Broadcast by horns and word of mouth, the alarm had gone out to many villages in the mountain valleys. They had come and were taking able-bodied men this time, leaving the old people, and women and children to starve and end up gnawed by wolves. They came so swiftly that there was no time to escape. Village after village was stripped of able-bodied men. With no men to protect the villages, other villages sent bands of men and they fell upon the defenseless, carrying them off with their flocks and goods. Some of these were not so fortunate, and the harvesters spotted them, and they too were captured, while not long after their own home villages, left undefended, were seized as prey by other villages.

Well, now he knew where to go and find his wife and children. Maybe, if he was cunning enough, he could also steal some of their small cattle for the trouble they had given him. He might have to kill a shepherd or two, but he had his good arrows, and was a good shot. He would hide behind trees, following their herds, until he spotted his opportunity to single out one herd and one shepherd without the others finding out and chasing him. After that he would go back and, dressed as a lowlander and speaking as one, seek to enter the village and get his wife and children out. He would let them know where he would be waiting in the night, and then it was up to them to run to that spot without awakening the others. It could be done if all went well, and the village dogs were thrown some meat or carcass to chew on that would distract them. Hares would do nicely for that.

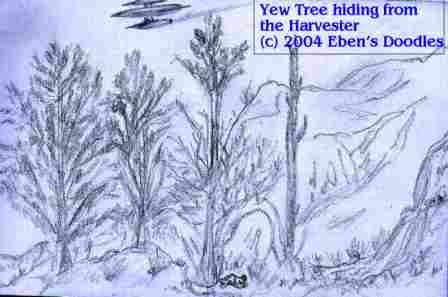

The truth came to him: the Harvesters had come! He had heard of them coming in the long-time ago of the unclothed Ancients, but it was now his village’s turn. Once they had taken blood, leaving the dry husks of bodies behind—but that changed, and they were taking bodies now. There had been no escape back then for the people taken, he had been told by the old tales. But Yew Tree was not as compliant as the others had been. He possessed a streak of independence that made him always seek an alternative way of doing things, even if it wasn’t always the best way. He was stubborn in doing things his way if at all possible. Now in a crisis this flaw or strength came to his rescue. He wrenched his body free of the paralyzing ray that turned a man’s strength to melted butter, and staggered away, gaining speed as he pushed himself to flee against his sluggish body’s will to remain and be captured like a fluttering, little bird for the soup pot.

Yew Tree sank down amidst the pines and maples.

It was late in the last grazing season, he needed to go back down, or he would be caught in the bitterly cold storms above the tree line where only the snow demons lived.

He started walking, choosing an abandoned goat path that he knew about, but which the village did not use, since it was too narrow and rocky. He was glad he did, for the Harvester passed over once again, and he just had time to dive out of sight under some boughs of the nearest tree.

Now what would he do? He couldn’t go farther and not expect to be taken in the open country, could he? If his mountain village had been such easy pickings, the villages in the plain were like nests of eggs laid out in the open meadow.

There was only one way out. It was the most risky of all, but he would rather die than be taken like the others. He had never been a sheep or a goat, to be made to go here or there by others. No, he would die as he had lived, his spirit like the great black-winged one who flew as king over the mountains and their forests and valleys, his gleaming gold eye missing nothing, no matter how far.

As soon as he saw the flying Harvester had left the area, he started climbing back up the mountain, heading to the river country on the far side that he had once seen in his youth, a time he had ranged far and wide with his two oldest brothers before they had fallen into a crevasse when a snow bridge collapsed, leaving him as the eldest.

When he dared, he lit a small fire of alder and willow, letting it burn down. Absorbed in his troubles and the all-consuming problem of preserving his life against terrible odds, his eyes were blind, whenever they turned upward, to the glorious, flaming beauty of the maples, all torches of red and yellow and gold. Clothed in his straw cape, his furry hat tied tightly to his head, his cord and straw stuffed shoes on his feet, and his leather coat and grass-stuffed leggings and loin cloth making him seem a larger man than he was, Yew Tree must have looked like he was enjoying the solitary place when he only wanted to get clear of it. With sticks, he took the living coals when they were ready, wrapped them in the last green maple leaves he could fine, and put the coals in a sack, which would keep them until he needed a fire again. As long as the coals remained alive, life would burn in him too, he knew. Without any chance to make a fire, he would freeze in the mountains like the dead birds he found on the ice, caught in a storm without shelter.

To pass the time he mended his garments with long grass stems, the best he could do without his wife’s able fingers, the best in the village or in any villages round about. No one else could sew leather so closely and snugly as she! What a loss for her to be taken! Could he ever find another woman so good, so utterly the opposite from his fat, useless first wife, who burnt his stew and wasn’t working whenever he was away and he caught with another man when he returned unexpectedly? He wasn’t even sure the children she birthed were his! He was relieved when she slipped off a rock and drowned when out with the women washing the hides one day. His second wife made up for his former misery. Would he ever get her back? He had to try! He knew there was no other as good. She had been named Lime Wood when he chose her, but having cut Lime trees down, he saw at a glance that this was one he would never cut down--so he renamed her Lime Flower.

But first there was saving himself. He would follow the way across the mountains that he had taken when he was so young and fearless as to brave the hostile, fickle forces that could change the weather from sunny and clear to an ice storm before he took his body’s length in steps. He would have to hurry or be caught in bad weather. If he was forced to stop, who knew when the weather would clear? It might last all winter.

A beam of light fixed the spot, and the harvester lowered within a whirlwind of snow, ice, with ear-deafening noise from the rotor only those inside could hear, but the wind was too strong, and and the harvester was forced to leave, to try again for later landing.

Plunged back into darkness and falling snow, the body of Yew Tree was saved for the time being.

But the weather reversed, warming again, and ice water flowed out from around him, and he was again uncovered by the snow. His head was entirely exposed, and his upper back, and right arm. His unfinished yew bow also stuck half-way out of the ice. His ember-sack was still lying clutched in his left hand, the ember long-dead, of course, in its insulation of green-plucked leaves.

Utterly destroying the peace and silence of the place, the harvester returned with its smiling, laughing, talkative reapers, and this time the weather permitted a landing. It was mid-September, and the window for removing the “Glacier Man” was closing rapidly, they knew. Reapers in rubbery-soled shoes and wrinkled suits of many colors with pockets inserted at odd places moved quickly from the craft with equipment, and began to examine and remove the body at the same time. They wrangled about the details, and who had precedence to perform what task. After some argument, the reapers with most claim to senior position and authority set to work.

But the solid block of ice in which the Glacier Man’s body was trapped refused to give him up, and now the wind was so strong the reapers and the helmsman grew afraid they would not make it off for the night. They had tents, but a bad storm could maroon them for days. They might be able to walk out, but it was a day’s walk in good conditions, and could they expect good weather to do it?

A decision was made to leave, and the reluctant reapers packed up and hurried to the harvester. Someone thought to throw a plastic tarp over the naked Glacier Man, and weight it down with clunks of ice and rock. Small animals had been gnawing on him already, and his head looked like a bird had been pecking it in one place, though another reaper thought it might have been a mortal wound inflicted by an enemy.

The storm lasted three days, then warming set in, enough so the reapers returned. By this time the news had drawn world-wide interest. An incredibly-preserved Bronze Age man had been discovered in the Alps! He was thought to be thousands of years old, perfectly, or almost perfectly, preserved by immersion in the ice. It was electrifying news, and the whole international community of professional body reapers was just as much caught up in it as the mass public.

As Lime Flower trudged along with her children and her clothing and loom strapped to her back, she glanced back at the receding mountains from time to time. She knew she would see them again--or die!

She glanced too at her captors, the craven men and boys who had come to attack a defenceless village---who, if their men had been present, would never have dared show their faces! She spat, trying to control her fury. What miserable dogs they were--not like her hardy mountain people! They could kill weak old ones and nursing infants, but they could never stand up to the likes of her Yew Tree.

Her single tear escaped her eye. Yew Tree! Unless he were taken by the Harvester from the sky, he would not rest, she knew, until he brought her and the children back.

Her turn would come, she knew. She wondered if she would fight and kill one or maybe two of them first. She knew she could. She would wait for the right moment then jab her needle, clenched in her palm, into the throat of her attacker, and that would send the blood pouring like a fountain, and he would be dead! Nothing could help him then.

But remembered the children. They would be set upon, in revenge,and probably all killed. They would throw her and her children’s bodies together and leave them for the scavenging dogs that followed them behind. Even the three that were not hers--the ones birthed to the stupid woman who drowned herself washing clothes--she cared for them. They had hated that mother, who let her boyfriends beat and molest them as they pleased when Yew Tree was away. Free of her and her lovers, they were careful to do as she told them, and she was pleased with them. It was not their fault they had such a worthless mother--and their father was a fine man and good provider, that everyone knew.

If he was one not to talk, or did things differently from everyone else--what was that to her? He never beat her. They got along very well. He was hard in his spirit toward others, but soft in his heart toward her. Nothing said against himby others seemed to penetrate, he rebuffed it all with arrow-sharp, scornful replies that no one could counter. How many younger, stronger, boastful men he had outlasted who had sought to rival or overcome him! He was Yew Tree! Before him they eventually became all bending willows and low growing junipers he trod upon. Yew Tree had surpassed them all as a man!

She spat again with all her might, unable to hold it back. One of the captors, a greasy-beared, thin man who walked bent over and coughed from the pit of his sunken chest--glanced at her. He said something to the others. They too looked her way.

Afterwards, she considered something as she struggled to keep up, the pains in her thighs very hard to bear, but not half as bad as the sword-pain of shame in her heart. She considered that Yew Tree better not wait too long, or she would flee with the children on her own. She would wait just long enough for the two youngest to move more quickly than they could now at their age. But she would flee back to the mountains, her own country. She would permit nothing to stop her.

Somehow she had not used her only weapon--remembering her children’s lives.

The hours stretched on, and then they camped for the night. But the fires were scarcely lit when their captors began looking over the women again.

As her captors began to move toward her, smiling and joking to each other, she did something she never thought she would--she threw her needle away with a flick of her hand. Let her skill rot and not benefit these dogs! she thought as she steeled her heart.

Another day’s journey, they reached the village accursed to the captives, their own home place. Men and boys even more wretched than the ones that had raided Yew Tree’s village rushed out to look and gape at the spoils of war. Several skinny-legged, goat-bearded men grabbed the arms of Lime Tree, and her heart sank to its lowest ebb. Another such time and she knew she would tear asunder--die like other women had died along the long route, their blood draining all away down their legs. Now it was going to happen to her!

“Yew Tree!” she prayed silently. “Yew Tree!

It was all she knew, but then a voice spoke to her spirit--

By now the wretched Crooked Willow villagers were pushing and dragging her, to make her lie down for them.

Her strength gone, Lime Flower collapsed on the ground, no longer resisting. Then Someone spoke to her.

The raping gang paused, surprised and bewildered, then they gathered their wits and courage and again attacked, each one seeking first place on the captive spread on the ground.

The next moments bewildered everyone. Arrows flew right and left, from all sides. Bodies fell everywhere, then screams of the dying and wounded blended with war shouts of mighty men. Another, much stronger village was attacking, it seemed to Lime Flower, and she lay where she fell, with her children somewhere out of sight of her.

A short time later, the raiders returned after chasing the last Crooked Willow survivors and killing them, and they stood round looking over the spoils of their success.

A strange thing happened. They paid utterly no attention to Lime Flower and her children, nor to any of her fellow villagers who crouched huddled in a thatch-and-wattle pig pen. But they took anything of possible worth away from the village, loaded it on carts, and then without a backward glance left as quickly as they had arrived.

Lime Flower stood with her children and people, mouth open, watching them go.

Was she free? Were they free? She stumbled about and turned to the others from her village, yet they were utterly bewildered. No one had taken the slightest regard of them either, and they could not understand it.

Finally, Lime Flower’s sense returned. “We are free--rescued by the God of all the Earth, the Great Tree of Healing, He Who is the Beginning and the End of all life! He spoke to me, and told me to pray to Him and then we would be spared, our lives rescued from the mouth of the mighty wolf! And it has been done as He said! He has rescued us by His mighty Hand!”

Then she rose and turned to the survivors. “We can go! So, don’t stand there with your mouths open. God has saved us! Let us go home!”

She grabbed her belongings, and then led her children, even pushing those of her people who were too slow, and they hurried away toward the mountains as fast as human legs could go.