After Gabriel’s spinning out of his dreams, what was left? Horace wondered. What was left? He couldn’t go back to Lois Lane, the conventional, suburban, whiteman's life he had lived there. Not without Gabriel!

Like his brothers before him, he could do nothing only so long. He started walking when the weather cleared, and they saw him go out the door, and that was that. They knew they couldn’t stop him this time, so nobody tried.

He headed toward Brule on restless, itching feet. He had been there before at the old mission, the people where he had relatives, so he remembered some things, and the place drew his feet that way.

It was fortunate someone was driving that way, for hours later he was tired, but the wind was too cold for him to cover himself with a blanket and get some rest, and the truck cab, with a heater working, felt pretty good, he had to admit after tramping how many miles?

The bottle passed to him warmed him up even more.

The brother, old Jim Tumble Weed who ran a twenty head herd and did some mining in Montana to make ends meet--since he wasn’t enough Lakota, the B.I.A. said for a monthly check--wasn’t going all the way to Brule, so he had to get out, empties tumbling out with him, but he was a good half way there, Horace figured.

Funny thing, he knew deeper down that he wasn’t going to Brule after all, but it had got his feet moving, and once moving he found his feet weren’t going to turn toward Brule and the Black Robes. No, they were leading him southwest, beyond Brule. How far beyond? He’d just have to find out when he got there.

Things, once he had got going, began falling in line. He could see it, but he didn’t feel any better.

“I can always go drown in a river, or drop down off some high-enough cliff,” he decided, if the pain got any worse.

He was only a cousin. How did Gabriel’s mother, father, and brothers and sisters take it? They didn’t seem to be so shaken up, and going to pull through, he could see. That was all right. Gabriel would want them to.

“But,” he thought, checked by the thought. “But what about Gabriel’s dreams--his chronicles? I’ve got them, and that Wasichu who was taking care of him--he’s got some too, I know. What do I do now? Huh, Gabriel? What do you want me to do with them?”

It helped some to talk to his cousin. He didn’t feel so empty, alone, that way. Ordinarily, brothers were never alone, anyway, not with all the living things, their spirits and the spirits of the air, water, ice, wind, fire, the earth, but a brother was meant to be with his people--they never left you, even when you were out hunting or walking alone. But Gabriel’s death was different. It had taken something away. He didn’t feel his people’s presence, living and passed on. The relatives--like, they too didn’t rise up to comfort him or befriend him as he passed by. To them he sensed he was a stranger, a passing cloud.

He really felt like he was dragging himself beyond the point where he should not have lived. He had come to the end. Why hadn’t he died? His body lived, but his spirit had died inside.

“They took you to our forefathers, brother, why not me too?” he cried out, again and again. No answer ever came back, however.

He kept going until he had to drop and cover himself with his blanket. Whether he slept or not, he didn’t know. So cold, so stiff, he couldn’t stand it after a while, so he got up and stumbled on, hour after hour.

Somehow he got to a river, and the banks gave him shelter he could appreciate. Out of the worst of the wind and cold, he crept along them until he found a hole to crawl into. Inside a crevice, he pulled his blanket tight, and got warm enough to be taken by sleep.

In the morning he crawled out, found himself a foot away from a tumble into a fast-flowing stream forty feet below, and climbed back up to the level ground. Continuing on, he saw a ranch house, and careful of dogs or anyone with suspicious thoughts about a lone Lakota, he made his approach.

He stopped by the corral, then with no dog rushing at him, he continued toward the ramshackle house. Not knowing what ranch hands would do if they saw him, he decided he’d maybe do better with the owner.

A back door banged open with a kick. Horace saw the snout of a sawed off shot gun pointed at him, the same gun no doubt used to send stray, half-starved, cattle-worrying dogs running for their lives. “Keep movin’, boy, back the way you came!” an old man shouted. “I’m not known for missin’ a varmint when I see one sneakin’ on my place.”

Horace, with no desire to test the man’s mettle, backed up just as he was told.

When he thought it safe, just beyond the corral, he crouched and ran like the wind. Behind him he heard a shot, then another, and he kept running.

“Why not let him shoot me?” he thought. Yet he ran.

It was a good thing, running. He felt better, after he stopped when he could run no more so fast, and needed rest.

His feet dragging in the dirt and snow, he walked onward, gasping for each breath.

Tired, famished, cold, he didn’t care anymore. His feet, awakened by the shooting, seemed to have new life and new direction. No longer dragging, they began to move quick.

He followed.

Knowing the trick from having learned it from an uncle, Horace cut across the rabbit’s circle all of a sudden and with his stick gave it a whack as they met.

Fortunately, he had matches for cigarettes still on him. He scooped out enough earth to make a shelter for the fire, and had a fire going after working at it. With the stick and a couple more he could find, he got some rocks heated, and roasted between the rocks.

It wasn’t much meat, but it would keep him alive for another day, he knew, as he tore off the smoked and roasted meat with his teeth.

“Thank you, brother,” he said, as he finished the rabbit.

Feeling better, Horace looked out in all directions. Now where was he? He couldn’t tell by the country, but the mountains to his northwest, that had to be Montana. And the higher mountains, sharp tooth in the crests, had to be the ones in Wyoming--where his feet were leading him.

He started walking again.

Finding another creek, he crawled into a shelter under the bank and slept a second night.

Day after day, rabbit after rabbit, and sometimes a squirrel, he kept himself alive and continued on, gaining on the mountains. Ranches, roads, hostile dogs, hostile Wasichu kids roaring drunk and taking potshots at him as they roared past in trucks--it was the same old story. That’s why he preferred not to go along the roads. He didn’t feel free on them.

Out on the ranges, he had to climb over a fence ever so often, but that was nothing. So when he came to a road, he crossed it like an animal and kept moving on across open country. The weather turned warmer, but when he started climbing, all that warmth quickly left him, and he found snow and ice country all around him, with no way to avoid it.

It was high enough now to be dangerous going. Climbing in snow, he wasn’t good at that, not mountains of it. Used to plains, he didn’t particularly like the heights, especially ones so cold and white. But there was only one way through, going up and up and up until he had crossed whatever mountains were in his path.

What if the night caught him? he had to wonder. There was no shelter, and he would freeze to death. What was one blanket against so much snow and cold?

His blanket wrapped around him, he stumbled and slipped and climbed onwards. It was crazy, it was asking to die, going on, but he knew he would die if he turned around, for then he’d slip and fall into some hole or other, or start an avalanche.

His feet digging in as best they could, his hands clawing into the snow and ice for handholds, he kept on.

He didn’t know anything but climbing in the pure whiteness after a few hours. Time seemed to stand still. Was it day? Night? He climbed, and he climbed.

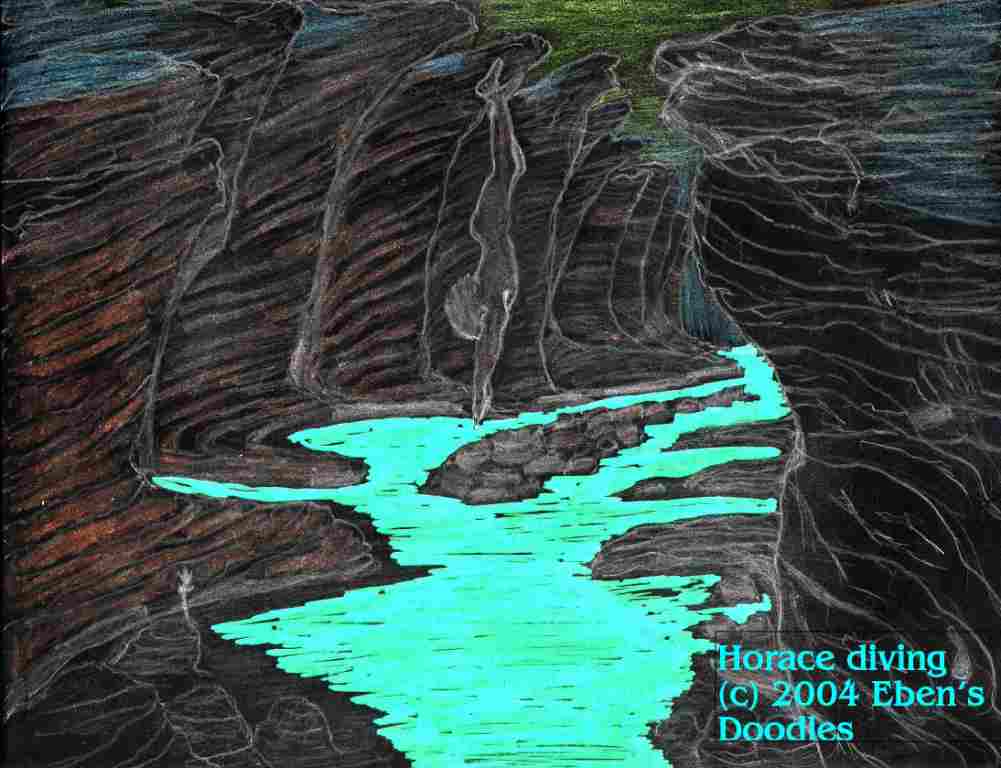

Then he came to a crest and, beyond, nothing. The world fell away sharply. The cliff beneath him stretched thousands of feet downwards into a vast bowl in which a million Horaces could fall and nobody would find them, it seemed.

“What am I going to do?” he thought. “I can’t climb down this--it’s all ice and snow.”

He had come to the end. And there was no going back down the way he came.

The wind was so strong and cold he was freezing to death.

His blanket had eagle feathers woven into it. Why not just spread his “wings” and dive off? Why not? He had nothing, even on Rosebud. The people were all dying, the Sacred Hoop lying in pieces round their ankles.

Whatever it was, youth, the will to live, the realization he had not reached his destiny, the speaking Wind’s words, Horace, challenged, did not spread his blanket out and dive. Instead, he followed the crest, and, indeed, it climbed higher. He left the cliff edge gradually, and the mountain broadened out. He could climb and not have to claw himself up, inch by inch.

Then he heard a roaring sound. “River?” he thought.

He stumbled down a slope, hitting some trees, and then saw lights ahead, a steady stream.

It dawned on him--a mountain pass highway was ahead!

Half frozen, delirious, Horace stumbled and crawled out of the snow and lay for a moment on recently plowed roadside. The traffic kept going by, semis and huge tractor-trailers streaming constantly in both directions, engines grinding on the slopes in low gear so keep up traction.

Moving down with them, Horace came to a truck stop. It was big, and he pushed in with a group of truckers, and fast-moving waitresses in buckskins and cowboy boots, and nobody stopped him. The diners were just as grubby, many of them, their hair sticking wild from their heads, bleary eyed, just as he knew he must have looked.

Even with his blanket, the diners had seen worse sights evidently as nobody looked at him twice or moved to shove him back outside.

He went into the men’s toilet, and sat in a stall to be by himself, warming up. Then he took toilet paper, wiping the melting snow from his hair.

Slowly, thawing out, he took off his boots, and dried out his boots by stuffing in toilet paper. He went and got paper towels too, and stuffed them into his coat and pants. That was better than feeling cold and wet.

Washing his face with hot water, combing his hair, he thought he would fit in, and maybe try to find something to eat.

The cafe was full, and he walked through, not trying to sit, and went back out. No money on him, he couldn’t afford to get the cops called. No, it was better to try to get a ride, or start walking again.

He started walking, and before he got ten feet a semi pulled over as Horace paused, waiting to see what the trucker wanted.

The driver called out. “Hey, Redskin! Saw you back at the Pussy 'N Boots. Ride along with me, and keep me awake so I won’t drive my rig into the ditch again. I’ll take care of your beer and crackers if you do that!”

“Sure,” said Horace, and he slung himself up into the cab of a Mayflower truck.

The interior was unbelievable. The warmth was wonderful, but the luxury, the plush everywhere, and the gleam of lights, the Country Western music from the sound system, the cold beer and crackers the trucker handed to him as the took off--Horace felt like he had stepped into another world, like a "homer," a homing pigeon on the wing that had lost all bearings on his home, as he had.

“I don’t know, just out walkin',” Horace said.

“Are you people crazy?” the trucker laughed. “Nobody WALKS in these mountains! We got a hundred miles of 9 to 14,000 elevation mountains, and there’s nothing between that first truckstop and Grand Junction--I mean, nuthin’, nuthin', and more nuthin'!”

Horace didn’t say anything, so the trucker shut up for a while, the music booming in their ears.

Horace finished his first beer, and the trucker, glancing over, handed him another from the refrigerator.

“Hey, wanna watch some boob tube?” the trucker offered. “Or, I got a good new video, a classic flick called TITANIC, you just gotta see. Lots of really big action stuff. The crunch with the berg. The ship’s belly tearing up. People running this way and that. Ship turning her big ass up in the water, then down she goes! Nice little love story too. After that I got--”

Horace, more interested in beer and crackers, didn’t seem to look excited, but the trucker slipped the disk in the VCR.

“Got a hundred or so flicks in my video library--you name it--the latest, I got ‘em. Maybe you like TERMINATOR II, or III, or IV--I don’t think V is out quite yet--or you like that old Star Wars crap--whatever, you can see it here! Oh, almost forgot X-Files. You name it, I got it!”

The screen in the dashboard glowed, and Horace’s attention was caught when he saw what Gabriel had chronicled, exactly, in every detail.

Yet it was not right. The iceberg. That wasn’t the killer. They had it all wrong. Horace lost interest, but the trucker watched it again, going through several boxes of different chips, medium to hot, a cheese-filled corn dog on a stick, and some cherry, lemon, vanilla, and chocolate pastries for dessert.

“Hey!” the trucker said. “Wanna ice cream bar? Got four kinds--French Vanilla, Strawberry, and this putrid Butterscotch I gotta get rid of since it drives me up the wall, the taste is so phony and won’t leave my mouth for hours.”

He reached into the refrigerator and got several, handing them to Horace. “Peel me a French, won’t ya? The first one.”

Horace peeled it, then handed it to the trucker, who downed it in a couple bites, then belched.

“Man!” the trucker laughed. “I can make good time, the road’s practically clear, and all the guys are back there eating at the cafe, and I have all we need here--so why stop and waste all that time? I just pick up somebody like you for company, and keep movin’. Now ain’t that kinda smart? Why waste all that time? I’d rather socialize back in Camden--you know, Jersey. I just gotta keep movin’ till I’ve dropped my load and picked up a return load. Then it’s movin’ again until I’ve made my next drop! Several times I do that, and usually I’m sitting at home while these other guys are half way through their routes. That’s their fault, they gotta socialize all across the country! Not me. If I gotta have some company, I pick up somebody like you--not too big, might make trouble, and not too stinky mean-looking. I had one guy who tried to hold me up--can you believe it? In my own truck? I got this rod here by my side, and I stuck it alongside his head real quick like. I learned that in Jersey growing up. My friends’ old men were Mafia, you see. I learned just enough from those friends, how to stay alive in this good ol’ USA.”

“Sioux Indian,” said Horace.

“Kinda figured it, but thought, hell, why not? I'm an equal opportunity redneck all-American trucker! I’ve picked up every race, color, and creed, why not a little Indian for a change? Forget old Custer, Chief Joseph, Wounded Knee, and all the rest! I personally got nuthin’, absolutely nuthin' against you Indians. I’m quarter Cherokee myself, my grandmother Whitebread down in Carolina or maybe Georgia, and she even wore her feather to church back in those days! But this one thing I can’t get over. They used to, those Mandan Indians over in Dakota country, used to hang themselves on meat hooks voluntarily in their secret ceremonies--now if that ain’t savage behavior, what is?”

When the trucker was through with Mandan meat hooks, Horace listened to how Indians had mismanaged the country, wasted its potential, before the whiteman came and developed it so that it was livable and productive, with roads and truck stops and all the rest.

The trucker laughed. “How did you Indians could stand it before we came and civilized it, I dunno! It musta been rough, having to go and kill your supper on the hoof every day! But, then, there was still a lot of buffalo and other game back then, wasn’t there?”

“I don’t know,” Horace said, after the trucker prodded him. “I just kill rabbits. There are still plenty of rabbits.”

That seemed to make the trucker think, for he fell silent. “He just kills rabbits, he says,” the trucker muttered. “What have these modern Indians come to? Bunny rabbit hunters! What kind of living can you get killing rabbits? You might as well be a pack of coyotes! Human beings can’t live on rabbits!”

The man’s voice wasn’t scornful, only amazed. He glanced over at Horace, who was finishing a third beer, and feeling the warmth coming back into his feet and hands. “You like that beer and crackers? A lot better than old stringy, jackrabbit, ain’t it? I bet! Hahahaha!”

Horace couldn’t be mad at a man like this. He was just much a good-hearted, old jackass, despite all the wrong and goofy things in his head.

Horace smiled. He nodded.

“Thought so!” the affable trucker laughed. “Here,” he said, passing another beer, “another for your health. That’s how I make it, myself. Good beer, no cigarettes to poison my lungs, some conversation now and then, plenty of snacks and flicks. It's life on the road. It could be worse.”

The trucker slipped in another flick.

By the time the night was over Horace was bursting with beer and crackers, ice cream and corn dogs--the dogs heated in the onboard microwave.

They stopped for the toilet at a rest stop, but didn’t waste anytime, and then resumed the trip through the Grand Tetons.

Late in the morning the worst was over, and the truck made really good progress on clean roads where thee was no snow. They stopped briefly to take off the chains.

Then the trucker really smoked the rubber on his tires as the road flattened out. They roared into the wide open desert. It was cold, high country, but open and free, and Horace, looking at it, felt better. He didn’t like the mountains. They smothered him, squeezed his spirit painfully. But out on the open ground he could breathe!

The trucker, too, seemed to relax. Driving was now a snap in comparison, and his cruise control cold take over. Leaning back with a beer, the trucker slipped video after video into his VCR. Horace, seeing the pornography, wasn’t taken by it, and looked out at the passing scenery. “Pretty hot and boring stuff, most of it,” the trucker commented, meaning his porn flicks. “But it reminds me of the old lady waiting for me. How about you? Got a nice little squaw waiting for you, little buddy, down in your tipi wherever it is you and your people live?”

Horace, shaking his head, looked out the window.

“Too bad!” the trucker observed. “It gives me something to work for, something to keep me going like this, knowing she’s back there in Jersey, waiting. You gotta get yourself a little woman like that. Gives you the compensation for livin’ this kind of life, and--”

The trucker paused, gave Horace the once over. “What are you, buddy? Still in your teens, ain’t ya? Boy, oh boy, I remember what it was like back then. The women we could get--whooie! But you gotta settle down sometime, you can’t keep partying like that. I had to find this job, and stick to it, or I’d have nuthin’, like some of my old buddies from Hilltop have nuthin’ because they were always chasing skirt and didn’t see someday they’d have to foot the bills. I wised up, and you see what I got workin’ for me--this baby is already half paid for, and ain’t two years old! I’ ll retire at forty five, fifty at the oldest, at the rate I’m investing. Maybe even move to Jamaica, enjoy the sun year round, like some guys who I know have made it in this racket.”

Miles down the road, the trucker came to a truck stop. Casino, strip joint, topless bar, gas, cafe, showers, giftshop, museum, nurse to give you shots for clap--it had everything, and signs announced its services for miles, telling travelers how close they were getting with each passing mile.

The trucker called over to Horace, whose head was nodding on his chest. “Hey! Wake up! Grand Junction comin’ up, Tonto! Wanna shower and shave? Wouldn’t hurt you, I reckon. Well, I’m goin’ in and blow out my pipes a bit. But if you stand on the road out of town and I see ya, I’ll pick ya up. You been pretty good company so far. You don’t talk too much and interrupt me, and don’t cause any trouble, like complaining about what’s on the menu or drinking yourself stupid, and throwin’ up in my cab like some of these bastards I drag off the side of the road!”

Walking through the big lot, Horace’s feet led him through the maze and he found the road, and then the highway. But on the exit, he stopped, remembering the man’s words. But something stirred in his heart. It was Gabriel, telling him something back in the Twins.

“No,” he thought. “I don’t see why I should care about these Wasichu. They come here, take our country, change everything, stomp us down to the bottom, and--” Though he saw the Mayflower slowly coming his way, he turned and walked away from the road, heading across country. In the distance, the Mayflower slowed down, honking, and then drove on. His lungs filled with fresh air, wind on his face, light on his whole body, he felt free, and he didn’t want to lose what he now had. He knew he had the best of everything, the Wasichu was mistaken. That truck was his trap, a coffin he carried with him. He’d never know a single moment of free wind, free sky, free rain, free sunshine, free anything--as long as he drove his Mayflower! “Those people are ignorant since birth, they just don’t know anything,” Horace thought, thinking more kindly now that he had some distance between. But who could tell them? They wouldn’t know what they were being told. It would make no sense to them. They thought they had everything they could want. They weren’t asking anything, just telling and telling.

He walked on, and after several miles he came to more carvings. The lands that fed into the Colorado were rich in carvings, he discovered. It made his journey so rich to find them, and then see what they said to him.

But ranchers or even tourists, in places, had found them too. They had left their initials, drawing modern things that looked crude beside the Paiute carvings--plain stupid things like “Only Good Indian is a Dead Indian,” next to “Yeah! Shoot the Redskins Twice, Once in Head, twice in the B.I.A!” Or warnings such as “Private Property, Keep Out!” and “Trespassers and Oddaboners Shot, Skinned, and No Questions Asked.” These things made Horace sad again. The whole land was tainted, spoiled, he felt, whenever the found the carvings defaced or scribbled over.

How beautifully the Paiute brothers and sisters had carved relatives-like! How beautiful were their stories!

Horace kept finding more carvings as he continued. He slept, walked on, and found himself in a river gorge. Gold and red cliffs, caverns, bridges of stone, caves and caverns, the land was full of wonders, and between it ran a great river.

With no Wasichu distractions or disruptions of the landscape, though now and then a jet left a contrail in the sky, he could feel like his forefathers felt before the Wasichu’s coming. It was wonderful. He felt a century or more of defeat, humiliation, and reproach fall of his shoulders and head. Tearing off his Wasichu clothes, he dove into the water of an eddying pool by the bank, and gasping rose out feeling the Wasichu curse had been completely washed off.

Crying out his Lakota prayer of thanksgiving, he stretched his arms, wheeled about on a big, hot stone, so that the four corners of the world could hear his forefather’s words.

Then he stretched out on the stone, feeling its selfhood and warmth and joy pour into his wet, shaking body from head to toe.

When he sat up to comb his hair with his fingers, he looked at the discarded clothes. Except for the blanket, he despised what his people had chosen to wear.

On impulse, he grabbed them and tossed them into the river. The current quickly swept them away downriver. Now he could wear his own skin the Creator had given him. He wasn’t naked!

Now he was really free! No Wasichu was free as he was free, he knew.

so then he had to use the roads in places, which he hated. They had destroyed the river with the dams, but in other places they still let it flow free, and there he found ways to climb down to it, so he could follow it on foot.

The walls spoke back to him when he spoke to them.

“Why should I warn them?” he shouted. And the words repeated, over and over, fading gradually, with no answer coming back to bring the pipe to his heart. “Gabriel--Ga-bri-el!” he called, and the same thing happened, only he knew what Gabriel would say, and had said. “No, I will forget what you taught me!” he continued. The words came back, haunting him this time. His feet began to itch and shift back and forth, and he went on.

“Nobody goes here alone like you!” one insisted, ignoring the fact Horace was buck naked. His eyes glued to Horace’s chin, he asked Horace his business in the gorge.

“I’m looking around at my country,” Horace said. What else could he say?

“You’re pretty brave to do that! Even living off the land? Wearing no--Wow. I’ve always thought I’d try that someday, but joining a nudist colony isn't--”

Horace said nothing, and finished his soya-tofu-sesame seed pancakes with Save the Amazon rain forest fruit topping, and rice-based pop substitute with herbal Root Beer flavor.

“Thank you,” he said and then left them staring at his bare behind.

Horace, however, used to his nakedness by now, hardly cared what they thought. Even the truck driver’s company wasn’t this bad. His spirit nearly sucked or crushed out of him, reduced to a little Indian, and a silly, naked one at that, he felt like choking, for some reason. These people--so casual and friendly, but dressed in tee shirts and comfortable sweats with messages about the environment and the whales and other things he could see, at a glance, costing no doubt thousands of dollars. Cameras, camcorders, the ziplock carrying bags for everything including their waste--it made him sick somehow. The hair styles, the designer ecology jewelry and sun-powered Seiko watches, the color-coordinated clothes and gear--they were just the Wasichu in the Twins. Even looked the same, not really any different than they looked in downtown Minneapolis or at the Supermall in Bloomington. Yet, everything they had said, not so much wealth and luxury, but what money had bought them--invincible power. They had the power over the earth, and the rest was a masquerade for manipulating, grasping, using all the powerless.

Brother eagle, Brother hawk, long-tailed brothers, a funny, long-necked Roadrunner that came for any scraps he threw it, deer, lizards, burros, prong-horns, even a furry, fearless cricket he could take on his finger.

In their company he was far from being alone. Whenever he stepped out of that company in his thoughts, he felt instantly alone, cast into whirling, broken-edged darkness where nothing had its place or could keep it.

How surprised he was to find a mustang band had somehow made its way down to the river. A pinto mare, pony-sized, lingered after the others had finished drinking and scrambled back up the slopes beyond his reach. He was careful not to alarm it as he approached in a way he had learned with wild things.

When he was close enough he leaped. For a few moments he was given the ride of his life, before the wild spirit slipped from beneath him and vanished among the rocks above him.

Besides repeating his own words, the canyon was speaking many things to his spirit, that no place had ever spoken. He wasn’t sure he was hearing everything, but he was trying to hear more and more. The water, the rocks, the waterfalls, the pools, the lizards and snakes, the birds and trees--they all said wise things to him.

He was still thinking, too, “Gabriel is wrong. He crusaded. His problem was he wanted to save the world, all the Wasichu and all us too. Nobody can do that. They won’t listen, leastwise to us ‘little Indians’.”

This thought dogged him, and he couldn’t rest as long as it was with him, though it should have settled the war in his heart.

Horace groaned. How was he going to get round this? He needed clothes to elude detection and the cops stopping him.

“Maybe,” he thought, “I can wrap my blanket round me and get through?”

It took some preparation, getting up resolve, and then he decided to push forward, right through it.

After being out of this world for so long, it was like he was some coyote brother creeping through downtown NYC, hoping to be unobserved, as he slipped through the first of the motorhomes emblazoned with “Wilderness!” and “Apache Country” and ““Commanche Dreams,” even “Dream-Catcher.”

His nostrils used to the free, scentless air, he noticed at once how bad everything stank about the Wasichu--the stink of stolen, corrupted power. Groups of youth, holding girlfriends by the hip or even the breast, a corn dog in the other hand or a pop can--they smelled real bad downwind. It wasn’t sex or any other thing--they were, his eyes could see, all playing power games with each other, using and grasping and then discarding the powerless.

As he moved through all the motorhomes, parked ATMs, BMWs and stretch limos, barbecues and portable gift shops selling Indian souvenirs and crystals and dried desert flower arrangements and all the rest, the odors almost made him double over. It wasn’t gas or exhaust fumes, bad as they were. It was something else--the fatty, rancid, sour smell of power that came out of the Wasichu’s very pores! It put clouds of invisible grease in the air, and he was walking into one cloud after another.

People glanced at him, of course, and security guards for the camp gave him a second look, but he wasn’t any different looking than many who wore long hair, stripped to the waist, and wore ragged-ended, cut-off jeans and bare feet. What was a blanket when everyone dressed as he pleased nowadays? Besides, the eagle emblems made him extremely fashionable, on the cutting edge amidst luxury motorhomes all claiming to be one kind of Indian or another.

Horace, feeling the eyes, nevertheless, kept moving to the perimeters of the motorhome-boat city.

When he was finally clear he blew the air out of his lungs, and took gasping breaths of clean air.

Walking fast, he was passed by huge motorhomes the size of Greyhound buses, going in and out of the camp, not to mention Harley-Davidsons with someone a sidecar or a trailer behind.

Horace, having never been in these resorts, could not believe what he saw--the fabulous display of wealth, as if money was so many leaves on the tree to be picked and scattered to the wind!

His blanket-motorhome still around his body, he continued walking down the highway, which was covered with rabbit carcasses all smashed flat, and intending to climb off and around the camp as soon as he could find a good spot.

A black, gold-dusted bike roared up alongside him, nearing throwing him into the ditch.

Motorhomes and limos were rushing by Horace couldn’t hear the shouted words from the guy with the sunglasses, but he was pointing to the empty seat behind him.

At first Horace hesitated, but the guy wouldn’t give up! So to get rid of the guy, Horace flashed his backside, and the biker said, “Hey!--cool!--got nerve too!” though Horace couldn’t hear. The biker looked up and down the road, saw the attention they were attracting, seemed to change her mind after another glance at him, then dug out a pair of jeans from her pack and threw to him.

Horace, with utterly no control over it, held on for his life, and the bike hit another invisible barrier in changing gears, and again they flew forward seemingly at supersonic speed. Since they were only blurs ahead in the heat hazing the road, impacts with rabbits were unavoidable, and felt like they were hitting moth after moth. Splat! Splat! A pause.

Then splat! splat! splat! Sometimes a rabbit, or part of it, was kicked up by the wheels and went rocketing up into the air behind them. Once Horace felt something and looked down, and two legs had caught on his leg, held by the pelvis bone between, and were kicking away as if all the rest of the rabbit were still there.

He hated the biker then, but he couldn’t stop the bike. He had to wait. His eyes blurred, Horace could only look sideways and backwards, and saw the distant mountains and flats do strange things. They were either rapidly galloping away or galloping toward him, and he seemed to be, with the biker, the center of the Universe, not attached to anything but the rocket beneath them.

Horace was shocked beyond words when the biker, in the midst of this, handed him a cold beer.

How could he hold on to his seat and beer too?

But he took it and immediately lost it. No matter. The rocket bike continued on.

After a while Horace sensed a shift, even though he didn’t hear or feel anything different.

Then suddenly, the Wasichu world rushed back on him--sound, smell of power, confusion--it was a truckstop. Signs blinking everywhere, vehicles all over the place, noise blasting from all directions.

The biker hopped down, pulled off her helmet, and Horace stared goggle-eyed!

The cafe boomed inside with clashing sounds and jukeboxes and slots, air half-grease and half-smoke almost blinded Horace--but he followed the biker and they sat at a booth.

Horace didn’t say a thing. He didn’t need to. She ordered breakfast, though it was evening, and soon he was making his mark on a pile of pancakes and eggs and bacon.

All he time he ate she was saying things he didn’t understand, and couldn’t hear in the clatter and confusion of the cafe, and she didn’t seem to mind that he didn’t talk back. In fact, she seemed to like him the more for his silence.

A strange thing though--on the way out after she paid up for them, she pulled him over to a photo booth. Since he had no shirt and she pulled her tee shirt off him, it looked like he hadn’t anything on in the photos. She looked at them, hooted like a cowboy, gave him one and kept the rest, which she stuffed in her jacket.

Outside, she thumbed toward her vacant seat, and he got on again, letting the tee shirt and photo drop behind as off they went!

The second trip on the rocket landed them in Vegas just as the lights were really turning bright.

She ran up a casino-hotel driveway between palms and sphinxes and parked under the lights proclaiming the name of this latest addition to Vegas's skyline.

“He’s showed me quite a bit more of his resume on the road, of course, but that was in a respectable truckstop, you understand!” she laughed.

The other “galley slaves” looked at him, with respect. White and sometimes black girls with hair shaved close like boys, earrings in their noses, and tattoos on their arms, and blacks and Chicanos who always were glancing at the girls and making remarks only they could hear and patting their bottoms whenever they passed by.

The girls were by far more aggressive, toward each other and to men alike, and were bad mouthing the management that was underpaying them. Since he looked Indian, they figured he had a knife or stiletto somewhere and could sneak up on them like Indians do, so they didn’t mess with him.

But one young Chinese guy serving as busboy came close to him, smiled, and introduced himself as a friend, and offered him some cocaine or anything else he wanted after hours, and Horace looked at him, and the fellow found something else to do. There was little to doing the job--running a dishwasher hour after hour, stacking the clean in the trays, which someone else took out to the food preparation areas.

The two-thousand room hotel was sixty stories above the casinos on the first two floors which, along with entertainment shows, bars, cafeteria-restaurants, discos, boutiques, “love-in Jacuzzis,” ran day and night. The pace in the kitchens was hard and furious. He had kept up, but he was worn out. No one had come to tell him about breaks, and when the others left periodically he kept working and no one said anything.

He drank from a fountain, forgetting where he was, just like dog, then washed his face as two pencil-thin look-alikes, one with a walker, paused to stare at him and shake twin blue haired heads. Hardly able to keep his eyes open, not caring to go out into the heat and be busted by a hostile cop or security guard, Horace found places where he slept, disturbed only when workers came to get a mop or broom, and then he moved on to another spot.

Sometimes it was a quiet alcove with big potted ferns to him as he stretched out on a sofa with nobody coming near it for over an hour. He had brought his eagle blanket in, fortunately, and now it kept him warm against the frigid air-conditioning.

The alcove stayed his until the morning, and then vacuuming people came by, and he had to move. He went outside, then realized that his uniform was spotted, and security people wouldn’t let him stand outside, so he had to go back in, or leave the grounds entirely.

He took a quick glance down the avenue, seeing huge casinos and signs, but nothing like Minneapolis. Where was he to find a place that sold ordinary clothes? He didn’t have money anyway.

He walked back through the pyramid, pausing outside several boutiques selling most Frederick’s of Hollywood lingerie and accessories. Camel-necked mannequins with enormous wraparound sunshades and breasts covered with sequined bras and bottoms sporting black and gold-striped panties--nothing for men, though he saw some men in casual Audubon hiking shorts and sandals carrying women’s handbags with straps over their shoulders, going in.

The prices--all in the hundreds or thousands, but mostly in the thousands. Even the prices stank of power--the smell poured out of the high-priced items, right through the thick glass windows.

He gave up and went to find another hiding place, for the casino was strictly off-limits to service personnel--he could see that at a glance by the way security guards eyed him the moment he put his head into the area through a doorway.

Security was thick, and he didn’t know, he thought it was that way all the time. But someone had run through the day before shooting customers and guards, and the casino had every uniform available on someone, and carrying a gun if they were licensed or even if they weren’t licensed.

At two o’clock he escaped back into the kitchens and was given a meal on his break after he had worked a couple hours. The food was excellent--the same quality in everything. Marty saw to it personally, always checking dishes that went out, whether to customers or his own people.

The second week came, and Marty took his pay, went to the slots and lost every dime. Now he had B.I.A. coming him, if he took the time to apply at most any government office in town, but he didn’t give it a second thought and his itching feet soon took him out to the road where he had come in.

He never did learn the biker’s name. She had her friends to look up in Vegas, and to her he was just another roadside John, as Marty had explained.

Here too he could always find a place to sleep for nothing, and he had his blanket along, and that was enough for him. Cleaning up in restrooms that were equipped with showers, now was replaced with swims in the river and drying out on the rocks.

Fortunately, he had his fishing rod! It had been hard taking it along different places at Vegas, but the town had seen stranger things, and nobody stole it when he had to leave it parked someplace in a planterbox or a closet--whatever was at hand.

Now it was his bread and butter as he went to work on the river’s pantry.

He had matches, too, in a zip-lock bag. Matches were one thing for which he could thank the Wasichu--they made his fires so much easier. With a fire to warm the night and fry his fish, to make the night beautiful too, he didn’t need much else.

But the silence, the stars, the beauty--he couldn’t fill everything inside himself with them. The questions came back with double strength. Vegas had pushed them down out of sight and hearing, but now there was nothing between.

He found himself stopping on his walks to shout at the canyon walls again, and they talked back to him his anger, loneliness, and grief.

Would he ever get free of his traveling companions? He wanted only to be alone, but they would not let him go.

By the carvings he came to he came to see he was in Hopi and also Ananazi country. He also crossed a bit of Navaho land. Whatever tribe, the carvings said, “Take joy, brother! See the game here! See the corn we raise! We offer it back to the earth who gave it, with dancing steps, and we, the hunters of the deer and the growers of the corn maidens, we carve these letters to you, so that you can rejoice with us in these good gifts!”

Horace did take joy in the river’s good gifts. The river sustained him, feeding and washing him and protecting him with its high walls. He was bathed in its goodness day after day.

He was startled when one day the words formed in his mind:

He started to walk, then was stopped when the words started again.

That was what Gabriel had become! That was what Gabriel had tried to get him to do--and failed. That tear Gabriel had shed? His mother had taken it, because it was everything Gabriel had dreamed, and nobody would take it from him to give to the Wasichu, so she had to take it and bury it with him. Or maybe she didn’t bury it with him? He didn’t know.

Just now he felt he should feel in his blanket, and he no more than touched it when the vial rolled out.

Horace, shaking his head, backed away. Then he went forward, touched it gently, then grabbed it. He pulled his arm back, intending to fling it as far as he could.

Something seemed to hold his arm back, and he could not throw. Wrestling with the unseen force, Horace tried to throw the vial into the river, but it was impossible.

Gasping, Horace relented, and his arm was released. Standing, still holding the vial, Horace thought fast.

He wanted no part of helping the Wasichu, the enemy who had come and destroyed the Lakota, Nekota, and Dakota. Yes, he had lived among them, but hated every minute of it. For Gabriel’s sake he had endured it, but now there was nothing to hold him. Forgetting about throwing Gabriel’s tears away, he decided to put to keep the vial. Maybe then, he thought, he wouldn’t be disturbed by whatever brother spirit was bothering him.

Time passed as he walked--the vial inside his rolled up blanket--and he wasn’t disturbed again, and he soon forgot what the words had told him too. He thought the matter was over.

Then the words broke into his world, once again so unexpectedly he had no time to think of a way to shut them out.

Immediately, pictures filled his mind. The Mayflower trucker, the biker-lady, Marty, the rafting parties. All Wasichu, of course.

Horace, gritting his teeth, took off, climbing rocks, and trying to put some distance between him and what he had been told.

Coming to a side canyon, he ran up it, and then entered a cavern, which led far back from the light. Horace didn’t care. He just didn’t want to hear any more words like he had just heard.

He heard something else, however. A roar, from something tumbling toward him. Then it dawned on him as he heard water, a river of it. A flash flood!

He spun on his heels in the sand and dashed away, but the waters that filled the cavern to the ceiling twenty feet overhead were much, much faster.

Suddenly picked up and engulfed, Horace was spun around, thrown forward, and the waters rushed onward, finding the entrance, where they shot out with a blast that carried him hundreds of feet with millions of gallons sounding like dozens of freight trains all in the same tunnel. Blasting its way, the river excavated its own hole further down the slope to the river, and down the flood went, still carrying Horace like a tiny flower seed within its surge!

A short time later the water boiled and spouted up across the river, and Horace shot out, half-dead.

Then he collapsed. When he had the strength, he staggered to his feet, retching out what he had swallowed.

He lay there time out of mind. But the night was coming on, and wind was cold at night. With no blanket, he had to find shelter. He moved upwards toward the cliffs. Instinctively, he thought there had to be shelter among the rocks, and there was--caves, honeycombing the entire area as far as he could see.

Not overly particular in his condition, Horace took one he could climb to without too much difficulty, hoping it was high enough so he wouldn’t attract any bear, panther, or wolves in the area, since he had no matches for a fire.

Strangely, he recalled the vial just then. He had lost it! Feeling now a loss he could not explain, he went back down to the shore. With so big a space to look, it was impossible, of course, to find so small a thing. Yet his footsteps took him exactly to where it was lying on the sand, and there was just enough light to see it.

Snatching it, he hurried back to the cliffs and the chosen cave. Moving in to it, he no sooner went a few feet then he nudged something that wasn’t rock. Feeling with his fingers, he found a very large, canoe-shaped basket, large, without a lid. Alongside where others too, all varying sizes, and all lidded. Whether old or not, he could not tell, and though snakes and scorpions might be filling them, he was too tired to care, and he climbed into it.

His arms around himself, he dreamed as soon as his eyes closed.

Words came to him from the basket canoe's makers. “Catch the dreams, they are evil, and they will be changed to good. You are the dream-catcher, and the Great Weaver will guide you!”

“No,” Horace murmured, but the dreams came anyway--dreams his cousin had already mentioned to him in a distant city--only these dreams came clothed in the thoughts and words the Lakota used, with very few Wasichu words, except where the Lakota had words to describe Wasichu inventions.

He saw the Messiah-Brave, only Son of the Great Father Spirit, leaving the Great Council Fire to live and fight for his Father on Earth, stripped of all his skin and scalp, leaving them shining in his Father’s sky-lodge, and how like a star his skin and scalp went seeking for him on Earth.

But the stone rolled back, and two braves shining with such brightness that the guards fled, took their places. The Son stepped out, then walked away. Later, a woman, then two, came creeping toward the cave, and they saw the Son, and he spoke to them, and they ran off.

One of the two men who had taken the Son down from the power tree saw the Son alive, brought forth from death, and he got on a ship and took this news to a far country of many islands, where he told the people everything the Son had done for them. When this man was old, he blessed the land and the people, and the blessing remained to guard them against their coming foes.

Horace saw many other strange things.

A man sat in a big chair and it flew off toward the moon. Then a boy, living very well in a good family and in a nice tipi, was seized by rough men on a raid from a ship, dragged on board, and taken to an island glowing with lush grass like a green stone, where he was put to work naked and herding sheep in the rain and cold. When the boy prayed many prayers, he was told in his sleep to go to the coast, and a ship was waiting to take him to his lost home. This the boy did. He fled his slave-keeper, and found the ship, and was taken across a water to a strange country, where he and the men wandered looking for food.

The brave prayed, and a herd of pigs came running, and soon they had more than enough to keep them from starving. Then, with no cities left unburned by the enemy in that country, with no one to buy their greyhounds, the men went back to their ship, and the brave sailed with them to his own country, where he returned home.

Then in a dream a man from the country that had enslaved him cried and pleaded with him to return, to bring the people there light and deliverance from darkness.

Waking, the brave remembered the dream, and he obeyed, returning to the people who had enslaved him, and they heard his words and were changed, and the brave built many churches throughout the land, wherever he stopped and preached and baptized the people, just as the Black Robes had done to many of the Lakota.

Someone, afraid of the writings, tried to burn them, but they would not burn. Afterwards, the writings were taken away when tribes came to burn the stone tipis of the Black-Robes, and on board a ship they round the whole country to the south until they came to rest in a warm land, with Black-Robes to care for them for centuries to come.

This chieftain’s name was Alfred, and he found sanctuary on an island in the swamp, and it was easily defended, so he was safe and could rest before going out to battle his enemies again. The island was fertile, and large enough for some farmers to live, and the chieftain was fed by an old woman in her house where he was staying.

She asked him why he was fleeing the wild tribes of the North, and didn’t go out to defeat them. The chieftain answered, “They are many, and we are few! They have boats, and can always bring in more warriors, and--” But the old woman, who fed him his dinner, wouldn’t listen to excuses and pressed him. “You can’t save your people sitting here, talking to an old woman! You must think of something, some way to get the best of them.”

Unable to argue with that, the chieftain swallowed his pride at her rebuke, and he thought long and hard as he ate the simple but good wheat porridge she cooked for him. “ Why must I wait for them to come into the country?” he thought after a time.

“Why give them time to assemble and increase their strength into armies, so that I am hard-pressed to find enough fighting men to meet them in battle” The idea had come to the chieftain’s brow, how he did not know, but it struck him like thunder.

Yes! He would go forth from Athelney, the island in the swamp, and cut off the invaders at the seacoasts, while they were landing and were most vulnerable. Or he and his men would lie in wait for their long canoes to come up the narrow creeks and little streams.

Then they would sent arrows out from cover of the thick bushes and trees, killing them all! That was the way to fight them and throw them back!

Not by pitched battles, which they could win with superior numbers, but by stealth and cunning and patience, working the land against the invader, and using the land itself to beat them!

Doing this, the chieftain of the Angles and Saxons pushed the invaders back, and made them smoke the peace pipe and sign a treaty that held them to a certain territory.

This saved the country that was “Angle-Land,” later called “England.” This same great chieftain, when he was old, dreamed. He saw his beloved country added to another and another until a chieftain ruled the whole world from Londinium, his capital. He saw the terrible overthrow of this chieftain, and other things too which made him weep on his deathbed.

Fleeing from England, wanting freedom, they invaded the Turtle, thinking it was free to take. Settling on vacant land on the coast, where a tribe had died from a Wasichu disease off the passing ships, the Wasichu settlers built their lodges and went looking for gold, and nearly all starved to death the first winter, or got sick and died.

But tribes came and showed them how to grow the Three Sisters, and after that the Wasichu lived and ate well and increased in numbers so much they devoured the whole country and forced the tribes out.

This brave was the same man who helped to write the Wasichu’s Great Covenant of the Council Fire by which they governed all their council fires in the generations to come.

Then another of the Wasichu’s fathers rode forth with other braves to fight the French and Iroquois, and they fought poorly, so that the Iroquois could shoot them down without aiming, since the men stood up and dared anyone to shoot them, or at least that is how it looked. The French and the Iroquois shot hundreds, and especially wanted to kill all the chieftains, but one they could not kill.

Bullets puffed in his clothing, but he did not fall from his horse. His horse was shot from under him, he got on another, and still the bullets would not kill him.

Finally, the battle was over, and the one they could not kill, though they could pierce his buckskins with many bullets, rode off. This man was another who wrote the Wasichu’s Great Covenant.

The war over, the Wasichu flooded west into the lands of the Lakota, Nekota, and Dakota. They all fought the Wasichu, but when the Wasichu killed the buffalo, the people starved, and they had to stop fighting.

Put on the Rosebud, Pine Ridge, Brule, and other places the Wasichu chose for them, the people gave up their spirit. The Sacred Hoop was broken.

The Black Robes, too, were some who did good to the people, giving them the Book of the Messiah, and showing them ways to learn and build and live on the empty plains, not that their mainstay, the buffalo, were gone.

Yet the times continued very hard.

They had known plenty while the buffalo ranged the whole country down the back of the Turtle, so numerous they could not be counted, while overhead the multitudes of delicious pigeons flew back and forth. Fish and pools and lakes were choked with good fish, and the rivers--but the Lakota knew few rivers in their grassy and sparse-wooded lands.

Two chieftains fought each other with their warriors, and many died, and then one, who hated the rival who sold land to the Wasichu, retreated into a high, lake country.

There he lived many years with his remaining people, and finally Te Hapuku--his name--was old and dying in his pa. Surprising the people, a Wasichu chieftain came, bringing along the hated rival, Karaitiana.

Horace, in this sleep, expected to see the dying old man curse his enemy, and then die on his bed. But no! The two men wept at the sight of each other, and embraced!

The Wasichu, who had brought the two chieftains together in reconciliation, he was shown great honor by the people now, for word of this great deed of his spread quickly through all the chieftain’s encampment beside the lake of Te Aute. They showed him the power carvings of the chieftain’s pa, which told of many events in the future, things held secret for ages were made known to him.

Horace saw a man who dug in the ground with many others with shovels and picks, then loaded small travois, which were pushed out on tracks to another place where the coat was dumped, then hauled to the surface, where it was loaded again into iron horses. This man left the work and went down to live by the sea, and he sat there and prayed, and a tipi rose over his head to shelter him from the rain and cold, and others who prayed joined him.

Horace next saw a Great Canoe called “TITANIC,” with thousands of powerful Wasichu aboard, as well as many who were not wealthy and powerful. On its first voyage, it was sailing the Western Water in the north toward the Turtle when it was struck and sank to the bottom of the sea. Yet before this happened a Wasichu woman prayed and sat up while others slept, for she knew that the Great Canoe would sink. On the Great Canoe a little girl dreamed and saw the sinking, but no one would believe her.

Sometimes he quieted, when the messages sank in, but mostly he fought what he did not want to see. It was not pleasant to see the sinking of the Great Canoe, however much he hated the Wasichu and wanted them all drowned because of what they had done to his people.

Yet, beside all they had done, he was forced to weigh the lives and exploits of many that were good, and the lesson of whole series began to make a mark.

“No!” Horace protested. He wanted to stop the dreaming, but it seemed he was stuck once his heat touched the Great Weavers’ basket, the one that held their seed-corn. As much as he resisted, it was like trying to stop the flash flood that had carried him from one side of the river to the other!

Once caught in the flow, he was going to be taken, whether he kicked and screamed or went quietly, all the way. There was no turning back!

Next a singer from the same island where the young slave had been taken by force from his home to by raiders to herd sheep as a slave, this sage and singer went to look for old calfskin books he knew existed, and found them in the southern land where the Black-Robes set up their first tipis. The calfskins, which were written by the Black-Robe of Wearmouth-Jarrow, warned of the soon coming Second Great War, a war which would usher in a new world and a False Messiah.

To help stop the armies of the “Fuehrer,” the first and second horses, the Lakota and the Wasichu who were joined in prayer-battle, prayed with their helpers and major victories were won for the countries that stood against the Fuehrer, Herr Schickelgruber, who ruled over the nation of the Germans, and then over many conquered countries and peoples, killing whoever he pleased, particularly the Jews whom he hated most.

One warrior’s wings were shot off, and yet his eagle continued to fly, and he was taken to the coast where he saw a strange thing happening.

Shickelgruber had sent an army in the air, and also an army on the water. But the channel was frozen, and so it was an easy thing to send his warriors across now, and they came pouring toward the English coast by the thousands. Yet a woman, living where they would first appear, was praying that day, and caring for her sick mother. She prayed and then, her thoughts turning to Joseph, said an old prayer that came to mind.

Joseph of Arimathea, who had come to Britain as an apostle, telling the good news of Jesus’ resurrection to the Britons, and founded a church at Glastonbury, this Joseph’s blessing was the prayer she prayed, though she could not have remembered it, it not having been written down. The moment it passed her lips, something happened at Chesil Banks, for this was Abbotsbury, where she lived, an old, stone village next to a miles-long dune of gravel called Chesil Banks, which was formed by the most powerful, scouring tides on Earth.

What occurred caught the advancing columns of Shickelgruber’s Nazi hordes by surprise. The ice gave way just before the Banks, and the forward units plunged in, and since mist poured out and covered the area, the army kept rushing forward until the entire force called Operation Sea Lion was drowned! The ferocious tides beneath the ice spared no one, and the men in the water could not climb to safety, for all was ice around them.

England was saved!

The blessing had been activated at the precise moment when it would prove most effective, and at the precise point where the tides, ice, and mist could fight more fiercely than anything that a hard-pressed England could muster.

Over on the continent that Schickelgruber ruled, however, the Jews were being exterminated. Ilse was a Dutch Jew, and she was put on an iron horse, in one of the wooden wagons, and sent to her death in the gas ovens Shickelgruber had ordered set up on the Polish plains.

Millions of her people were thus put to death, but not before they were starved, beaten, raped, and worked until they dropped.

This young Jewess, though blind, was shown a miracle.

Her rag doll, lost in childhood, was suddenly given back into her hands, and she was asked if she would go on a mission--there in a gas chamber, at the moment of death!--to help win reconciliation and peace for humanity.

Three chieftains, and the Red Star, which had sent the Great Canoe to the bottom of the sea, now directed the chieftains, and afterwards, when their words were going out to the waiting world, the star followed one of the three-- the Wasichu who came from the Turtle and Bear.

This Council started the War of Ice, a war that divided the world into two camps, and two council fires, and the two camps were filled with warriors dressed and ready to make war at a moment’s notice. It was a terrible time of constant threats and great fear, and wars were fought, one side gaining advantage, and then the other side would fight and gain some advantage, and this went on for many years until both sides had spent much wealth on their weapons, to the point where they could each have killed everyone on Earth several times.

One old man had been a farmer, who had lived in a sod house the first Wasichu first dug for shelter on the plains of the Lakota, Nekota, and Dakota.

His heart was struck by the Red Star too, and though once a good man he had been changed, and to heal him the healing took a certain medicine that was most costly and hard to obtain. In fact, the medicine was the loss of his most valued possessions--his own son, and his beloved son-in-law, who was like a second son to him.

Another Wasichu, whose heart was corrupted by the Red Star just as badly, betrayed the son-in-law and the son of the farmer, and they died because of it. Their sudden deaths broke the heart of the old farmer, but the medicine changed him, and his bitterness was cast out.

The son-in-law’s father, too, was given a new heart through the loss of his son. So much good came from what seemed evil at the time.

How this happened, and why the old men did not turn more bitter, is a mystery except that the Great Weaver was active in all the weaving.

It was deserted, however, and he froze to death, but his precious calfskin painting were preserved by his putting them in a refrigerator.

These calfskins would then form a letter to be sent to a certain tribe lost among the stars.

Now the Great Weaver People began speaking again to him. “You will find your dreams upon the Earth after you catch and give back what you catch to your enemies.”

Horace didn’t like the sound of this wisdom now any more than he first liked it. He began to fret and resist.

“Your people’s Hoop is broken,” the Weavers reminded him. “Listen to us! We restored ours in a way you must restore yours, if you choose rightly. If you wish to gain yourself, lose yourself for others. Beat their drums, dance their dances, sing their songs, dream their dreams! You have been shown many things already. Have you forgotten them already? The one who destroyed the dreams of others, so that his alone might live, where is he? Has he not, with all his dreams, perished from the Earth?”

Horace grew quiet. He knew the Weavers referred to the one called Schickelgruber.

Horace’s heart surged at this point, and it felt like it would burst. It was Gabriel, not just the Weavers of the Dream Baskets amongst which he slept, that was speaking to him! He knew it! Gabriel his brother! And this was the Secret they were trying to give to him--if he wanted it, that is.

“Weep with their tears, laugh with their laughter, suffer with their pains--” the Weavers continued.

While they spoke Horace saw the Great Canoe setting forth into the Western Water, thousands aboard cheering and waving to other thousands gathered on the shore to see them off.

The contents dropped on Horace’s face and eyes, anointing him, and he awakened.