O F

T H E

P H O E N I X

O F

B R I T A N N I C A ,

V O L U M E

I V ,

A N N O

S T E L L A E

Their country destroyed, nearly exterminated as a race, the once world-shaking Britons (whose commanders once held the reins of power in Imperial politics and even claimed the throne) seemed to have disappeared off the earth, even their name extinguished by the barbarian Germanic tribes who came in flotillas of overcrowded boats, weighed dangerously to the waterline with their wives, children, and even their livestock. A vast host, these land-hungry barbarians crossed over the water and destroyed Britannica. Almost, but not quite!

Despite appearances, some Britons survived to fight and hold on in various, out of the way spots, and thanks to them true Britons still exist 1700 years later after the illegal occupiers turned into the Anglo-Saxons, but what happened to the the people they killed and pushed out of the way? They are the Welsh, the modern descendants of the survivors are called "Welsh," who are the original native British people once inhabiting Britannica, and still are living in the region on the west side of the Island called Wales. But what is Wales? Most everyone knows Wales is not an independent nation and cannot claim a seat in any world body of nations. Yet little Wales is a rump principality, all that is left on the Island of old Britannica, in truth--conquered and held by its more powerful neighbor, England and its monarchies for over a thousand years.

Reduced to a minor province of the Norman- English kingdom, it had been isolated, poor and backward but proudly free for centuries before that time, shedding the blood of every generation of its own and the Anglo-Saxon usurpers as well, to keep that precious freedom. But eventually, the much stronger, more populous and rich neighbor, the Anglo-Saxon and later the English kingdom, won out. Centuries passed while Wales was not its own kingdom, it had no ruling dynasty of its own. Rather, the sole ruler was appointed by the English overlords! Then in the 19-21st centuries, the Guelfs, a German ruling family imported from Hanover in northern Germany, came to represent the old Anglo-Saxon and Norman kingdom which could no longer muster a viable reigning dynastic line of its own.

Changing their name to Windsor, the Guelfs gradually turned more English than their subjects, though at first the Guelfs heartily despised the English and were most reluctant to come and rule the country, even though they had been invited.

As for Wales, it suffered far worse indignities than England knew under the rather stuffy and ungrateful Guelfs-Windsors. What was to be done with England's dependent, poor, and troublesome principalities, such as Scotland and Wales? For Wales, someone in the royal officialdom thought to create a regular princedom of it, with a real prince of the Guelf-Windsor line, of course, set up over it. So, it was done! One foolish, frivolous nincompoop after another of the German Guelf-Windsor royal family was trotted out in pathetic succession, each given the title "Prince of Wales" in a ridiculous ceremony at the Castle of Constantine, lately called Caernafon Castle, in northwestern Wales.

Could the original, native British be more degraded and ruined, than to be ruled over, even if ceremonially, by one silly fop after another, and absentee foreign princes at that? Every Welshman worth his salt could see these "Princes of Wales" knew nothing and cared nothing for Welsh ways, traditions, and an undying thirst for freedom.

But who will shed tears for the once proud and noble Britons of Britannica, later relegated to the poor and rocky edges of Wales, the land of the White Dragon, white, perhaps, because it was bled white by crushing English taxes and royal levies?

All this decline and disgrace came about in an innocuous, seeming expedient and harmless way, that got out of hand. In this way Britannica slipped from the center stage of imperial Rome, where it had figured very prominently, even to seeing emperors crowned in York and traversing the country to build monumental walls to keep the barbarians of the north out as well as see to the strengthening of other defenses. Much Roman blood and treasure had been expended on Britannica--all seemingly in vain when the German illegals began arriving with no intention of leaving.

As often happens, weakening kingdoms that have lost their fighting or martial spirit to some degree, seek the aid of anyone who is strong and warlike and willing to do military work abroad for payment--but this paid army is bound to go wrong sooner or later, as the mercenaries see first-hand how really weak their employer is and decide to take the whole kingdom, rather than just occasional sums of gold and silver.

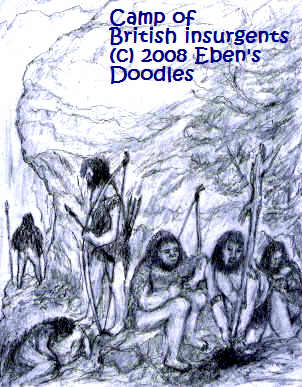

Inviting some mercenary German tribes to come in and help them push back the land-hungry northern tribes that were pressing down from the north, Vortigern (the British leader) got much more than he bargained for with British silver. Thousands of barbarian German tribesmen poured in from across the Channel, and then began grabbing everything in sight. Forced to defend their homes and country from these former allies, the Romanized and Christian British fought the pagan barbarians for three hundred years, half that time alone, utterly without Rome's military help after the legions were withdrawn. The vastly outnumbered, less warlike British were annihilated for the most part, but the survivors fled to the mountains of Wales and were able to mount a successful resistance to the Angles and Saxons and Jutes (who didn't do so well in high country, preferring to duke it out on the level plains). Though all their high civilization was lost and destroyed by the burning, looting invaders, they at least had preserved their freedom and identity as Britons. Cold, half-starved, scantily clothed in bark and leather, moving from place to place without shelter to camp in the most inaccessible crags, the British insurgents continue their struggle for existence--and remained unconquered, though most of their country would never be regained from the newcomers.

Weary of the cold, damp, and the dirt of various hideaways--where they waited for enemy patrols to pick them off with well-aimed arrows or avalanches of rocks--he decided to invade the occupied territories and see if he could find his old home--for he had to see it once again and pay homage at the graves of his parents where the enemy had murdered them, before he died childless, without wife and sons, in the miserable Wales where he and his remnants of a British people had fled.

"Don't talk, son! There is no time. Do as I say now, without delay. Take my seal and estate title, and flee the house immediately, by the gate in the back garden--which the Germanii will not know about. And remember, for I will tell it to you now, our most ancient name is--"

He gave the name of the family to Honorius, in the original tongue of the ancient Britons, not their adopted Latin.

But Honorius thought of himself as an Urbani and was not particularly interested in the family's archaic-sounding Gaelic name just now, or in his father's paterfamilias insignia and the estate's title deed.

The Germanii, attacking their home? Honorius leaped to his feet from his bed, half-clothed but reaching for his sword and shield (awarded him in anticipation of his majority celebration, which had been scheduled in a week's time from this day.

His father caught his arm. "There's no time for that. Besides, you are not grown a man, and they will kill you too. What hope for us then. My name and our line will perish with you. So just take these things of mine--they are your legal claim to our estate, our name, and our ancient honor! As for your mother, she has already taken poison, rather than be ravaged by these brutes! Your sisters too, and the women servants, have taken poison too--to escape being ravaged and made concubines of the barbarians." Honorius was appalled. He struggled to get his arms and go at once to fight the Germanii who were shouting and screeching in their barbarous tongue while rampaging through the first floor of the villa, but his father seized him and would not let him do it.

"Now do as I say, or all is lost! Your mother is counting on you, and I am counting on you--do this for us, flee at once! Our men servants are loyal, and they will fight hard at the doors and windows to keep the barbarians from getting to us here for a little while yet, if you will only hurry and do as your father commands you!"

His father pushed him toward the window, yanked down the curtain, and gave him the end, along with the rolled scroll of the title and his seal ring.

"But Pater..." Honorius pleaded, hoping this was all a big mistake.

"Go! Your mother and I accept our deaths--we will look upon our murderers with peace and forgiveness, foul barbarians and heathens though they are, and face them as true Romans and Britons who know a living hope in our Risen Christ! They can take everything else--but not our true treasures in Christ!

Now go, son! Run, and preserve our most ancient name and British honor in your living, and later marry and father sons of your own! You can always stand and fight later on, when you are a full man! There is plenty gold and jewels for you in the well --which I laid there for this very day, knowing it would be coming. Return for the family treasure, which is your inheritance and patrimony, and also bury our bones properly, only when you can do it safely. Now, farewell!"

Honorius saw it was no use resisting any further. His father would not hear of his staying.

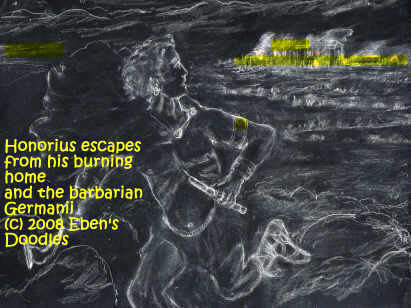

Obediently, though everything in him wanted to remain and defend his mother and father ad fight the barbarians to the death, Honorius slid down the curtain from the second story chamber.

He listened, and heard no voices or footfalls, and then opened the gate and started running as fast as he could. Unsurpassed for his speed among boys his age, he soon put the villa behind him in the distance, but he glanced back, and saw something that made his heart almost die in his breast. The entire villa and outbuildings--all were blazing! He could see something else. His native city, a few miles distant, was overrun at the same time and was burning.

Tearfully, he continued climbing up into the hills and gained the safety of the thick woods and craggy peaks. He knew them well from many hunting trips with his father but which these aliens and barbarians would not know, it not being their country since birth. Despite the darkness and the thick trees, he could make his way through it, following trails he had traversed since earliest boyhood.

Days passed as he clung to a spot amongst trees and rocks he considered high and safe enough. With much solitary time on his hands, he could not help reliving the terrible day with all its surprise and horror and loss. His parents brutally slain, no doubt! All the servants hacked to pieces by barbarian swords and knives! But they would not plead for their lives, as he knew them very well. They were all Christians and despised death. It had no hold on them. Their souls would soar to Christ! The barbarians did not know the triumphs of the Risen Christ who had conquered the Great Serpent the Devil and the world and all its evil, and they would die in their own time, unrepentent in their sins and brutal ignorance, but they had no such hope and certainty as the Britons knew. The Germanii, despite their boasting and their weapons and their destruction of civilized people, plunged staight to Hades, to the land of shadows, even to hell, where the evil dwell and are punished forever when they die.

"Good riddance!" Honorius thought.

Let eternal torment in hell be the fate of all the barbarians, these cruel, stinking invaders and destroyers of his beloved and beautiful country! They deserved nothing better, he decided, for already he forgot his father's Christian faith and hated them, wishing they would all sink into hell forever. But vengefulness could not fill his aching loss. His parents, his family, his former life, and he could not help but mourn the loss of his native city too.

So he had obeyed his father, though it was very hard for a young man with his fiery emotions. What followed He had never known such hardship as he discovered in the hills, where he hid day after day in the cold, damp, hungry and without shelter, waiting for the barbarians to depart. Yet they seemed in no hurry, and camped amidst the desolation. They feasted on the Urbani cattle and sheep, killing and eating everything, down to the last horse, donkey, and chicken. When even the dogs were consumed, Honorius, who crept back close enough to the slopes overlooking the estate to see that there were still barbarians on the site, observed some of them occupied with loading ox carts and realized they were making rather desultory preparations for departure. Even then, it was no telling when they would finally go and he could safely return to bury his family and retrieve the family treasure.

It took the barbarians several more days to complete their work--loading up all the things they fancied and thought valuable, though they destroyed most everything that the fires had not already ruined. Though Honorius did not see it, a last bit of barbarian fun was accomplished--blocking up the deep, pure running wells with big rocks and earth, as if they thought the residents might return from the halls of death and restore their homes and farms!

That done, the barbarians departed. They were all drunken from sacking the wine shops and wine cellars they had broken into and were still celebrating their trumphal march, wagons full of booty, girls and women they had spared to be made concubines, and various things they had thought not worth throwing in the bonfires. All books and crosses and paintings and tapestries and other fine things, of course, were thrown in the fire to heat their cooking pots or roast whole cattle, sheep and pigs on spits.

But there was trouble on the Continent, which they had little knowledge of in water-moated Britannica. His pater didn't like what he saw in Gaul, as the barbarians had made many raids throughout the whole province, burning and looting and driving people out of towns and cities and enslaving all they didn't first kill. Because the barbarians from the east might come back at any time to attack more of Gaul, it was best not to linger and travel with speed. Staying in inns, following travel maps that were provided them, they knew exactly where they were at any time, and could determine how far they had yet to go. On horseback, they made their way quickly.

Even northern Italia, after they climbed down through the passes in the mountain, was ravaged and deserted! It was a big disappointment to them. A talk with a veteran returning to their own home isles after long service abroad further discouraged them. The Emperor had left Roma and gone with his court to another city, on the eastern coast of Italia, one that was better defended than Roma could ever be, the veteran informed them.

Yet they must press on, regardless, Honorius's father decided.

But not much further on, suddenly everything changed. They met a strong Roman garrison, and beyond the country was as well run and ordered as Britannica. The people were prosperous, and not at all afraid. To them what had happened to Gaul and northern Italia was unthinkable, and life continued as it had always done. Could Roma fall? Never! they laughed as Honorius's father asked them about their defenses, would they hold or not. It was just a week or so when they set out from an inn on the outskirts of Roma and then saw the skyline of the world's greatest city, set like an Egyptian colossus across five hills, with its mighty walls stretching across the whole horizon! Even without the Emperor present with his royal court, the city still appeared the ruling city of the earth. He would never forget it, though he was but nine years old at the time.

Oh, the statue-crowned gates, packed with all manner of people of every color and manner of costume from all across the empire, hailing from Europe and Asia and Africa, and every sort of conveyance loaded with goods and people, and soldiers of the legions decked out in a multitude of plumes and shining helmets and magnificent scarlet uniforms!

The noise of the thronged streets was deafening, while he and his father made their way through to the most ancient Forum below the Palatine Hill, pausing to look in at the glorious churches and basilicas, passing the Baths of Carracula, the Pantheon converted to a church, and the Coliseum, and the great forts inside the walls, and the innumerable palaces and mansions of the patricians and senators and the wealthy classes. There seemed to be millions of people packed jowl to jowl inside the walls--to Honorius's awestruck eyes. Little Glevum shrank to a flyspeck next to Roma. Roma could contain a thousand Glevums, maybe ten thousand, and still have room to spare! The amphitheater where the chariot races were held seated 300,000 people, and the Coliseum, despite its towering size, "only" 50,000, his father told him. After finishing his business ordering a shipment of very costly pepper to be sent from a warehouse to Londinium, and thence to Glevum's merchants, they were free to explore some more, then on the way back, crossing over the mountains to take a short trip by boat on the Adriatic to Classis, the port of the new imperial city of the Western Empire. But this proved a let-down after Roma. Ravenna, moated by swamps, with its only access via the port, was a small place compared with 1,000 year old Roma! Its churches were very large, but no larger than Roma's, and rather empty of people--so they didn't spend much time in Ravenna--for aged but still glorious Roma had spoiled them!

The golden towered vision, the Eternal City, faded, however, and the reality came crashing back upon him. For all its seeming might, glory, and wealth, when he was but ten years old, news came to Glevum that Roma was sacked in 410 by Alaric and his hordes of barbarian Visigoths! How they all had mourned, and taken down every flag and hung up black cloth in its place.

But barbarians had been attacking the empire for a long, long time, all seeking lands, plunder, and even a chance to loot Rome of its fabled riches. Britannica was already under a protracted, bitter siege, and had been for over a hundred years, and when the legions were withdrawn, she had to fight on alone against the barbarians--a war that had no end, until, that is, they lost to the barbarians in the unequal struggle!

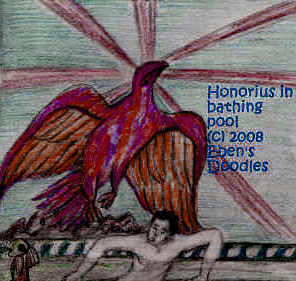

Thanks to that defeat, he was in outlying, backward Wales, not even his home country. How dirty he was feeling! He wanted nothing more than to sink his whole body in to clean hot water of his family villa's bathing pool--with its furnace beneath keeping the tepidarium at the right temperature and the piped water always refreshing it through the mouth of a fish. How sweet that had been! His head back against the tiled wall, which featured a rising, triumphant Phoenix bird rising from the ashes of death and destruction, he felt as if he were floating on a feathery cloud!

How could he remember all the words now? It seemed a marvel, a miracle to him! His father's God had visited him in his lost estate, in the very depths of his losses!

But he fell to wondering what use it was. Could God restore what he had allowed the barbarians to take away? Could his parents be brought back to life, and the estate rise again from the ashes? Surely, not! They were lost forever! So what hope was there for him? He was alone--cast away an orphan in the wilderness, with no one to help him! What use then was knowing the Lord, "the king of kings in all eternity"? The Lord failed to protect his family, house and estate, and had abandoned him to his enemies!

Bitterly, Honorius fought the song, and the message that had almost ignited hope in his heart, died a way, and he no longer thought about it as he meditated on the ruin of his once shining prospects.

At last, after a week or more had passed, Honorius could bear no more waiting alone and starving in his high, safe, but unbearably wretched haven.

Creeping down fearfully from the hills, starved thin and weakened, Honorius intended to find and bury his beloved mother, father, and sisters and even the household servants who had so faithfully served the family and even died defending them.

He found some shafted arrows in the pasture, and gathered them, and then came to a forgotten spear, and took that too. But when he came to the house ruins and went round to the front, he saw a sight that nearly stopped his heart.

The barbarians had hung up all the bodies of the slain Urbanii and the servants on tall stakes--the trunks of a row of cypresses they had stripped of branches, and they were covered with carrion birds who had not quite finished their work.

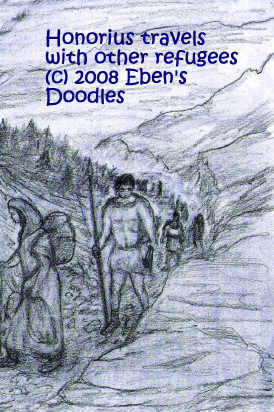

When he collapsed, he lay like a dead man. But hearing voices, he stirred, and realized it could not be the Germanni but his fellow countrymen, survivors like himself from the various estates and cities attacked and burned, also fleeing to the outermost parts of the Island beyond Britannica.

Men, women, children, some of them wounded, some of the women raped, even the children abused, had somehow managed to elude the barbarians, who had grown so drunken and senseless that their captives had taken the opportunity to run away--some of them even with iron manacles still on their arms and ankles. Joining with them in their journey, hearing their various stories, Honorius felt somewhat relieved and comforted, for all shared the same sorrows and losses--and so they could share the misery.

This news was too much, and many gave up at this point. The cold and wet, and the lack of food, took all but the strongest. The weaker ones gave up first, not wanting to live any longer, and just lay down by the wayside and died.

But something in Honorius did not want to do that. Even if Isco Silurum was gone, he might find someplace else to inhabit. He kept plodding on, even though the troop shrank down to fewer and fewer numbers.

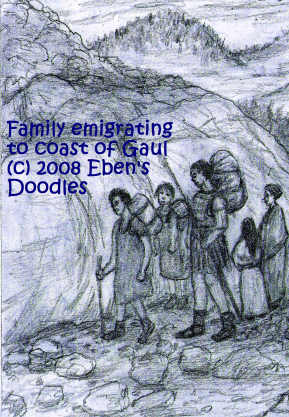

One family--a father with two sons, a young daughter, and wife, had escaped the barbarians when they attacked their city and got away, taking only a few things but enough to help them on their journey.

"Why not you too?" he asked Honorius. "If you have no other family--as it seems--why not seek a new life where we are going? We have room with us for a good youth like you--if you care to accompany us." Honorius shook his head. "It is a kind and tempting offer, but my father laid by a treasure on our estate, my family's patrimony, which is my inheritance. I must return for it, and bury my family properly, when I have opportunity, that is. That is my first duty. After that, I may find some place of my own and buy and settle it--where the barbarians do not know of it, that is."

The emigrant nodded, then gathering his family moved away, gripping his spear and keeping a wary an eye out for any bandits or barbarians.

One day, however, she too faltered, one leg dragging, and an arm hanging useless at her side. She struggled off the trail and sat down on a rock. Turning back, surprised at her movements, Honorius went to her.

"What is the matter?" he asked her. "Are you ill, or did you hurt your foot?"

She looked up at him, and smiled. "No, it is something else. But the Lord is with me, and He said He would never forsake me."

She looked away at the line of refugees. "But you must go with them. I will remain here and rest a while."

Honorius shook his head. "I don't believe you intend to rejoin us! You must be ill! But you must not give up! If you stay behind, you will die in this wilderness. There is no protection for you apart from us."

She smiled at him again. "You are wrong. The Lord is with me! He cannot fail me! Whatever happens, he will take me to himself--so I do not fear man or anything else. So go, young man! But what is your name?"

"Honorius. My father is the chief magistrate in Glevum and deacon of the church."

"I will pray for you, Lord Honorius!"

"Pray for me?" Honorius snorted. "You are the one that needs prayer! You will die here alone. Please get going--I don't want that to happen to you, old one!"

"But I cannot walk any longer. It is my time. I know it."

Honorius stared at her. He shook his head. "I--I will help you walk, just lean on my arm and--"

She pushed away his offered hand. "Thank you, but it is not necessary. We would both not be able to keep up. No, you are young, I am old--it is time for me to remain here, and you are to go! There is life before you and--"

Her eyes brightened. "And the Lord has shown me some things about you just now. I was shown you will go through some hard years ahead, but there is a golden light, and a bird rising out of ashes, spreading its wings over you. Together, you will rise toward the light, and the light will overspread the whole dark country, our beloved lost homeland. Could it be you will bring the word of the Lord to the heathen who have driven us from our country and our homes? Are you the evangel to the heathen Germanii?"

Shaking his head, Honorius backed away, stumbling over a rock and nearly falling on his back. "You are mistaken, foolish old one! I would never be the one to bring hope of the Gospel to the heathen and the barbarians, not after what they have done to us. They fouly murdered my parents and my family, and destroyed our estate! Now I am a pauper and an orphan, thanks to them! I will never forgive them! Never!"

Though he heard the old woman's protests, he rushed away. What was she saying? He did not want to hear any more! Out of breath, he caught up with the other refugees. When some asked him about the old woman, Honorius was not about to tell them what she had said. "She is tired and must rest," he told them. "I offered her my arm to lean on, but she refused. So what more could I do?"

As they travelled, they foraged for whatever food there was. Those who could hunt and had bows or clubs, could bring down small game and even some deer--but there were very few animals as they penetrated deeper into the country--for many refugees had gone before them and eaten and hunted everything to extinction. Hunger stalked the refugees, and took its toll. Starving, the line began to thin out as more and more refugees weakened and gave up the struggle.

The men and boys learned how to forage in the mountains for anything edible-- and they learned hard, for most of them had known civilized city or estate life, and Honorius himself was of the equestrian class, in equivalence to Rome's, which was just below the patrician or senatorial class.

The elite castes and professional classes and high sounding ranks of Imperial Rome no longer mattered or made any sense at all in the savage mountains of the Silures. Proud and illustrious Britannica was no more. Honorius had to resign himself to a low brutish life, roving from place to place like a wild animal, setting up makeshift camps and adjusting to a new life among men and boys who lived the same brutish life, until they all grew rough and used to not having regular baths made pleasant with scented oils, and hot and cold water, soft clean linens, and soft beds afterwards with blankets and fashionable clothing.

For quite some time, he dreamed about meals prepared for them set on gold or silver-edged glass plates along with flowers in vases and music from trained musicians and witty conversation and all the other amenties Rome had brought to the Island as civilization--only to wake up and groan, as he looked around at his fellows who curled up together like dogs in a kennel, realizing there would be no delicious and well-prepared food, no glass plates, no music, and no civilized company and intelligent, educated conversation awaiting him.

Gradually, he sank into the barbaric life that he had despised as the condition of the Germanii. They seemed to like it well enough, but he never could--since he had not been born to it--but what was he to do? Complain every day, that he had lost such and such? The British had all had lost their former good life--yet there has to come an end to crying over it. As for his parents, he grieved for them for a long time--but eventually too the terrible loss was softened or blurred by time, and he began to take his worsened life as something he might accustom himself to, as much as he could, that is.

To fight the new circumstances was to invite death, just as he had seen some formerly strong men give up, lose their will to live, and lie down to die. It was courting death, he knew, when they could not accept the barbarous change in their fortunes. No, he would not do as they did--he was too young yet, and he wanted to live, even if he could not change his life much to the better.

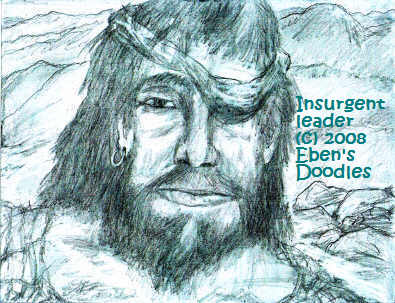

Gradually, the men forgot their former fine life as Britons and hardened into warriors, and Honorius, his education giving him an advantage, grew into a leader of a small band. He and the others under his command took to the life of marauding bandits, roosting in the high hills looking down upon some settlements of the invaders, who were now beginning to farm the lands they had stolen and lose a little of their soldierly watchfulness.

So Honorius and his men made raids upon the invaders, taking some revenge on them, as much as they safely could, without rousing a whole army to come against them.

For some years this continued, until Honorius grew bold enough to try to return to his family estate, even though it lay rather deep in enemy territory and he might be caught and slain in the attempt.

But he learned his lessons well in the mountains--how to travel by night, and keep to the covering forests, and walk down streambeds, and keep out of sight. He had learned the arts of stealth, and was an professional phantom, a shadow warrior.

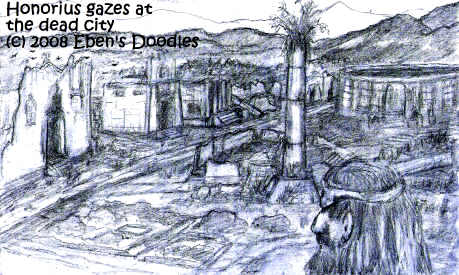

Finally, he stood once again in Glevum! He had last seen the city intact, with all its buildings standing and the houses full of people shortly before its fall to the Germanii, but now there was not even a scavenging dog left alive in the ruins! He nearly wept, but he was too much a battle-worn warrior to do that now, and the civilized and pampered youth of Roman Britain was long dead in him.

Anyone along the main Roman roads of Britannica prospered, so not wanting to miss out entirely, Glevum mustered its modest strength and resources and went to work. The citizens of Glevum and her elders together financed and laid a fine Roman-styled pavement of five-sided stones from their city square to the nearest high road, thus joining the little world of Glevum with the major cities of Britannica's heartland.

It was a very big, expensive task for a small city, but nothing was spared and they completed it, without the emperor in Rome having to lay another tax on the entire province and send legionaires to finish it for them. How proud Glevum had been of their work--yet now nobody but the enemy tramped Glevum's pride and joy (which was set with milestones just like the ones on the imperial roads, on way to raiding some hapless village or other that had hitherto escaped or eluded their notice.

What were the evil Germanii intending in this latest raid? They had already ruined Glevum--there was not a stick of furniture left in it to pick and throw in the campfire! As he looked at the desolation, he could not see any way it would ever rise again--the people were all dead or enslaved to the Germanni, sold over in Gaul, dispersed and impoverished--for them there was no chance of returning to restore their shattered homes, shops, baths, stadium, courts of law, and churches. Fair and merrie Glevum was lost forever!

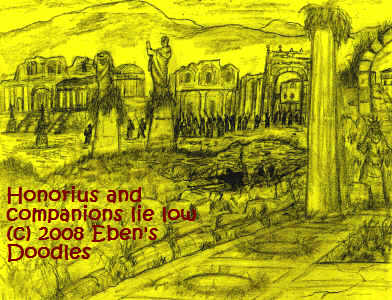

Terrified at the thought of being caught there and then made sport of by a whole army of barbarians, the three men ran and huddled in the ruins beyond the main square, hoping and praying they might not be detected. The cursed Germanii, however, often took along keen-nosed Irish bloodhounds, and if they had some with them on this foray, the game was up! They would be caught! But in a pinch, barbarians slit their dogs' throats ad threw them, hair and all, into their stewpots, thinking them very tasty, and so possibly this army of raiders, passing through a completely desolate wilderness of dead cities and burnt villas and ruined farms might not have any canine noses left to sniff three Britons out of hiding.

That was all Honorius could hope as he lay low with the others and watched the first Germanii march into view. He decided he would kill himself first, by cutting his own throat, before he let himself be made the butt of the Germanii's horrible, beastly, obscene humor--for they were known to torture their British captives in the most fiendish and grotesque ways imaginable.

Stuffing a man's severed fingers or toes or even his genitals in his mouth, or cutting off his leg to the knee and wrapping it around his neck like a Celtic neck band--they did not mind any form of cruelty just to get a laugh. That was ordinary treatment for any British man who fought them. If they captured a whole British family, this afforded them special fun. They would force the father to cut the head off his own son, daughter, and wife, after making him watch them rape them as the rest, waiting their turns, looked on, made jokes, and laughed. Only after that would they gouge out the poor man's eyes with a dirty knife, and then often as not they then turned him loose to wander sightlessly until he starved to death or fell into some deep pit or tumbled off a cliff. And at their feasts, they stuck their cook pots right on top the bodies of their slain victims, heaped up with plenty of wood.

Honorius and his comrades did not have long to think of such things happening to them. The Germanii, a mass of ceorls or common warrior footpads under the command of an eorl, a war-chief in their tribe, were approaching! They moved quickly, even in large groupings. The stench got worse and worse, and then suddenly the earth shook with the tramp of hundreds of feet, accompanied by the ear-splitting screech of ungreased wooden wheels and axles of ox carts that travelled in the rear of the raiders and brought along the loot and the war-chief's latest batch of concubines.

The man obeyed, and there were two left. Honorius turned to his companion and fellow shadow warrior, whom he knew would stand by him to the death. "Gregorius," he said to his fellow shadow warrior, "there is no need for both of us to die on this venture. You came this far, and I am pleased by your courage, but you might as well go back too. Alone in this enemy-occupied territory is best. Only when you think it is safe, join up with Plautus and help him the rest of the way should he weaken too much to make it back."

Plautus nodded, and--his reluctance to leave his leader showing in his expression-- left Honorius to his fate. Honorius left the ghost town of Glevum and turned toward the Urbani estate, but he made a round-about approach, as if dreading to see the villa again. It so happened he came upon a shepherd's hut he had completely forgotten that lay on the boundary of the estate. Secluded, nestled up against some trees and hills, it had not been molested by the barbarians who had obviously not seen it, or had not thought it worth burning.

Curious about it, wondering if he could find shelter there if he ever needed it, Honorius warily approached the hut and its wattle fence enclosures.

But instead of a dog, a woman's face appeared. She took a good look at him, and something in his appearance seemed to assure her he was not an enemy or a barbarian, for her wary expression changed.

She came out, and with difficulty holding the snarling sheepdog dog on a leash, tied him to a fence, then waited as Honorius slowly approached, ready to spear the dog if it got free.

"Who are you?" she said.

Honorius was taken aback. Where had this young woman come from--what was she doing in the hut of his estate shepherd? Was she his wife, or his sister? Impossible. The shepherd would have been killed if he had not run off first.

"Who are YOU"? Honorius demanded in return. "This is my estate, my property! I never gave permission for you to lodge here in this hut!"

The young woman's face seemed to ponder the fact, and then her mouth fell open and her knees gave way, and she knelt down. "Oh!" she said.

She rose slowly, peering at him. "You seem a decent, civilized man. You asked, so I will tell you everything. My name is Placidia of the Arbori family. I lived with my family in Aquae Sulis all my life. My father had a shop and dealt in purple and fine silks and brocades imported from Constantinople. We lived well, but lost everything, for we had no time to take anything valuable away or sell our shop and house. With only a wagon and horses to transport us, we fled south, but had to turn round on the road, for it was cut off by the barbarians. We then tried to reach Isco Dumnoniorum, where my father planned to find passage for us on a ship or fisherman's boat to take us over to Gaul. It was not meant to be. On the road to Glevum, we were attacked by another force of barbarians coming from the opposite direction."

She paused, staring hard at the ground, her shoulders shaking. Finally, after a few moments she went on. "My parents, sisters and brothers, with our household servants--of course, all slain. But I got away, by running up into the hills, and my pursuers did not want to waste time chasing one girl--so I got away.

I hid in the high hills and rocks, but I starved, so finally I came down to Glevum, and found it was all burned, and in ruins, and everyone gone. Yet I found some bread crusts and some other food in storage jars that wasn't burnt or all spoiled through, and this kept me alive, but I was in great fear, lest the barbarians return and catch me.

I wandered up here and found this little hut and the door left wide open. But I knew this hut and the estate had to be already in the hands of some warchief of the barbarians, for they no sooner take a district then they divide it up for their warchiefs, and each chief then parcels it out to his warriors to keep them in his power and for doing his bidding. Where would I go? I decided I did not want to leave my country after all. Either they let me live, or I would die here on my country's soil, I decided."

Honorius was astounded. "What did you do then? How in the world did you get to stay here, unmolested?"

Placidia smiled for the first time. "I thought of a plan. I knew the sheep had scattered when the shepherd ran away from here, so I went up into the hills and gathered some of them, and led them back here, and this lonely dog too came and joined me, and so I had something to bargain with. Then I set a fire, and waited. It wasn't long. The barbarians came with their chief to see who was burning wood."

Honorius could hardly believe his ears as Placidia continued. "I knew they would rape and kill me just as soon as let me remain in peace here, but I had these few sheep in hand, so I had something to bargain. Stop! I told them, for the war chief was able to understand some of our language. Then I made it known to them that I could keep sheep for them, if they would allow it. Did they have anyone to do that, or wanted to do that mean work?

"No, there was not one who wanted such low work in this fine new country they had just seized--as each warrior hoped to live like some fine lord in a great house very soon, with plenty of slaves to serve him and many women for his bed and pleasure. They all looked round at each other, it was so comical to my eyes, but I kept from laughing, as they are so simple-minded as brutes go.

"I had a knife, and so I showed it to the war chief, then pressed it against the big vein in my neck. "I will not let you rape me, and you will lose a shepherdess--so why not let me live, and not molest me as you have already planned, and I will do you this service?"

She laughed a little now, as she finished the story.

"I could tell the war chief was thinking, for he was rubbing his brows hard with his dirty hand. It was just as I thought--I had made good sense to the ruffian. The war chief hired me--for my life, and without being raped, he permitted me to keep his estate's sheep. I would have to gather them back here, of course, and he would take one out of five sheep each season for his table. The deal was struck, with one of their barbarous vows or oaths and the waving of their raven banner and shouting allegiance to their gods of vengence should the agreement be broken by either party, and they departed, leaving me at peace. I have my dog for protection, and he warns me of anyone's approach. He will die defending me and the sheep! And I have, best of all, the Lord! He is my strong tower and refuge. He has angels, mighty warriors, who are standing round about me in this very hut! So, you cannot do me any harm either--if you should be thinking of--!"

He lifted his hand toward the villa. "--is gone, there is nothing left, only a certain treasure--which only I know of. If I could retrieve it, I might become rich again, but the moment I am seen, they will run and kill me. No, I won't be able to dig it out for a long time, if ever."

She also began seeking something for him to eat. Her awkwardness in milking an ewe showed him at once she was a city-bred maiden, trying to learn country ways but not knowing just how to do things, having not been taught.

As a boy Honorius had enjoyed the full run of the estate, and being curious he had gotten into everything and observed most everything done by the workers and slaves. Now it came back to him, how best to care for the sheep and how to make oaten cakes and fry them, and many other things he had observed as a boy.

These things he now taught to Placidia, who received his instruction quite humbly and gratefully, so that it was easy to teach her everything he knew.

Together, they did well, and life improved quickly at the hut, and the sheep also fared well. Days passed, and the time went swiftly, and Honorius told Placidia how to find suitable ground and put in a garden (though they did not have the seeds as yet, and no ox and plow either) and also how to gather the wild oats and barley and wheat that was growing in the fields and would be maturing.

He had to talk to her, after he made up his mind.

"If the Germanii come, they might kill me. I cannot risk that. So I must go."

Placidia's expression told him all he needed to know.

He took her hand, and she did not pull it away. "Will you come with me?"

Her face showed her struggle. "But I can't leave my country! I know there is little here anymore--but still--"

"I want you to come with me, and be my wife and bear my children. Will you come with me now?"

Placidia walked away, and he waited, but he didn't see her return, so he thought that was the end of it. He started to gather his things, what few things he had, and when he saw her return, he told her what he had to do first before he departed.

"I've put it off till now. I must go and first bury the bones of my father and mother, and sisters, and the others if I can--this is my last duty to them."

Placidia took hold of his arm. "But the Germanii would kill you if they find you there."

"I still must do my duty by them. I just could not face their bones until now. I cannot leave until they are laid to rest."

He had his title deed, and the seal ring, and his weapons, and he started walking. "Wait for me!" she said. She came back to him, wearing a cloak, and she had sandals for herself and another pair for him.

"Yes, Honorius, I will go with you and be your wife, but we must find a priest first."

He nodded.

He kissed her.

"What about the sheep? Are you just going to leave them?"

She smiled. "I wouldn't worry. The dog is faithful and will watch over them. I have left the sheep in the pasture, and they will be safe with him. The war-chief is due to come to inspect in a day or so--and he will find me gone and see to the sheep.

So they were free to go! At the villa ruins, Honorius left Placidia and went forward to where his family had been hung up on the cypresses.

It was a horrible ordeal for him, but he was a man now, he had seen death and dead men's bones often enough, and he managed to gather the bones and move them to a place beneath an oak tree. There he dug a shallow grave with a big stick, and laid the bones to rest. Before he pulled back the soil, he put in the title deed and his seal ring.

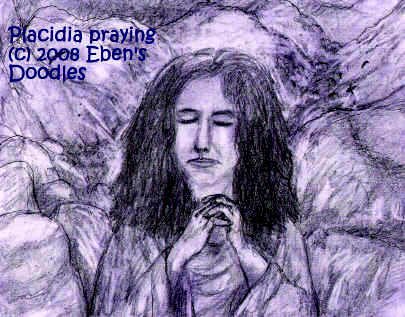

He would have said a prayer like a priest would say at a grave of a Christian, but he did not know a prayer for that. Placidia's voice startled him, however.

She was praying, he realized, kneeling as she did so.

But he also realized her words were not for the dead but for him. He began to weep. It was all he could do to stand, and then he moved away.

Placidia joined him, and together they let the estate and the life that was lost forever, not by the road, but by the wild countryside that led up into the hills and the mountains.

They climbed for some time before Honorius paused to let Placidia rest, for she was gasping for breath.

"Are you in such a hurry?" she said.

"At this pace you will kill me!"

Honorius sat down on a rock. "No, there is no need for that. I wasn't thinking. I just wanted to get away, as fast as possible!"

Placidia did not comment, but looked at him, and he glanced at her, feeling her gaze. Then he went to took her hand, and his head went down and she lay it on her lap. For some time they sat like that, and she said, "Do you know where there is a priest for us?"

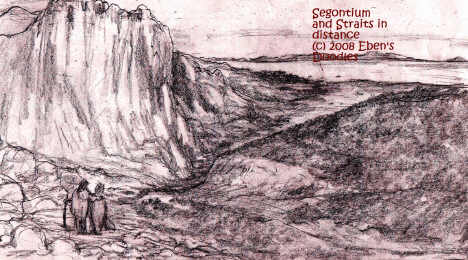

He glanced up at her. "I will not dishonor you. I know where one is. But it is a journey of some days. But we will go there. To the city Segontium, where the sea is, and the straits that lie between Segontium and the western island. Rome once supplied the city generously, but no longer. It has grown poor. Yet the city has a church and a priest, and there is a big stone fort from the time of Rome, and though it is not garrisoned, the city still has not been taken and plundered by the Germanii--the tribes round about it are yet to fierce for the Germanii to attack, and there are many Britons residing there too. Perhaps they heard there is no gold there these days--whatever the reason, it is a good refuge still. Perhaps you would like to live there?"

"I don't know. At least it is in our own country--though barely! Do they speak our Roman language?"

Honorius looked at her keenly, then said, "Very few do anymore! Times have changed. We msut get used to that. But it is not in my heart to remain there, evenso."

"Where would we live then? Over in Gaul? Surely not there! And if it is Erin--you might as well leave me here! They are all heathen savages over there, serving foul idols and always fighting and drinking and--"

"I will tell you later, in Segontium!" Honorius, wisely, said, interrupting her. "But first we must find my comrades and warriors in the hills where I left them last, so that I can appoint them a leader and grant him my authority and blessing. They will be wondering how I am faring--and I cannot leave them without their knowing all is well with me--as well as it can be in this time.

His name, they found out, was Patricius, and he was British, not Irish.

Another surprising thing they learned from speaking to him--he had been born and raised in a small city not far from where Honorius was born and raised. It was a marvel to Honorius, and he could not quite grasp what it was that was tugging at his heart so strongly. But the evangelist seemed to know, for he spoke gently to Honorius, "God is calling you, son! Let my servants go tend to your farm and livestock, for I know you are thinking about them. Tarry with me and my company a while. You will not regret it, for God's blessing is sure when He calls a man."

As long as they could, they remained with Patricius and soaked in his messages as he preached day after day to the heathen Irish, converting many hundreds of them and baptizing them in the rivers and lochs.

A day came when Patricius himself wanted to be baptized, and went with others into the river.

Placidia followed him. When it was their turns, Patricius questioned them separately concerning their faith.

First, he dealt with Honorius. "Do you believe the Christ, that Jesus is the Son of God, the Savior of all men, and the Savior and Lord of your own soul? What say you?"

"I believe, but I have sinned," Honorius confessed.

"What is it, son?"

"I have hated the Germanii with all my might, and taken revenge on them whenever I could, and my heart still burns with anger toward them. I could never forgive them. So I have killed them, even women and children when I could, just as they killed my father and mother and my sisters!"

"But you must forgive them, or, as Christ says, he and His Father in heaven cannot forgive you!"

It was the most difficult thing Honorius ever did, letting go his unforgiveness, and forgiving the Germanii. But feeling the fatherly love of Patricius, with Placidia's loving presence at his side, Honorius forgave, and found instant release. Instantly, a burden like a cart load of Roman bricks was lifted from his shoulders. He felt as if he were born again, and his spirit had spread wings. He felt he could almost fly--he felt so light inside!

With joy he turned to Placidia, whose eyes mirrored his own expression.

Together, they left the water, and climbed up on the grass of the bank, both changed and never the same again.

Later on, when Patricius came again, there was a meeting of believers in Christ in Honorius's humble dwelling, all there because he and Placidia had been telling their neighbors the Good News about the One who forgave sinners, even while He hung on a Roman cross, suffering for their sake by paying the penalty for their sins.

These people all wanted to be baptized as well, but Honorius said that would have to wait until Patricius came again. And then there he was, just when the new child had arrived, with all his people and their wagons and tents! It was as if an angel had carried Honorius's words to the holy man!

Patricius called Honorius and Placidia with the baby in her arms out to him, and before all the church members appointed Honorius a deacon and his wife a deaconess.

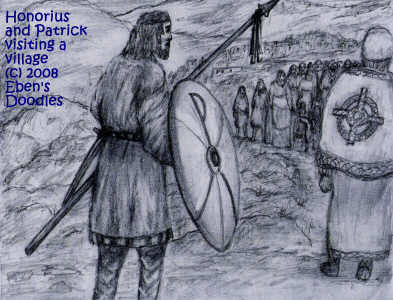

But this deacon could fight. He was a warrior before he was a farmer. And so Honorius often accompanied Patricius on many visits to heathen villages and encampments of the tribes, his sword and spear ready for dealing with any assassin sent by the hostile Druid priests to stop the Gospel-bringer.

Honorius was a happy man, blessed with a church, wife, and family, and was honorable in all his ways. He forgot the almost mind shattering sorrows and misery of his war-ravaged, occupied home country, though he still cherished her in his childhood memories. He gave up fighting the ones who had conquered and colonized his beloved Britannica--realizing it would not be restored as it had been. Yet he lived to see his grandchildren return there--a last joy on earth he had not expected--as they carried the light of the Gospel of Christ to a heathen barbarian people, faring out from his own church and others, to Dark Kingdoms of the Angles and Saxons. Within a few years the heathens were flocking to the Cross of Christ and smashing down their pagan altars and idols with stone mallets or casting them off cliffs or consuming them in the fire. They knew a better thing when they saw it--once their eyes were not so clouded by lust for land and wealth that they could see their true state, their sins and needy souls' lost conditions.

The supernatural miracle had occurred of rebirth and new life from ashes. Though once speared and cast in the fire and utterly consumed, the Phoenix of Britannica had returned risen and triumphant and glorious, flying from Eire...back to England.