptly put that remark down to a touch maybe of moody Scandinavian temperament in Hollywood’s greatest screen star.

Following up the Parson's article, WORLD magazine ran a story too, only it wasn't based on the interview so much as an imaginative celebrity reporter's attempt to go one better than Louella. An artist's make-over of Garbo's image appeared ont he cover, in Egyptian-style hair-style and jewelry.

The cover was a hit (the story was pure that a "certain Hollywood movie queen" was being plagued by ancient "mystery lights" released in an archeologist's opening of a Garbo-look-alike Egyptian queen's tomb was patently trash) and made the magazine a lot of money that issue--money they lost when Garbo sued for infringement of her right to her own face. It made no difference that the reporter and artist claimed it wasn't Garbo but a purely imaginative guess at how an Egyptian queen might look.

The eyes were set too far apart to be Garbo's, they added. To the judge they seemed close enough, and the magazine was docked one million. It seemed a foregone conclusion the WORLD would go bankrupt. A week later the same magazine made good its loss by a sensational article on a dead actor who couldn't sue them.

The marble, cigar-stained halls of another Tinsel Town, this one on Potomac, proved not so flexible in a crisis.

Corporal Shickelgruber’s bold move as German leader to re-annex the stolen Ruhr industrial complex had shaken things up a bit in London and Paris. In far-off America, a calmer mood prevailed. Things were proceeding quite as usual with long speeches in the Senate fulminating against “foreign entanglements” and “keeping America unstained from the quarrels of the Old World” when the venerable speaker, Senator Hiram Boggs Smoot of Tennessee, began quoting whole books non-stop of the speeches of Demosthenes, Cicero, Cato, and finally a “Limey,” Edmund Burke.

Senator Smoot couldn’t seem to help it, and as the filibustering continued for several hours the chamber could take no more and completely emptied, leaving the poor senator ranting and raving, and literally foaming at the mouth.

Even with his notable reserves of loquacity, Smoot collapsed finally from extreme exhaustion and was taken to the hospital. There he recovered enough to claim, with the press taking notes, that his mind was perfectly sound, thank ya’ll. He had lost control maybe, but it wasn’t his fault! Why, just before his mouth took off like that he was reading a prepared speech he written himself forty years ago when he was a greenhorn freshman in the House of Representatives. Then, suddenly, a red flash--like a humming bird-- whizzed in front of his face, fanning his nose hotter than a Cajun pickle.

Well, he went to swipe at it with one hand while going on with his speech and the next moment he found himself quoting some ancient Greek, then a Roman, and after that another Roman, and finally some Limey.

“Sir, exactly what caused you to lose--er--quote Greek and Roman orators for six or seven hours straight?” he was asked by a rookie reporter. “You demonstrated a most amazing memory for such an old--”

The sputtering, apoplectic senator nearly fell out of bed, he was so angry. He knew very well he even as a young sprout he couldn’t have memorized and put away any such amount of speecifying, particularly since he had only attained the fourth grade in a one-room school house.

“Why, confound you, I just said, it was that Cajun pickle, I mean, that red-flasher thingamabob!”

At that moment doctors entered the room and hustled the press out, before any more harm was done to their distinguished patient’s blood pressure.

It could do as it pleased with what the indigenous planetary organisms--or “human beings”-- called “technology and science.” Though they thought they were progressing, they didn’t know it, but they were on a leash. They could go only so far before it drew the strap tight like a hangman’s neck-stretcher.

A Skyhawk strike aircraft, being readied for launch at 1400 hours, rolled loose across the deck as the carrier was manhandled like a child's toy in a bathtub. Yelling to the full extent of his lungs, the newly assigned commander, Frank Turner, being nearest the Skyhawk, called for all those on deck for help, but everyone had been thrown flat on the deck and were clawing for handholds. Already at the edge, the Skyhawk teetered for a moment and then plunged off the high deck of the carrier.

Sirens started their climb up to ear-splitting decibels. Turner was first to scramble to his feet where he held onto some cable and run over to the edge of the deck. He got to see the Skyhawk’s wings fold and tear off in the impact, then tumble belly up as it washed rapidly away.

Everyone who could rushed to join Turner. There was nothing they or the captain could do. In seconds the carrier had left it in its wake, where the remnants wallowed and then took water and sank, nose down. Except for the still secret hydrogen bomb aboard, it was to have been a routine launch, like thousands of others involving Skyhawks and other strike aircraft in the United States' arsenal. Instead the worst thing imaginable in the history of the military had just happened--the loss of the H-Bomb, after a like disaster two decades early when a battleship carrying the secret death ray was torpedoed.

The commander grabbed an ensign's radio and reported to the captain on the bridge, then waited for orders. The carrier slowed and turned back toward the doomed Skyhawk. Nearly everyone aboard who knew what had happened was thinking the same thing: we lost the Bomb and our goose is cooked!

Finally, a terse command came down--"Commander Frank Turner, you are relieved of duty. Lieutenant Commander Hutchinson will take charge of your post immediately. Return to quarters, fill out your report, and we'll see what disposition is to be made."

The commander's eyes squeezed shut.

"Turner, you tore it this time! You really tore it!" he muttered under his breath as he ducked, head down, in a loping run off the deck toward his quarters.

In his room he locked the door and began to fill out the incident report. It was hard to control his unprofessional trembling, but exerting his will he thought he had it mastered until he tried to type the first word--then hit all the wrong letters. But that was the least of his problem. He sensed he would have to do a good job--report the facts, and not try to put in one word of defense--they'd be looking for any attempt to excuse himself and that would be the end of all his great career plans in the Navy.

Sweat was pouring, getting on the document. Tearing off his uniform and leaving only jockey shorts, he felt a little more relaxed and less shaken. He had just typed out the date, time, location, and nature of the accident on the report when the knocking on his door startled him so much he jumped up, nearly overturning the typewriter table.

He threw the door open, wondering at the same moment how long he had kept the major waiting.

The older man walked straight to his usual chair and sat.

Finally, after a few moments of silence which neither man wanted to be first to break, the major sighed and faced his young, inexperienced friend.

"It's a little stuffy in here. Let's go to my quarters. I've got something stashed away for occasions like this--"

Turner threw the major a glance of relief and, twenty minutes later, well into a bottle of sizzling bright Mexican sun and cactus, the shock of that day began to take a softer outline in Turner's mind.

"What would YOU put in the report?" Turner challenged his equable, easy-does-it friend with pain showing all too clearly in his eyes and strained voice.

Turner nearly dropped his glass as he stood, his face a stiff plaster mask that was beginning to crack, even as he tried to smile.

"Thanks. I was hoping you’d think of something better than that. He wouldn’t want to remember you now, right? I just know I have to get out of this the best way I can--but I was hoping."

The major stood, reaching out before the younger man. It was an open-palmed gesture, accompanied with a shrug, but Turner, who was trying hard not to beg, must have misunderstood.

"Lord, am I up a creek," Turner moaned. "Even you don't want to help me when I need it most!"

Turner turned away, his shoulders sagging in total, undisguised misery.

Shaken by the younger man’s plight to a degree he had not anticipated, the aging major had to sit down again. Turner threw himself on the major's bed and looked as though the world had come to an end.

The major brightened.

"I have an idea. It’s better than the admiral thing."

"What?" Turner laughed bitterly. "Transfer to the Air Force or Army after losing an H-bomb for the Navy? You think they’d take me as a Lieutenant Colonel and forget the whole thing? Fat chance of that! I’d be lucky if I didn’t end up washing pots and pans in some army depot on the backside of New Mexico."

The major laughed lightly, for he was sure of what he had to offer.

"Not quite so drastic. Rather, something that will work for you, I think, better than any attempt to rationalize the situation."

Turner sat up, his face showing a flicker of interest amidst the despair.

"Officially, what are hurricanes, earthquakes, floods, and volcanic explosions?" the major continued. "I mean, what do they all have in common that doesn't make them fit any normal context?"

Turner dumbly shook his head. "I dunno. I guess--I guess they are the same in that--well, they're not caused by man and are also far out of the ordinary, weather-wise."

The major laughed.

"You got it! If a disaster isn't manmade or a product of nature, it's an--"

Racing back to his quarters and getting his typewriter, Turner returned and installed himself at the major's desk. Quickly, he ran the page forward to the appropriate slot, and typed: "Act of God."

The moment that was accomplished Turner heaved a great sigh of relief.

Knowing his military history better than the young Turner, the major who had been around in his day told him he could take comfort. The disaster was not unparalleled, after all. Though Navy brass didn't like it turning into a topic of conversation, some tidbits still got around via the grapevine. He had heard about the loss of the ship in World War II involving the death ray superweapon, which had caused considerable alarm in Washington and the Pentagon, since it meant their only recourse with Imperial Japan was conventional warfare, thanks to the failure of the secret nuclear Manhattan Project.

"You see," observed the voice of experience , "these things can happen. To cope with similar situations developing and making fools of us again in the eyes of Washington, all sorts of preventive strategies were devised. Submersibles have been built to retrieve anything--bombs, subs, whole trapped crews--from depths up to 20,000 feet--a threshold assumed to cover any contingency. It took billions to pay for it all and buckets of sweat, military and civilian, yet all that can't--couldn't--keep it from happening again. It's just that the Navy thinks it's better prepared to deal with it now. Admirals like to get their sleep at night, but don't we all? Well, does that make you feel any better? You've been pretty quiet while I've been telling you all this."

"I've just thinking," responded Turner, half-believing he was going to come out--if not in the clear, at least with a chance to start over in some branch of government. "But what if the Skyhawk drops beyond 20,000--what then? There's supposed to be some really deep trench off the Azores you can sink the whole Navy in and you’d never find it."

It was a good question, and the commander paused to think it over.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy high command was just as dismayed by the news of the incident as it had been in the death ray case.

The carrier was ordered to glue itself to the site and make every effort to retrieve the aircraft and bomb, though it was even then rapidly sinking toward the depths of the abyss beneath.

Unknown to the major and his young friend in big trouble, within minutes it plummeted beyond reach of the most advanced bathyscaphs. As Turner feared it might be, the particular trench off the Azores registered 32,650 feet.

Then something occurred that further complicated the problem, ultimately taking the matter out of the hands of human beings, military and civilian.

The U.S. Navy high command and Admiral Dykinga who happened to be aboard his son’s Ticonderoga could only stand by and watch as yet another mind-boggling “Act of God” happened.

On a sea virtually without a ripple, the carrier rocked and leaned. It leaned some more. It finally leaned over to one degree past of the point of no return.

Just finishing the firewater Frank Turner had shared, the man who would never be promoted again in the modern Navy found the wall suddenly approaching his face. Then he was on the ceiling, crawling like some sort of human fly. He wasn't particularly alarmed. At first he thought it was just another episode of tequila rhapsody of the deep. It would wear off in time, he reflected.

He soon found he was mistaken.

Everything that had been riveted, bolted, or secured to bulkheads and floors--turbines, gun mountings, plumbing, aircraft, mess ovens, block-long rows of urinals and toilets, desks and lockers--began to tear loose as if all the rivets had sprung at the exact same instant.

The tower carrying the bridge, the captain, the admiral, and the half-painted head went overboard. The rest of the carrier followed and immediately sank into the same abyss that swallowed the Skyhawk and H-bomb without a trace.

A lid of secrecy was clamped on the event. Nothing appeared in the news and in the papers except report of an accident aboard the carrier resulting in some confirmed casualties. It was so air-tight a seal nothing of substance was leaked out until a lone Ticonderoga survivor claimed compensation for damages after almost three decades had passed.

Since he claimed reimbursement of several million dollars for injuries in the disaster, the Navy let the court in on reconnaissance information that showed no survivors. The case was thrown out once the Navy divulged that the only man officially known to be a survivor was AWOL at the time, dead drunk in a club in the last port of call, Buenos Aires, at the time of the capsizing

"It's all lies," the former Navyman told a reporter. "I can't fight them. They have too much money and power and a dozen lawyers on the case against me."

"But have you considered taking your appeal to the Supreme Court? After all, the Navy boys have smeared your reputation pretty badly, if what you say is true."

The man shook his grizzled head.

"I can't afford the appeal. And what good would that do? Those judges all hobnob with top Navy brass. I'm a nobody. Who listens to nobodies in this country?"

"You've got a point, " replied the reporter, growing restless. "I'm afraid I must be getting back. Well, good luck, Old Buddy!"

"Sure, thanks, Old Buddy."

"Hey, guys, I got a little project you can help me with, " Parks Commissioner Robert Moses said to the parks board at lunch at Delmonico's. "Gimme all your ages and I'll add them up. That should make a nice big figure for those egghead Westinghouse people who've been buggin' me! Just so it's not 7,000 A.D. or later. I'm--I mean, the Time Capsule, is NOT going to be upstaged by that dumb 1939'er."

Just to prove his point how dumb the 1939 New York World's Fair was, he had a somewhat faded fair poster passed round--though that wasn't exactly his point.

The ages were tallied, but Moses had underestimated his park board's longevity, which threatened to put him well beyond the cutoff year.

"What is this we have here, a VFW convention?" he roared. "Some of you ought to think of retirin' before your ivories fall out on your filet mignon!"

He was obliged to cut several of the more elderly entrants.

Founder of the projected 1969-1970 New York World's Fair, the greatest world's fair ever conceived by the mind of a genius, Moses was being hounded by Westinghouse for cooperation in making up the second Time Capsule. He had received a letter granting him the honor of naming the year for the opening of the capsule in some far future time and world. It was quickly followed a month later with a more urgent telegram requesting the date immediately.

Moses had objected to the tone of the telegram, sending it flying toward an overflowing waste basket. After all, didn't Westinghouse have a clew how busy he was?

"Time capsules are a total waste of time and bucks!" he ranted at his secretary, Miss Claricia Slocumb Renfrew. He could rant at her all he liked. She was his "executive secretary," which meant nobody else but nobody had her type a single word except her own private boss, the Parks Commissioner! And if she didn't like how he treated her, well, he'd boot her out and get somebody else who would. But Renfrew must ve understood the situation early on, for she had been with him longer than he cared to remember.

"The Commies will be throwin’ some secret Doomsday Bomb of theirs at us any day now, so none of us are going to be around in a thousand, much less 5,000 years, to see the junk in these things! Do you have any idea what they put in them? Well, a guy who helped construct the Trylon and Perisphere at the '39 World's Fair told me. That 1939 Time Capsule had, get this, an autographed script of a Greta Garbo-Charles Boyer movie, Buster Keaton playing chest-pounding, snortin’ Cave Man in “The Three Ages,” a recording of Joe Penner’s radio gags, Plymouth Rock chicken feathers, a package of Portland cement, a Mickey Mouse cup, DUTCHGIRL cleanser, brochures from major auto manufacturers and shop manuals for manufacturing the deluxe 1938 Packard Flower Car, Al Jolson in the first talkie, “The Jazz Singer,” belting out that old tear jerker of Stephen Foster’s, “The Old Folks at Home,” a model of Flash Gordon’s rocketship, Houdini's lock and chains from the East River stunt, and--and if you ask me, I think they should have filled the whole blasted thing with chicken feathers and saved themselves trouble!"

His attack of choler was understandable.

HE, the Parks Commisioner, was the man who had to decide everything. No one else, he knew, could be trusted, even with the details. So he was occupied night and day on the project, selecting locations for the Fountain of the Planets, the Tower of Light, the U.S. Space Park, the Belgian Waffle stand. It was virtually endless! Everyone was calling him, demanding to know things he still didn't know--such as where the U.S. Pavilion, New York State "Tent of Tomorrow," and the logo of the whole thing--U. S. Steel's model of Planet Earth with three orbiting satellites called the "Unisphere"--were going to set.

My, was he proud of his Unisphere idea. It would stand fourteen stories high, and be the largest model of the Earth ever constructed!

Compared with other exhibits and pavilions, Westinghouse was far, far down on the list, if only they could be politely told. But he didn't have time even to tell them where to get off. The connecting exits and expressways to the site had to be designated and built, commemorative avenues and fancy fountains had to be installed, water, sewer, and light connected. Ford, Chrysler, General Motors, Billy Graham pavilions located...halls, stadiums, flumes, heliports, and the Swiss Sky Ride...all wrapped up in a neat, beautiful package handily accessible to the modern, whiz-bang jet-age world.

No wonder he had to put Westinghouse's little Time Capsule thing off to the last moment.

However, while at Delmonico’s and the lunch that would change human events for all time to come, Moses finally got his bright idea, like he usually did, his own way and when he was good and ready.

Moses made a re-count of his latest figure. "Nope, " he frowned, "still a tad too much. ANNO 6939 is the cut off date for the last Time Capsule. I don't want to be anywhere close to that date, you understand? Now who else can I deduct?"

As he expected, the only woman on the board, Jell-O Heiress June Stonecroft Clutterbuck, would have to refuse.

“Robert, I’m going in that wonderful Time Capsule!” she declared, pointing a steak knife at him. “Don’t you dare think of cutting me out of the future!”

For a moment, Moses was stumped. He had counted on doing just that.

Others, fortunately, weren’t quite so keen on appearing in the future, even if it only involved their good names.

So by hook or crook Moses got his total right. At last, ANNO 5931!--a date distant enough to impress any crowd, Moses figured, yet ahead of the other Time Capsule.

Westinghouse called and thanked him for the date and said he would receive important materials by express courier in a few days, detailing the contents of the Time Capsule.

"Sure, you do that, Mr. Rutherford," said Moses. "I'll be looking forward to it something awful."

The Westinghouse official would have gone on, but the park commissioner had a thousand things on his mind, more important than a time capsule--so he buzzed a secretary on his staff to handle the rest of the call and rudely rang off.

His brusque manner was understandable. He had less than two years to go before millions of people arrived at the gates, and only a quarter of the projected 144 exhibits, special features, and pavilions had yet been completed. It was going to be the biggest fair ever--NINE TIMES BIGGER than its predecessor, the pint-sized Seattle World's Fair. Even if there wouldn't be an impressive Space Needle in his fair, he might still get somebody, some fat cat Rockefeller or Guggenheim, to finance a Space Thimble twice as tall as Seattle, Washington's so-called "space needle" tower-restaurant.

When the Westinghouse packet arrived, so hefty it must have weighed ten pounds, Moses did not even look at it. Miss Renfrew filed the packet with hundreds of miscellaneous packets and unopened junk mail, too busy handing calls and correspondence with foreign countries and embassies to give it a moment of her time.

Destiny, however, intervened to save the packet and its contents from the dustbin of inadvertent, administrative burial.

Forgetting his back condition, a janitor (formally titled "Parks Commission Engineering Specialist") while cleaning up grabbed the overflowing box of packets and hustled it down on a cart with some bags of trash to the building's westside sally port where the garbage was collected.

"Aaaargggh!" he moaned. The biggest packet naturally had to land on his foot with the corns.

Carefully, because of a bad back, he stooped to pick up the mess. He was about to give the packet a fling when his eye fell on the addressee: Westinghouse Research Laboratories. Beneath that was printed in large red letters: TOP PRIORITY: WESTINGHOUSE TIME CAPSULE. HANDLE WITH CARE. CONFIDENTIAL MATERIAL

Something clicked. He tore the packet open. Yes, there it was! A bundle of grade school "letters to the future"! With a blue envelope a memo was attached, signed by some Westinghouse bigwig, requesting that Mr. Robert Moses please respect the confidentiality of the winning letter in the blue envelope, which a Westinghouse committee of "distinguished scientists, artists and scholars" had selected for the Time Capsule from elementary school entries. They requested that he review the other letters and if he thought that one was good enough for the Time Capsule, only then was confidentiality waived and he could open the blue envelope and compare the letter with the one they had chosen. After all, they added, they cared to do the very best for the Time Capsule. If he had no alternate, then he should just send the blue envelope unopened back to them immediately. As for the others, they requested that he please forwardthe losing entries to the applicants and, by all means, thank them for submitting.

Thompkins could hardly believe his luck. He opened the blue envelope and his face fell.

The winner was some girl named Therina Popov.

He looked around to see if anyone was watching him, then removed the blue envelope's letter and threw it in the trash.

He then tore though the others, found his son's and stuck it in the blue envelope.

Even if he hadn't read it, he knew his son had worked his butt off. He even wanted his mother to buy him a dictionary to get the words spelled right, he was so determined to win against the whole third grade and this Popov girl in particular. To become top dog, that meant he had to beat out several hundred entries. Well, this was old New York, wasn’t it? City hall hotshots and crooks had built the town, and that wasn’t going to change for a million years! New York was no place for nice guys. By hook or crook there was always a way for a smart guy to get to the top even if fate threw him a louie.

Now the win was in the bag!

Just to make double sure, he quickly sorted out a dozen or so of the sloppiest and dumbest letters, stuck them in the packet with his son's blue envelope for Moses’s perusal, and threw the rest away.

Singing "Everything's Coming Up Roses," he scooted back to Robert Moses' offices on the fortieth floor of the Empire State Building.

In a minute or two the packet and blue envelope were lying sealed on the bigshot's fancy desk, the first thing he would see when he came in the next morning. He even remembered the photo he carried in his wallet. He looked at it for a moment, thinking how much his son looked like a chip off the old block despite his mother's forehead, chin, nose, cheeks, ears, and the expression in his eyes, then slipped it into the blue envelope.

As usual, there was something waiting for him.

"Strange," he thought. It was unopened. Sec'y Renfrew was letting down on her duties a bit. He might have to throw the old dame a louie just to put her back on her toes.

He took an ornate, solid gold letter opener sent to him from an adoring Sultan of Zanzibar. Set with what looked like a red gemstone, it was kept on the desk just for show. Carefully, he sliced open the packet and saw that it was more Westinghouse Time Capsule crapola to process.

"Oh, now they want me to respond to a thousand of these kids' dumb letters!" he thought. "Here I am with a top dollar world's fair on my hands and the over-educated, Ivy League dopes at Westinghouse think I really have time for this!"

He pulled out the losing submissions and gave them a toss toward a wastebasket that missed by six feet. That matter taken care of, he turned to the blue envelope and read the instructions.

He picked up the letter opener and was starting on the envelope when four lines on his array of telephones rang at once, then five more. He couldn't spend anymore time on it. Where was Renfrew babe anyway? He went out to look, carrying the blue envelope.

She was gone from her desk at the moment, apparently getting the office coffee pot primed, he figured. He scribbled a memo to have her send the winning submission back to Westinghouse pronto.

Then he thought of a perfect comeuppance for an unmarried man-hater with a cold, fishy eye. He typed a little note and tucked it in her desk calendar, a couple days ahead. When she noticed it she would read:

Then, at the grand opening, an exhibit interpreter would explain to groups of at least ten people how a committee of distinguished scientists, artists, and scholars had selected the capsule's contents, which included an electric toothbrush used by a NASA astronaut in Earth orbit, JELL-O lime flavor mix, white-framed horn-rimmed sunglasses and bikini from the Brigitte Bardot film, "Ecstasy," QUELL toilet bowl cleanser, a popular recording of a Beatles smash hit, a feather from Bonasa Umbellus (Pennsylvanian Ruffled Grouse), MacWhyte’s Wire Rope Catalog, and a gilt and leather-bound first edition copy of Robert Moses's: My Billion Dollar Baby: the 1969-1970 New York World's Fair.

1939’s Time Capsule and its Mickey Mouse cup were completely eclipsed!

Crowds of women in light or dark, busy-patterned dresses, the younger women with white-framed, horn-rimmed French Riviera "Bardot" sunglasses, and taupe-clothed men and boys with crew-cuts and white socks, not to mention, the solitary nun in stark black and white, would give the exhibit at least five minutes of their time. They would gaze in wonder round the gleaming torpedo containing their world's “Letter to the Future.” Printed placards informed them that the capsule, at the close of the Fair, would be deposited next to the 1939 World's Fair Time Capsule, Fair Founder Robert Moses officiating along with the “World Fairettes,” professional Rockette hoofers on loan from Radio City.

Though coached for twenty minutes, the guide would be hard-pressed to answer all the questions, especially the one that always came from a bright eight-year-old, "What kinda stuff did they put in the first capsule?" she demanded in a high-trilling voice.

Since the inquirer kept asking the question, loudly, while munching on a dripping Belgian waffle, the supervisor from Westinghouse at the front entrance had to be consulted.

But the super would be stumped too. Once the Fair was rolling, there wasn't a spare minute to find out, so all those who tended the highly popular Time Capsule exhibit would be instructed to inform persistent questioners that they could write to Commissioner Robert Moses, care of City Hall and the Metropolitan Park Board.

That, however, would not be the end of the matter. Unsatisfied, the bright eight-year-old would put other questions which were just as bad.

"How did you come up with that stupid date? And why can't we read the boy's letter that's going in the capsule? I wanna know why his won and mine didn’t. Miss Mabobzadel says I’m the best writer in all her classes. So mine should have won! And why didn’t I get mine back in the mail? Did Wessinghouse and Robert Moses lose it or something? How can they be so careless? Miss Mabobzadel is pretty upset. An’ she promised me she’s going to write a letter to the governor, and if he doesn’t listen, then the president, and if he doesn’t listen, the F.B. I.--”

Grinning like a Cheshire cat, scarcely able to bear it without coming totally unglued, Bruno escaped as soon as possible from the faculty lounge back to his office.

He shut the door, slid the dead-bolts, and then leaned against it, breathing heavily. It was some minutes before he felt composed enough to collapse into his chair.

He had a tape of a Nickolas Bruhn cantata and listened to it, shuddering face down on his desk.

Forty minutes later, he lifted his head and tried to get back where he had left off his researches when the old biddy department secretary had rapped loudly on his door, demanding his presence in the lounge.

How he dreaded that yearly knock! It was the Clap of Doom. He always tried to be somewhere else when it was due, but he could never think of adequate reasons for being out of his office. It wasn’t that easy. People were reasonably intelligent in a university. You couldn’t expect to fool them more than five or six times running. After that they were chary of you, and you were forced to suffer their impositions.

The only worse thing than department birthday celebrations was teaching. Standing up before a class terrified him. He was usually rendered speechless. Most people assumed it was modesty due to an excess of intelligence or an actual speech impediment. No one seemed to guess it was sheer terror of teaching. He wasn’t well liked as a teacher, fortunately, and so his students were few. Since he relied heavily on audio-visuals, he was able to cut his actual teaching to a fractional minimum and, thereby, discourage those students who wanted something else. This system worked rather well for him, and he had been at the University of Chicago for fifteen years, gaining tenure, and had risen to an assistant professorship of Archeoastronomy. The professor he assisted almost never saw him, nor expressed any wish to see him. They brushed shoulders now and then in passing. It was understood that someday the older man would pass away and Bruno would step into his niche.

So Dr. Bruno Hartung bided his time, meanwhile doing as little pedagogy as possible, and conducting research that would cause him to stand well in the eyes of his superiors. They loved researchers, and he had been careful to cultivate that image from the first. Researchers usually published and gained a degree of fame for themselves, the university, and the department. For that reason they were valued above plodding menials who did not covet publishing credits and spent all their energies instructing the ignorant rabble.

“For he’s a jolly good--” The sound of it still rang in his ears hours after the grueling experience was over, making it difficult to concentrate on papers of Mayan research he was examining.

He finished one paper, scarcely knowing what he had read, and then abstractly picked up another and began reading. It concerned a new discovery of a Mayan center on Isla de los Reyes, an islet off the west coast of Panama. The site was so isolated and difficult, the entire party and its supplies had flown in by helicopter.

Thanks his assiduous cultivating of archaeologists in the field, he kept himself abreast of latest developments. Grateful for generous checks written on the department’s emergency expenditure account, his contacts wrote him even before their reports were officially published.

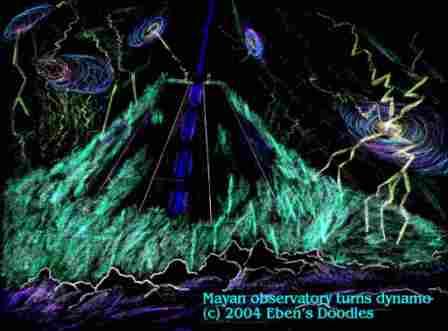

He got to the place where the archaeologist was describing certain glyphs of the Astronomical Observatory when he sat bold upright and his eyes widened.

“--the River of Time’s End appears in No. 345236 glyph, along with the date, which according to their wonderfully accurate solar calendar was ANNO 1912---”

He read it again, then seized a paper from his files for comparison.

Palenque Observatory’s prediction was well-known, and the Mayans had set the terminal date for the end of the Sun and World at ANNO 2012. Carved in stone on the temple observatory at the gateway to Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, the heartland of the former Classic Mayan Civilization, it was there for the world to see. A leaping “Great Fire Jaguar” pouncing on a solar disk, the attendant signs of the calendar date--the glyph was well-documented.

He read the new Isla de los Reyes report again. Then again.

Sweat popped up, not on his forehead, but strange places like the bridge of his nose. He yanked off his sliding glasses and rubbed his eyes.

It was a horrible contradiction. How could the Mayan astronomer-priests--so careful in such things--have diverged so significantly? The cosmic date for the end of the Sun and the world was a sacred thing to them. They couldn’t have two schools of thought on it. They just couldn’t!

He read the portion once again, his myopic, dark-brown eyes pressed to the paper.

An hour later he was in a Yellow Cab with dented fenders and signs of sideswipe and collision along its whole length, on his way to O’Hare and the Yucatan.

“Man, what’s that crap you dragged in here?” he demanded as Bruno pushed some gear into the front seat he couldn’t get in the back seat. “This ain’t no truck!”

“It’s a tripod for my camera and a couple digging tools, and I’ll pay extra if you insist.”

“Grave robber for the movie stars? What’s my cut?”

“Not at all!” Bruno huffed. “I must inform you, sir, I am going down to Central America to study some pre-Columbian artifacts on site.”

“Pre-Colum--what’s that garbage? And where is this 'Central America' anyway? You mean the Middle West? Why, all you egghead types always think you're one fart better than the rest of us and can talk some other language!”

“Think what you want. I’m in a hurry, if you don’t mind.”

The cabby gave a snort and rammed his foot on the gas. The cab shot forward in the crowded street, giving Bruno the scare of his life as they careened past the Elevated and nearly sideswiped a bus.

“Hey!” Bruno cried. “Not that fast.”

The cabby’s head swung round and Bruno got a savage look.

“Listen, Phuddy Duddy, you don’t tell ME how to drive. Got that? I’ll get you to the airport, Professor Know-it-all, and HOW I do it is MY business! Got that? If you don’t think you got that, then get your ass out, or I’ll throw you on your head and watch you bounce!”

So the archeoastronomer kept his mouth clenched shut, though it was all he could do not to scream and fling the door open and jump.

At the airport unloading zone the cab skidded to a halt, throwing the passenger and his gear to the greasy, cigarette-butt covered floor. A shaken Bruno got out of the cab with the smoking, balled wheels, paid up, and made it to the terminal with his gear. He took out as much insurance as he could on himself in his wife’s name, called her to let her know he’d be out of town a few days on department business, and then headed to the plane.

“Please ride along with us, Senor Dr. Dunmire!” Bruno was told. “We are most greatly happy to have you present, and many comments I am glad you contribute, please.”

“Fat chance of that happening,” an aging beauty with blue and red-tinted hair broke in with a shrill, metallic voice as she sipped Bloody Senoritas with another aging lady who looked far more resigned to her mature age. “Hit ‘em hard where it counts, I told my friend in Sheboygan. She always thinks men will do the right thing if you let them alone! Fat chance of that! So I had my attorney slap a nice little lien on his accounts, or I’d be walking the streets penniless. Now--and it’s the jerk’s own fault--now he’s staying in some run-down motel room and panhandling in Vegas, I’m told.”

The dumpy-looking woman at the other table in the airport restaurant pushed back a Neiman-Marcus diamond and emerald bracelet on her wrist to check her watch, a man's watch with a big dial she could more easily read with her macular degeneration. She wasn't on the market herself (hadn't been for quite some years, in fact), but she knew how to please an old girl-friend she constantly travelled with from resort to resort. She glanced toward Bruno and the guide, rose and came over drawing her the blue-red tinted friend along, who managed to reach the destination first.

“Are we going now, Manuel?” the grandmotherly-type said sweetly, nodding at him and glancing at Bruno and the blue-red tinted lady significantly.

Manuel, rising, graciously introduced them.

The blue-red tinted lady was impressed, just as the guide had been, with Dr. Dunmire’s background.

“Well, wouldn’t you know it? Small world! I’m a Carbondale girl and had a pretty good time at USI, let me tell you, but I have tons and tons of University of Chicago friends. Which department, professor?”

Color draining from his already pale face, his glasses sliding down his perspiring nose, Bruno didn’t like this turn in events at all. Fortunately, the guide hurried off to see about the bus.

“Dentistry,” he said in the dullest tone he could possibly manage.

Her face brightened, then turned doubtful as she looked him over.

“Well, I don’t recall your name or seeing you there,” she declared. “I just had all my new bridge work done there, wouldn’t you know? They all adored me there. I got to meet everybody in the faculty after they found out I could mix the best martini they’d ever seen. I never forget a name or a face, no matter how many drinks I take, but your’s, I’m afraid, don’t ring a bell! Now why is that?””

Bruno squirmed on a kind of hot seat. It was rather stifling and noisy in the restaurant, what with the clatter of utensils in the kitchen and the shouts of orders going back and forth between waiters and cooks, but Bruno’s problem was wearing Neiman-Marcus bracelets and puffed blue-red hair.

“You see, I was ill and couldn’t made it to graduation,” he said, hoping the lame excuse would do.

The woman’s eyes squinted a little as she examined him more closely. She seemed to be about to drill him with more questions.

Just then the guide hurried back, handing each a complementary fruit basket from a cart and calling them to board.

Avoiding anyone on a crowded bus at numerous, time-consuming stops in native markets is difficult, but Bruno managed to escape the blue-red hairdo’s questions and also requests he look into a gum problem she was having with her new bridge work. Not just once was he obliged to exercise nimble legwork to elude her, leaving one lady with an extra drink he had really needed.

Taking a native bus he escaped the blue-red haired virago and caught a flight from Villahermosa. With several connections in adjacent banana republics, it eventually landed him in Panama City, terminus of the Canal Zone and port city on the Golfo de Panama. Really the last civilized outpost, Panama City provided, logistically, the only gateway to Panama’s largely unexplored, tropical west coast.

On his map the Isla de los Reyes lay about a hundred miles across the gulf to the southwest. It might have been a thousand instead, for he asked everywhere and couldn’t get any connections. From helicopters (the pilot refused to take a check unless it were confirmed by the University of Chicago by telephone) to charter boats, he met with pleasant, amused stone-walling or rude, outright refusal.

“Nobody wishing to go there, Senor!” he was told repeatedly, though he related how a British expedition had recently visited the island. “You want go there? But she plenty bad place--plenty big snakes, big spiders, and the demon-cat Pocatecopetzal that claw and burn man bad down here in the sainted cajones, Senor--”

The fellow, illustrating his horror story with obscene gestures, was plain enough. But Bruno was not buying. He had proof the place had been visited and the expeditioners, evidently, had got off alive and well.

But how was he going to get there? Swim? The gulf was infested with sharks, sea snakes, poisonous jellies, and giant sting rays. The beach, as anyone could see, was loaded with people, but no one was swimming.

The archipelago, of which the Isla de los Reyes, formed a part, should have had a ferry service for inter-island marketing. But again, there was no such thing. Each island’s inhabitants, if there were any, fended for themselves in conditions approximating the Stone Age.

Like the others, the Isla de los Reyes possessed one village, and on maps at least carried the name of San Miguel, but apparently they were too poor and never went anywhere in the few boats they could muster to do some fishing. Even the postal department did not deliver, not even semi-annually, as he found out after a long, nerve-racking search for the building by local pedi-cab.

At his wits end, Bruno collapsed with his gear in the port. He had asked every fishing boat captain to take him, and met stony silence or mad Latin hilarity. They could not be budged, not with University of Chicago, Science Department checks--and he hadn’t sufficient cash.

He paced up and down after stripping off a turtle-neck sweater and tweed coat.

Little boys followed him, gaily remarking on his strange gringo appearance until he had drawn a considerable crowd before he noticed and stopped pacing.

He turned just in time and spotted a man lifting his gear to his shoulders.

“Hey, that’s mine!” Bruno cried.

“But I carry, Senor, to your boat, yes?.”

“Are you crazy?’ Bruno cried, beside himself. “I have no boat.”

“Yes, Senor, you have no boat,” replied the equable porter, taking the gear and plodding off down a dock toward a crammed jumble of brightly-colored fishing boats.

Shouting for the authorities, the outraged professor followed.

Stopping by a boat, the porter dumped Bruno’s gear and thrust out his hand.

"Please to enter boat, Senor!"

The boat’s skipper, a sometime fisherman and mostly smuggler of contraband arms to various anti-government groups, nudged Bruno.

“We go at once! Hurry! Police will demand all his money from gringo, so vamos! We go quick!”

Bruno’s gear was thrown in before he could stop it.

A moment later, Bruno was practically thrown after his camera, tripod, sleeping bag, film canisters, checks and research papers, and the boat cast off into a sudden rain squall that threaten to pitch them amongst the sharks, sea snakes, and poison jelly-fish.

But the boat wallowed out of the storm and they made it to safety, the skipper pulling a crucifix from his dirty shirt and praying them in with mingled oaths, shrieks of fright, and Ave Marias.

At San Miguel on the island Bruno was lucky to save his shirt and pants from the rapacious smuggler. The man pulled a semi-automatic on him and wouldn’t let him go before he got his watch, pocket money, wallet, shoes, even his precious camera and tripod.

“Thief! Robber!” Bruno screamed at the man as rain poured down, drenching him anew with gallon after gallon of tepid water. “I’ll have you arrested for this as soon as we get back to Panama City!”

Utterly forgetful of the urgent prayers he had lately offered up to Providence, the villain laughed with crooked, black teeth and spat, heartily amused by this specimen of gringo.

“Gringo I like to throw to shark, but I am a good man and let gringo go here in this nice, little village. Women very nice to gringo here. They are not fantastic beautiful maybe. But gringo pay nothing. They feed gringo, he eat. Gringo eat and sleep a lot and do as gringo please with women. They don’t mind. Gringo stay here a week, maybe two weeks, maybe two years. How do I know? If gringo get away he will be very happy, not angry, si? But gringo may not get away, si?”

The boat pulled away, leaving Bruno at the mercy of the locals, who straggled out from the miserable ring of huts that lined the “port.”

Nobody at San Miguel could possibly help Bruno recover his possessions. Too poor for even a barefoot, machete-armed policeman, the village supported no government official of any kind, and Bruno was forced to face the grim facts alone. Without a dime, he sat down at a ramshackle cafe, numb with his losses. It was the only place with a tin roof that kept out the downpours, more or less.

The Indians--for there didn’t seem to be a single Spanish-blooded person in San Miguel--stood around and stared at him. The small fry played in the mud and puddles, the infants naked and up to their waists in the muck.

He accepted a gourd of tepid rainwater, if only because he was racked with thirst by this time.

The heat and insects were appalling, but the rains were worse. They thundered down on the roof until Bruno’s stockinged feet were washed in muddy water and pig offal--for a pig shared the cafe with the playing children and the standing, lounging adults.

Discovering a leach wriggling up his ankle, Bruno decided he had to go.

Escaping the cafe, Bruno started to climb the steep mountain trail behind the village. It soon dwindled and he was forced to begin climbing through a choking tangle of vines and tree trunks.

According to the map in the papers he had lost to the smuggler, the island’s high point was 1, 200 feet, but it might as well been 12,000, the summit was so difficult to obtain. Additional information given in the report told him the Spanish explorer Balboa had first sighted the island from the mainland after his discovery of the Pacific Ocean. Indian guides, when asked, said it was the “Island of the Kings,” so Balboa had named it after the Wise Kings of the East, the Magi who had visited the child Christ’s home in Bethlehem with kingly gifts.

He was soon hopelessly lost, wandering with no idea which way he should go. If he climbed a tree, he might see the way, but the trees were so choked in vegetation, wet and slime-covered, he couldn’t possibly get a foothold.

The reports about the island were not exaggerated. Once he grabbed hold of a thick limb to squeeze through a thicket and felt the “limb” come squirming alive under his fingers.

No snakes could be that big, but this one was!

Shrieking like he was set afire, Bruno fought to get away, tearing his clothes to shreds in the thorny shrubbery and losing his glasses. From then on he couldn’t see anything distinctly and was deathly afraid to touch anything, for fear it would turn out to be another giant snake.

Bleeding, burning with fever, his clothes hanging in tatters, he tried to get back to the village--but it eluded him, hour after hour. He lost all sense of time. Rain and more rain, a river that let up for only a few minutes at a time.

Hours after leaving the village, Bruno crawled and stumbled into a clearing.

He collapsed on the ground, unable to move for some time. When he felt better, he looked up and around, then his mouth fell open. He didn’t see the usual dark blur of dark tree trunks, all intertwined like thousands of snakes reaching for him. It had to be the summit!

Barely able to stand after his ordeal, he got to his feet. The rain cloud and jungle lay beneath him, and he stood there for a while simply drinking in the sunshine and fresh breezes.

His feet, legs, face, and arms were cut and bruised. His buttocks showed through his ripped pants. But he scarcely noticed. He had found the site!

There was little to see of the observatory, since the crowning temple was reduced to the foundations, but he found signs of the expeditioners’ initial excavation. Fortunately, he had not arrived too late. A few more weeks and vegetation would have re-covered everything.

He flung himself down to look for the glyphs he had seen in the photographs and drawings--evidence he had traveled thousands of miles to see for himself.

Again, good fortune shone on him. His face pressed as close as possible so he could see, he found the glyph with the Springing Great Fire Jaguar and the vital dating zoomorphology. Along with them were glyphs that were new to him in subject matter. They told of how priests gathered the “Fire of the Stars” from a central reservoir and taking tiny bits of it on spools like women collect yarn on spindles they fashioned small “Stones of Powers” which enabled them to do many great feats of magic. These things they said they learned from codices bequeathed to them by the “Ancients of the White Land,” the “Lost Land of the Plumed Serpent.”

By this time the Sun was setting, coloring the entire gulf with pyrotechnics of blazing red and gold. Scarcely noticing while he was lost in his reflections, Bruno only came to himself when he felt the temperature dropping.

“Even if I can’t see much of anything, returning to the village should be a snap,” he reasoned. It would be downhill, after all.

But first he had to make a rubbing--proof the expedition before him had not fabricated the incredible discovery. Fortunately, he had taken the precaution of putting the rubbing paper in a plastic envelope in his pocket. It was still there!

While he was rubbing the most important glyph, it began to glow reddish behind the paper.

Springing up to his feet, Bruno wondered what could have caused it.

Then he grew aware that something was happening. His feet were shaking.

An earthquake?

But the shaking was not violent. It continued, a humming sort of sound accompanying the vibration, and Bruno was dumbfounded.

He walked out and around the crest of the mountain. It continued to vibrate and hum. The vibration, however, paused periodically, then resumed, each time at a higher pitch and frequency.

Gradually, it dawned on him.

“Could the stones of the observatory somehow have become charged with positive and negative polarities? By a lightning bolt perhaps?” Electro-magnetic forces were, beyond question, highly active in the mountain.