The German Kaiser (Caesar) was a bombastic militarist and martinet, and despised peace as a sign of weakness. He was the sort of vain fool who loved to show off his power and splendor.

He had his generals organize immense military parades of his latest Krupp artillery and when receiving dignitaries from other countries he wished to cow or impress he walked them down a corridor made by two rows of seven foot tall blond giant specimens of German manhood all dressed in blue like Greek gods, who stood blowing golden trumpets loud enough to split the visitors’ eardrums. How Queen Mary, his cousin from Romania, objected to the trumpets’ blare—yet he only added more trumpeteers after her departure in disgust from Berlin.

Thanks to him, Germany charged full-steam ahead in an arms and shipping race with England that almost certainly guaranteed war. His ally, Franz Josef, ruled a polyglot, backward, militarily-indefensible hodgepodge of principalities and nationalities who were always seeking to break from his empire.

A grasping old spider who thought only of imperial honor and advancing his borders at the expense of weaker states, Franz Josef enjoyed Berlin’s full military backing, if not Berlin’s high admiration. Together, the old man joining with the vigorous, if empty-headed younger man, they were sufficient to turn Europe upside down. It only took the provocation of a single incident—the assassination by the rebellious Serbs of the Austrian Archduke Ferdinand—to ignite the world war.

Britain and France, allied against Germany and Austro-Hungary, fought four long years of trench warfare, suffering the poison gas attacks and the “Big Berthas” of the Central Powers, losing nearly a whole generation each before America entered the war and turned the scales against the Germany and Austro-Hungary.

“The War to End All Wars” it was called, and American doughboys sailed to the battlegrounds of France with that hope in their hearts. When Germany, after seeing that victories over the unprepared, inept Imperial Russian armies in the east would not bring victory on the Western Front against the American-bouyed Allied Forces, capitulated and sued for peace, the whole world, it seemed, thought that a millennium of universal peace was just then gleaming on the horizon.

Wild with love and hope, the war-weary French populace greeted the peace-proclaiming President Woodrow Wilson and his lovely, elegant wife, come to attend the Armistice conference to be held at Versailles, France. He was their Savior from centuries and millennia of almost ceaseless conflict and wars of aggression and greed, that had devastated Europe times beyond number-—or so they imagined.

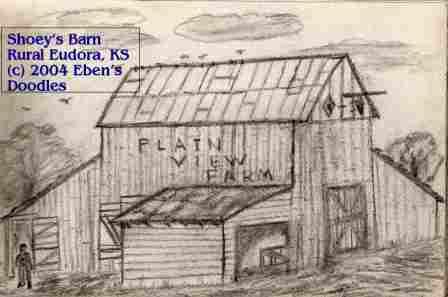

Without a single clew in Kansas that everything was going wrong in far-off, foreign Versailles, the routines of the rural Eudora, Kansas, farm founded by an Exoduster, William Washington Shoey, continued without change. It would be years, in fact, before anyone heard of yet another troublemaker on the European continent—the young Austrian Adolf Shickelgruber who would raise the Swastika banner above his volunteer army of brownshirted supporters.

What did the vast prairies and backwaters of Kansas know about world war anyway? The sands of the prairies had once been covered by a great, inland sea that slowly, slowly receded, leaving only the sand and a few shoreline cliffs of eroded limestone. Across that sea bottom grass had sprung up, producing feed for millions of bison until the white man’s coming. He quickly swept them out of existence and planted farms and towns and cities. The whole area was fenced, provided with roads and telegraph and electric poles, and railroad lines connected up Kansas with the whole of North America and the major markets for corn and wheat, Chicago and New York City.

Yet war and bloodshed came to Kansas—a foretaste of it, perhaps—in the so-called “Shadow War” when slave-holders and anti-slavery forces battled it out for the control of Territorial Kansas before statehood could be declared. The slave-holders won, temporarily. Kansas entered the Union as a Slave State. But the South was defeated in the Civil War. Free and rejoined to the Union, Kansas flourished as never before. Pouring out from the cities in the East, settlers traveled in a steady stream of ox-drawn Conestoga wagons to new opportunities in the Western Prairies and in the territories stretching beyond to the Pacific Ocean.

William Shoey was no white man, but he wanted all the white man could achieve in a free land, and so he took his savings and wife and joined the vast exodus from East to West. His hometown, St. Louis, a gateway city to the West, was most convenient. He didn’t have so far to go, as others before or after, who set out for territories like California and Oregon. Yet for Shoey, a city bred young black man, it was a leap into another world, to leave the big city and plant his tent in a wilderness where there weren’t any paved roads, streetlamps, running water, sewers, stores, hotels, and factories. He had to learn everything from scratch, scratch, and more scratch, unlike so many who left little farms in Eastern states and knew more or less what they could expect in the West as they carved out new farms for themselves from the virgin wilderness.

Motorized vehicles, steam cars and also gas-fueled horseless carriages, were just then showing up in St. Louis’s broad, brick-paved thoroughfares when William Shoey and his wife started the farm on a property he bought outside Eudora. In the midst of so much empty ground, it looked as if no modern thing would ever make itself seen there as he set out with horse and plow to turn the virgin sod. If he had started out sooner as a pioneer on the Oregon Trail, he could have gotten the land in Kansas for nothing but his signature, but he wasn’t old enough then to do any such thing. Now he had to pay for everything, but he was willing to work, wasn’t he? It was better late than never! He thought.

Hard worker that he was, with his wife’s steady contributions, the Shoey farm quickly took shape, as the barn and house were built and the fields plowed, planted, and harvested. The barn was maybe half the size of his mainly Amish neighbors and wasn't painted, but it was still a barn. Amish neighbors, who all had red barns, clucked their tongues as they drove by in little, black wagons. Yet how proud he was of it! The house, which he thought little of, being the product of a carpenter friend’s expertise, didn’t compare to the barn in his estimation. Not the house, however fine, it was the barn made a farm a farm! All his hard work, dreams, and Bessie’s faithful prayers had managed to produce a barn worthy of the Shoey name--not to mention countless loads of scrap lumber he had managed to wheedle out of the lumberyard in town, plus the wood from shanties of the first settlers who had moved on. Even if “Plain View Farm” he painted in large, white letters on the side facing the “road’ leading to Eudora.

He never tired of looking at the farm’s name emblazoned on his barn.

Yet this Exoduster, smart as he was, hadn’t figured on one very important thing, as it turned out. What was it? The Armistice turned sour, very sour, over in Versailles, France, which would give a certain Austrian corporal the pretext for re-starting the world war that exhausted combatants had temporarily given up fighting. Without a subscription to any St. Louis papers, Willy could be excused for not knowing that, of course. Besides, old Europe with its continually feuding kings and emperors was far away, and there was a mighty, big Atlantic Ocean between America and Europe. The oceans were America’s protection, better than the mightiest fortresses Europe could boast. America, as long as the oceans didn’t dry up, was safe. At least that was what all the immigrants thought when they sailed into safe haven in New York’s great harbor.

And where couldn’t it be safer than the heartland of America, deep in a place called Kansas? There the only thing you might worry about was a rough winter or an occasional drunken vanilla ‘n’ spice salesman--or so William Shoey, like millions of other Americans, thought.

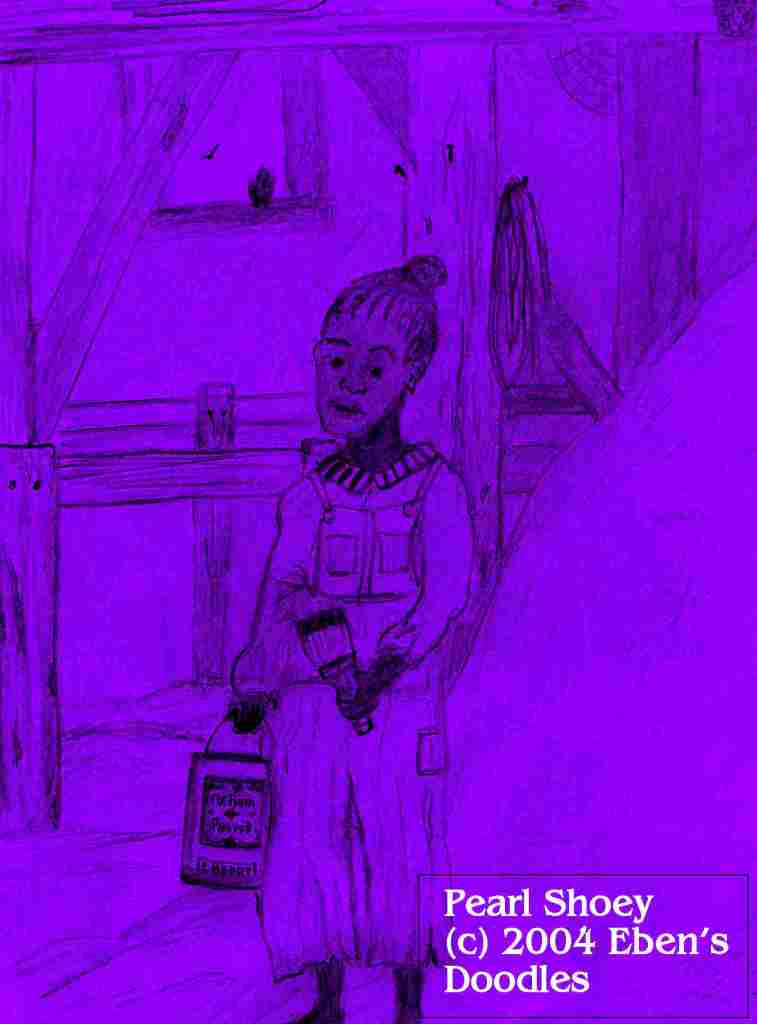

“I’m going to get holt that red barn paint Pa is savin' for the next barn, and a brush,” she thought, “and see if I can’t catch ‘em by opening the door partways, and when they try to squeeze through and can’t make it I’ll put my foot right on them and paint them.”

It seemed the perfect plan, since she had heard from her Ma that if you were quick enough you could paint rats red and they would run away from the farm forever and leave their corn alone.

She rummaged around in a corner of the barn where her Pa kept the wagon and also gear for hitching up the horses and found the special barn paint. There was half a can, along with a well-oiled brush. Wiping off the oil on a post, and after prying off the can lid with a big nail, she was ready for the rats.

Sure enough a flood of frightened rats began pour out of the door where she stood crouched. Before they knew what happened, she painted each and every one before it could get away. It would only work once, she knew. Rats were very smart critters, and they couldn’t be surprised twice in the same way. She had to get every single one the first time, she knew, or it wouldn’t work—they’d be back, following their leader.

Spashing paint all over as she dipped into the can as fast she could, she painted until no more rats appeared, and then she let her brush drop. She had done it!

Just then, she heard her Pa call her name from the entrance.

“Pearl, what you doin’ so long in there! Ma wants you back bad at the house to help with washin’ and ironin’. Pearl! I’m not calling you again! Out you come now or—“

Without a chance to wipe the paint from her hands and arms and face, Pearl went in, hoping for a a commendation for her good work, but she ran right into a frightful scowl.

“Oh, look at you, girl!” he cried. “Playing with the paint I was savin' when you should be workin’! Your clothes are ruint! You are asking for a birch on your bottom, little missie! Now what do you have to say for yourself before you git a lickin’?”

“But—but—“ she began. Yet how was she going to explain it? Didn’t he know that painting rats red was the way to get rid of them? Grownups were supposed to know everything.

“I just thought I’d help you get rid of the rats,” she said lamely, her voice trailing off to a whisper.

Willy stood there, his arms crossed, baffled.

“You painted the rats, girl? Is that what you did with my good barn paint? I just can’t believe it!”

“Yes,” she said, beginning to cry. “I painted ‘em, so they wouldn’t come back and gittin' our corn!”

Willy was stunned. How could his eldest be so dumb? He thought. He grabbed a stick and was advancing toward her when something shot into the open doorway.

Pearl’s eyes were just about to drop to the ground in shame and mortification over the coming punishment when she thought she saw a kind of sparking star sail up and around, then sideways above her Pa’s angry head.

Years later, Pearl still hadn’t forgotten the licking her Pa gave her for wasting good barn paint. And she had never found the courage, even when she grew to adulthood, to remind him that the rats had disappeared completely just after she had painted them red. In a day they were all gone! There wasn’t a rat in sight on Plain View Farm, because all the rats were afraid, just scared to death, by the red paint on each other. They literally chased each off the farm, so they never had any rats after that.

It made her laugh some to think about, though the beating never set right with her, since she had not intended to waste Pa’s paint but had actually helped him. What concerned her more was the second thing that had happened that day—-the appearance of that strange, little red star.

What in the world was it? Where had it come from? It had flown in out of nowhere and then vanished from sight before her Pa got to see it, but she couldn’t get it out of her mind.

It was from that day, she knew, Pa had begun to change.

It wasn’t a stranger who took his place. Was it the little red star that changed him? They felt so safe on Plain View Farm, a wonderful place where no harm could ever reach them.

Yet nothing she could think of could explain what happened to her beloved Pa after the visit of the little red star.

It was such a pretty sight in the dim light of the barn—-how could anything so pretty do anyone harm? Because it was connected with the rat-painting incident, she eventually came to call it the “rat star.”

It was just as red as she had painted the rats, wasn’t it? Only it shone like a star would shine, only none of the stars in the sky ever moved like this one had—-it was more like a living thing—a rat, in fact!

It had the same movements of the rats, quick, nervous, darting, pausing still, then vanishing out sight! Would it ever return to Plain View Farm? She had wondered from time to time. But somehow she didn’t want to see it again—-not since she noticed the great change in Pa.

Coppyright (c) 2004, Butterfly Productions, All Rights Reserved