O F

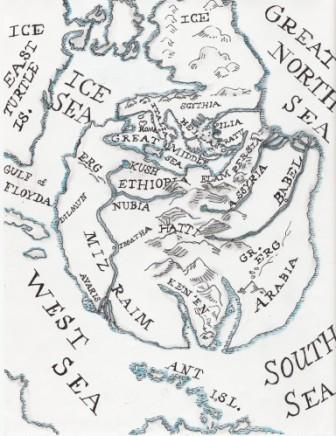

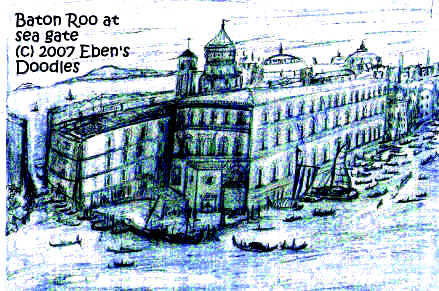

T H E

N I G H T E N G A L E

The triumphant new religion that swept up through both halves of North America was Isma, and the Ismanic armies pushed all the way from Atlantis II to the snows and ice of the far north. Baton Roo, though founded by mostly Scandinavians turned back to their ancient Viking ways, was added to this and that empire on the mainland of East Turtle that included Georga or the revived Confederacy's empire centered on Kingston (later called the CSA). Growing more powerful and rich, Baton Roo succeeded in throwing off the mainland's control, and beat every navy sent to reconquer them. Independent, Baton Roo flourished, not longer having to pay stiff tributes every year to far-off sultans and emperors--and now could concentrate on its own empire-building and the extension of its trade network, the Baton Roo League of cities.

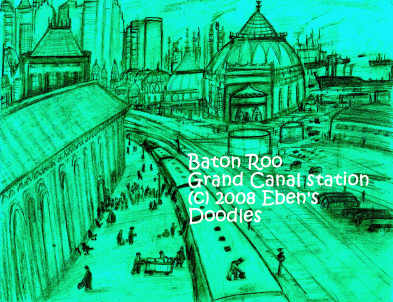

The warm sea of the straits between East and West Turtle Islands became Baton Roo's own sea, and everything passed in trade passed through Customs at Baton Roo or the tariffs were paid to Baton Roo naval patrols and warships. A warship a day was turned out on the fast production lines of the Arsenal, the city's naval complex. No other rival could equal Baton Roo's navy or hope to penetrate her naval defenses of huncreds of forts strung along the straits and also situated on every considerable island. With its warships and navy, Baton Roo reigned supreme and entered upon its Golden Age.

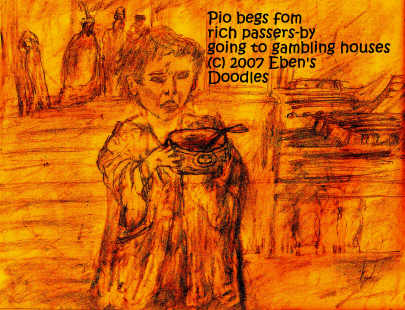

In a city so rich and powerful and greedy as Baton Roo, the rich and the ruling class became corrupted and arrogant and heedless of the poor, however. State charities did not help the many poor in the city, despite the vast amount of congratulation given the grand donors to the charity at the various state balls and festivals staged for the benefit of the poor beggars and the homeless living along the canals (for the city did not have paved streets, but utilized canals instead). The major, marble paved squares were also places where the poor were found, because they could hope for a bare living by begging from the rich passers-by.

Pio was one boy, looking like hundreds or thousands in Baton Roo who kept body and soul together (at least temporarily) by begging.

Sometimes though, whole days of hard work at begging passed without a piaster, and the beggars starved, or they went to the markets and begged cast-off, half-rotten vegetables or fish beginning to smell bad and turned unsalable--and sometimes that kept them until times and hearts melted and turned more generous. Festivals were good times (not that they received the monies donated to the poor, for they did not), because the watching crowds at the royal regattas were more open in their pocketbooks than during the usual workdays, when they had to think of their own expenses and the high taxes the governmemt of the city's ruler, the Doge, imposed on them without any vote ever being taken.

When Pio was seven (and was small and younger looking for his age), his father took his day's earnings and then, spitting in disgust at the few paltry coppers sandwiched with tin that were minted in Gorga, a backward principality on the mainland, announced that he could no longer afford to keep him. He was to launch forth on his own! This was the most crushing thing for Pio. Abandoned to the wide world, which did not love him, by a father who did? Blind Giovanni loved Pio, his motherless son, in his own way--though he had not known a loving mother himself. It was better than nothing, knowing that you had a father. But now Pio had neither mother nor father--he was orphaned! Cast adrift on the vast and hostile sea of life!

Pio had no way to support himself except by begging, so that is what he did. He slept in a corner of some abandoned building, then in the morning crept out early (to avoid the city police who were hard on transients squatting in abandoned buildings) to the nearest public square or stationed himself by a special event going on, to catch the passers-by who were merchants or traders or ship owners with purses bulging with gold ducats.

But the highly refined aristocrats of Baton Roo heartily despised beggars--so this was not a way for Pio to get much of anything for his growling stomach for that day.

Into the man's boat he stepped, and a new life opened up for Pio immediately.

He was the boatman's helper now. He did all sorts of little errands for the boatman, whose names was Luigi Tuscany Bonaventure, a grand name to the beggar boy's ears. The boatman also seemed very rich to Pio, as he not only wore a velvet brocade coat, but a velvet hat as well, and he had the same sort of outfit for Pio to put on, so that his rags would not turn the boatman's paying fares away in disgust.

Not usually cruel to Pio, verbally or physically, Pio did not take him seriously enough perhaps. He sang, but without much heart or enthusiasm, and sure enough, Luigi, who was bad-tempered because of his hurting shoulder and arm, added to his cold and lack of singing voice and the loss of tips, grabbed the less than profitable, mediocre canary and into the water he went! Pio was a drenched and sodden mess when the boatman hauled him back out of the filthy canal with his boat hook.

"That'll teach you," rasped the boatman. "Now sing like a sweet canary of the Doge's, or over the side you go again!"

Pio was now very upset, and crying, but, having perfect pitch without knowing what that was, he tried his hardest to keep his notes from wavering and going sour or off-key.

With the next passenger, he did not do as well as he wished, however, and again no tip. Luigi was now in the mood to take out his spleen and frustration on the only person available--the poor little green and red-tinged tweeter he had on board. Into the dirty water bath Pio went again! Sputtering, water coming out his nose, Pio was hauled back aboard eventually, but the boatman would not relent and grant him any mercy.

"We will both have to beg in the streets, if we don't get more tips today. The fares aren't enough to keep both of us in bread. So sing! Sing your heart out this time, boy, or I'll drown you yet! You'll not get away! I'll hold your head under like a puppy's until you're done for, and nobody will give me so much as a curse--they'll all say good riddance to you, you worthless baggage!"

Luigi was not stretching things. It was a hard life, lived by men whose hearts hardened according to the circumstances they could not avoid--and who else but orphan boys like Pio were made to bear the brunt of the suffering and financial distress their betters could not escape? Trying to keep back the flood of tears, frightened nearly out of his wits, for he felt he was wet enough, Pio tried to do better.

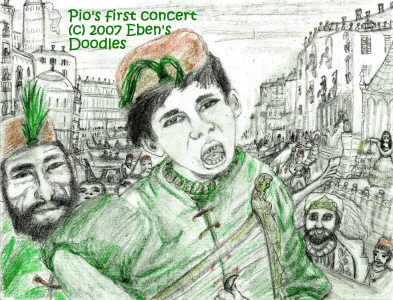

This time he was so terrified by the inevitable dunking he knew was coming, that something snapped in him, and he really did sing from his heart, only in a way that startled everyone within earshot. Too flustered to be able to call to mind the words of the songs he had learned from Luigi, he began singing extempore, or calypso style, songs that nobody had ever heard before. Pio himself, being so young and inexperienced in life, did not know he knew the things he was singing about, but he had to sing something, and these songs just poured out of him like a river--they could not be restrained. His voice too snapped and became deeper, and the volume increased tremendously! He could be heard for a long distance, and people everywhere were turning their heads to see where the nightengale's wonderful music was coming from.

Then the lyrics, created on the spot, were astounding, and perfectly matched with the tunes. They created the very scenes that the city was known for, yet did it in a way that told stories, stories of melancholy, confused youth, of lost love, of violated innocence, treachery betweeen bosum friends, betrayals of misplaced trust, of base greed and lust for wealth, of ambition that climbed too far and fell to the depths, of hopeless lives, of misspent talents, of drunken, self-destroying lives, of many, many things that make up the warp and woof of the taspestry of life in a great but very worldly, wicked city such as Baton Roo was. Beautiful, tawdry, glittering, deceptive, seductive, poisonous, and deadly--all the threads were there, the gold and the fool's gold, the muslin and the satin, figured silk brocade and callico cotton, the paste rhinestones and the diamonds, the glass beads and star sapphires, all mixed together in the pattern.

His master, gaping at the boy wonder as he performed, was kicking himself, however, mentally cursing himself for almost drowning the songbird, which was his right to do as a slave owner. How could he have known this poor singer in the past was capable of emitting such beauties as were pouring forth from his little throat? And where did he get so many songs, and how did he put them together, changing them into much better ones, like he was doing, right on the spot? The little ninny could not possibly do such things--but there he was, drawing thousands of important people to listen to him, and the whole rest of the city was coming to join them--for Luigi could see a crush of boats trying to get to them in the already boat-choked canal!

The city came to an absolute standstill. Nobody could do any business. They all had to listen. The people were bewitched by the incredible, angelic voice pouring forth from this little boy nightengale in their midst, and the boats of all kinds with every class of people gathered by the hundreds round Luigi's, and he could not move as they all listened enthralled to Pio's first concert. The repetoire seemed almost endless, but Luigi, seeing a fortune of gold ducats falling like a golden shower into his boat, realized that he had better save the songbird's voice for another, rainier day than this, so he clapped a dirty gloved hand over his songbird's mouth, then against the roaring and catcalls and protests and curses of the crowd, pushed and oared his boat free of the others and made it back to their lodgings in a cheap inn on the outskirts of Baton Roo, nearest the seagate where the warships and merchantmen passed in and out of the city.

Luigi took some wadded up cheese and bread from his coat pocket and threw it to the crying boy for his dinner, then broke out a bottle of watered, vinegarish wine, gulped half of it down, and thanked his lucky stars (and the Prophet of Isma too for piety's sake) for not having drowned Pio like a gutter rat as he had thought to do, he had been so disgusted with him and the cost of keeping him.

Then, lo and behold, the half-drowned rat, some canal whore's little bastard, became a gosling laying golden eggs, right before his eyes!

As he counted out the gold ducats he had scooped from the boat into a big sack, they looked to him big as goose eggs, since he had never handled solid gold ducats before in his life--only a debased silver florin once in a blue moon.

How long would his little golden-mouthed gosling lay such wondrous eggs--for five years until Pio would turn twelve? Until his voice changed to a man's? What then, oh sweet devils of heaven? Luigi's narrow eyes squeezed almost shut in the gloom of the cavernous chamber (which had been a sea baron's harem in better days), and rubbed his thick, coarse beard as he wondered about the future.

But five years was a good amount of time to gather more such gorgeous eggs, he concluded, finishing off the bottle with a sour belch and a couple hiccoughs and forgetting all about spending a ducat or two of his windfall, sending some lounging fellow outside in the square to fetch him a twelve course meal fit for a king--and Luigi's thoughts whirled with the riches he saw cascading down upon his open hands like a golden river of Ophir.

No, you old whoremaster, he thought, he needed to keep close watch on his sweet-tongued gosling--and let no one near him--not that night anyway, lest he be snatched away by the Doge's men in the crowd. As for forthcoming concerts, there would be plenty opportunities, doubtless, in the coming days!

As he lay on the floor on his filthy pallet left there by long dead canal whores, Luigi fingered his splendid, freshly minted ducats with the Doge's own hook-nosed image stamped on them, counting them over and over, and scarcely got a wink of sleep that first night after Pio's grand debut.

As for Pio, he soon stopped crying over Luigi's unusually rough treatment and squatting on his pallet he devoured the cheese and bread, which was a bigger portion than his master usually gave him for dinner (for usually Luigi ate all the cheese). With such a banquet in his belly, he forgot the concert in the canal and his new voice--which he hadn't even imagined he had in his throat--and fell back asleep on the dirty, pillow-less pallet on the floor, exhausted, still wearing his sodden clothes.

Meeting with unexpected mercy despite his resistance, Luigi was left with his windfall of ducats (which would keep him comfortably for years, if he didn't throw them away on binges of wine and parties with whores living along the Love Canal, lighted up with red lanterns at night, where they were allowed by the city to ply their trade with sailors and merchants). But they took Pio against Luigi's protests, removing the wet coat and wrapping the half-delirious boy carefully in blankets and a cloth of gold and carrying him to the waiting Grand Marshal's gondolla for a quick trip straight to the Doge's palace and the Doge's own physicians.

She was also wearing her masque, which was required for all proper women going about in male society. As long as her appearance was made ugly and anonymous with a masque, she was allowed her freedom outside the palace harem.

She inquired of the boy's chief physician and his maids about him, his father and mother, his former home, and other particulars. Learning that he was a vagabond's son, abandoned to the boatman's care, with no mother to care for him (being one of the lost women who work the boatmen and gondoliers and such for their hired charms), she had pity for him and wanted to do more for him (for she was tender hearted).

His golden-throated gift was the talk of the town, and when she saw his care was very good and his improvement was excellent, she wondered if he could sing again. When she asked him, he did not seem to know he could sing. Pio did not even know who was his visitor, except that she looked like one of the grand ladies he occasionally saw stepping into golden gondollas as they left their palaces at rare intervals to go and visit a lady at another palace in the city.

That she was the Doge's chief wife was beyond his understanding. He did not know the city's supreme ruler was the Doge, much less than this was his chief wife appearing in his own bed chamber.

Pio knew he was in a palace, but whose? Nobody had told him yet, fearing to say anything lest it would be the wrong thing to tell a child just recently plucked from the lowest levels of society. Nobody could understand, among the servants particularly, why the Doge had even admitted him to his own palace. Such a thing had never happened before, they all knew. Comnmoners were never permitted, unless they came as servants or slaves.

As guests? unthinkable? Perhaps, the boy was a special slave, brought in to entertain? That seemed most likely to these unimaginative, fear-driven minds.

Grand balls and festivals were frequent in the Doge's palace, though the Doge rarely attended them. His wife, however, did not miss any opportunity to leave her cloistered existence in the harem, being young and loving life--such as a wife of the Doge was permitted to indulge, that is.

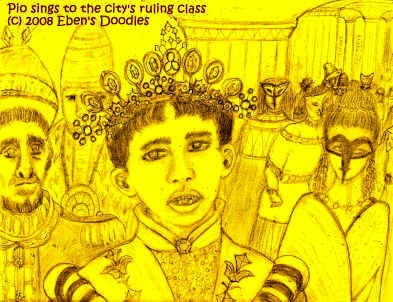

One day, the maids brought Pio some splendid clothes, took away his other garments, and bathed and dressed him properly. A royal-looking diadem was added, after his hair was most carefully washed, trimmed, scented, and combed. He had been treated to the best the palace had to offer, and did not object, as he had never experienced so many wonderful things all at once. His cold gone, Pio looked forward to leaving his bed chamber and re-entering the city he had always known--not just the palace, large and grand as it was. Bred, born, and raised in the open air, he needed the air and light like any wild creature.

But he was mistaken, for he was not taken out into the open air of the city and put in a gondolla. He was instead escorted with much pomp into the large hall of state, reserved for balls and receiving foreign ambassadors. A great celebration of some kind was in progress, even Pio could understand, when he saw the hundreds of people, all dressed like royalty in their silks and jewels. Strangely, they turned at the announcement of his coming and became very quiet, as he was led in by the Palace's Major Domo and the Chief Eunuch of the Harem and a group of palace guards. No one made any noise, and Pio was given to understand by the Chief Eunuch that he was to sing anything he cared to sing.

Having planned nothing, which was perhaps a good thing, Pio obeyed just as he had obeyed his master Luigi and opened his mouth as the hundreds of the city's richest and most powerful people waited in a dead hush.

All wondered, would he sing divinely as before in the canal, when all the city cast aside whatever it was doing and rushed to hear him before he fell silent? No one who had heard him then was disappointed. It was the voice of a century, everyone acknowledged, as though the city had kept track of all the singers of the past. Yet no one could remember anyone this great--so perhaps it was true, he surpassed any great voice of previous times, being greater than all his predecessors in living memory. Or had he lost his voice, being sick, as everyone knew from the tales passed from street to street by the gondoliers and boatmen as part of their trade. What a pity that would be!

Would the Doge and the whole company gathered at his invitation be robbed of the night's chief entertainment, the singing of a boy nightengale? The cynical, hard-hearted city waited, not expecting a second miracle--but still hoping against hope, having rushed here to the palace just for the slight, very slight possibility that one might indeed witness a repeat of the previous performance in the canal.

Men or women, it made no difference. High or low, aristocrat and prince or servant or palace guard--Pio was singing directly to their hearts--somehow turning a golden key with his nightengale voice and wondrous ability with music and words to speak to them in a way nobody else would be allowed or even think to do.

Unconsciously, unpretentiously, unplanned, Pio sang on, transforming the evening into an enchanted space of time where all else pressing on people's minds was clean forgot.

Pio's gift had given him the city's poor and the commoners, and now it gave him the hearts of the rich and powerful. He won them utterly, and they lay surrendered in his hand, listening to every word and note, unable to find one flaw--for his performance was a masterpiece.

Was he present? Yes! Casting aside any fear he had of assassination at a crowded, open public gathering like this, he had come down from his private apartments to hear the nightengale in his charge, and he knew immediately he was not disappointed. His physicians would be richly rewarded, for he could tell at once that the whole gathering was greatly pleased with the boy wonder's singing. Indeed, this boy had proved to be a fitting decoration to the ducal court!

But as he paused to listen, drawing near to Pio though standing off behind him, he began to realize that this triste was not the ordinary kind at all. It was merely a form the boy was using, however he did it, to spin a most remarkable national epic of some kind, which had never existed before, the Doge knew.

Where was this piece going to end? Victory, or defeat? The boy was singing of great war on the horizon, and peril, and picturing the warships going forth to assault the enemy in the south--but to what end?

Surprised and a little disturbed that a mere child could concern himself with the affairs of state (and how could he know them so intimately in detail?), the Doge listened all the more intently, trying to determine which way the song would go--for he was beginning to be a little unhinged by the portents and signs in the song, and that a little boy such as this could capture the city's soul so completely he could speak to the chief ruler and leading people of the realm as though they all were but a foolish child that needed instruction of some kind!

How dare anyone, a subject of the Doge no less, presume to do that? But this boy sang so angelically, all was forgiven, the Doge, looking about for reactions could see, and it was thought no presumption by the assembly--as the words were perfectly suitable, and the portrayal of the city's armada sailing forth to win gold and glory was most exciting and beautifully accomplished. It was thrilling to the Doge, moreover, to hear the might of the city, which was its great navy, pictured in this wonderful way, and the arms and cunning and warcraft of the men and their leaders, epically drawn as if he were the greatest poet and they all were engaged in an epic struggle of good against evil, and wisdom against folly.

It came forth, and the Doge turned pale as he listened. He saw his own black heart exposed and hung up for the world to see! He also saw the fruit of his follies--the glorious pride of the city, its navy, lying scattered across the rocks of beach after beach on distant shores--smashed, beaten, defeated, then driven by storms onto the rocks to finish what foreign powers had started.

The few, tattered-sail remnants of the once grand navy, with only a hundred men or so surviving from the ten thousands sent forth on a thousand, flag-decked ships all bristling with cannons, crept back into Baton Roo, heading for the Arsenal for repairs, as they were sinking even as they sailed. The Doge saw himself in the song facing a riot of the citizens, who were so enraged at him they had set fire to the palace, driving him up to the roof, as he could not go down and not be cast into the canal and drowned like an unwanted dog or cat.

If that wasn't bad enough, each listener present saw his own shame and perfidy and evil-doing, all done in secret, now exposed to the same withering light that had just shone upon the Doge, making him seem the most pathetic spectacle of a vain, gold-and-glory obsessed man who had overreached himself, who brought nothing but disaster by his plans for enriching and empowering the great city under his charge. His dream of empire cast into the mud, he was finished!

Full of fury (his pomp and splendor put to ridicule by the songster), the Doge stormed away, his aides and guards stumbling over themselves as they tried to catch up. He knew he could not very well end the outrageous concert right then and there, but when he regained his private apartments, he ordered the servants out and sat alone in his chair, wondering how to best deal with this all-revealing, all-too-candid songbird on his hands. As for the nightengale's ominous hints about the royal navy and a coming defeat of his war fleet, that was nonsense! he thought. Nothing the old empires had could equal his navy! He would sweep their fleets away like autumn leaves in a West Wind, strip all their ports, both on the sea coasts and up the rivers, completely bare. Then he would send his soldiers aboard his troop ships ashore, where they would loot and sack and do whatever soldiers are known to do, while others loaded the ships with the spoil to carry back to Baton Roo. His enterprise could not possibly fail! The nightengale was crazy--and also a little dangerous, if such things as he had sung about were believed any anybody. Best to have the boy strangled as soon as possible, with his body thrown into a unused cistern and bricked up so there would be no sign of had happened to him.

But what about the aristocrats, the proud and lofty class that resided high in golden and marble suites in the many-storeyed mansions along the canals and who flitted about in sleek, swift, gilded gondollas from one party to another? Their sophistication and culture reduced to tawdry shreds, these leaders of high society visibly twisted like criminals in a bonfire as they were shown to be nothing but vain vapors, treacherous ones at that.

If the facts were made public, which they were not, Baton Roo was a giant floating cess pool of crime and perversion and lust and violence--all covered with a glittering exterior that fooled even the most cynical. And Isma's chief imans lifted their golden gloved hands and gave it the blessing of God! The holy leaders were themselves the worst satyrs and perverts--though they taught that the people should practice strict moral and attend rigorously to their duties of prayer and tithing and giving their sons and daughters to the religious orders. All this the nightengale faithfully revealed. It was as if the whole city was reflected in a gigantic mirror that showed every flaw, sin, crime, and folly hiding beneath the glittering surface.

The Doge took the song as a personal insult rather than a timely forewarning of impending doom. He issued orders for Pio to be taken quhiet away and disposed of in the way Baton Roo undesirables were--an unwitnessed assassination, then a private burial at sea. Strangled with a bow string, or poison, or the dagger, the exact means were a matter indifferent to the Doge, just as long as the nuisance was dispatched and no trace of him remained in the city.

The Marshall-Prefect of the City, however, privately demurred when he received the Doge's orders. Being closer to the people, he could foresee the effect this disappearance of the people's darling would have. It was not a welcome thing in a time of war, for it would divert the people in a way that could possibly undermine the war effort.

Already over-taxed, the city was ripe for rioting, he knew. The poorest district, with its tall wooden tenements, were just waiting for a candle thrown into a heap of papers or rags. The rats' warren thousands of Baton Roons paid high rents to live in, was a place they would gleefully put to he torch, even if it meant losing their wretched possessions--they hated their oppressors that much and, thus, would not pass up any opportunity to strike back.

No, he decided, he would not risk it. A Doge could always be replaced, but not the city. With no holdings on the mainlands on either side, Baton Roo had no place to flee if they lost their home islands.

The Doge was foolish to risk the safety of the whole city in order to assuage his wounded pride--pride bitten to the quick by a little boy's song!

Charged with the city's safekeeping and policing, he saw no need to sacrifice the city for the Doge's vanity. Quickly, he decided how best to circumvent the Doge's command. He went in person and, after ordering all the servants out, instructed the boy as to what he must do, and then the Marshal rolled him in a carpet. A beggar boy's body, found drowned in a canal, was substituted for Pio, and dressed in his fine robes, and then carried out by retainers past the ducal apartments, with the Doge looking on approvingly through an ivory screen, that shielded him from profane public gaze.

That very night, in the early hours just before dawn when the city's last party goers had been carried to their beds while sunk in drunken sleep, Pio was on his way by a swift boat to an outlying islet with a watchtower the Marshal kept manned for just such delicate operations as this.

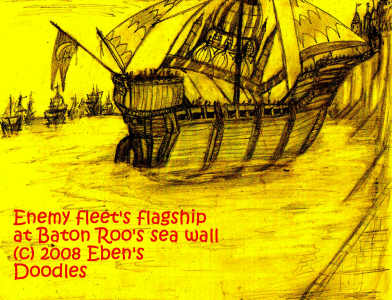

Two weeks passed, and then on the report that a fleet was approaching, the populace gathered festively attired in their most gorgeous clothes on the sea walls by the tens of thousands to watch their victorious fleet returning. But there was no victorious fleet, only a few remnants, their sails torn, holes blasted in their hulls, signs of bloody fighting and even fire, scarring them as they limped, sinking, back into port.

Rumors raced throughout the city. What had happened to the navy? What had done this to the fleet? Was it almost entirely lost? Were more such sorry specimens coming? Or was this all?

More thousands flocked to the sea walls and the sea gates to peer, wives and families looking out anxiously, forgetting to eat and drink, and the weeping increased hour by hour, as despair set in. All was lost--lost! The men weren't coming home! Husbands, fathers, sons, brothers, lovers, friends--ten thousand vanished in the Doge's insane gamble and campaign against the empire of the South.

All these families and wives and children of the slain sailors and soldiers, they were ruined, and the city itself was ruined, for without a navy Baton Roo was utterly defenceless. Anyone could send a small force now of middling warships mounted with a few cannons and seize and plunder and destroy the once great and powerful city, burning it down to the water line after they finished raping the women and sacking all its treasures.

Terrified at their coming fate--for there would be no escape from their many enemies, they knew--the women rushed to the shines and temples of Isma for safety, and there the imans and mullahs prayed day and night, prostrated, for the city's deliverance.

What men there were left, together with the Marshal and the royal guard who now went over to the side of the rebels, joined mobs of angry women and stormed the palace. The Doge, taking his secret staircase below the canal, then crossing to a locked up mansion, intended to escape by night in an ordinary looking sailed boat he had filled with gold and jewels. With his money he could go and bribe even the Kaliph himself to take him in and give him safe haven.

But when he reached the mansion via his secret tunnel, he found the door opening to it locked and barricaded. He was forced back into his palace, which he found in flames. Where was he to go now? He began to run this way and that in the palace as more and more of it erupted in flames. Chased down, he was allowed to flee into one of the towers overlooking the Grand Canal, and when that too caught fire from flaming arrows shot through its windows, the city's populace watched as the Doge's writhing body, in flames, fell into the water and sank like a stone, weighted down as he was by his heavy, gold-threaded robes and the big pockets he had filled with jewels.

But the jubilant crowds did not have much time to rejoice over the fall of the wicked Doge. They now had the Marshal and City Prefect as their leader, but his palace guard could not protect the whole city from attack. With only a couple ships, and the gondollas, left to him to use, what was that against a trained and equipped navy sent by their foes to capture and destroy the city?

If they fought, they lose everything. If they did not fight, the result would be the same. Their enemies would kill the men and rape and enslave the women, and after that burn the city after it had been sacked.

In despair the people stood watch on the towers and the walls, watching for the inevitable warships to appear on the horizon. At least they could give a warning in time for the people to flee as best they could by gondolla, those who could find one for hire, or owned one, that is. The majority of citizens were without even that slim hope of escape, and would remain where they were, to suffer all the enemy would inflict upon them as a defeated nation.

Isma had failed! The mullahs and imans in the splendid shrines and temples no longer offered up prayers, for what use was that now? Kismet had fallen. Their fate was decided and sealed. The eternal scales of justice, which were set even above Isma and the Prophet, had weighed their good and evil deeds, and their evil outweighed their good--or so they reasoned. They were all finished! Death was coming, full-sailed, and banks of oars plying vigorously along the sides of hundreds of incoming warships.

The Empire of Multan and its allies, joined by Baton Roo's rivals on the two mainlands of the Turtle, the were coming to exact full vengeance for the Doge's treacherous attack, that would have succeeded if only someone in the Doge's own war cabinet had not forwarded copies of his plans to Multan's Kaliph.

The people on the walls and high in the towers felt their blood run cold, and their faces turned grey and ashen, as they watched the entire horizon fill with sails and prows. The armada was vast, like nothing the Turtle Islands and Baton Roo, their queen city, had seen before. Nothing could stop such a force from its objective--the utter annihilation of the hated robber city and the plundering of all its wealth.

While the people were weeping and casting their gold and jewels into the canals, and even setting fire to their houses, so as to throw themselves into the flames and perish, rather than suffer the violation of their daughters and wives while they were forced to look on, something unnoticed but strange was happening. A tiny craft was launched from the far-off islet where the little watchtower stood, abandoned, except that the isle had been used at various times for exiled stray cats that were dumped there to rid the city of unwanted pests. They usually starved on the isle, so it was a cruel place for them to be put. Pio found only a few cats still surviving, and he fished every day to supply them with food. When he wasn't fishing, he climbed the tower to gaze out at his city, wondering when he would ever be allowed to return.

No one noticed it until it was right under the city's walls and at the seagate leading to the South. Paddling along in his tiny, improvised tin boat, Pio fought the swirling currents and turned the boat toward the city's seagate. Where had he gotten his boat? Only a canal boy could have done it. He had taken an old, discarded, cracked tin wash tub that had washed up on the isle's beach and patched it with leftover pitch he found in the tower that had been used for the roof's leaks. Covering the bottom with a layer of wood and sand to keep his feet out of the pitch, he had set off. Pio was dressed raggedly and comfortably again as a canal beggar boy, but with no shirt, so he could paddle all the harder. It wasn't something he knew little about. He had made little boats before. He knew how to propel them too, so he quickly made headway back to the city so he could look up his father and give him the loaves of bread and the wedges of cheese he had brought along from the food his guards had left behind.

Pio was recognized by some, however, and then his name spread until thousands were saying it.

While the rescue was going on, other matters were being being arranged that affected the city's destiny directly. The Grand Marshal, now the acting, if not official Doge of the city and principality, sent an uniformed aide to the south seagate, with commands to the guards and their commander. His men had notified him about the events on the wall, including Pio's rescue by a circus performer. Could they be used somehow? Quickly, the Marshal thought of a plan, that might work to stall the enemy just long enough for his secret weapon to be launched and sent out against the enemy.

Men hurried to the gate by the most swift gondolla available. They raced and pushed through the throngs that were massed around Pio and Antonio. Pulled aside, Antonio was informed by the commander of the South Gate, that he was to hold the enemy fleet's attention in any way he could and as long as he could. It meant the city's very survival! Could he do it?

Antonio, with the likes of Pio in his charge, together with the rest of his circus family, including some musicians, was up to the challenge. "Yes, Your Grace, we shall hold them, we know every trick, and they will not do anything to us as long as three days--rest assured!"

Three days? He had entertained crowds in the city's major squares for as much as a day, with multiple acts, but three days? Pio, obviously, was Antonio's trump card, for whenever Antonio's circus acts palled, Pio would be brought out with fanfares of golden trumpets and the dancing of beautiful girls.

With no time to waste, Antonio gave orders to his family members, and they ran to bring the various animals, ropes, costumes, instruments, and other items needed.

While the things were fetched and the stage erected on the wall, Antonio jumped into his simian, long-tailed costume and began cavorting and playing tricks on the parapets, to capture the attention of the admirals and their navies and postpone the initial ultimatum and then the bombardment if the city refused to surrender (and, of course, they would refuse).

With ropes hanging down and secured to the parapets, Antonio could scamper along them, then climb up, then perform all sorts of precarious, hair-raising, amusing capers, with the musicians adding to the din and confusion and interest. He knew the fleet's commanding admiral would be examining the walls right at that moment for weak spots in their defenses, and would be astounded enough to call a halt to the fleet while they tried to fathom what it was they were seeing.

It was just as Antonio had planned. The South Gate's commander watched in amazement as Antonio went through his daring escapades high above the water without a net (the rocks waiting for him below to make a misstep) and the incoming fleet slowed, then stopped in its tracks, evidently stalled by the spectacle.

Antonio continued his antics as long as he could keep the enemy's attention, then the moment the stage was mostly complete, he directed his family to escort Pio to the high stage, and to sing his little heart out. From that high vantage point, his voice would carry a long distance across the water, if the crowds were quiet. The commander, informed by Antonio, immediately moved to command utter quiet, and the crowds, realizing that something unusual was about to happen, hushed. All that could be heard then was the banging of hammers and the roaring of the ironsmiths' fires in the the Arsenal as final touches were put on the Marshal's secret weapon.

Patting Pio's head, Antonio grinned with his monkey's grotesque face, making the boy laugh. "Laugh now, but don't laugh when you sing, my boy! Sing like a nightengale, with its little heart breaking for its thorn-pierced and dying mate!" Antonio cried up to him. "Sing, my little friend, your loveliest songs that will melt the hearts of the very dragons and beasts of the deep! Those are most cruel men out there coming at us with their cannons and scimitars, but they can be conquered by such a divine voice as yours! They not have heard its like. I know you'll do it! Capture their cruel, black hearts and hold them prisoners, just like you did to all of us here! Then purge all the blackness out of them--make them white and innocent as doves, so we can take and wring their necks!"

The enemy fleet had moved, in the meantime, its hundreds and hundreds of ships bristling with cannons and guns and and battalions of armed soldiers and navymen drawing closer in, still without firing. An envoy's boat was being prepared, and manned, to deliver an ultimatum--a mere formality, since the attack was planned and was inevitable.

Even while the envoy was on the way to the blocked gate, Pio began to sing as only he, with a voice heard but once in a century, could.

Mesmerized by Pio, the enemy admiral of the fleet that had Baton Roo at its mercy, the attack was delayed three days, while Pio and also Antonio performed, distracting the enemy so much that the Marshal had time enough to finish his ultimate war machine in time to set his secret master plan in motion.

The coalition's commander in chief, The Lord High Admiral, Enver Mustapha Atta Obaldis Hussain Obama, was impatient to begin the bombardment and the annihilation of the city.

But the inevitability of their utter destruction had worked a serious and profound change in the wicked hearts of the Baton Roons, high and low, whether they lived in a palace and hung out in canal side taverns and brothels and slept off their drunken binges in stinking, pigsty-like tenements overflowing with rats and garbage.

Isma has deserted us! they cried. They had all sent sacrifices and gone in person if possible to the temples, throwing themselves on the mercy of the All Merciful One--but he had not heard their prayers, as the fleet was present in full array on their doorstep, intent on slaughtering them all, or after killing all the men and elderly and the children and the sick, taking the remaining good-looking girls and women off to harems and slave markets or to serve out the rest of their days as the lowest household maids.

The Baton Roons all knew they had been too evil, committed too many wicked deeds, been too sloppy in their religious duties, to be forgiven now. Their strict religion demanded that they pray five times a day, observe the various fasts and pennances, at the scheduled times and in the prescribed ways, or they would be rejected by Isma. They must work their way to heaven. Their entrance to heaven was solely based on their own merit and the tithes they paid to the temples and the fasts and the other religious duties they performed, such as making a lifetime pilgrimage to Multan's shrine of the Prophet and praying five times a day (or paying someone else to do it for them). Isma was the religion of the Compassionate One, the All-Merciful (so their Prophet's God was called), but you had to earn mercy--it was not freely given, it had to be earned by complete, perfect obedience in the ways the holy book of the Prophet and the mullahs interpreting it prescribed. Perfect obedience and submission brought a place in heaven--possibly, that is all they could hope. Even the Prophet, when asked, could not assure his followers that he would make it into heaven, as the All-Merciful was not bound to let any man in and did as he pleased. He too was not immune to being cast into the eternal hellfires of damnation!

No one could shed blood or make any sacrifice that would insure a place in eternal heaven, and escape hell. They could kill thousands of infidels, that could gain some favor, but it didn't insure a place in heaven--just a better chance. They could make a thousand holy pilgrrimages to Holy Multain, be the Kaliph himself with his direct descent from the Prophet, and yet land in hell, tortured by flames and devils. They were doomed if they did everything perfectly, and most certainly doomed if they did not! This was the razor's edge of salvation and damnation, heaven and hell, on which they all were suspended by the most slender threads! No wonder lifelong anxiety gripped their hearts, for by that slender, frayed thread, resting on that terrible, unforgiving razor's edge, their whole religion, their eternal destinies, were balanced, and thus anxiety and constant peril kept the coffers of the temples overflowing with offerings given by Ismanic believers, and the mullahs immensely powerful. The mullahs were so powerful, in fact, they could make even the Doge tremble if they so much as frowned at him when he came with his chests of gold and jewels for the saving of his soul.

Wearing mourners' black sackcloth, fasting, crying out for forgiveness for their sins, the people wept and struggled to get near the wall where Pio was singing. There they heard quite a different tune from the one sung by their grim, condemning mullahs. He did not sing about Isma, he sang of an unknown god of true grace and mercy. He would ordinarily have been decapitated on the spot for blasphemy and desertion of Isma, the only true religion in the world, but here, in the city's moment of greatest peril, the mullahs were powerless to do anything. They had nothing, everyone could see, no power to avert the city's destruction and the bloodbath. Without opposition, Pio sang of what welled up in his heart, unbidden, given him by the Wind of Heaven, a divine Word that came in response to the pathetic cries of a despairing, hopeless people who acknowledged finally what wretched sinners they were.

Yeshua--for it was He of whom Pio sang--always hears such prayers, rare as they are among men. He is always looking for a man who truly seeks God and will always reveal His saving Word to him. So now Yeshua came down, in the Word, through the songs' lyrics, sung by Pio, a blind beggar's and a canal prostitute's castaway son.

Unknown to the city, in a formerly secret chamber, the marshal set men working at a giant turnscrew.

The Marshal had decided that ten warships they might have launched were far too few to matter and would produce only negligible resistance. They would be immediately cut to pieces after the vast enemy fleet encircled them like a cat playing with a mouse. But the very sight of the monster warship he envisoned launching from the Arsenal's secret sally port did not fail his vision of it, for the warship, incongruously called The Tulip, now sent paralyzing terror into the hearts of all the navymen in the enemy fleet. They were all the more unhinged because they could not know if there was not another, and yet another, waiting in the city's Arsenal, standing ready to call forth. They would no doubt assume there were more--and would not stop to see if the city had only this one Tulip in its vase. The only choices open to them--stay where they were and be destroyed, or flee for their lives. Which would it be? They were not given much time to think it over.

Its cannons blazing, the ship-slaying Tulip moved against the Admiral's flagship, riddling it with holes like a cheese, blowing up the fore and aft officers cabins, killing the Admiral himself in his stateroom. The next salvo made a direct hit in the munitions and powder kegs of the magazine, and the entire vessel exploded in a tremendous fireball, with debris and bodies blown high into the sky.

Baton Roo, undeserving though she was, was spared! But not only the city, the people were saved! They had become new in their hearts--all the blackness wrung out of their hearts and made white and innocent as doves. They had believed in the Yeshua the Savior and Lord that Pio had unwittingly sung about from his heart, after he was blown upon by the divine Wind and Word of Heaven.