“Now say your prayers, darling, and go right to sleep and you can play with Missy Tookins or Teddy Bear in the morning, but let them sleep now, for they are very tired, poor dears.”

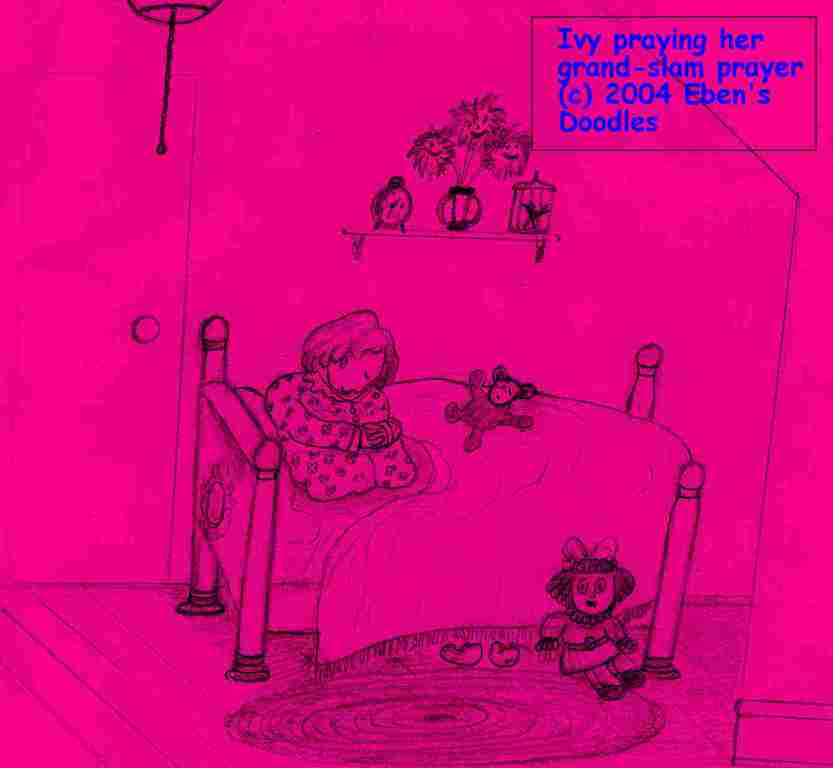

Her four year old gazed up into her mother’s eyes with an obedient expression, for she was quite a good girl without needing much effort to make her be. Having learned her prayer from her mother’s somewhat unenthusiastic recitation of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, Children’s Revised Supplement Edition in Big Print, little Ivy could say it herself without any prompting.

“Now I lay me,” she announced very solemnly and High Church, “down to sleep,” she continued in a sing-song manner. “--I pray the Lord...my soul to keep....If I should fly--”

The little girl drew her breath, then began again. “If I should fly--”

Imagining she was in some long-drawn-out church service with a droning vicar holding forth on incomprehensible niceties of theology, her mother's eyes were glazed by this time, but she caught the gaffe and broke in with “--DIE, dear heart, not fly! 'If I should die before I wake, I pray the Lord my soul to take!' There! Say ‘Amen,’ and close your eyes, my darling, or little Missy Tookins will have red, swollen eyes tomorrow!”

But Ivy wasn’t finished, and ignored her mother’s contribution. Her eyes were open and she continued doggedly, “--if I should die--”

“That’s right, dear, but I already prayed God for you. Now please go to sleep like a good little girl.”

Gently but firmly laying her daughter's head down with one hand, she pulled up the covers to her neck. Kissing her own index finger and giving Ivy a buss on her petal-pink, down-soft cheek, she then pulled the overhead light cord, dimming the light, and crept out. For some reason, she paused just before she closed the door completely, listening to make sure, as any sensible, book-trained mother would.

“What?” Mrs. Wintergreen cried behind the door, almost trembling on her feet in surprise and alarm. “How on earth did she learn that, all those new words?” Her mind was churning--“lair”? “bomb”? “Shickelgruber”?

Beside herself, she turned went back in the bedroom with rebuke in her voice. “Daddy has been telling you things he shouldn’t! Mummy doesn’t like that! Now you forget them, and don’t say them ever again, do you hear? Ivy?”

Confused, but thinking her mother had called her a bad girl, Ivy began crying. It took the mother several minutes to calm her, and then after a kiss and hug she went to the girl’s father, determined to have it out with him immediately.

Waiting for her in the downstairs livingroom, he looked startled when she got after him for saying things no little girl ought to hear.

“Why, for the life of me I don’t know what you mean!” he protested. “What things did I supposedly say to her?”

Mrs. Wintergreen’s eyes flashed, for she was, she thought, defending her daughter’s innocence against the horrid, dangerous world outside her door, the world in which the likes of Shickelgruber, Mussolini, Franco, Djugashvilli, and other such unmannerly monsters prowled about. “Now don’t you try to deny it! How could you be so cruel and thoughtless, Osbert! She has such tender ears, and now you’ve--you’ve--”

Since she looked like she were working herself up into a fit of tears, Mr. Wintergreen also became upset, only he controlled his emotions better, and merely locked his hand on his pipe and squeezed it mercilessly as he tried to get a grip on the sheer misunderstanding.

“Please try to explain, dear, what is going on here. You went up to bed, to tuck her in after her little prayertime, and then you fly back down here, furious about something I supposedly told her. Now what do you say it was? I can’t very well tell what it was myself, unless I said it, and you can see very well I don’t know what it is, or I wouldn’t be asking, would I?

Somehow the logic of his protest seemed reasonable enough, and his offended tone was just right to make her feel a bit guilty over the excess of feeling she had put into her mother’s natural outrage. She softened a degree, and put a handkerchief to her eyes, then began again.

“I just meant, Osbert, that you should try to be more careful. Casual remarks about bombs and rockets and that terrible German person over there--”

Now Mr. Wintergreen’s patience was strained beyond control, now that his wife was showing reasonable restraint. “But I never mentioned a bomb once to her!” he cried. “Nor have I ever dropped one word about rockets, and if you think I’d be insenitive enough as a parent to mention Shickel--”

Mrs. Wintergreen, satisfied with her own compromise, but not willing to let him entirely off the hook without real proof, stiffened. “Well, you certainly talk about such things to your fellow workers at the office, don’t you? Quite possibly, you received a call, and she overheard you discussing bombs and rockets and such dreadful things. You know very well Dr. Hyppia-Treves book which we both read before deciding to have her, warns about this very thing, for it could make an impression on her young mind it will take years to work out of her. I really think that’s what happened. Then you didn’t see that you were filling her ears, and so I suppose I must forgive you, since it wasn’t intentional. But, dear, you must be more circumspect in the future!”

Mr. Wintergreen looked as if he couldn’t believe his ears. He paced back and forth, throwing up his hands for emphasis. “But what you just said is utterly preposterous! Preposterous! There was no such conversation on the telephone. I can assure you, I haven’t received any call here that caused me to talk about the things you accuse me of! Such subjects simply don’t come up, or I’d remember!”

The mother laughed. “My daughter repeated your every word, so she had to have gotten it from you, since I never said anything of the kind to her! Talk your way around that, Osbert darling!”

Mr. Wintergreen was now outraged. His face was flaming, and he looked as if he might throw his pipe into the grate and stalk from the room, but he was made of stronger stuff and stood his ground. “I tell you, once and for all, she got nothing of the sort from my lips. It had to have come from another source, entirely outside the family circle! And, furthermore--”

The argument, for want of more proof either pro or con, continued until the parties were exhausting the English language, and then the radio happened to be mentioned. Without thinking, Mr. Wintergreen flicked it on just to clear the air a bit.

The volume turned full up, a news broadcast blasted into the room. “The latest report of aerial bombing campaign by enemy rockets and planes now includes a most singular event occurring at 6:30 this evening. Intercepted by our coastal radar, the incident has caught the attention of the foreign secretary, and the chief commanders. A bomb-carrying rocket, launched from occupied France, was traveling at high speed over the Channel when within minutes it turned suddenly round and flew rapidly back toward the launch site, which it overflew, continuing until it violently struck ground at a point identified as Soissons, near the Margival river, in Northeast France--a location that is said to be the site of a bombproof field headquarters for Chancellor Shickelgruber known as 'Wolf's Lair.' The blast was extensive, but we cannot speculate on any effect on--”

Stunned, the parents let the broadcast continue, but there was little more of substance, and Mr. Wintergreen flicked it off when it turned to a facial soap endorsement attended with a full big band accompaniment.

They looked at each other, and there were no words that could have described what they were thinking and feeling. Mrs. Wintergreen went and sat down on the nearest chair, and Mr. Wintergreen tottered to his.

The next day, while Mr. Wintergreen was at work, the mother went to alter a hat at the millinery shop (her patriotic duty was to alter old fashions so that that material could be saved for balloons and parachutes), and she couldn’t help relate the incident that had troubled her whole existence since 6:30 the following evening. Had she slept one hour? She had found her face creased in several new places, she had been so restless, tossing and turning all night.

“But what time was the broadcast, Madam?” the girl wanted to know after Mrs. Wintergreen had given, she thought, all the particulars.

“It was maybe 6:45, for I spent more time than ordinarily with my daughter due to the fuss she made at bedtime.”

The girl shook her head. “There’s some mistake, I’m sure. I was listening at that time, but the channel was dead, since we had been expecting an emergency broadcast or something after the bombing struck so heavily on southeast London. But the radio didn’t come back on until 9:30, and then I had to pop off to bed without getting to hear any band music, which was why I had it on in the first place. I always listen to good American-style band music while I relax a bit, and read some in a book, before I go to bed.”

“Really!” Mrs. Wintergreen replied. “I am telling you exactly what occurred, and there couldn’t be any such mistake! My husband and I both heard the broadcast, so you must not have turned your set on, or the volume was too low or something for you to hear.”

The girl wasn’t having this, and she shook her head. “It was on, all right, Madam. And I always have the volume on high, for I don’t like to hear the coal and troop trains going by so close. So there was a mistake, on your part, Madam. I could have heard the broadcast if there had been one.”

Now, corrected by all things a shopgirl, Mrs. Wintergreen couldn’t believe her own ears. Her mouth fell open, and she was at a loss for words for a moment. Her hand spoke for her. She seized her unaltered hat, forgot all about her patriotic duty, swung around, and stomped out of the shop and slammed the door.

She reached her home by car, and was still furious. The door banged behind her, and then it was some time before she calmed down sufficiently to think of what she needed to do for Ivy and her husband for their dinner.

She was late in preparation when Mr. Wintergreen, carrying a Portsmouth paper, his pipe in his mouth, came in the door. “Hi, luv!” he called out cheerily. “How’s--?” he craned his neck toward the nursery.

Mrs. Wintergreen, having not checked in at Ivy, being so obsessed with the rude shop-girl’s remarks, now dropped everything and ran upstairs. A few minutes later she came down, looking embarrassed.

“She’s quite fine. I left her with her dolls to do a bit of napping, and she was playing quietly when I came in. I need to get dinner ready now--”

She turned briskly to her wartime gravy and potatoes, but forgot an ingredient and when she tasted the gravy she realized she had made a dreadful mistake. It was enough to make her stop everything and burst into tears.

Mr. Wintergreen, his nerves jolted to sensitivity by the terrific flap they had just had the evening before, was now confounded and dismayed. “Now what is it?” he cried. “I thought everything was settled. Little Ivy had a bad dream, prayed about it, and it turned out to be something that really happened, according to the BBC. So she had a premonition, or some such thing. That is all it was. Nothing for us to be so upset about! So really, dear, please get hold of yourself!”

The mother sank down on a chair, her face in her hands. “But you don’t know what the hat girl said to me! I was never more insulted. She said we couldn’t have heard the broadcast, since there wasn’t one after 6:30! Can you imagine such cheek! Telling me that to my face, that I am either a fool or a liar?”

Mr. Wintergreen, feeling but not particularly seeing light at the end of the tunnel, touched her quivering shoulders, then raised her up. “Darling, we’ve both gotten upset over a small thing. Don’t take remarks like that to heart. I heard it too, remember? So we know she has it wrong.”

Mrs. Wintergreen brightened. “You think so, Osbert? She was so sure of herself, that girl. I was made to feel like such a fool. With the war bearing so hard on us lately, restricting even what a woman likes to wear, it was awfully hard to take!”

Then, after a bit of making up for the last evening and the troubled night, the Wintergreens resumed with dinner, with the sweetened, not salted gravy, potatoes, vegetables, and a half-roasted, half-charred lamb course.

Mr. Wintergreen decided he couldn’t finish his, and kicking himself for letting the cook go for the sake of wartime economy, got up early from the table, went to his chair, took out his paper and pipe, and the radio was turned on by his wife. Symphonic music from the BBC orchestra filled the room, and things seemed about to resume their normal look. But the music was abruptly cut by an announcement.

“For our radio audience turning in at this time, the administrators and staff wish to express our regrets to all concerning the disruption of several hours of our regular news broadcasting due to severe bombardment striking near our facility, which severed electric lines and--”

Both Wintergreens hung on the man’s words, waiting for the time of the disruption, and when it was given, the color drained from their faces.

“Then that horrid little milliner was right! There really was no broadcast!” Mrs. Wintergreen quailed.

Mr. Wintergreen’s pipe fell out of his hand and he didn’t notice. “Let’s NOT jump to conclusions like that. We heard it! Yes, we heard every word of it!”

“Yes, we did, but no one else did.”

The room seemed to grow intensely quiet.

Then: “What do you mean by that?” Mr. Wintergreen said.

“I mean we heard it, but it went no further than this room, that’s all.”

Mr. Wintergreen stormed out of his chair, striding up and down the rug. “That’s preposterous! Utterly preposterous!”

“Well, explain it some other way then!”

The challenge, flung at him, stopped him dead in his tracks. “There is no rational explanation for it!”

His wife laughed. “Just like a man to say something like that! But there has got to be an explanation.”

“No, no!” Mr. Wintergreen exploded. He continued his carpet crossings. “Little Ivy had a mere presentiment, and we happened to hear a broadcast that no one else heard--that’s strange, to be sure, but I challenge anybody to come up with a reasonable cause for it! Anybody!”

Mrs. Wintergreen faced him with a tight, little smile. “Anybody? Well, I will furnish you the challenge you seek, sir!”

“How so? I’ve heard all you’ve got to say on the subject. You must give something new, and it must lend itself to proof.”

Mrs. Wintergreen then stood, and she began her pacing. “I know my daughter, and she didn’t come up with such words and sentiments by herself. They’re not like her in the least. But she got them from somewhere, from someone--though just how I haven’t any idea. Unless--”

“Unless?”

“Well, they could be divine in origin, which would also explain the solitary broadcast.”

Now Mr. Wintergreen, who unlike his spouse hadn't been churched in the least, was genuinely shocked by his wife’s mystical bent, which hitherto he had not suspected in the least. “Divine in origin? That is the most absurd thing I’ve heard yet.”

“So you say!” she returned him hotly. “But it must be the cause. There can be no other, unless we are both mad, imagining things that never happened. But since we both know they happened, and poor Ivy was not herself capable of manufacturing them, then God was the Agency that produced both her presentiment and the confirming broadcast.”

Her logical case for religion, which he hadn’t expected, quite took the wind our of Mr. Wintergreen’s secular sails. He looked wan and slumped into his chair.

But, having won her case apparently, by the looks of Mr. Wintergreen’s abrupt retiring from the argument, Mrs. Wintergreen felt her own deficiency most keenly, and jettisoned her entire case. After all, how could she be so right, and her husband so wrong? He had never been so wrong before, she considered. The whole drift of society, she knew, was with her husband and his way of looking at things. Until now, she hadn't an objection. Why should she change vessels in mid-stream? She might slip into the water and ruin her dress!

“There, there, dear,” she said, comforting him as he looked as if he might be needing a drink at the pub to restore his world. “We’ve both suffered a nasty jolt or two, but it’s not the end, and things will turn back to normal soon, and--”

But Mr. Wintergreen wasn’t receiving wifely comfort at the moment. He looked into her eyes with the most earnest sobriety. “But you really think she is a prognosticative soul, do you not? That she could foretell the rocket-bomb’s coming that--”

He went on a bit more, then his words failed. “Oh, Osbert!” she cried out, wringing her hands. “You really don’t think--surely--surely not--!”

Some things being unthinkable, the more the hapless Wintergreens stewed about the greatest event in their lives, the more unthinkable it became.

The object of the parents’ misery? Little Ivy, dragging Teddy Bear by the ears, came down the stairs, chanting the prayer of the former evening. It ruined a second evening, on hearing it repeated.

Hushing her as soon as she could, the mother bundled her off to bed. Later, she returned to Mr. Wintergreen, who was waiting for her in bed.

Not another word on the subject was said. What had become unthinkable had now turned unspeakable--that a little girl’s prayer could turn a thundering rocket-bomb around in mid-air, sending it hurtling against its fiendish mastermind far off in northeast France...the Wintergreens had now decided was best kept in the family closet--the same that would have been blown sky-high sometime around 7:15 p.m. if things had gone as planned.

As for the evil genius behind the incident, he fled his underground command headquarters, Wolf's Lair. He fled eastward and never again personally conducted the war on the Western Front from so close a vantage point in the west.

The unexpected, tremendous shaking of his headquarters, his thinking at first it was an earthquake, only to find out it was caused by “friendly fire,” rattled his nerves and his confidence badly at the time. To restore his calm, he knew heads would have to roll--but which heads? In place of those British souls that the malfunctioning Portsmouth rocket bomb had spared, he decided there would be a million Russian Slavs that would join the Mongol-like skull heaps of the Jews.

Revenge, how sweet it was! It made him feel better even before the dust had settled around him at Soissons, and his frantic aides returned to him and brushed off his uniform and moustasche. Yes, he felt better, but still he wasted no time in exiting Soissons, and never even glanced back from his departing limoisine at the huge blast hole that lay ten yards from the entrance of the headquarterts, a hole that had engulfed an entire barracks of the SS.