V O L U M E

I I

UNCHRONICLE OF THE LAST SHIP TO MASSILIA, PARTS I AND II

A N N O

S T E L L I

402-407

Prophecy by Anchises to his son Aeneas:

"Others, belike,w ith happier grace

From bronze or stone shall call the face,

Plead doubtful causes, map the skies,

and tell when planets set or rise;

But, Roman, thou, do thou control

The nations far and wide;

By this thy genius--to impose

The rule of peace on vanquished foes,

Show pity tothe humbled soul,k

And crush the sons of pride."

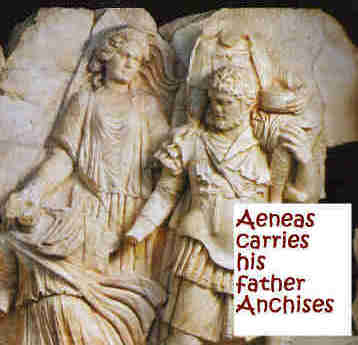

What price epic glory? Aeneas, legendary Founder of Roma, flees burning Troy with his wife and child, carrying his aged father Anchises. The Roman poet Virgilius immortalized him in his epic verses, the Aeneid, but Virgilius's name will be dust someday, whereas Troy will not be, and Aeneas will not be, as there is something more enduring, more lasting, in a brave man's heroic fight to save his doomed city and country and family than there is in the a victor's circle where kings and their allies celebrate their arms and military triumph.

World Empires, like books, have a beginning and an end. The Classical Grecian-Roman World had a Terminus, in fact, two, or Termini, one at the end of the Mediterranean and the province of Britannica at Hadrian's Wall, the other set up by Hadrian at the mouth of the Euphrates River. But the most telling Terminus was the collapse of Roma in the West, climaxed by the actual Fall of Roma to the barbarians who sacked it in 410, only a few years away from the tour of Rufus Quartus Urbanus and his rather conceited, uppity young son, Honorius.

The final collapse took a long time, extending over a hundred or more years. But the signs were everywhere that the whole civilization of the Ancient World was at last unravelling and coming to an end, at last in the Western empire.

Atlantis also had a Terminus, though like Roma its death throes were extended and it took a long time dying. She too had seemed too mighty too ever fall, just like the Roman Empire 10,000 years afterwards. But might and power could not save it. Yet it cast some fatal seeds as it gave up life. Though effectively destroyed except for a wandering, fractured, Topaz-bedeviled colony that could never find a lasting home away from home, Atlantis must have left shreds of its soul behind, which is the only explanation for the Roma's spectacular rise to a superpower and world state from its inauspicious beginnings as a cow town at a ford on the Tiber River. Once it achieved greatness and an empire, it became painfully clear that parvenu Roma needed something to cover up its rather smelly, brutish origins, so the best poets and historians were put to the task. The state annalist, Livy, did his best, tying together the threads of musty, rather dubious myths like Romulus and Remus, the orphaned twins, suckling a she-wolf until they were grown and later fighting it out, the wolf milk perhaps activating their rivalry, and Romulus slaying his brother and becoming the founder of Roma. A city founded on bloody fratricide, two brothers who duked it out for the honor? A city that produced Caracalla, who slew his brother Geta, prince born in the purple like himself, so that he could be Emperor instead of his brother? Virgil the poet did a little better in order to attribute glory to Caesar Augustus's throne, person, and reign. A queen city needs a royal or at least a noble ancestor, so he wrote the great verse epic, the Aeneid, connecting Roma's founding with with Prince Aeneas, the noble son of Anchises who had fought for Priam the last king of Troy (Ilios), thus borrowing from the Greeks some of their illustrious past to gild over Roma's humble cow yard and river crossing antecedents. Aeneas, according to the narrative Virgil adapted for his epic, fled from sacked Troy with his father, wife, and little son Ascanius and sailing by way of Carthage (and Queen Dido's loving arms) reached Lavinium, and became the ancestor of Roma's founders. He visited his father Anchises, since passed away, by going with the Sibyl into the Underworld, carrying a golden branch from a sacred oak tree for his admission to Hades. When they found him in the Elysian Fields, the beautiful part of Hades, Anchises told his son of the greatness of the race that would spring from Aeneas, and told of various rulers to come.

None but simple-minded people seriously believed these fanciful accounts, but in the clever hands of Livy and Virgil they gained a certain degree of plausibility, and Augustus sanctioned Virgil's epic, did he not? What did he have to lose thereby? And the Romulus and Remus story seemed to explain the city's name. So these legends stuck fast, some 700 years they reckoned since their founding date, and Roma now thought it possessed a proper and respectable foundation to explain its phenomenal rise to glory and power over all the other nations.

Atlantean soul-shreds never quite left Italia, even if Roma could not monopolize them forever. Other cities in Italia took them up and were catapulted to glory and power--Venetia, Florentia, even Ragusa on the eastern Adriatic and Illyrian coast chief among them, ruling with the scepter and authority and noblesse oblige of ancient Roma. Even at the time of Rutilius in the early 5th century, Roma had first sunk to being one of two capitals in the realm, Constantine's City, New Roma, claiming preeminence. And in Italia itself, Roma could no longer claim to be the capital of the Western Empire at least, for the imperial capital and court had moved to the safer venue of Ravenna near the northeastern coast. Yet for the old and great Roman nobility, there could be no true replacement for Roma--for it continued to represent, if not embody, all the things they honored and held dearer than life itself.

"All the world's people," said a poet, "are entwined under a single name--Romans. They are world citizens who share a common law. All are Roman citizens who share a common law. All are Roman citizens, peers in their world. They are Roman citizens whether they live in Africa or in Hither Asia or if they live on the banks of the Rhine River. All look to Roma. There is a single coinage. There is a single law. There are no frontiers. No major customs barriers or passports or IDs. Travel is open and free. On the Roman roads, police guard against highwaymen, bandits, and raiding barbarians, keeping guard from guard posts, going on mounted patrols, cruising warships on the rivers and seas, lighthouses and watchtowers, forts, fortified border walls with barracks for soldiers, and for the convenience and comfort of travelers, inns, taverns, and halting stations are open to all."

And a Greek poet was just as admiring, for he said, "In every deed, Roma has made real Homer's dictim--that earth is the property of all. You, Roma, have measured the whole world. You have spanned the rivers with bridges...tunneled through mountains to make level roads. You have filled desolate places with farms and made life easier by seeing that two things are supplied: law and order. Everywhere, O Roma, you have erected temples, gateways, schools, factories, aqueducts, fountains, and gymnasiums. It could be said in truth that the world which from the beginning has been working under an illness has now been put in the way of health...Cities are radiant in their splendor and their grace, and the whole world is as trim as a garden..."

Yes, the world owed Roma all this! It was true that other cities had impressive Roman amphitheatres (such as in Leptis Magna, Sarepta, Hippo, the Tripolitarian cities of Cyrene, Carthage, and others of like splendor on the north African coast) which were almost as big as Roma's, and cities with luxurious baths, aqueducts, and bridges, and culverted, curbed stone-faced roads that fully urbanized the most farflung provinces, but Roma remained the mother city that had given birth to all these wonders. City of the Imperial Topaz, the star-stone of fratracidal conflict, Roma, somehow infused and energized with the soul of lost Atlantis, created a world like unto none other, until, that is, it tore itself apart and the savage hordes of barbarians flooded in to take the spoils.

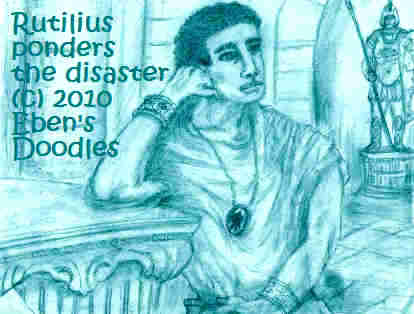

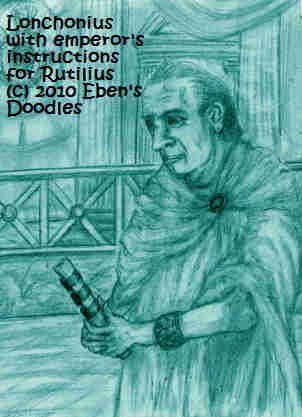

Somehow, as it often happens on board a crowded ship heading to Massilia, word was passed that Rutilius Claudius Numantianus, son of a governor and imperial treasurer of the Capital, a governor himself of the capital and secretary of state, was aboard. Not only bearing these great distinctions, he was working on an important poem. Just as he feared might happen once his work in progress became known, someone came inquiring about it. But he wasn't just a nobody, a commoner. His name was Rufus Quartus Urbanus, and he was a civilized Briton come to tour the grandeur of Italia with his son, and made him the request that he declaim a portion of it to his son and his young friend for the cultivating effect that would have on their tender, unformed minds.

Rutilius was first inclined to turn the provincial Briton flatly down, and even use rather curt words to do so. Son of an imperial capital governor and imperial treasurer, Rutilius was far too noble in blood and had far too much on his busy mind to be concerned about than to take the time to read his work in progress to common people in transit, and thought it might be unsuitable a topic, an elegaic poem on Roma's Decline, to introduce to two mere boys. But the father of one of the boys, a civilized Briton, proved so gentlemanly in his request, insisting that it would educate the boys to the greatness of Roma, that he could not politely refuse. So when the ship touched at Zaelia Magnia, beyond Ostia and Pisa the first port city that possessed a decent enough forum for proclamations, speeches, and official business of state, he spoke to the captain, detaining the ship there. He proved willing enough as they needed more supplies, which had been short in certain necessary items at Ostia, their port of embarkation.

Thinking that he could do worse further up the coast where the barbarians had spread havoc and sacked cities, Rutilius went ashore with his bodyguards and the boys, followed by the father and his two bodyguards. While the father went to see about the pepper business in the spice market (such as it was there), the bodyguards stood watch, seeing to it that no ruffians disturbed them by asking for money or trying to sell something. Rutilius planned to and read them some of his elegy, his swanson for Roma, amidst a proper setting-- the cramped, wooden, somewhat smelly and ratty old grain trade ship being no sort of place for such a reading!

As he looked for just the right place to stand and do his reading, he grew vaguely aware of the rather decayed atmosphere that hung about Zaelia Magnia. No doubt it had been a very thriving place until just lately, he could tell from the size and decoration of the buildings, many of them which were more elegant than most provincial cities could boast. But the markets he could see at a glance were sparse of both shops and patrons even though it should be a busy marketday, with country people crowding in from the farms and villages round about. It didn't help the looks either--those long, sagging lines of graying laundry strung apartment house to apartment house, left there by panicky people who had abandoned the city and fled south with whatever household goods they could cram into wagons. A woman nearby was holding her fussing, colicky baby. What was she doing there, waiting for someone to come and take her south too? She was squatting indecorously at the base of a statue of Flavius Stilicho, imperial commander-in-chief and would-be emperor he resented more than any other Roman general, since, half Lugian, half Roman that he was in blood, since he was fathered by a Lugian with a Roman patrician lady. That Lugian half gave him too much a tie with the barbarians! He had let far too many coarse, evil-smelling Goths and Lugians into Roman lands, Alaric the Goth being the most dangerous of the lot, to serve him or at least be his allies against the most noble Roman families, most of whom could never accept him as Emperor however brilliantly he campaigned with the army, crushing one barbarian horde after another that threatened Italia and Roma.

Statue of Stilicho nothwithstanding, this city would have to do, as he saw no barbarians had gone through here as yet, and there remained at least the appearance that Imperial Roma was in charge and would always be. With Italia's roads in turmoil and a chaos of brigands and refugees and far too few police, and whole areas of the provinces in the north overrun by barbarians, he had to be satisfied with that much--and ignore the woman and child as best he could!

Realizing he couldn't hold the boys' attention for very long, he selected only about a dozen of so lines that he thought best captured the noble spirit of Roma and what she had achieved, and then he chose a spot and stood proudly like a speaker in the Senate giving a speech, his head and shoulders thrown back and his feet firmly planted.

"O Roma!

Listen, fairest queen in all the world.

You are welcomed among the stars of heaven, mother of men

And mother of the gods.

to you we sing praise

And ever shall.

So long as the fates allow,

None can be wholly forgetful of you. Your works

Spread wide as the rays of the sun where curving ocean

Surrounds the world.

Africa has not set you back, with its scorching sands,

Nor the northern climes repulsed you, with its cold;

As far as living nature has stretched toward the poles

So far has earth

Proved accessible to your valor.

You have, O Roma, given the world

A single fatherland;

Even the unjust have found it profitable

To be taken under your dominion.

By offering the vanquished partnership in your own laws

You have made a city

Of once was once the world..."

He thought they looked a bit disappointed with his verses, and he was right. It really was unsuitable, and the boys were far too young and uncultivated to appreciate fine sentiments.

"You think it too dull a subject for boys of your age, is that it?" he asked them, somewhat annoyed at them for wasting his valuable time. "Well, then, what other things do you want to hear me tell about? We might as well not waste our outing."

The youngest boy, Honorius Ubanus as his father introduced him, who proved the brightest witted of the pair despite being a Briton with an accent, spoke up.

"Sir, that was good, very good. But do you have anything more, about the orphans Romulus and Remus and the she-wolf their adopted mother? We'd love to hear about them if we could. We don't want you to quit now."

"But that story is just old wives' tales and nonsense, everybody knows that!" Rutilius scoffed, not accepting the Honorius's clumsy flattery. The boys' faces sank, so he quickly added, "But I have something far better. I have just recently returned from a trip of inspection and private research to the imperial libraries and archives in Roma, and I turned up some things you might find most curious..."

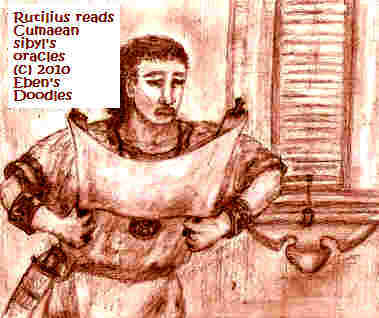

He didn't tell them how bitterly disappointed he was there on his latest visit. He had gone specifically to research the Sibylline oracles concerning Roma's destiny and fate--which he knew they spoke specifically about in a number of highly controversial oracles.

The Archives, he found on arrival, were in an uproar. Distraught librarians rushed to tell him everything. He learned that Flavius Stilicho, just the day before, had sent troops, Roman-armored Lugian and Gothic barbarians, and confiscated all the Sibylline Oracles and had them burnt in big piles below the Capitoline Hill. The loss was irreparable. The votaresses of Apollo had no other copies but these, put in the Imperials for safe-keeping in perpetuum. They were state property and no one was supposed to remove them or tamper with them in anyway, on pain of death. No commander, no emperor, no Senate decree, could overturn the ancient rules governing them. If death was not enough, the miscreants incurred the wrath of the gods, afflicted by a thousand curses all carved in stone on a wall of the Archives. But Stilicho scorned the decree and its punishments. Now they were ashes! The visions and prophecies of the Sibyl were gone forever, like the smoke of the incense that wafted up into the rafters above the tall Corinthian pillars! The priests who attended the holy books had tried to stop the desecrators, even at the cost of being slain if that was their fate. But they were dragged aside and some even beaten who blocked the door to the collection, which was the chief treasure of Roma.

This was the greatest outrage ever witnessed there, indeed, since the time of the first Gothic invasion and capture of Roma centuries before the imperial era. Why had he committed this wanton act of destruction of Roma's most valuable, sacred records and relics? Some said the ecstatic prophecies of the Cumaean Sibyl spoke too pointedly of events and even particular persons in his own barbarian-infested administration. Hearing some quotations from the Sibyl was enough to frighten and enrage Stilicho, whose position in Roma among the best families was already tenuous, so he struck at the Archives and wiped out any suggestion he was a monster tearing down the realm by deferring to barbarians over the safety and welfare of Roma. How dare a priestess of Apollo of bygone days name him and his men? He silenced her voice forever.

Deprived so brutally of this primary source, Rutilius had no choice but to consult secondary, non-Roman sources for whatever visions and prophecies he might find, in hopes of finding enough material to write the destiny and future what he sought. Thank the gods, there were plenty secondary sources that the barbarian-spawned Stilicho didn't bother to molest!

The great Historian of Roma, Tacitus, another historian of note, Livy, and Pliny the Younger, and Suetonius, not to mention Thallus, Phlegon, and Lucius, and, last but not least, Flavius Josephus--all mentioned the crucifixion. They weren't Christians and had no bias toward Christians. Some were quite hostile to Christianity in fact. Wouldn't that be ample proof there was a crucifixion of Christus? Lucien the Greek historian told of the death of Jesus, writing, "The Christians continue to worship this great man who was crucified in Palestine because he brought a new religion to the world."

He of course could find their writings voluminously collected in the Archives.

And then this Jew who was a general in the Jewish rebellion yet cast himself on the Roma's mercy in the campaigns of Vespasian and Titus against the revolt, wrote concerning Pilatus Pontius's procuratorship in Judea, "Now, there was about this time Jesus, a wise man, if it be lawful to call him a man, for he was a doer of wonderful works--a teacher of such men as receive the truth with pleasure. He drew over to him both many of the Jews, and many of the Gentiles. He was the Christ; and when Pilatus, at the suggestion of the principal men amongst us, had condemned him to the cross, those that loved him at the first did not forsake him, for he appeared to them alive again the third day, as the divine prophets had foretold these and ten thousand other wonderful things oncerning him; and the tribe of Christians, so named from him, are not extinct at this day."

And, being a former capital governor and secretary of state as well, he also was free to consult the whole mass of the the Imperial State Annals which included the recorded Senate proceedings, speeches, and acts along with the imperial edicts for the last six hundred years in great detail. There was no duller reading than the records of the Senate, it was commonly believed. But who had ever taken the time to really find out if that was true? Few, indeed! Having thought these would be mainly tedious, business-like accounts as others had characterized them, he found their view was mistaken.

Despite his grief over the burning of the Sibylline oracles, his readings of the imperial and Senate records turned up many curious things about Jesus the Messiah of the Jews.

He could tell the boys about them, too, for some of the Annals described gods that visited Roma in its earliest days, gods that came in flying ships all the way from the stars, it was reported. They used, not sails for propulsion, but powerful crystals that produced far greater speed. Were they Jupiter and the gods of Olympus? They did not call Olympus their home, rather they had a name for it the Greek philosopher Plato had also used: "Atlantis." Wasn't that a lost continent, a motherland of civilization, that had sunk and been utterly destroyed in ages past? Yet if these divine beings had come from there, it couldn't all have been destroyed. Where could he find more light on these beings and their powerful crystals? he wondered, and so he had plunged further into the Annals of Roma, exploring the earliest ones in tier after tier, climbing up and down the gilded ladders to obtain the ancient scrolls, as well as searching the ones written around the time of the gods last appearing, in the reign of Tiberius. That was the same reign when the Jewish claimant-king called the Christos challenged Roma's authority to Jerusalem and all Judaea, and for that he was crucified by the procurator, Pilatus Pontius, only to be found missing from his tomb, which his followers explained was evidence that he had risen from the dead!

Of course, the emperor, receiving the reports of this, was greatly disturbed (and Herod and the Jewish authorities too). Pilatus was recalled, for he had made such a mess of things, he couldn't be endured. He was sent off to Gaul, exiled, but satisfied everybody by committing suicide like a dutiful Roman should who has outlived his usefulness.

But all that was of no interest to mere boys, of course. Once he mentioned the flying boats from the stars, leaving that subject and continuing on to the reign of Tiberius where Christos was crucified, he could see the boys were growing glassy-eyed. So he turned back to the star ships of the Titans, for such the gods clearly were, not the Olympians after all. They said they, not the Olympians named to them, were ruling the earth, or had resided upon and ruled it once upon a time. As for Jupiter and his court, they said they had been overthrown as usurpers, and they were the rightful holders of the throne and its powers. The boys then hung on his words as he told them all about the various things the Titans did while visiting the earth in Tiberius's reign, and saw the boys' mouths hang open breathlessly, so he was very much amused. Their little outing from the tedium of the ship was proving worth the effort after all!

"Did you learn where the gods went after they departed from here, sir?" Honorius asked, as if he sensed that Rutilius had more to offer. "Where is it they live if it isn't Mt. Olympus?"

Yes, he had learned that too, in fact. But he hardly cared about the Titans now, as this had happened long ago, and it was the Christ and his crucifixion and his reputed resurrection that stuck in his mind, and which he could not get rid of. How could he communicate these things to mere boys? They were too private, he felt, as they touched upon certain questions of the soul and its destiny in the after-life, if there was was, that is. This matter of Christos rising from the dead reputedly--even Tiberius believed he had risen after it was reported, meticulously, to him! It was incredible but true, for he had it in the Emperor's own recorded statements and diary. Well, then he was forced to settle in his own mind whether such a thing could really happen. For then it would change absolutely everything! And if this preposterous Jesus of Nazareth was truly what he claimed to be--Son of God, ONLY SON OF GOD, that is, displacing all the Caesars who claimed the same thing--and truly rose from the dead, well, the whole world was turned upside down!

Everything else was mere information: Did Christos really work the stupendous miracles--healing lepers, giving sight to the blind, even raising dead people back to life--that were claimed? Every authority of note in the case attested to their validity. Even his chief enemies--the religious leaders of his own people--accepted these miracles as true events. Nobody had any grounds for questioning them, nor could they, as they were all done so publicly, and countless people were living at the time who witnessed them and were available to attest to them to everybody who asked in courts of law--and did, in fact, ask. So it wasn't the miracles that were germaine to his investigation, it had to be the "Resurrection," which was what the Jews called it.

Nevertheless, Rutilius did speak a bit about the miracles performed by the Christos in Judaea and elsewhere, while avoiding his own feelings and soul-searchings on the subject. His own religion, believing in the gods of Roma, was notoriously sparse in miracle-working gods who walked among men as the Christos was reported to do. He couldn't help that or change that, and so he felt it was best left without discussion. But Honorius, fortunately, was not asking about the gods of Roma and their behavior, which was rather morally questionable, to say the least. Honorius seemed to be just as interested in the details he gave them about the records dealing with Christos' life and miracles.

But then Honorius, like any boy who is too frank with his elders, asked him with childish candor, striking at the heart of the matter: "Don't you believe he rose from the grave, sir? Everybody knows he was crucified, so he had to have died, not just stepped off the stake, and nobody could do that after what they did to him. And then it had to be a real rising from the dead, or all those witnesses were liars and everybody at the time would have said so and hauled them into court and had them punished, right?"

The boy from the provinces was bright for his age, indeed! Perhaps, too bright! thought Rutilius. He hadn't encountered such probing and highly personal questions from noble Roman youth twice his age!

Yet in other respects, he was quite ordinary, being fascinated with the the exciting tale from the Annals of Roma concerning the gods' visit to Roma in ships that could streak through the sky fast as thunderbolt. So he sought to divert him if he could.

When he exhausted this information, however, the boy abruptly shifted back to Christos. Rutilius found himself forced up against a wall by this question, and he actually began to sweat! Again, Honorius put his question to him. "Don't you believe, sir, that Christos rose from the grave? That would change a lot of things in the world, wouldn't it?"

Since he couldn't put the boy off this particular sticking point, he ended the session abruptly and offered to draw the gods' flying ship if he could find a piece of parchment.

Honorius was excited, and so was his friend, and said no more about Christos. So Rutilius, heaving a sigh of relief, looked round for a source of parchment or writing paper, and found a shop selling books. Only the owner had recently pulled out of the business, leaving the door ajar, without even a lock to keep thieves from ransacking what was left inside.

They went in and found the racks virtually empty of books, and yet there were a few old discards, with some pages in them he might use for the purpose. One was a detailed account of the banquets of Nero and Elagabulus, listed with all their enormous menus and recipes! What senseless, vulgar extravagance! One banquet listed a meal started off with the appetizer, 400 brains of nightengales in a mint sauce with contained peas coated with gold! Then there were so many roses cascading upon the guests, that four guests actually suffocated.

Yet another was a poetical work by Commodus, the poetaster and degenerate son of Marcus Aurelius the Philosopher-emperor, praising himself as a god in the most fatuous way. Rutilius dropped this book into a litter of trash on the floor, which it deserved--as this emperor was the cause of the decline of the empire beyond any other bad ruler they had had.

He had read Dio Cassius who had written, "Commodus was a greater plague to the Romans than any pestilence or crime. He wanted to change the name of Roma and call it 'Commodiana' after himself. Melting down a considerable portion of the Jewish Temple of Jerusalem's gold (gold from the sacred utensils) seized as spoils of war by Titus in 79 AD, a statue of gold weighing a thousand pounds representing himself in combat with a bull was cast. He entered the arena to fight gladiators; he was armed with a sword and they only with a woman's wooden weaving batten. He surpassed all others in lust, greed, and cruelty; he kept faith with no one."

And, Rutilius thought, monstrous Commodus met a fitting end. A wrestler whom he had wounded throttled him in his bath!

Finding a more suitable book, that dealt with agrarian matters, he spread it upon the table, found an open space and with a piece of charcoal Honorius picked up in the adjoining room, used to make a warming fire in a brazier, Rutilius sketched the flying ship.

"How does it fly?" "What is its power to fly, sir?" How fast does it go through the sky?" "How did they make it?" "How many gods can ride it at one time?" "Is this the only sky-carriage they have, or do more of them?" "They look like saucers, sir, only they are flying saucers! Do they fight barbarians with these flying saucers?" "Could we ask them to loan us one to fight the barbarians and drive them back to their dens?"

Honorius was literally brimming over with questions, while his friend stood by with wide eyes like a dolt, and Rutilius tried to answer Honorius as best he could, based on his readings of the Annals dealing with the subject. When he finished, he signed his modest effort and handed the entire book to Honorius, who seemed overwhelmed that he should be given it as he stood gazing at it.

Pleased that he had given the boys such a good outing so far, Rutilius next bought the boys each a bag of nice sweet candy. They were fortunate the candy maker was still in town.

While boys were enjoying their marzipan cakes from a Syrian confectioner, Rutilius left the bodyguards to watch over the boys. The captain had still not sent anyone to call them to board, so he knew he had time to look around a bit more, and so he looked in at a jeweler's, Terencio's by name.

He was examining some topazes from India's largest island set like a glistening p;earl on the southern tip of the great subcontinent that Roman traders favored so much for its gold, jewels, and spices. Very large and gleaming like lion's eyes, he couldn't resist making an offer for them. He had lately seen the best jewels that Roma's jewelers had to offer, but these surpassed them.

"What arrangements can I make with you if I should be interested in these four?" he asked, keeping his voice devoid of the excitement he felt.

The jeweler was busy with his wife, son, and daughter were packing dozens of valuable things away into cloth-lined boxes and big wicker baskets, and he turned to the patrician, bowing.

"For you, sir, since we need to dispose of everything we can now, any setting you prefer--for only the price of the jem." "Oh, how about a man's ring in white gold, then a matching one in red gold, and the third can be set as the ornament with ebony on a nice gold chain of small links only for a lady's neck, and I wish the fourth to go in a setting of sapphires in gold for a man's fibula. Is that too much to ask?"

Terencio bowed even lower. "Certainly not! I have all I need to do it. My craftsman is the finest who handles the settings. But there is the matter of the, er, payment, sir."

Rutilius started off with a ridiculously low amount.

The jeweler did not even flinch, much less laugh. "Excellent! They are yours, sir! Can you wait for them, they will be ready in a few days, or should I have them sent by special courier to your residence? Where might that be, sir, for I perceive by your speech you are not from this city and are travelling?"

Rutilius told the man who he was, that he was a native of southern Gaul, and there was the problem that, as he was in transit, traveling by ship because the roads were overrun by barbarians, a courier would not be good enough, he would be captured and robbed on the way.

"So to make sure I receive the full consignment of jewelry I am paying for," he told Terencio, "I will gave instructions to a tabellarius escorted by an armed guard that I will send to your shop for the jewelry, and only then will the full payment be turned over. They will be sent to you by ship, so there will be no problem of being accosted on the roads. Agreed?"

This being said, and agreed to by Terencio, Rutilius was still so amazed by the low price he was paying, he had to inquire, even at the risk of the price being raised.

"How is it that so fine a set can be, ah, so modest in price? I have seen what Roma and Ravenna have to offer, and these are just as good, indeed, they surpass the capital's, and yet you ask less. How can that be? Are they truly genuine? I won't be fooled by glass fakes, either for that matter, for I will have them inspected if I have the slightest suspicion about them, and you will have to bear the consequences of defrauding a public official."

Terencio smiled and scraped, fervently assuring Rutilius that the jewels were all they appeared to be. "My reputation is a most established, excellent one, ask anyone around here, as my family has sold fine jewels and jewelry for generations, and I am only leaving..."

"Leaving?" Rutilius interrupted, his tone growing icy cold. "What do you mean by that? Have you given leave of your senses, man? Here you not just agreed to set the stones and to await payment, yet you speak of leaving? What is this all about, shopkeeper? You know the laws of Diocletian are still binding, those concerning your guild, do you not? Surely, you aren't considering fleeing into the mountains and joining vagabonds and robbers? I am empowered to arrest fugitives, and confiscate their possessions too. Surely, you aren't considering leaving your lawful work?"

The shopkeeper paled, bowing, and his brow and cheeks glistened with visible moisture.

"Yes, indeed, sir, I know the sacred laws, but I paid highly for my official permit of release from the Consul in Mediolanum for health reasons, which you can examine if you like. My health has been most badly affected, my bowels are slack, as I worry myself sick day and night how I--and though I love my country as much as anybody I can't afford to remain here a moment longer than I must, since the trade is so greatly diminished in these parts since..."

Rutilius sighed. "But what about our agreement? Aren't you going to honor it, or not?" "Yes, sir! I plan to send my wife and family and goods on ahead, with protection of course, and finish the remaining business I have here, selling the shop and house and several vineyards and a tabernae I have too if I can find buyers, and surely that will take several weeks. You will be able to contact me in that time, will you not?"

"Of course! If not, you shall know I have contacts, so just leave your address and I shall find you and pay you everything you are owed, and we shall conclude the business satisfactorily."

Then they returned to the subject that weighed heavily on both their minds.

"Oh, the barbarians, the barbarians!" sighed Rutilius, shaking his head. "All these odious tribes of unwashed, greedy, violence-loving Goths who constantly pour across our borders looking for the gods know what! They are tearing apart the whole realm, thanks to certain parties among us who seek their own interests and gain over Roma's security and are opening the gates everywhere you look!"

"Yes, indeed, they are ruining everything here in the Western Empire!" the jeweller agreed. "Some people claim they come to do honest work we Romans won't dirty our hands to do--but that isn't true, they are taking the jobs we find so rare these days, and our people are left without work, with these barbarians seizing everything for themselves and sending our Roman gold back to their families across the borders! But I hear things continue still very good over in the Eastern Empire, in Alexandria, Antioch, and Constantine's City particularly, and so we will be going over there, probably to Alexandria, since the ships dealing with the rich India trade touch there first on return. We have only to find a ship, for I hear they are few these days and are very expensive to board. The rates and charges for baggage are extortionate, which is why I must reduce my stock drastically. If a captain should inspect my baggage and find so many jewels, he would demand half of it for me to board, and I would have to give it! Yet I plan to open a new and even bigger shop than we have here on the street in Alexandria they call Golden Mile. We will sew the some of our money into our clothes and also buy letters of credit in the banks of Roma and buy new stones in Alexandria when I arrive there, where they will be cheaper too! If you see anything else you like, the price will be most reasonable!"

Rutilius relented, turning more graciously to the bowing, flustered shopkeeper.

"I am sorry to see you have to forsake the Fatherland," Rutilius said, though he no longer thought of this man as a true countryman, since he was running away and not going to deal with the barbarian menace. "What if we all did as this fellow?" Rutilius thought. Yet there was no need to question it, he was going bankrupt in this declining city, no doubt. Best he sell out quickly, even at a loss, and set up new in a better, safer city as far away as he could get from Radagaesus, and now Alaric and his hordes! Who could blame him for wanting to leave as soon as possible, if there really was no future anymore for him and his family and business in that place?

They exchanged some small talk, though the patrician Rutilius was not particularly fond of small talk with inferiors, then Rutilius noticed the two boys had finished their treats and were chasing round Stilicho's statue and making a public spectacle, and he saw it was time to go. His four retainers escorting them, they returned to the ship, and the voyage resumed to southwestern Gaul.

They no sooner returned to the ship then the father of the youngest boy Honorius thanked him for enlightening his son on the greatness of Roma.

Rutilius bowed to the older man. "I tried to do the greatness of Roma honor, sir, and hope it made some lasting impression on the boys."

Rufus Urbanus eyed his son closely, and Honorius had something to say. "What is it, son?" his father said. "We had a great time, pater. He told us some wonderful things, all about Christos and the flying..."

The father turned to Rutilius, brows lifted.

Rutilius groaned inwardly. No, no! he thought. Now he would have to explain everything to the father.

He quickly tried to assure the father that it really wasn't so wild and exciting as all that.

"The boy is overstating what I said to a degree, sir. You see, I was in Roma just before I set sail for our family estates at Nabo Martius, and did research in the State Annals and found some curious things, that is all, which I mentioned to the boys to amuse them if possible after I finished the reading of my poem."

Rufus's brows lifted further. "Oh? What curious things? Could you tell me also? I would be most interested to hear about them.

Since Rutilius did not think this talk between adults would be suitable for boys and they wouldn't understand most of it, he took the older man aside, and they discussed certain matters and questions with him. Since he was dealing with a man of experience and maturity, he could go into much deeper detail when relating what he learned from the Archives about Tiberius and his dealing with Jesus the Nazarene.

Even though Rutilius Claudius Numantianus knew he was dealing with a Christian, and the gentleman had a Christian's perspective on things, there were broad areas where they could talk with mutual understanding, since the two of them were Roman or at least debtors to Roma, its great learning and, philosphy, and its grand heritage. They both deeply cared for Roma's legacy and its welfare and maintenance as the lone civilization standing against the darkness and anarchy of the barbarian world.

Approaching Massilia, with a stiff headwind, the oars had to be used, and then they made slow progress into the harbor. An outbound ship came to their attention before they even saw it clearly. The smell gave it away. A slave ship bound for the marts of Malta and Africa, it carried its cargo of souls in the most foul conditions that no Roman gentleman would have countenanced, but it was something that they could not change--slavery was immemorial, and would always be practiced as long as the strong ruled over the weak and certain men aimed to make a profit in human traffiking. They themselves had many slaves, but always aimed to make their lot as bearable as possible. Roma was built upon slave labor, and it was unthinkable that Roma could exist without their cheap labor.

Honorius was standing by himself and saw the slaveship, and a rain squall caught them just as it was coming in view.

The ship was going no further west, the captain informed Rutilius and the other passengers en route, due to the depredations of the barbarians. They were obliged to find other means to get to Narbo Martius and other points in southern Gaul and in Hispania.

Rutilius went ashore, after giving his last regards to the senator and his wife, who were now transferring to a private ship to take them to the Sardinia and Corsica where they had extensive estates. Forewarned by the captain that the roads were difficult to impassable from Massilia to Narbo Martius his destination, he thought of finding another coastal vessel if possible to avoid the barbarians disrupting the roads. Surely, he thought, Massilia was a big enough port to supply a ship going his way.

He went to the Forum first, where all formal business was conducted, the best place to receive the latest news.

The slave mart was hard by, of course, and his eye was taken by some slaves newly arrived. He had plenty slaves on his estates, but he was always on the lookout for younger ones who were sound of body and mind. These looked good enough for his uses, so he went closer to see if any might prove suitable. He thought he might purchase one or two, if the price seemed fair enough, and take them along with him to his estates, which were always in need of fresh stock of that kind.

His eye fell on three, and then when reading their tituli, his eyes widened with disbelief. They were all three from Narbo Martius-- but that wasn't all. He inquired immediately of the trader, and he said he had gotten them from dealers for the barbarian horde passing through that district.

Feeling somewhat afraid of what he might learn, Rutilius decided to ask the slaves themselves who they were and where they had lived at the time of their capture.

Since he was too exalted to address a slave in the market, Rutilius had the trader act as his intermediary. "Where are you from precisely?" the trader demanded from the first.

"The household of Governor Lonchonius," the youth replied.

"And you?" the trader continued, turning to the bigger fellow. "The cattle yard on the estate of Governor Lonchonius," he replied. "And you?" he finished with the woman. She didn't even raise her head, she was so beaten with her recent experiences. "I served in the household, I was a maid and scullery cook in the house of the Governor," she said.

Rutilius was beside himself. He did not know what to say. These were his slaves, on sale in this public mart! Stolen from the estates of his father and himself! What an outrage!

His mind whirled. He could go get a bailiff and confiscate these "stolen properties" immediately, but that would take some time, with the proper records being filed at the court, etc., and local officials would have to be present to ratify the seizure.

All this bother--and he had so little time if he were to find and hire a vessel to take him the remaining distance to Narbo Martius.

But what would he find once he got there? If his estates had been overrun, weren't the residences and outbuildings all burnt and their valuables all seized and carried off by the barbarians? He had to find out at once.

Too anxious to get the news, which he feared would give him a worse picture than he wished to see, he forgot his manners and dignity and interviewed the slaves directly, something unheard of.

"I will have you lashed if you are lying to me. Again, are you three the property of Lonchonius the Governor of Roma and Ravenna? Say!"

All three declared they were, and the trader grinned, exposing big gaps between his teeth. "They speak the truth, sir, look what fine-bodied slaves they are too--the barbarians were good to let me have them, so they could be restored to you--at a certain fair price of course, for I already paid for them with my good money, sire!"

"Yes, yes! You shall have your money. But I must have what they know first."

He turned back to the slaves. "What about the estates? What do you know happened to them? Are they unharmed?"

The youth shook his head. "They burned everything to the ground, sire."

Rutilius's face took on a sickly hue, like ash from a dead fire. He went over to lean against a pedestal without a statue (knocked down by some barbarian perhaps), and pondered the disasters to his family and fortune.

His father and he had spent millions on the new villa, and it had been years in building, and only was finished in the last few monthsw--only to be sacked, burnt and destroyed!

He felt faint, but he dared not show weakness and forced his knees to bear up, and he kept a dignified expression, concealing his true state of mind. When the worst of the shock had passed, he returned to the business at hand. He gave orders to his attendant to pay the trader for the slaves, then get a writ from the city prefect setting them free, and handed him some money to put in their hands to see them back to wherever they might still have homes and relatives. That was all he could do, as he wouldn't put them on any of his cattle ranches south of Roma, not after what they had experienced. The ranches would work them to death and ruin the woman too beyond description. Then they would frighten the other slaves into running away if they told what had happened up north.

Just as he finished this business with his attendant, his eye alighted on another slave, more fair, a barbarian from the north eastern tribal nations evidently.

He went over to examine the titilus, and he was right--this was a captured Lugi, the worst of the tribes attacking and invading the empire. How did he fall into Roman hands? It hardly mattered, not for him anyway. He was going to the mines in Numidia no doubt for his remaining savage, hellish existence, thrust deep under the ground in hot tunnels to hack at the rock with an ax and shovel up the ore into baskets to be carried by other slaves up to the surface he would never see again. No wonder the slave looked so downcast--he sensed his doom and had lost all hope!

Just then Rutilius felt a surge of feeling for the barbarian savage. Why? He had no reason to feel any such thing. After all, this man and his race were destroying the empire, ransacking and burning his own estates that were the flower of Gallia. He deserved every bit of the hell he was going to experience very soon now after he was bought and transported with a hundred others like him to the Spanish or North African mines. Yet he felt the same powerful feeling he would feel for a brother! He couldn't resist it, though it went against all his Roman instincts, being akin to mercy.

He turned to his attendant.

"Buy him also. But I don't want the beast in my employ! No, free him also, and send him on his way. I don't want to see him ever again!"

He turned away, more disgusted at himself than at the Lugian. How could he treat such an animal with compassion? It was unseemly. Compassion was utterly wasted! He might as well try to tame a brute lion or boar than this creature of violence and destruction!

Rutilius went to a place aside from the busy market where he was a bit more alone, where he tried to clear his mind enough to think clearly what to do next.

With the roads in chaos, with no doubt brigands preying upon all who yet ventured to pass on them, and his estates burnt, what was there worth visiting? His whole trip was jeopardized, including his business arrangement with Terencio the jeweler back at Zaelia Magnia. Perhaps his villas and estates could be rebuilt, but without Roman law and order restored in the region, the effort would be useless. Was Narbo Martius yet another district and city Roma was abandoning to barbarism?

He had to make sure--that it really was as bad as reported. He decided he could find out, not just depend on people's word, but the evidence of his own eyes. The condition of the road, the Via Aurelia, would tell him all he needed to know one way or the other.

He went to hire a conveyance and found all manner of carriages, from raedas and caraccas to sedan chairs. There was a great variety, he found. The proprieter told him that the previous owners were glad to get rid of them, since they were leaving their estates for good and wouldn't need them anymore. Some needed the money too to get away, since they had lost most everything when the barbarians first swept through and burned many of the villas and sacked the towns and cities as well in many parts of Cisalpine Gaul.

But Rutilius did not need anything elaborate, just a means to get to the main road where he could observe the traffic and tell from that what chance he might have of going westward with reasonable safety.

He could marshall a small army and fund it himself if need be, if he gave himself time to apply for troops, that is, for being a former governor of the imperial capitals and secretary of state, and being the son of the famed Lonchonius, he had access to imperial troops and boyguards. But that took time, and he didn't want to wait.

So he hired a simple sedan chair, and the renter provided the slaves to carry him for that day's excursion.

Soon he was on his way out of the city and heading for the main thoroughfare that took the main east-west traffic along the coast, the part of the famed Via Aurelia that led along the coasts of southern Gaul and down into Hispania, all the way to Cartegena on the midpoint of the eastern coast.

Just a few miles out from Massilia he saw what he had feared--the traffic was like a stampede, a chaotic multitude of pedestrians, wagons, carriages, horses, oxens mostly all heading east and south as fast as this motley mob could. His heart sank. How could he make it through such a mass? There was not room on the road to spare, people were filling the ditches as well, and he would be pushing against the tide of humanity that was fleeing the barbarians and heading toward Roma and other southern points of the peninsula where it was thought there was safety and law and order.

Rutilius gave the order for the chair to be set down, and he got out and stood watching the refugees. Every class was represented. Slaves, nobility from patrician to knight, rich and poor-- the entire society of Roman Gaul was in flight! It was the most amazing spectacle. He tried to get someone to pause to give him some news of Narbo Martius and its environs.

But nobody wanted to stop, they only wanted to make it as far away from the northern barbarians as possible in the remaining daylight hours. Who could blame them? The terror the barbarians inspired was plain on all their faces!

Rutilius saw how completely hopeless it was regarding any journey westward. He would need an army to escort him to Narbo Martius and to his various estates--if he wished to return from there alive, that is. He returned to the chair, sat down, his head in his hands. Then he roused himself, and gave the command to return him to the city. There he would write a message and have it carried to Terencio, that he wasn't able to carry out their business arrangement after all, and whatever losses Terencio suffered in the matter, he would recompense him-- should Terencio be able to leave word for him at the Prefect's palace in Roma of his whereabouts. Failing contact that way, Terencio might send word to him from Alexandria on his arrival. In Alexandria he had lines of credit. Upon hearing from Terencio, he would send word to Sarepedon Tranquillius the banker on the Canopic Street to remimburse Terencio. That was the best, the most fair thing he could do, he thought. The Numantianii had always treated tradesmen with punctilious fairness, and took pride in that fact.

Now, with Terencio dealt with, the matter at hand was far more serious. Rutilius had seen what he had come for, and it was more than he could bear to look at any longer. Disintegration had set in too deep to patch over or stop, and the ground was cracking and falling away in huge wedges, all the way toward the heartland of imperial Roma, Latium. Obviously, even with Priscus Attalus as "emperor" sitting on the throne in Ravenna, and the dire Flavius Stilicho, magistum militum and the real emperor in the realm except in title, things would not get any better, no matter how many barbarian armies Stilicho hurled back toward the frontiers or bribed off with the last reserves of the imperial treasury.

What should he do? Where should he go? Return to Roma, or go to Ravenna bearing the bad news to his aged father and kill him with it?

Needing to sleep on it before he made any decision, Rutilius had the porters take him to a villa just outside Massilia in a nice suburb of the wealthy, where a former consul and praetor and a for-life senator, Secundus Sylvanus Fabio, resided. His father being a patrician and peer of Secundus Fabio, both speaking often and well of each other, he knew he would be most welcome even with no prior notice, if the family were in residence, that is, and not seeking rest or recreation at their various other villas in the south of Italia and elsewhere. As for the Urbanii, they would have to chance it if they continued on to Narbo Martius, he thought. He could only send word back by courier and warn them of the real risks, and advise them to seek some other route back to Britannica, by ship, not by land if they could find a ship. As for himself, he couldn't go home. He would send an agent in his place, who wouldn't be so conspicuous as the former governor of the Capital coming in state with bodyguards.

His ancestral home and estate no longer existed, thanks to Stilicho's policies admitting so many of the rapacious Gothic barbarians into his home province--only for them to break treaty and destroy everything in sight like bulls set loose in a pottery shop!

What a harrowing scene he had just witnessed out on the Via Aurelia! It gave him the chills. Carts losing a wheel or the wheel broken from being run too long and hard on the roads, their goods tumbling onto the roadstead, then masses of wagons and people and horses rolling right over the poor owner's possessions, even trampling him as he sought to keep his things from being destroyed!

Shrieking women and even young girls, half-naked, pleading for help while trying to run from pursuing gangs of men--while police and soldiers on the road kept walking by, without going to their aid.

Robberies, too--brazenly carried out, with the police again looking the other way.

Rutilius himself realized he could do nothing for such wretches. He couldn't fix all the things he saw happening around him. No doubt the robberies, the rapes, the many other crimes had happened to hundreds and even thousands, as the stampede continued, drawing tens of thousands of frantic people to the roads, all trying to get out at the same time if they could.

Roma was literally falling apart, piece by piece, before his eyes! he thought. It was an agony for him to witness it.

Pregnant mothers, old grandmothers who could scarcely walk, little children, the infirm and the ill, and the tender young women of well-born, prosperous familes who had never been exposed to hardship and the open road and the stares of rough workingmen and riffraff-- it was a most painful sight to seem all struggling to keep moving. Babies and young children were crying all along the road, the mothers unable to stop and care for their needs. Other children, badly frightened, were also crying. But their cries mixed with the moans of the elderly and the infirm and ill, so that the whole line of humanity was one huge mass crying out in pain and fear.

What was to become of all these people uprooted so violently from their ancestral homes, their livelihoods lost, their cities and their work and trades wrecked--all their associations with place and society destroyed, swept away forever? All they could take away intact was their Roman citizenship, but what was it worth today when so many barbarians could claim to be Romans too (thanks to Stilicho's grants of amnesty to hordes of them in order to gain their support for himself).

Who would find new homes and work for the dispossessed? There weren't homes and work enough whereever they were going. Weren't most of these people staring in the gaunt faces of starvation and abject poverty, no matter where they managed to run to? Their money would run out, what then? Wouldn't all these young girls he saw walking along the road, all so sweet and innocent, daughters who had never known public exposure, be sold by their fathers as slaves for the sex merchants?

The unthinkable would happen to them, all because these families would be reduced to absolute desperation somewhere along the long road to supposed safety in the south.

Their virtue would be violated, their dreams for their lives utterly crushed, so that their families might not starve to death for a little while longer. Perhaps, their sale for prostitution would buy their families fares to Alexandria or Nova Roma, Constantine's City, where they could make a new start possibly? But these young and beautiful girls, which he saw by the hundreds passing by, they would be ruined, and dead in a few years after being sold in the slave marts of Roma, Brundisium, or some other city along Via Appia.

And these elderly and sick-- surely they would perish soon, they would leave their shallow graves by the thousands along the roadsides. And the little children, the babies--many of them too would die in the blazing sun from lack of water and food. Mothers giving birth would not have the strength to carry a baby onwward, and it would be left by the roadside too.

He had not dreamed he would see this catastrophe in his lifetime, as Roma possessed the greatest power and an invincible army and used to have the vast funds to put legions into the field against anybody who dared to defy the empire. But now the state treasury was virtually drained, and so there wasn't the gold and silver to fund the legions or keep them where theyt were stationed to hold the borders against all the barbarians pressing against them. Yes, Roma was never able to match man to man the numbers of barbarians, but it didn't need to. Roma's reputation terrorized the barbarians and that terror kept them out and at bay, until recently that is! When they Goths and other savage tribes heard that Roma's leaders were at last losing their grip, unable to field a legion or more against them, well, they started flooding over the borders in Gallia, Hispania, and Africa--and once the barbarians lost their fear of Roman reprisal, it was all over, even though Stilicho still won battles against them when he could catch a mass of them together organized in an army.

Carried to the Senator Fabio's estate, Rutilius drew up before an imposing but scarcely defended gate, and his credentials were clear enough to two rather careless, scornful Lugian guards, which were of course abominable Goths again hired as mercenaries for such needed posts!--would he ever be able to see Romans or Italians again in such positions? It disgusted him no end that even the Senator saw fit to hire such ruffians, but he thought maybe there were no suitable Italian coherts or even Syrians or Britons available and he had to turn to the huge masses of barbarians who gave Roma so much manpower nowadays.

At the porch entrance, he got down and was escorted by family servants into the hall, and there he waited, and presently word came to him to proceed to his suite of rooms that the wife of the Senator had opened and aired for him. She sent a note, that she would be seeing him as soon as he was refreshed in his quarters, as she had some important things to convey to him, as the Senator was not disposed to admit guests at that time of day, being ill and keeping to his bed.

"Ill?" Rutilius thought, as he was led to his rooms on the second floor. "Was the Senator so indisposed that he couldn't be seen at all? This jeopardized his plans, and perhaps he might have forget about a restful interlude at Fabio's and strike out at once to Ravenna to see his father, without giving him time to send any letters to him, breaking the bad news more gently about their Gallic estates after he had time to compose what he would tell him?

When he had bathed, dressed, and felt much better, he was brought a solid meal served with the best of the estate wines, chilled, and every other possible need was seen to by the household servants. Only then was the Lady Fulvia announced by a lady attendant. He left his chambers and out of respect for her went into the hall to be welcomed by her, and without after nod of her intricately coifed head she turned without a word and led him to a more private chamber to speak to him, in a room she used for a chapel. He understood the reason. She was seeking solace these difficult days in the Christian faith (which he had heard rumor of in Roma), though her husband the Senator was not, being of Rutilius's beliefs about the god--gods were good enough for a thinking man's homage, so long as they refrained from meddling in men's affairs. Besides, like so many Romans, the Senator favored Epictetus the Stoic, and with a touch or two of Epicurus where he was addressing the fitting end to take for the close of a life of pleasure and cultivated refinement.

"Welcome, Governor, to our home, such as it is these days!" she said to him, after taking the chair brought to her. Rutilius was waved to a chair across her, and the servants withdrew so they might talk without distraction.

Lady Fulvia smiled, showing traces of beauty she was renowned for in her youth.

How old was she now? he wondered. The Senator had married her after his first wife's death, and married her at nineteen, thinking perhaps he had better chance of producing an heir with her, having failed with his first wife.

"How is your father, is he well?" she first inquired.

Rutilius told her that he was well enough for his age, and still able to attend to some of his duties at the court and in the capital.

Lady Fulvia continued, this time her look changing from the gracious hostess to one of concern and sadness.

"I am afraid, Rutilius, we cannot provide you with much amusement and diversion here, as Secundus is ill and in great pain for days now at a stretch and must keep to his bed, which he utterly loathes, of course, being so active all his life. That to him is the worst pain, being deprived of his active life and reduced to helplessness!"

"So I have heard, and you have my condolences," Rutilius replied, with as much feeling as he could muster, as he too had an aged parent on his mind to consider, which could not be much different from an aged, ailing spouse to this woman.

Her hand went up to her necklace of pearls and amber, and played with it distractedly, and then she leaned toward him.

"You can reside here as long here as you like, be assured, and we will make it as comfortable for you as we can--in the circumstances."

"Yes, I have heard the region is in turmoil these days," he said. "In fact my familial estates in Narbo Martius--

But the lady seemed not to have heard and continued, cutting him off.

"Servants are running away from here, one or more every day, would you believe? We offered them freedom if they would stay on longer, but it doesn't seem to have helped, they are so frightened of the--"

She broke off, and Rutilius knew what she was reluctant to say, naming the barbarians that were ravaging Gallia east to west, and north to south.

"Yes, I understand," was all Rutilius could say, as sympathetically as he could.

She looked at him with bewilderment, even shock, as if the unspeakable were beating on the very doors of the house.

"This can't be happening! How can it be happening? Why, all our friends from this area have run away--for good! We are about the only ones left, and... well, you see what sorry condition we are in. The whole estate is falling into disrepair. Everything is going to ruin!"

What could Rutilius say to that admission, it was evident that the lady was most distressed by the current state of things. All her life she had lived in luxury, Roman peace and safety, with every need and whim taken care of in a timely fashion by well-trained slaves and servants--but that was all crumbling and vanishing before her eyes. Roman civilization--well-run, with laws enforced, strictly and without fail, and no nonsense mixed in either--was all she knew, and only barbarism was left to take its place, and where could she find a place without Roma? How could this happen to Romans?

Rutilius could not explain the many causes, nor name the chief malefactors, such as Flavius Stilicho, as he knew the Fabios were of a pragmatic group of solid, republican-spirited Romans, both Christians and some holding to Roma's old gods and emperor worship too, that believed in the virtue of sheer expediency in times of emergency, with some of his younger class too, that even with Stilicho's clear ties to Alaric and other Lugians, he was just too good a military commander to be put away right now. He had to disagree past a certain point with the Pragmatists. Principles were important too, even while holding to expediency. Sheer expediency wasn't everything, when dealing with the likes of a Stilicho! That dark horse, however strong and impressive, could provide a most disastrous upset when you least expected or could sustain one. Even with Flavius Stilicho still winning major battles and crushing barbarians wherever he could get them to stand in a massed army he could attack, things were not improving, but rather they were falling apart all the quicker ever since he was given full powers to operate with the remaining resources of the Imperial State military and treasury! Was the trade-off worth it? He, Rutilius, didn't think so!

"Can't you remove from here in the north, Lady Fulvia, if things become too, er, uncertain in this area? You have some villas and estates in Sicilia, I hear, and surely they would be safe and pleasant enough to reside in during the interim."

She seemed to come back to reality with a jolt. Her pride restored her clear Roman thinking. "No, we cannot move--not at this time! We have a raeda of course, several of them, and a cisium if we must go much faster, and some postillians and guards enough to accompany us, but the Senator is far too ill. He could never take the journey. So we must remain here, and try to make the best of it."

Rutilius looked at her with misgiving. How could they put off the inevitable? The barbarians were pressing in all around--soon the villas in the environs of Massilia would be sacked and put to the torch, occupied or not. When they finished with those, they might be emboldened to attack Massilia itself. If the Fabios didn't get out now, wouldn't it be too late at another time? It could be a few weeks, or even days, from the looks of things, before law and order disappeared completely from the region. What then? He himself had to leave the Fabios soon. He was planning to stay only the night and leave in the morning, in fact, so he tried to think of a polite way to say his visit would be unceremoniously brief.

But he did not have a chance to say anything about his leave-taking, as the Lady Fulvia saw a maidservant approaching and took the whispered message.

Lady Fulvia brightened, as she glanced at Rutilius.

"I was hoping for this. The Senator sends word that he is feeling a bit better, and wishes that his guest come to his bedside for a proper welcome. Would you? It would mean much to him, as we receive so few guests these days, it will break up the tedium of his day."

"Of course, I will go with you at once, Madame!" Rutilius smiled, and rose with the lady, and she then went ahead of him, a maidservant holding her arm.

They reached the Senator's sick-chamber at the end of the long corridor, with the rooms facing south to catch the cooling sea breezes when they blew.

He found the Senator lying back on his couch, but his eyes were open and his mind as sharp (and his tongue no less acute) as ever. And that deep, growling voice of a bear of a man, who could forget it once you heard it?

"Come closer, my boy, I won't bite," he growled, sounding very much like he very much wished to. "Let me look at you!" was the Senator's blunt greeting when Rutilius was announced to him.

"Well, Lonchonius could do worse in a son!" was his reaction. "But I've heard you are a bit too fastidious in the affair of love, my boy. You haven't taken a wife or mistress, nor have fathered any offspring to bear the family name and patrimony onwards--what--what--but that's your business, not mine. I did my best, but I still have no son and heir of my own, so I should talk! Now, what do you think? Are we--I mean, Roma--finished, or what? From the looks of things I hear about but don't see any longer, being tied to this confounded couch, those tribes and hordes of unwashed Lugii will soon be here, howling like wolves and hacking off our buttocks and sacking the whole country, including this house of mine, right?

Rutilius couldn't deny it. But he tried to comfort the old, dying man of renown, just to ease his last thoughts a bit. "Well, sire, things may still turn around. We must remember that Roma has faced many strong foes in the past and where are they now? We are still here! A leader always arose in a calamity and victory came, and our dogs lapped our enemies' blood. After all, sore calamities have always confronted us, and often it seemed Roma was finished. Remember the Goths when they sacked Roma, then later Hannibal and Carthago and all those victories of his over the best we put forward, and Pyrrhus and...!"

The old man shook his fist, weakly, but it was clear he was angry. Where he would have roared, he now only growled and sputtered. "Oh, stuff and nonsense! Don't speak such drivel to me, boy! I'm not a schoolboy to be taught such things. This isn't a recitation drill! I won't hear it. My wife--yes, use those patriotic sentiments with her, as women can't bear rough and sensible man's talk. But the world of men, now, there we must speak as true men! Now what do you think we should do? I don't have time to indulge in Greekling sophistries! I don't believe in the gods, everybody worth his salt knows they are nothing but silly little tales told by fools, but I do know there is a time appointed for every mortal man, as I feel mine coming soon, in my very bones! I do not know the day, but I can tell the hour approaches closer with every breath I take!"

Challenged man-to-man like that, even though the other man was so obviously fading, Rutilius had to forget about humoring an old, dying and yet impressively dignified man and decided he had to get down to business. He discussed strategy and possible commanders and resources that still remained, and there as even the exceptional option of calling for help from the Eastern Emperor--massive aid which he knew they were capable of giving along with first-class armies. Western Roman needn't fight alone against all the barbarian hordes. It was unthinkable, that the Eastern Empire would let the Western perish while it watched on the sideline!

After a full hour of intensive strategizing, the Senator had enough and sank back speechless, and his wife came and Rutilius left to return, himself drained and tired, to his rooms for the night.

He sank most gratefully into the damask quilts of his bed, but the night was not a good one for him at all. Shuttered windows shook and banged in a fierce wind blowing up from the south--wind off the vast red and yellow continent, from howling storms of the deserts of Africa, carrying heat and choking red dust and an alien scent and spreading it over half of southern Gaul and Cisalpine Italia.

He couldn't sleep and tossed on his couch for hours. Then, exhausted, he sank into sleep and a dream came. It was so vivid and powerful it was like he was really living it, and it seemed a matter of life and death what he did in it.

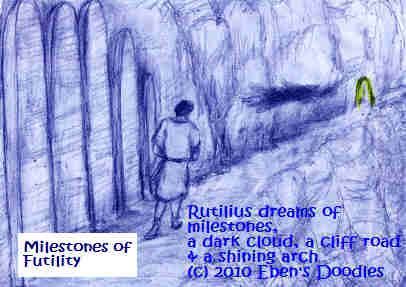

He found himself walking past unfinished stelae, which looked to be either grave markers or milestones, only unfinished. grave markers or milestones, There was a row of them, and the one next to the last carried the present year. Strange stones! They did not remain blank for long though, for as he passed each, letters appeared, and he saw etched on them events too, so he knew the years from some of those events, even if some dates were well before his time and meant nothing to him. But each milestone, or grave marker, seemed to mark some critical juncture in the progress (or decline, it seemed to him) of Roma's fortunes.

The last recording stone was blank. He stared at it, wondering what it might contain if the events were etched there as they were on the others.

"Is this one standing for what will happen? Is this our future? Is this our end? Which is it?

As if in answer, he next saw a cloud appear on the stony path before him. It was a dark little cloud, and then he realized the path was not on level ground but there was a sheer rock wall to the left and a sheer dropoff to the right. He had to go through that cloud if he continued on the path. Truly, there was no turning back for him, for he saw, with a shudder, the ground fall away behind him, leaving an abyss that was seemingly eating the path with each step he took forward!

He moved forward and met the the ugly, dark cloud. The moment it enveloped him, he found himself assailed with every sort of thought and wild fancy. He thought he was going mad. He could not control the assaulting thoughts.

The cloud was full of whirling dark shapes, that seemed to threaten him with huge teeth like knives and swords. He reared back from them, but not too far, mindful of the chasm to his right and the one opening at his back.

"Woe to you, Roman!" he heard a voice greet him in the cloud. "You will rise again, but the Son of the Majesty will arise to strike you down a final time, though you have exalted yourself to the heavens! Your glory he will cast down to the depths and trample upon. You will rise no more, and your oppressions will cease forever in the earth, which my own Great King, not yours, will rule forever and ever! Yet you, son of Lonchonius, I will separate from you people and nation for My own service. You I will cause to write on the last milestone the things I want there. Seek me, and you will be my servant and not perish utterly with your people, nor rise again with the Man of Sin and fight with him against Me and my glory in the latter days."

Rutilius reeled out of the cloud, which retired with its swarm of horrid, flying monsters, but it was that Voice that tormented him most. He "would rise no more"? What did that mean? He hadn't fallen, so how could it mean him? It made no sense to him. And who was this "Son of Majesty" the Voice spoke of? He would be chosen out of his people, the Romans, to be a servant, and write on the last milestone the things the Speaker desired to be there? He would not be raised to fight against the Speaker in the 'latter days'?

The arch and the declarations did not make any more sense to him than the fateful Voice. He found himself walking beneath it, and it was beautiful, but what could it possibly mean, particularly after he had just been told in the cloud of a wretched end for himself, that he would be cast down from his place of eminence and would rise no more, yet would be 'separated out' and used to write on the Terminus Stone?

His experience of the Arch was incomprehensible--what else could it be to hi? After the unpleasant, almost terrifying struggle in the dark cloud, he felt an overwhelming peace coming to him from the Arch, such as he had never experienced before.

This wasn't the Pax of Roma or the Pax of Caesar Augustus--it was utterly different, it was seated deep in his heart and soul. What could it mean?

Crash! He fell abruptly from the dream into reality, and lay in the darkness of his bedchamber, wondering what had happened and wondering for a few moments where he was. Then he heard more sounds, as if glass were breaking outside his door.

He had to find out what was going on, and rose. His bodyguards were in the slave quarters retired for the light, and the moment he opened his door and moved into the hallway, he sorely missed them, for he saw who was making the noise.

A shock-headed Lugian mercenary guard from the gate, wearing only a simple tunic that barely covered his powerful limbs, was grabbing valuable things he wanted from the walls and niches and putting them into a bag, while dropping the unwanted items to smash on the tiled floor.

"Thief, scoundrel, put those things back immediately!" Rutilius commanded the Lugian.

The Lugian saw him, and grunted, as if he were laughing.

He turned back to what he had been doing before, ignoring Rutilius as if he were no more than a buzzing fly.

Angry, Rutilius gave him a second barking command to stop, but the guard this time was annoyed enough to walk right up to Rutilius, staring at him with his cold blue eyes.