Continuing his journey within the malevolent, evil eye of the Carbuncle's spirit-form, the great Vampire, Ero has no idea what he was going to encounter next, of course. There is no explanation from pop-ups. Yet he isn't particularly worried. This photo-file seems to have landed him a a nicely verdant country, quite unlike most stretches of the more arrid, coral and calciferous White Continent of Atlantis, he finds. It is most pleasant to the eye. He likes the look of its gentle, rolling hills and winding rivers and streams with their thick forests of oak, framed by a line of low cloudy mountains on the horizon. What kind of country was it? Would he find it inhabited? What era was it? Where they civilized? Or barbaric and backward in culture? He knew he would soon find out. He wondered how Damon was faring, but that was somebody else's concern now--somebody who looked surprisingly like himself, he recalled from the brief look he had of him before he was whisked away to other worlds. He had helped Damon all he could (even going beyond the perimeters that Wally had set), but whether that would bring Damon to his destiny, that was something he could not know. Just the same, he hoped it would be a good journey for the young gentleman with the camera--that the best was yet to be.

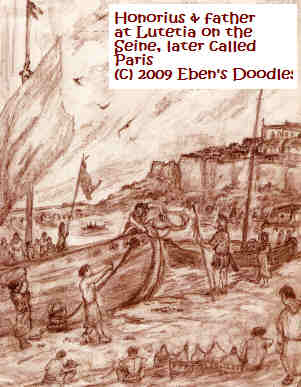

Finally, the mast-bot began to move again without his direction, following to figures in the morning travelling on horseback. They looked to be a man and boy, and then the popup informed him he was correct, he was observing Honorius (the boy) and his father as they were beginning their trip to Roma. Honorius's father had business dealings to take care of primarily, but he took his son along this time, who was now of sufficient age and understanding to learn a great deal from the sights, both along the way and in the Roma. It would be a good education for him, better than any book the boy had, the father thought.

It was a long trip, indeed, once they left Roman-civilized Britannica and sailed across to Roman Gaul. But the same Roman roads that crisscrossed Britannica led straight across the immensity of Gaul to Italia and Roma, and there were numerous inns along the way, strung out between cities, where they could stop at night and take a meal and bath and then rise refreshed the next morning for the day's journey. He even had a fine intinerarium of the Western Roman Empire (purchased at a bookship at the exit of Vicus Tuscus on the Forum behind the Temple of Castor), he could consult any time along the way, with the storehouses, cisterns, inns, halting stations, cities, pretoriums, and some of the major sights marked with easy to read notes and symbols.

The main obstacle would be the great mountains of the Alps, which even Roman engineers had not been able to conquer completely, but once they made it through by the high, narrow passes into northern Italia, it would be a nice, quick run down the straight roads directly to Roma.

Honorious listened carefully, taking in her words, though he did not exactly know what she meant by his father teaching him adult things. What could they be?

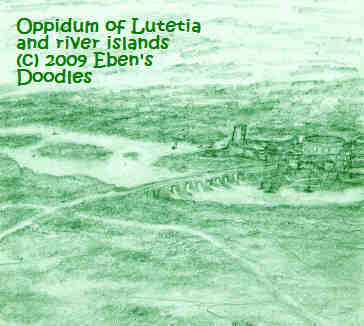

At Gesoricum, however, after consulting with various authorities, Rufus Quartus decided not to venture his son on the now unpatrolled roads but to put the horses on board a ship going to Lutetia instead. This would rest their mounts considerably and also provide more safety, as they were less likely to be accosted by brigands on the road when travelling by water, what with Roman warships still patrolling its whole navigable length.

A vessel, a merchant of sundries which took some passengers and livestock too, was soon found at Gesoricum that was on its way to Lutetia, which was a busy port dealing with the north-south trade and provided the entrepot for a great deal of river traffic. They boarded and their horses were quartered in the hold and given straw to bed on, with barley to eat, while they were given a cabin to share with the captain.

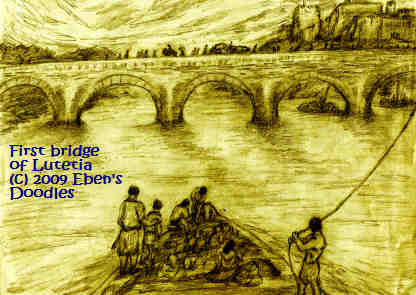

Good sailing weather brought them to the oppidum of Lutetia and the first of two bridges over the river.

It went: "The high gods smile on a sober and decent man, but love a drunkard in his cups far better."

Rufus Quartus, not so easy in his tastes and worldly in his views as the captain, was not so pleased. "Is this such a wicked place as you describe? I hesitate to take my son there, even as we approach it!"

The captain shrugged. "Well, sir, it is plenty rank and rotten as these river towns go, but not so bad in some parts, you'll see. It has many temples to the gods, and they carry on as they always have done there, with the prostitutes, both male and female, adult and child, that can be had there for a denarius, but Christians have their assemblies too in various places. After the persecutions, they were free to take the temples as their houses if they wish, but some prefer the simple houses they live in for meetings still and leave the temples to fall to ruins."

Rufus was interested, as it was near to the Sabbath. "I should like to attend one of those meetings, if I might. Would you know the location of one, where I can find some brethren, for you must know, we are Christians."

The captain nodded. "It takes all kinds to make a fine world such as this, sir! I divined you were one of the Christians, by your manner of acting and your speaking too. I would be happy to tell you what you need to know."

So by the good offices of this captain, they were soon following his instructions and made their way to the church that met in the lower chamber of a ruined temple for the worship of Augustus Caesar, which had burned but was not rebuilt.

"Sister Constantia is well-known to most of us assembled here today. We welcome her in the name of the Lord! We are always blessed whenever she can leave her aged mother in a sister's care and come to share with us what the Lord has granted her so richly of the Spirit. She always comes with a good word for us we should closely heed and obey, as she is a true prophetess, affirmed by the scriptures and by the testimony of witnesses."

The gray bearded elder paused and looked over the people. "But this is somewhat different in its message, for it entails the future and even the far future of this very place and city. It is speaks of a people to come in this city, and what will befall them through the ages, though there is one terrible prince of the Goths coming to invest our city, who will be here in but a few years time. Could you bear with such a grand vision, for that is what it is, and then soberly consider, with fear and trembling, how it can help you walk a straighter way in your own life and time? We must not think it engages only those who will come in the dim future, and so think their troubles need not concern us now, but take it to heart all the more, since we abide here at the beginning of all these woes you shall soon hear about. If only we change our hearts and lives now, and follow the Lord in true obedience, repenting of our wickedness that lurks deep in human hearts, then perchance the city will suffer fewer of the terrible things our sister has been shown by the Spirit of God. But I say too much, as your faces are falling already! It is a truly good word from the Lord, of exhortation and warning that, given to us now, is meant to spare us, not judge and condemn us. Pay close heed and you will be blessed, my children!"

The elder seated himself, and then the prophetess began.

First, she closed her eyes and stood for a time, as if she were seeing other times and an another world. Slowly, without opening her eyes, she spoke almost in a whisper, so that people leaned forward to hear her.

He heard her say the name of the Gothic robber-prince, Alaric, who will be called the Scourge of God. He would come from the east with his hordes and beseige our city, sacking and burning the built up parts on the left bank of the river, but the Lord would afflict Alaric's hosts with plague and runnning of the bowels and he would not take the citadel of the opppidum on the island and would depart--and so they would be spared, because there remained still some righteous people in Lutetia in the church who would pray and fast for their city's deliverance, and the Lord would hear these few. Yet future times would not be so fortunate. The city would be overflowing with screamingly wicked people one day. Spirits of the Adversary, the Devil, all evil, arose from the rank, unredeemed pagan hearts of the tribes and Romans before Christ, and would beguile and deceive them all. They would build many magnificent churches with lofty walls and towers and steeples and much stained glass, but there would be no faith in them, just people going in and out daily to admire the noble architecture. They were tombs of the dead, not living edifices of faith! she said. Then she went on about the people who were mired in immorality, luxurious living, sensuality, endless pursuits of pleasure and even perversity. This city would rise to such heights of influence, birthing emperor after emperor, that it would pollute the entire world with its ways. Its fashions in clothes, building, arts, and luxuries of all kind would dominate the souls of countless men and women. Palaces of a size and splendor unequalled in the world would cover whole sections, and mighty triumphal arches and avenues would make this city the most beautiful on earth. But with all the beauty, wealth, fashion, and luxury, the wickedness would increase all the more. Rebellion, anarchy, and godlessness would become a brutal, bloody religion to replace the one that had build the great basilicas--and this godless religion that worshipped man and anarchy would fill the public squares with headless bodies and baskets of severed heads. Worse was to come yet. A world war would erupt, but even that was not the end of evil. Serving as the site for the most treacherous treaties, Paris would host a conference of the triumphant king, who would impose such brutal vengeance upon the defeated nations that they would provoke mass slaughter of all their peoples in yet a greater war that would sweep across not only Europa but the entire world, killing many tens of millions of people, including six million of the Lord's Chosen People the Jews, and--Honorius's head swam as he listened, and tried to keep his eyelids open.

She mentioned some lesser far-future despots, naming them D'Estang and Mitterand and Sarkozy, who betrayed their country and their people into the hands of those who wished to rule all Europa as one realm, even as Roma had once ruled it--only they would rule with an iron fist of such cruelty and inhumane spirit that even Roma under the mad Caesars after Caesar Augustus would have been appalled if she had known of it...

Nudged several times by his father, he tried to stay awake and not topple over.

"This city will be called 'Paris' one day," she said. There was a stir in the assembly at the barbaric sound of it. 'Paris'? After her licentious, half-converted tribe? How could that be? Were the Romans going to permit that? It seemed to be impossible. The Parisii were hardly of such power and number that their name would be chosen to supplant the city's proper Roman name, everyone naturally thought.

But she repeated the name. "Yes, that the name the angel told me, for he said the city will someday overflow with the ancient wickedness of my people, who were lost in the sins of perversity and adultery and all manner of lusts since the most ancient times, and Paris will continue that way shamelessly until the Lord comes a second time his people free."

When the woman had finished, it was just in time, for Honorius was then falling forward, but the assembly standing sudddenly to its feet caught him, and he stood bolt upright with them.

Yet the meeting was not over! Several men and even another woman spoke in turn, speaking in tongues and then interpreting what was spoke in unknown languages from the Spirit of God.

Honorius, miserable by now and wanting only to get out of the church and get some fresh air, heard only scattered phrases of the prophecie that amplified the vision and cast its light upon distant ages and British peoples yet to be born.

"The land of the many tribes of the uttermost islands of Britannica will see a great light. Bearers of this word are present in our midst that spring from the loins of most ancient kings. One here shall stand with the Lord's apostle, by the name Patricius, in that latter day, and help in the work of that great man of God, so that an entire people of warring tribes bound in the shackles of the Devil, worshipping every foul demon and idol and drinking continually and committing adultery and every evil deed, will be set free and cleansed of all their iniquities and walk in the light as noble sons and daughters of the Living God! Only long after will the people again turn back to their filthy idols and serve demons of lust and pleasure and power and wealth, and again be shackled and bound in darkness, with all their churches empty or shut up or turned into granaries and drinking houses. Lying, wicked, silver-tongued men, Gordon Brown and Tony Blair by name, will be the false shepherds who will lead Britannica's people back into abject slavery and bondage, casting away even their nation for the sake of a government over all the earth that will only act to crush them under. Yet even then I the Lord will hear the cries of the oppressed and remember My people and preserve a holy remnant among them, and not suffer all to be destroyed in their sin and rebellion."

So the woman's vision was affirmed by the continuing testimonies, and then it was over. As they all filed out, Honorius was so glad he was free at last, he hardly noticed that his father was talking with a deacon who was walking with him down toward where they had their horses quartered.

"I really can't say we are the ones, sir!" his father told the man. "I am open to such a thing, as I believe the woman's vision, but I am not an evangelist as such. Could it be someone else present in the assembly today?"

The deacon shook his head. "We have inquired, and no one else from Britannica was present today but you and your young son! Then we are all bearers of the holy evangel, if we are God's true children! Maybe it will happen in years to come when we are all gone, but it is going to happen, for these were true visions and prophecies, as all the elders have confirmed them." said the deacon. He lay his hands on them and blessed Honorius and his father, asking the Lord for their safety throughout on their long journey, and with that as his farewell, along with a basket of food, sent them on their way in the name of the Lord Yeshua.

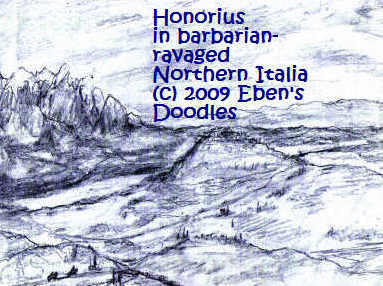

But central Gaul was not in as good a shape as Rufus Quartus had wished, for they saw some very disturbing things. Once a splendid province that Julius Caesar had conquered from the Gauls and filled with Rome's civilization, raids from barbarians had driven away much commerce and spoiled a number of cities and towns, leaving them desolate with only a few wretched people picking amidst the ruins for something useful. The roads had once been full of traffic night and day, crowded with tradesmen and agents of mercantile business, and imperial mail couriers, not to mention the sight and sound of legions with their bugles blaring time for the march of countless feet and horses' hooves and war wagons. All this made for lively, thriving tabernae and inns, shop keepers and stables, not to mention farmers who could easily sell whatever they had to passers-by. Now the roads stretched empty through barren, uncultivated, once populated and thriving but now wild countryside, with only occasional retreating garrison troops drawn from outposts that were being emptied in the face of advancing barbarian hordes. Goths! There seemed to be no end of Goths! They came by many names, but they were all barbarians, greedy for Roman lands. Refugees too were seen, in decreasing numbers, for most had already fled southwards, leaving vast areas, even entire orchards, farms, and vineyards open to brambles and weeds, with the return of the wolves and bears and robber bands. Barbarians had already left their mark, in burned temples and ruins of villages and towns and villas. What inns were left were few and poorly run, charging high prices for filthy, lice-infested beds and wretched food. Horses could not be had at any price.

Honorius's pater was upset by what he saw, but he told his son things would improve when they crossed over the mountains and got to Italia proper. There things would be fine, with all things done according to law and order.

Coming upon a ruined temple that his father recalled, they went up to view the ruins more closely, leaving the horses.

"The sight makes me very sad, my son. It was once a temple of the pagans, with the foul idols of the Greeks in it and a lot of temple prostitutes, both male and female. But that passed away, and a church cleansed the premises and met there, a church established by apostles on their way to our own Gloucester in our own country, and I worshipped the Lord in it, when last I rode this way," Rufus told his son. "But there is no sign of the church now--nothing--all gone!"

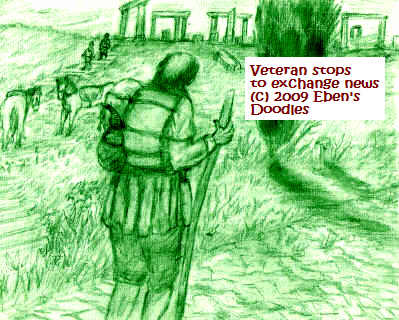

A lone figure appeared on the road and stopped, watching them touring the ruins and then start back to the road.

Honorius's father drew his sword and approached first, but found the man, after a few words, was a veteran of a disbanded legion, his head balded by long years under an iron or brass helmet in the burning sun. He sheathed his sword.

He gave a rueful look at his own lone sword.

"Who might you be, sir?" replied the veteran soldier. "I see you are of the curial nobility, from your fine garments and insignia. I can also tell by your accent there is some connection with my own homeland and native speech."

Honorius's father introduced himself and his son. "I am Rufus Quartus Urbanus, and this fine boy is my son Honorius. Our forefathers' country is Britannica, and our city is Glevum on the western coast. Do you know of it? It is a small but pleasant city. And you, my man? What is your name?"

"Decius Sylvannus Flamminus--that's what it was properly, though I don't go by it--for the Emperor Decius was very cruel to us legionnaires, without cause, decimating an entire legion in Achaea just to kill the Christians in it who refused to worship him as a god, so when my men saw I did not like it, they called me "Lancio" commonly, for I was always best at throwing the javelin rather than wielding a sword--as I never missed with it. I am from your own isles, and though I know little of your coast, I can tell by your speech you are from there too. Fair and pleasant Britannica of the many green isles! How fares she? I have been many years fighting with my arms and strength, serving in the legions of Italia and also those in the East that fought for this and that emperor favored by our legions. But that is over! All my strapping, brave lads I left Britannica with--they are all gone! We were tens of thousands, bursting with pride of country and zeal to win fame and fortune in the Emperor's service! Alas! They are not returning to their home isles, they were slain in heaps far from home, or perished of sickness, or went into service for some other general than the one we started with. The others have retired to a city in Syria Majorica. At least my own land is still held by my name, located in a village nearby the big river and Londinium's fort, wharves and shipping, however much it has been changed from the one I knew as a youth, will be better. Or is it altered to my loss, ravaged perhaps by barbarians?"

Honorius's father assured the old veteran it was not altogether changed, though the land was drained, bled white of its farmers that made good, strong fighting men, having lost them to the constant demands of the legions and the emperors.

"Now concerning this new emperor of the West, the youth Honorius, is he a fit ruler of the Romans? Or is he weak-willed, and the barbarians can get the best of him? I go to attend to business I have in Roma, as I deal with spices and pepper, and the emperor's chief baker was a chief client, and he no longer answers my letters I sent to him."

The veteran paused to spit to one side. He wiped his mouth with his tattered sleeve. "Your court baker may have no business to give you! Or he's left the city for Constantine's City. Our West Emperor, a feeble willed youth, has quit Roma, if that will do him any good. He doesn't dare reside there anymore, says it cannot be defended, even with the walls and forts round about it. No, there is little hope for Roma with him at the helm. You see this--that has happened since he ascended the throne, and he and his counsellors did nothing to prevent it, nor will they prevent worse in the future."

Honorius looked up at his father's face, and it seemed to turn gray in a moment.

"Quit Roma? The immortal city of the Caesars with no supreme ruler? Where has he gone then?"

"Ravenna, the fortress city in the swamps of the River Po which you can only reach by boat! You must sail up to Classis on the northeastern coast, then proceed west from there to it. I've seen it once as we set guards and delivered boats with masons and stonework from the port. He can have it! All he's got is his big palace and a lot of slaves to serve him, and what gold he could carry out with him. That's where he's run, with the whole court! Left the rest of the Romans and the whole of Italia wide open to the barbarians! What a country this is now, with no proper rule over it. No wonder it looks like this wretched area!"

After speaking a little more, Rufus thought of something, and it shone in his face. "Lancio, I have an offer for you, for I perceive you are a good, honest man in your heart and ways. I did not know the roads would be this bad, and the barbarians so numerous in the country, so I did not take my servants for guards. For my boy's sake, I would like you to attend us, to Roma and Ravenna and thence homeward. I will pay you well. Will you be willing to interrupt your journey to aid us in ours? Think about it, and give me your answer.

The veteran bowed, lay his sword and javelin before Rufus, then rose and grasped hands with him, and the deal was struck. Honorius, amazed at what he saw, had to be nudged by his father, and then he hurried off to get their mounts.

Lancio took Rufus Urbanus aside privately. "Lord Rufus, I did not say all, for I did not wish the boy to hear this, but I have a further reason for accepting your offer of work. It might frighten him, and this is a trip he should enjoy, for it will remain long in his memory."

"Oh? What is your full reason, Lancio. I think I can bear to hear it."

"You must have heard along the way here, but the Goths passed through Gaul and Cisalpine Gaul a while ago and then ravaged the provinces and cities of Spain, burning, looting, raping the women, enslaving the ones they didn't kill, the length and breadth of it. The savage horde loves nothing better than to burn and destroy the fine Roman things they cannot make themselves. Their commanders led by Alaric have bided their time like wolves in a den, plotting their grand venture, hatching their schemes, until they have gathered enough arms for their forces, to capture and sack the city. I do not believe they will be stopped. Though the legions cannot be beaten if led properly, there is not the will in the young Emperor to lead with courage. Nor will he send an able general to do what he is afraid to do."

Rufus paled. "I regret I named my son after this emperor, if he is so weak in the knees. When will the Goths do this evil? Who told you these things?"

Lancio smiled thinly. "Soldiers of my age have acquired many, far-ranging ears and eyes common citizens do not have. We take care of each other, too, and so this warning passed to me of what is happening with the horde advancing from the north and east (for they split into two main wolf packs, the Visigoths and the Vandals of the far north of ice and snow. We have followed them and kept track of them all the way down to Carthage. So we know They will soon be coming for Roma which is the grandest prize of war they aim to seize, but we should have just enough time to see it while it still stands in its glory. We do not have time to waste, for your son to see it and you to conclude the business you have there. I will attend both to the city and our own home isles."

"You will ride my son's horse, and he will ride behind me on mine. That way we will make better time to the next stop at an inn or city."

He turned to Honorius, who had sharp ears and had caught some of the exciting talk about the barbarians.

"Hand Lancio the reins, son. I am giving your horse to him, as it befits a man of his worth to ride his own horse, not one that is lent to him. You will ride with me until I get you another mount."

Honorius's face fell, and he reluctantly gave the reins to Lancio.

"Bow, son! Be noble and civil as I have taught you to behave to your elders! He is no slave of yours and mine. He is a freeman, a citizen, and I have hired him to be our guard on this journey, so respect him as he deserves, he is a veteran of many campaigns of Roma's legions, defeating the barbarians on the frontiers and keeping our country safe!"

Honorius's eyes widened, and he gave a deep bow, and Lancio chuckled.

"When there is time on another day, I will show you my javelin and how to throw it!" he said to the boy, and Honorius brightened up, smiling.

"Yes, I would like that, sir! I don't want the sword first. Teach me how to throw your big spear a long way--a whole mile! I want to kill a hundred of the Goths!"

Then Rufus Quartus Urbanus, also chuckling, pulled Honorius up behind him, and they made off toward Roma, with the veteran going ahead, as he had better knowledge and would know where they could safely stop and rest for the night.

Rufus, seeing they had no other choice for the night, asked to stay the night with his son and retainer. "Do you have lodgings for us?" he asked. "I regret we have come upon you so late, but we came not knowing things would be so disturbed by the barbarians hereabouts and--"

The man nodded. "Please enter, sirs," the man said.

"How is it that the table is all prepared?" Rufus Quartus Urbanus asked her in his amazement.

"We have been expecting you, sirs," she said, bowing

She gave them her name, Prisca.

Rufus Quartus was very much surprised. "Howso, woman? We are coming as utter strangers at nightfall, and you were expecting us?"

She smiled. "Yes, sir, it is the truth I tell you. The Lord told my husband and me that we would have late guests, saying there would come a noble gentleman, and a soldier, and the noble gentleman's young son. So knowing the appetites of hungry men, I kept the soup kettle warning near the fire tonight, and there is some good meat stew too, and pastries and wine and fruit to go with it. It is not much to offer you, but it is all we have, as our farmers and their livestock have all moved away. You see, the country is very much forsaken now here, the many vineyards eaten up by the birds and the wild goats, as the barbarians have come so close, and might break through any time to burn everything, as is their custom."

Rufus frowned. "Yes, so we have heard and seen! But this is dinner enough. Let us sit and refresh ourselves, and give thanks to the Lord for it!"

After handing their cloaks and gear to the man and woman, they sat at the table and gave thanks first and then ate their simple but filling dinner. The innkeeper's wife stood by to refresh the glasses with water and wine, or bring some more linen or additional bread, and after a time Rufus Quartus Urbanus turned to her.

"So you are disciples of Christos here? I am so pleased by what you said. To think the Lord speaks to you like that! Even telling you we were coming!" "Yes, otherwise we would not dare to remain alone here after all the others packed up and journeyed to Roma and elsewhere where there are soldiers to protect them."

"But why do you remain? Your business cannot be good, with so few passers-by on the road nowadays and so many bandits to scare and hurry any patrons away."

She glanced to her husband, who exchanged it. "We wait on the Lord, for the time we are to go. We trust in Him to protect and care for us. He is the Good Shepherd. He will not permit us to remain a moment longer than is good."

Rufus turned to his son. "Remember that, son! Our hosts speak well of the faith. God has our lives in his hands. No matter what it looks like, he is God. He is over all!"

They slept well in clean beds. Only Honorius tossed about on his pallet, for he was dreaming of fierce battles with the Gothic barbarians, battles he and his legionnaires always won handily. Afterwards, as a champion of Roma and the Empire, he was paraded in a Trumph in a big golden chariot, with the emperor standing at his side, passing with thousands of captive barbarians in chains through the streets of Roma while the multitudes cheered. That was wonderful! Yet always there was a voice of a man at his shoulder, disturbing his mind and spoiling his success, hoarsely whispering: "Remember, you are but a man and you will die!"

"What do you mean?" Rufus protested.

"We are to take nothing, sir. Please go on your way, with the Lord's blessing!"

Rufus could not understand how they could do this. "But--" he said. "Sir," Prisca said, "we are old and childless, and have our life savings, and need no more earnings to keep us in our last days. In the night, the Lord said for us to pack what we want to take with us, and go to the church we will find in Smyrna of Asia, so we are going now. You are last patrons, and we could not possibly charge you anything. Please accept it from the Lord."

This was so unheard of, but being a Christian, dealing with Christians, he understood, and nodded.

Outside, as they were brought their horses, all fed and groomed and watered and ready for the day's journey, Lancio turned to Rufus, bowing, with an amazed look on his face. "I have never seen such things! How can they not charge us! Surely, they are daft with old age!"

Rufus Quartus smiled, then mounted his horse, thanking Prisca for the wrapped package of cheese, dried meat, and fruit she handed him, free of charge. "Lancio, there are more things in Christianity than your religion knows of! You will learn in time what we have in Christos. Bear to learn them in time."

Both men were surprised when Prisca came hurrying back with a white horse, a mare, from the stable, all ready for its rider. After bowing to Rufus Quartus Urbanus, she handed the reins to Honorius. "I see you could use another horse, sir, for a more comfortable journey!"

Rufus reached for his money bag, but the woman shook her head. "No, sir, that is not necessary, as the Lord told us to give you this horse. We have no need of it, as we have two remaining, sufficient to take us on one while the other carries what little we need to take with us for our journey to Asia."

Now all three travellers were astounded. This was simply too much for Lancio. "What kind of faith is this, that you give away such valuable horses as this one, to utter strangers! Even I had to walk, having had to give up my horse to save the expense of keeping him on a long journey. I desire such a faith, which I have never seen before. Surely, you love each other beyond what anyone in my religion loves!"

"We have been given much, so we cannot help but freely give. And the Lord commanded us. We seek only to obey and please him by helping strangers such as yourselves on their way."

"'Lord'--who is this Lord of yours? I know Mithras, but he is not like your Lord, and you are not like his followers. None of them act as you do! They do not have any such love as yours! I want to know your Lord as my own."

A little while later, it was done. The innkeeper and his wife, who had been among the elders and leaders in a local church, with Rufus Quartus Urbanus and Honorius, witnessed the renunciation by Lancio of his pagan god Mithras and his expressing belief in Jesus Christos as his Lord and Savior, and then they baptised him in a large pond behind the inn that was spring-fed, out of which flowed water to the nearby aqueduct.

Lancio emerged from the water, shaking off the water from his hair along with a few water weeds, and looked extremely happy.

"What do you say about this?" Rufus Quartus asked him when he was standing, drying off with a blanket and towel brought to him. "Do you feel different? Are you changed?"

"How do I feel? Better than I ever felt! It is like I was a baby new born! Even the leaves seem more green and the sky more blue! I feel also a wonderful, burning in my chest, around my heart, and it is a good feeling. It is glorious--what is it?"

He slapped his chest with his hand.

Gratian and Prisca smiled to each other, then proceeded to instruct the brand new convert to Christos.

"The Holy Spirit has put the Spirit of Christos himself into you. You are now born anew by His Spirit. You are now a child of God, a heavenly being that happens to live on this earth. All the promises of the Word of God are yours too! Read the Word, son, and be instructed in holiness and righteousness. You must read the Word of God faithfully and pray. It will keep you safely to the end, when your soul returns to God who created you."

"What Word of God?" Lancio asked Rufus Quartus when later they were on their way again. "I want it!"

"I will show it to you. You yourself will see and read it at the next city after we stop there for the night."

Just beyond it, they met the first signs that the country was once again under Roman rule, with anarchy dispelled. People were moving about freely in the countryside, as though they had nothing to fear, and wagons carried produce and livestock for the markets of the city Rufus Quartus was approaching.

This was an encouraging sign. They found it even better when they sighted a garrison manned with a full complement of troops, both infantry and horsemen, all fully armed and ready for any barbarians that might show up at the gates or seek to ravage the farms and villas outside the city's walls.

Here Rufus Quartus dismounted, to get some news from the garrison, Honorius, with Lancio keeping an eye on him, went to take a close look at one of the soldiers standing duty.

"I have no need of it anymore, Master Honorius," he replied, trying to restrain a chuckle. "I am not in the wars now, and I am no longer young, so it is time to lay down my arms and go back to farming."

Honorius's face showed his disappointment. "But why--?"

Lancio shook his head. "If Roma calls me to defend her against the Barbarian, then I will gladly return to the ranks, but not until then. I have served and done my duty these 25 years, and am discharged. I have land now to till and restore at home, and there I will go to spend my later years." He almost added piously, "by the gods!" but caught himself, reminded that he was serving the Son of God, not Mithras from the east and the old gods of Rome and Greece.

The cities and towns were still splendid-looking overall but it became obvious even to Honorius at closer quarters that many great buildings in them were dropping masonry into the street or standing abandoned, and no new ones were being erected in their place or repairs being done. Also, shops were boarded up, with the owners packing everything aboard wagons carrying 1,200 pound loads of merchandise and belongings. Where? To the great mothering metropolis of Roma of course, if not straight to Port Ostia! Roma still seemed the only place left that was safe--at least to people's minds it was safe, being so big and populated it challenged by its very size all but the greatest enemy forces. Even then Roma was not going to be an easy conquest. That the Barbarian could ever breach the walls built by Aurelian, that circled the entire city with forts and garrisons, was unthinkable.

Moving through the markets and squares of the cities, Rufus Quartus, Lancio and Honorius could see clears signs that many people were going hungry too. They found many beggars in the streets, reaching out to them for alms. Christians had alms houses going, which were jammed with the poor. And yet there were more that could not get in for help. The slave markets were also jammed, as many men had sold their hungry children into slavery, rather than see them starve. Even freed men, citizens, sold themselves too, rather than starve. In one of these markets, Lancio halted, staring at a particular man who was offering himself as a slave, though at his neck hung no scroll giving his name, age, and health. In evident poor condition, he should have drawn no interest without the required titulus, and indeed he drew no eye until Lancio came.

Rufus Quartus Urbanus noticed what Lancio was doing, if not knowing why, and stopped Honorius, and they waited. They watched Lancio go to the man and take a closer look, then return to Rufus Quartus.

"What about him, that fellow without a titulus?" asked Rufus Quartus Urbanus. "He looks like any other wretched man in his condition, does he not, Lancio?"

"No, sire, I see something different about him. Look at his face, how pale it is! Something is different. His eyes too, they squint, as though they are not used to the full light of day. I am certain that man has been a miner, a slave in the mines!"

Slavery in the mines was a death sentence for criminals, they both knew. Speaking in low voices, Rufus Quartus continued. "Well? If he has somehow escaped and run off to this city, he has evidently found nothing here to sustain him so he is going to sell himself back into slavery. He is going against the law and may be he murdered someone, and was sentenced to the mines for life. Maybe he will succeed in selling himself now, maybe he will not. Give him this for a good meal at least. He looks as if he has not enjoyed a good meal for quite some time!"

Rufus Quartus held out several denarii, but Lancio declined, bowing.

"No, sire, he is not like that. He is not just a runaway criminal slave only. I can tell somehow. There is a good man in him. Let me go and speak to him before we leave him to his fate."

Rufus Quartus Urbanus nodded, and he and his son waited for Lancio to speak to the pale-faced, squinting man on the slave auction block.

Rufus was a bit shocked. "You mean to buy him then as your slave?"

"Unless you prefer to have him, sire, I will take him. He will come with me after our journey is over, to help me attend to the work on my farm. He says he has no family still living, as he already inquired in his native town and found they were all gone, his parents dead and his brothers scattered to distant parts he cares not to go. None of his parents' neighbors were willing to help him, nor would they give him any food or shelter. Without relatives or friends, he had no choice but to seek any work he could find in the country, he said, but there was nothing--as we ourselves can seee. Everyone is leaving south, for Roma, abandoning these places, so they are not going to taken on laborers when they are going out of business or leaving their homes and properties! He was starving when he thought to do what he is doing, go sell himself in the market to some landowner or tradesman, rather than slowly starve to death."

"But what did he say about his being an escaped criminal? What was his original crime? Did you ask him that?" said Rufus Quartus.

"We should be breaking the law if we gave him shelter, when the state may still be looking for him." "I did ask him. First about his escape. He said the barbarians raided the imperial silver mines in Hispania, and killed all the guards, so the slaves used the mallets and other tools, broke their shackles and ran off. The barbarians were more interested in silver than slaves anyway, and took all the silver that was in the guards' strongboxes and then departed, rather than make the slaves dig for more. He was free! No guards came to replace the ones lost, as Roma could not spare any to send to retake the mines and round up the slaves--and besides they had no rule over that area once the barbarians ravaged it. It might be years before Roman rule returned. What could he do? Wait until then? No, he decided it was best to save his life if he could. He would not stay there, which was a place to die only, but try to make it back to Italia. And he succeeded, only to find the conditions very bad, even in the ruled parts. Concerning his crime--he when a mere boy struck back at his master who was brutally beating him, who had accused him of stealing a necklace of his wife's. He said another slave had done it, and cast the blame on him. The master did not care which slave really did it, he took the first slave's word, since he was a grown man. To escape worse beatings, he then fled to the authorities for justice, but they too upheld his master's judgment, and since his own hand was raised against his master and he was nothing but a slave boy, that was sufficient to send him to the mines for life."

Rufus Quartus Urbanus turned to the slave and took a keen appraisal of him and the expression of his face and eyes before he spoke. "You are most fortunate you were not caught and branded fugitive on your forehead and returned in chains to the mines! Or they might have cast you into the galleys. Heaven has smiled on you! I greet you in the Name of Christos. I am Rufus Quartus Urbanus of Glevum, Britannica. I have heard many similar stories, but I believe the report you have given us. Lancio is now your master, for he has paid your stated price. Later, I can have a proper document drawn, when there is more time. I will not require anything of you myself in service. Do whatever he tells you to do from now on. I know he will treat you well. We are all Christians in this party, and we cannot mistreat you, or our Lord will punish us for our mistreatment of an unfortunate man. As for your past, whatever put you in the mines, it is over, since you have paid your sentence as long as you could. The barbarians freed you, as God's instrument evidently. I have heard what sad circumstances put you in that place, how God set you free by way of the barbarians. You have chosen to serve your master, Lancio. A horse will be provided you, for we must travel quickly to Roma and then return home to our native land soon thereafter. Now, what is your name, for you bear no titulus?"

But the man could scarcely say his name, Gaius, in an audible voice at first, he was weeping so uncontrollably as he saw how heaven had indeed smiled on him to send such kind men his way.

Honorius was not so sure it was heaven! His expression showed it plainly, that he did not at all like the idea of this dirty, half-skeleton coming along with them on their journey. He would spoil it all! he thought.

"Does he HAVE to come with us?" he asked his father plaintively. "I don't like his smell and his looks. He is so old and dirty and just a pile of bones! What good is he?"

His father's face showed he was not very happy with his son, and he took him aside.

Rufus put his hands on his son's shoulders and looked keenly into his eyes.

"Remember this, son, and never forget it. You and I are no better than any slave, we are all flesh and blood, our substance drawn up from the dust and fashioned by the same Creator. He has dignity, the image of God just as we have, only his circumstances are unfortunate, as you can see. That is not necessarily his fault, I am informed. Even if it were, our Lord the Christ forgave us sinners our many trangressions, so ought we to forgive others their transgressions. Now I don't want to see that unmanly and unchristian look on your face again! You have nothing to be sorry about! He will be a big help to Lancio and us too, after he has gained strength with some good meals and had a hot bath and a new set of clothes! You'll see!"

Honorius was almost beside himself, but he didn't dare show any more displeasure at his father's decision, so he screwed on a smile of sorts, and his father let him go.

After the fourth member of their group was taken care of in the town, they continued their journey. But at the next city, Praeneste, once a thriving Etruscan center but even in decline remained wealthy and of considerable importance still to the West Roman government, there resided a consul that Rufus Quartus Urbanus knew personally, since he had been assigned to Britannica in years past. He paid a call on the consul at his government house and were led into the consular hall, waiting until they were announced and told to proceed. Since being moved from Roma to the this city for its better security, the office had done the emperor's business for the whole of that region. It did not take a long wait, as the hall was virtually empty of business and people at that hour, and Rufus Urbanus's name was well known to the consul.

With unpleasant things out of sight, Honorius could turn to more interesting sights. Having lived all his life in a great house such as this, he knew the most interesting parts.

Rufus Quartus Urbanus was shocked.

"But this is your country! You are not Greek-speaking, and surely you will feel ill at ease among the Eastern Romans! They scarcely speak a creditable Latin, I've heard, nor do they care, since they prefer Greek far above our mother tongue!"

The Consul's smile faded. "It is absolutely necessary, my friend! I will do my best to learn their Greek with the best tutors I can find. When Roma draws back from any area, the country will soon turn savage wilderness. But worse will soon fall. The tribes of the Goths, hearing of the exposed weakness in our borders and defenses, will break through and ravage what is left. It is only a matter of time before they return for booty and level such cities as Praeneste. Radagaesus destroyed three quarters of northern Italia, destroying hundreds of towns and many cities, and now he or others like him are moving westerly again with their hordes, intent to seize and ravage the central parts of Italia, and maybe even take Roma herself if they quit their rivalries and combine into one army! No, we must go, it is now or never. Otherwise, what is there for my wife and me? We will be left refugees, vagabonds, with no imperial office, no future at the imperial court at Ravenna either since the emperor's family was always a bitter rival to my own in past generations. We will possess only what we can carry away with us if we happen to elude the rampaging Goths! We cannot remain!"

Rufus Quartus Urbanus bowed, but declined. "I have no time to spare, sir, for such a gracious favor of yours, but I should like to greet your wife for a few moments, since it has been years since I have last spoken to Lady Julia. And I know my wife will be cross with me, if I do not seek to exchange a few words with her. You know how wives are always interested in each other's families and situations. Is she as well as ever?"

The Consul's face seemed troubled. "Yes, she is well, and looks well as ever, but she has never borne children, which is a sorrow to her, and of course I would have liked to sire a son or two to carry on our family name and serve Roma in imperial administration or in the officers corps of the Army. But it was not to be. We are no longer young, so children are not going to be our blessing, it seems."

But the sad look partly left his face as he turned, and saw his wife was approaching.

"Here she comes now. Please stay for dinner and speak to her. It may give her some diversion, as there is only myself and the servants usually these days. We get few visitors of any note."

Rufus Quartus Urbanus turned and saw the aristocratic lady of ancient Roman family (one of the Gracchi) waiting at the edge the consular hall, and he decided he must take the time to speak with her. Anything less would be disrespectful and most ungracious, considering how many times he and his wife had been invited to the consul's fine villa just outside Londiniuum.

He found her as lovely and delicate as he remembered, as the consul led him up to her, but there was no happiness in her expression, only a kind of patient resignation in the face of a hard, inescapable destiny. The jetstone miniature of her husband at her neck, and the jetstone ear pendants, they went along with her fatalism, he thought. Didn't they have any hope of the Resurrection? Perhaps he could share with her something of his faith, just as he had done with her husband on previous occasions. He knew there might not be another chance, as they would not be meeting again in this life, he knew. Britannica, he loved, and he could never leave her, whether Roma abandoned his country or not. As for New Roma, he knew he would slowly wither there in a gilded cage--better to face the barbarians in the West than feast amidst the sophisticated Greek-speaking "Romans" of the East, blue-blood courtiers and officials who would never accept him and his family as their equals, since the Urbani, like all British nobility, were originally Celts and provincials with only a few generations of Roman civilization to their names! What would they care if he told them his family line sprang from kings--they would smile at him and detest the thought that barbarian kings were anything to be proud of! No, rather than endure such humiliation and the slights of courtiers, a rustic but dignified obscurity in Glevum was much preferable, and so he and his son and Lancio and his servant were returning to Britannica as soon as his business with the pepper imports was finished in Roma!

The lady laughed, yet her husband the Consul looked very serious. "It would be more likely for you to come our way instead. We doubt we will see the Western Empire again--it is going into such bad hands these days, there may not be much left of it in a few years. The barbarians--"

She looked off, and her husband frowned. "But I am not a very good hostess, reminding you of such unhappy things!" she said, brightening up a bit. "Won't you please stay and dine with us? We have so few guests ourselves these days since we were relocated all this way from Roma. Imagine, no consul residing in Roma--who could have imagined such a thing!"

Rufus Quartus Urbanus bowed, but declined again. "It is most urgent that we reach Roma and conclude our business there. The pepper fleet is in, I have been informed. I must speak with the captains and the collegia and the others in charge of the trade, to insure that Britannica receives its yearly allotment according to the imperial edict. If I don't catch them this time, it may be years before we get the import trade re-established on former lines--as we have had to make do with such scanty stocks of pepper the people at home are growing very unhappy. As a middleman for a league of cities, I am held responsible by all parties, even if I am not making any profit at the end!"

He reached up and grasped the rein as Rufus Quartus Urbanus mounted his horse. "One question, my friend, will you grant me that? We may not meet again in this life."

Rufus Quartus Urbanus's eyebrows raised. "Yes? Is it as serious as your expression tells me?"

"My wife cannot conceive. We have tried for years, and now we are nearly past the age, I think, for child bearing. It is a hard thing for my wife particularly, even if I lack a son to carry on our name and inherit the properties and servants. Here is my question. Is it true your god, your Christian God, is a healer? I heard tales that he has granted children to the barren women in your assembly. Is there any hope for us in your God?"

Rufus Quartus Urbanus spoke very quietly with the troubled Consul for a few moments, and then prayed for him. Urbanus saw it was time to go, when he saw that the Consul truly understood the reasons for faith and how to become right with God, and they moved away. "Let me know by imperial post whether God has answered my prayer!"

The Consul saluted him. "Yes, I will. And I and my wife will believe God, believe Christ his Son for a child, as you instructed me to do in faith! We will follow His way. Farewell!"

"One last favor I ask of you, my friend. Would you give this to the imperial post, my friend? My wife will be anxious to hear of us." Rufus Quartus handed the Consul a scrolled letter.

"Certainly, in the very next post! And I will put my own seal upon it, so it receives the most protection and arrives under guard as far as Gesoricum!"

Rufus Quartus bowed his head, then turned his horse, and his son followed. Praeneste, awaiting destruction by the barbarians, seemed a sad place, with no prospects despite its look of lingering grandeur and wealth, and Honorius felt better when they had put it out of sight behind them.

Honorius climbed inside an even larger carriage, the carruca. It was a sleeper and contained a splendid bed with pillows, with blinds to close off the light from the windows.

"Couldn't we get one of these to use, Pater, instead of riding horses?" he asked. "It would be so nice traveling in one of these! We wouldn't ever get wet or cold again. And there's a place to sleep and eat in them too!"

Rufus Quartus chuckled. "All you would be able to do is sit or lie down, you would soon be bored with traveling! Besides, you are not as high up as on a horse. What is a little wet or cold? It toughens a man, rids him of his softness, so he can endure whatever hard things life brings. No, it is best to see the country as we are doing, from horseback, and, besides that, a carucca or raeda out on the roads blazing with gold decorations would just draw the bandits down on us, so we would require a special guard of soldiers to accompany us."

Yet it was apparent to even Honorius's star-struck eyes that something was missing--namely crowds of people. Finally, he turned to his father. "But where is the Emperor, Pater? Has he gone on a hunting trip and has not yet returned?"

His father sat him down, and looked intently into Honorius's eyes. "I see I must tell you, now that you asked. He is gone, with all his people, since he will no longer live here in Roma. It is too dangerous for him."

Honorius was astonished. "But why? Roma has great walls all round the city, with many soldiers upon them! What can he be afraid of, Pater? He has many soldiers more than these in the city, doesn't he! What about the legions?"

His father shook his head. "They are no longer enough to defend even this city, son. The Emperor knows that, so he has moved to a refuge in the north, a city called Ravenna, that is moated naturally with hundreds of streams and miles of swampland. No marching army may approach it. There's no waterway into it for large vessels either, except from Classis and the sea. There at Ravenna he and his nobles and family will be safe enough as long as they have the manned warships to patrol the river and waterway leading to it."

"Safe? Safe from what, Pater?"

"The barbarians, of course, who cannot all be stopped. They cannot beat our legions man to man, but they can overwhelm our poorly manned border garrisons at the limes with their numbers, as they are doing in place after place. Britannica has been drained, bled white, losing the best troops Roma could muster, most all were fellow Britons too! They'll never return home to defend the homes the left, not in anything like the numbers they departed, to fight for one claimant to the throne or another. We are wide open to the enemy now. And the other provinces are in the same woeful condition. We saw what they have already done in Gallia Cisalpine, and they will be coming all the way south to Roma next, and this greatest of earth's cities will be taken, burnt, pillaged, and maybe destroyed to the foundations. That is why I wanted you to see it now, my son, before it is swept away, or changed so greatly you would not want to see it."

Honorius's eyes fell, and he was silent for a time.

"I do not believe that will happen to this place and this city, Pater. It is too big and great for that."

His father chuckled. "Yes, it certainly appears to be. God will decide, in any case. So let us go on then."

But Honorius did not care about the Apostle Paul and his suffering in prison, it was the glorius and stupifying sight of the Roman Forum at close hand that captivated him beyond words. He was not disappointed. It exceeded everything he had been told.

He had an idea. He would run away! But what would he eat, where would he sleep? He had seen the hundreds of poor, beggar boys in the streets. They sold little things to the crowd, which dealers gave them to sell, or things they had stolen in the many big houses that were shut up by their absent owners with boards across the windows, or they just begged anyone who looked like he might have some money. Would they like it if he tagged along with them? Of course, they wouldn't! They didn't have enough to feed themselves, much less feed him too. Besides, he didn't like their smell, and the dark, filthy rags they wore, and their thin faces and clutching hands. He liked the fine, clean, purple-bordered clothes his father gave him, and the clean hot and cold and tepid water baths, and the good food and the soft, scented blankets of his bed at night. These things were necessary to civilized life. He didn't want to join the animals in the dirt! So what was he to do? He felt trapped, he couldn't live on his own without money, and his father kept all their money, except for a denarius or two that he gave him each week!

A thought crossed his mind. He could do something after all. Rise up in the night and steal the money bag, and then he'd have plenty to live on for a long time! He could be his own master, with no one telling him what to do. He would be wondrously free, like a bird is free to fly anywhere it likes in the wide sky. The thought kept him awake after he lay down in his bed and the servants had left the room. Before the dawn, he was still awake, and then he crept out of bed, careful not to wake anyone with a noise, and made his way to his father's chamber.

Honorius wasn't going to let someone manhandle him like this, so he struggled,twisting his body and pulling with all his might to get his hand free, but he felt an arm clenched around his body, lifting him up. .

He was taken down the hall, someone's hand over his mouth as he was carried. "He was going to cry, "How dare you!" to him, but Lancio's mouth was still over his mouth, and Lancio spoke instead.

"If you want your father to come and discipline you severely for this, it is for you to choose, Master Honorius. But if you will go to bed and sleep, I will put the money back and say nothing in the morning. Well, what do you choose?"

Set down in his room, he was enraged and could not think what to say at first.

Lancio repeated his offer and added the warning, "Otherwise, your father will hear everything you did, and surely you will be disciplined. Well, what is it going to be?"

In a movement too swift to see, Lancio stepped aside, seized the lampstand, and also grabbed Honorius.

Honorius felt Lancio's arm wrap around him, but he still had his head free so he opened his mouth and bit as hard as he could on the arm.

Lancio did not even flinch as Honorius's teeth sank in. Lancio swept Honorius up as though he were a pillow's goose feather and laid him on his bed, though he was kicking and struggling all he could in Lancio's iron grasp. But it was to no avail. Honorius was soon exhausted, and he began to weep. "Let me go," he whimpered. "You're hurting me."

He felt Lancio's grasp relax, and then let him go.

"So you are forcing me to tell your father? I could do that now, for you are still fighting me, are you not?"

"No, don't tell him!" Honorius gasped, getting his breath back. "I'm sorry! I didn't mean to strike at you like that. I will do what you say, sir!"

Honorius lay there, his chest heaving, trying to think of what to do. But Lancio seemed to have total control of him, for he was strong as a bear. There seemed no way to elude him or get around him. But still Honorius did not give up. He would think of something, he decided. There had to be way to get round Lancio.

"I promise I won't cause any more trouble," Honorius said as meekly as he could. "Please go now and sleep in peace. I will go to sleep now too, and you need not stay with me any longer. I am used to sleeping without servants, for I am a big boy now."

"I will not go far, for you may change your mind," said Lancio grudgingly. "Oh, no, I won't change my mind! I promised you. I will go to sleep now, just as I said!" He heard Lancio sigh, then go out, shutting the door. Waiting a bit, Honorius got out of bed and slipped over to the door to listen. He thought he heard Lancio's rough breathing on the other side, so he knew he couldn't get out that way.

Honorius had already thought of another way, which would be a bit harder, but he knew he could still do it. He was on the second floor, which let down to the garden behind the house. If only he could slide down far enough he could reach a tree beneath. From there he could climb to the ground. He waited a while, which was just before dawn, and took his bed sheets to the balcony outside his window. Tying end to end of the sheets to make a rope that he then tied to the balcony railing, he was soon sliding down to the top of the almond tree. With one hand he held to the sheet, while the other searched for a big enough branch to bear his weight. He thought he found one big enough, and swung over to it. There was a snapping sound, then he tumbled, and found himself a moment later on the ground. He got to his feet, and though his tunic was all mussed up with leaves and twigs, he felt no bones were broken. A moment later however, his arms and legs began to burn all over where the bark had scraped them.

He danced up and down, trying not to cry out.

Gradually, the fire died down, and he limped away, for his ankle seemed to have been knocked on a limb on the way down. He felt like crying, but he kept his mouth clenched and tried to be a legionarire instead. He still had to get out of the garden. Where was the back gate, if there was one? He had to find it, or else try to scale the high wall by first climbing a tree nearest the wall with his paining ankle.

His breath knocked out, he lay gasping, crawling, and trying to get to his feet. Finally, he was on his feet, dazed and cut and filthy and his clothes torn up and covered with dirt. Stumbling, with his eyes choked with tears and dirt that covered his face, he moved forward across the forecourt of a neighboring palace and didn't see what he was getting himself into. Boys as ragged and dirty as Honorius were busy running about the main entrance pavement, scrambling to grab the stolen items from the house either thrown down by the boy on the porch roof into the shrubbery or, if too fragile to survive the fall, let down by a rope in a bag.

Honorius, half his senses knocked out of him, dumbly obeyed and carried the heavy item away toward the street. There he was joined by other boys, running with their items, and they hustled him down the street, and into an alley, and between houses and, still running, led him into an abandoned building, that might have been a bathhouse at one time, for it had pools in most every room, only they were dry and filled with rubbish.

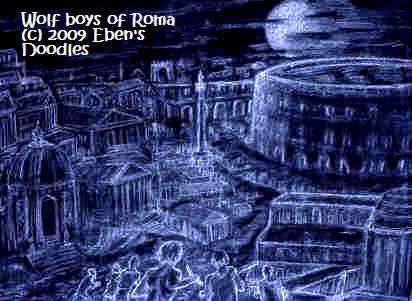

Scrambling with Honorius in tow down some steps, they entered the basement, and steps led them further down into the gloom of a buried temple of the goddess Juno, the walls covered with flaking red and gold paint and arcane symbols known only to long-gone priests. Here lamps gathered from palaces were lit and set in wall niches, and already some of the wolf boys were sorting through their loot.

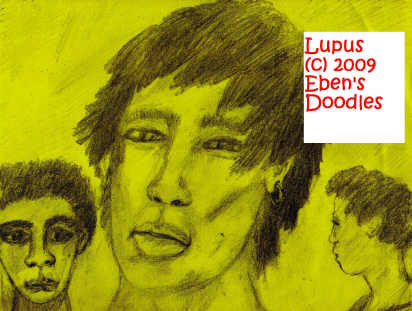

Honorius, confronted by this big, fierce boy realized he was in real trouble. Lupus had a tight hold on his arm, twisting it while he was demanding information, and Honorius, shaken badly by his falls, put up no resistance.

"Please, don't hurt me," Honorius gasped. "I didn't join your family. They thought I was one of them, and dragged me alone, that is--"

"Stinking little liar! You can't fool me! You joined in with my little brothers just to grab some loot for yourself, and then run and tell the authorities where we were located! You planned to watch us being strung up and left to hang for the birds to come pick out our eyes while the biting horse flies swarmed into our nose and ears and mouths, and you stood and laughed as you watched us scream, and twist and turn--right? I've seen your kind often enough. I will make a real lesson of you, so that no one else will even think about trying it again on me, the king of half of this city! Rats, each as big as my thigh, will be eating you in the Cloacus Maximus come this time tomorrow!"

"But I vow to you on my sacred honor, I'm am not a thief!" the terrified Honorius protested, but no one would listen to him, and jeered him all the more he defended himself. Lupus dragged Honorius over to the altar, then lifted him up and slammed him down on it.

His breath knocked out, Honorius was helpless, and Lupus and his cohorts quickly bound his hands and feet, so he couldn't resist even if he wanted to.

"Your father?" jeered Lupus. "Who, I pray, is your father? Just because you have one, you needn't be a crybaby about it--he's not going to rescue you from me, at any rate."

Now Lupus was enraged by Honorius's mere mention of his having a father. None of the boys could point to theirs, in fact. Lupus especially had no one father he could name, as his mother, a prostitute, served many men, hundreds over a period of a year. Then one day she was beaten to death by a drunken legionnaire, and he vowed to avenge her death any way he could. Casting his lots in with the wild boys of the streets and gutters, he went to live with them under bridges, in abandoned houses, even in tombs, wherever they could find shelter in the terrified city where multitudes of poor people were crammed in, trying to avoid the dragnet of the Goths as they swept closer and closer to Roma with their barbarous armies.

He had run with street boys most of his years anyway, so it was no new thing to him, to have to fend for himself this way, using only his wits. But he now has leadership over other boys, who were all in the same condition--being fatherless and motherless orphans. The authorities were brutal, and ever so often would make a sweep of the streets and their other haunts, killing as many as they could catch and throwing their bodies into the Tiber, so they had to be always on the alert and ready to flee the soldiers.

Lupus hated the legionnaires especially. In fact, he had a passion that consumed him, that one day he would do them the greatest harm he could. In the meantime, it gave him satisfaction and something to do to organize the boys of the street gangs and rifle the home of the rich and powerful, paw through their treasures and take whatever he please, while urinating on the rest, before setting fire to the whole house. But to strike at the legions, whom he held responsible for his mother's head being bashed in with the butt of a sword and her naked body left half hanging out a window of their apartment, he had to do something greater than ransack and burn great houses. He knew the weaknesses of the city's walls were in the gates, because he knew many of the gatekeepers and their ways. They were corrupt and took bribes, he knew, and he had many fine things of high value cached away in secret places that he could use for bribes when the time came. As soon as the Goths were at the walls, he had a plan prepared, to open at least one of the gates through bribing the gatekeepers and guards, and let the Goths do whatever they wanted with Roma--burn it down after looting it, that was his heart's passionate desire.

As for this boy sneaking into his own family, he couldn't allow it. Perhaps he was a spy for the Prefect, who may have gotten wind of Lupus's plan and wanted to also smash the street gangs that terrorized whole districts now that law and order were breaking down in the city, even in daylight hours.

Following Lupus's orders, the boys ran back up the steps and then soon returned with sticks of wood and tree branches and whatever else they thought would burn. This they began piling on top of Honorius, who was rigid with horror at the thought of what that meant.

Lupus grabbed Honorius's hands, inspecting his nails and skin, then smiled. "I thought so! You're from some noble family, from the looks of your soft skin and your fine ways. You never did a bit of grubbing for money in your life, did you now?"

"What are you doing? Let me go! My father will call the soldiers to come and punish you! You will be all executed for this! Let me go!"

But Lupus held him down all the more, as the pile of wood and sticks was made to cover Honorius.

"A lamp from over there!" he barked to a boy. Honorius screamed as the lamp was brought close to his face, the flame singing his eyebrows.

"No," said Lupus, "don't burn his eyes out just yet, let him see what we are going to do to him first. Come, little brothers, come and piss on him, let him drown in our piss! I want him dampened down first so he won't burn too fast and escape from the pain."

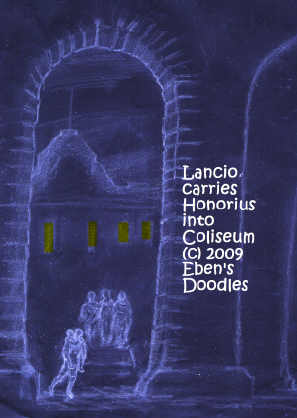

Perhaps the group was so intent on making the pyre and terrorizing their upper class victim that they didn't hear a sound of someone coming. Or the man was silent as a phantom spirit when he moved swiftly down the steps and then jumped into their midst. Instantly, he swept them aside with a big stick he carried, and he grabbed Honorius, sweeping him up off the altar, and with one hand free, fended off Lupus who came back at him with a patrician's ruby and diamond-studded javelin.

The javelin went flying as Lancio, for Honorius saw it had to be his father's servant, knocked it from Lupus's hands. The other boys had knives too, of course, and could do him some serious damage, but they weren't any more successful in getting to the worldly-wise, veteran legionnaire who knew all their possible moves before they could make them. Honorius was soon lifted out of Juno's temple and into the bathhouse, and Lancio kept going, and then they were outside in the street, with the gang hot on their heels but wary of his big stick.

The nearest large building happened to be the Coliseum, which was hard by the Arch of Constantine and also the bronze Colossus of Helios. He didn't have to think long about it, and turned in immediately at the nearest entrance.

How long would that be? It was the darkest time of night, and that meant dawn would be breaking in about an hour.

Just in case there were watching eyes of wolf boys to trace his route, he took a round about run through the inside arches and then went up a stairs and came out a vomitorium, only to cross over the stands to another vomitorium and go down the stairs, crossing yet to another stairs to ascend to the upper levels.

He encountered no police or guards on patrol. He found only occasional slaves at work cleaning in preparation for the coming day's events, with others risking a lashing by sleeping in corners, their bags of trash used for pillows. He had hoped to cross the path of at least one arena guard on nightwatch duty, but there wasn't one, they had cut back so much in their forces since the panicky emperor and his court and chief government officials and nobles fled to Ravenna and security was drastically reduced. The guard could have called for the others, and the wild boys would have been forced to make a rapid retreat. But not one showed up as he ran through a big swath of the arena.

Yet it wouldn't be long before they had to come out of their headquarters. Arena guards, he knew, would make their routine sweeps through the premises, to clear out any loiterers before the first rush of spectators was admitted in the forenoon. If only he had remembered exactly where guards were quartered on the site, he could have run straight to them, and endured their jibes for his running from mere boys, though he didn't need to explain how he had Honorius to defend. In service to the father, he wasn't about to risk his son for a fight in which he was vastly outnumbered. Even if he survived, Honorius could be badly hurt, and what then? He would have failed the father. Besides, he had no taste for slaughtering mere street boys, even if they were savage and would try to kill him!

Just to make it doubly sure he wasn't followed, he climbed to the highest gallery, then explained to Honorius what he wanted him to do.

Lancio popped the grate with his foot, which had small iron nails to hold it, centuries old and rusted in their mortar, so they easily released the grate just enough so he could pull it away and not let it fall to the pavement, alerting any wolf boy scout below that they were in the gallery.

With the grate out of the way, Honorius could squeeze out. He wanted to crawl head first, but Lancio wouldn't let him. "Better you don't look down, even if it is too dark to to see much just yet," he said. "Just hold to the side and that will keep you."

Honorius wriggled out feet first, and with difficulty found the ledge and crouched on it, his hand gripped hard by Lancio.

When Honorius got his breath and settled down, Lancio assured him, whispering, "Good job! Just remain there, and if we are discovered, they will see just me, and I will do what I told you I would do. But you must hold to the window frame, and that will keep you safe until it is safe for you to climb back in. Wait until it is light. Then return to your father, with or without me! I told Gais to follow us, but he may not have kept up, or he doesn't care come up here and give our whereabouts away, so you will have to get home alone somehow with your bad foot. Can you do that?"

His stomach churned, he was freezing cold, yet feverish at the same time, and then he retched up his last meal, for the smell of the boys' urine on his clothes had sickened him. When the last of it left his mouth, spilling on the side of the Coliseum, he couldn't use his hand that gripped the ledge, so he had to wipe his face on his own urine-soaked shoulder. He would have loved to wash his mouth out from the awful taste of his own vomit, but he couldn't. He had to endure it, but spit a couple times, and that helped a little.

"If I had only stayed in my bed!" he had time to think, wondering if Lancio had heard him spewing his stomach. He could have spared himself all this misery and trouble! What was going to happen next? Would they escape safely? He had no idea, and despite Lancio's assurances it seemed there was little hope for them. Suddenly, Lancio released his hand, and manfully trying not to cry out, Honorius grabbed the edge of the window frame and held on for dear life.

"Lancio?" he called as loud as he dared, but Lancio did not answer.

Honorius was petrified. Had the wild boys reached their perch? Was Lancio being chased? He knew Lancio could easily kill them, but he didn't because he was a Christian, so he let them chase him instead to hopefully wear them down. It was too dark, and he couldn't tell what was going on. That was the worst thing about it all--not knowing!

"Honorius!"

"Yes!" Honorius almost screamed in shock.

"They're coming up here, so I am leaving you to play fox and hounds. Do as I told you. You will be all right here. Don't move until it is light. Be a good soldier and obey! Then you will see your father and your mother again."

Then silence. Cold, hard silence! And Honorius knew Lancio was gone. He felt sick at heart, and so cold and faint he could hardly hold to the stone ledge--but then he remembered Lancio's words, "Be a good soldier and obey!"

That shamed him, for he knew Lancio was trying to help him, and he stiffened up, and quit crying and settled down to wait, though he wondered what Lancio was doing.

He heard little of what was going on, but there were wolf boy whistles, some shouts, and then a few things flew over the side, which might have been pieces of crumbled masonry.

Knocking at the huge bronze doors, he got a servant to open, and the doors shut again. Knocking again with all his force, he got more servants to come, but they looked at the heap of reeking dirt trying to gain entrance, and didn't recognize him. Instead, they stared and then clapped hands over their noses. But one remembered he had heard a guest say his young son was missing that morning, and in fact many of the servants were already searching the grounds and all the buildings for him. Was this wretched, malodorous person him?

The lady of the house was brought word about the boy at the door, and then his father came from around the side of the house just then making for the entrance. He saw his son and ran up the steps to him, snatched him up, and hugged him so he couldn't breathe.

His father and the lady and the servants were amazed at his terrible condition. He was dirty all over, his face almost black, his clothes torn and unspeakably filthy too, and he was groaning from the pain in his bulging ankle.

"Where were you, son? What happened to you? Did someone take you captive? How is it that Lancio couldn't protect you? Where is Lancio? And Gaius, where is he? They shouldn't have let you go alone like this."

The lady brought them all into the house, sending a servant to fetch the family doctor immediately, and Honorius was given a bench to lie on while the bed was being carried to him.

Honorius was weeping. He couldn't help himself. "I did what he told me to do--wait for the first light, then climb back down from the gallery of the Flavian arena and return here as fast as I could. And I did what he said, but I haven't seen Lancio. I don't know what happened to him."

"But what did you do? Where did you go, so that Lancio was with you. Did he lead you away from here in the dead of night? I cannot believe that!"

"No, Pater, it was my idea. I ran away, when he was guarding my door, and got out a window and climbed over the wall. But some wild boys I ran into thought I was one of them, and took me to their secret place where they keep things they steal from the houses, and--"

"But where is Lancio?" his father interuppted. "Is he in trouble from these boys somehow?"

"Yes, Pater, he may be. Are you going to help him? Please do! It's the Flavian arena--that's where we were, hiding until the wild boys left. He's maybe still there."