Before the Lakota recorders, Jason the captain of the Argo, who led the Argonauts' expedition to regain the Golden Fleece, foresaw this apparition heading for Earth:

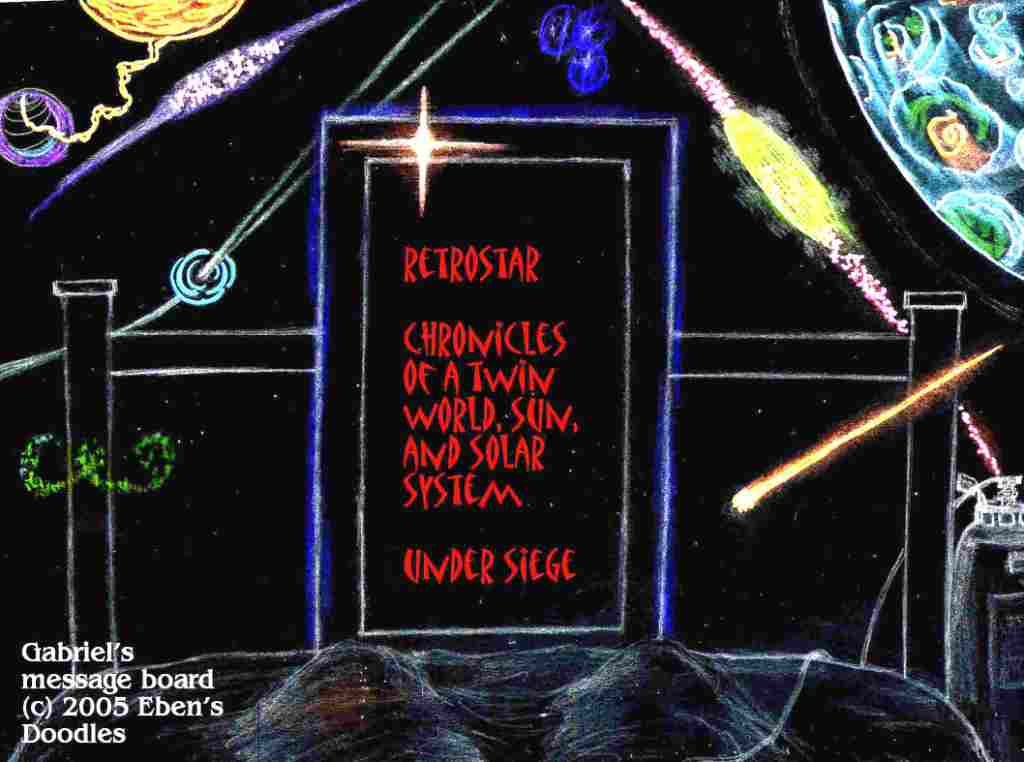

R E T R O S T A R

D I R E C T O R Y

A N D

L I N K I N G

P A G E

RETROSTAR, OR, THE CIRCULAR WEB:

Chronicles of a Twin Earth, Sun, and Solar System Under Siege

Dedicated to Gabriel Tall Chief who first blew the horn and to M.G.Y. (Marty Gantry Yeager aboard RMS TITANIC) who couldn't hear it...

WELCOME TO THE TWIN EARTH(S)!

THE TEN STONES OF FIRE--Ezekiel 28: 13-14:

"Thou has been in Eden the garden of God; every precious stone was thy covering, the Sardius, Topaz, and the Diamond, the Beryl, the Onyx, and the Jasper, the Sapphire, the Emerald, and the Carbuncle, and Gold...thou art the anointed cherub that covereth; and I have set thee so: thou wast on the holy mountain of God; thou has walked up and down in the midst of the stones of fire. Note: Each fiery stone of heaven is corrupted by the fallen cherub, Lucifer, the "Light-Bringer" who was Keeper of the Stones, and it acquires a different character and a guiding deadly creature of evil genius hidden within it.

WELCOME TO VOLUME I, FATAL CONVERGENCE! This is the point of entry for the First Alien Entity!

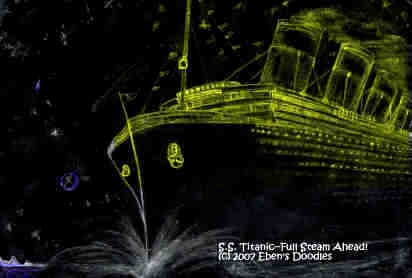

The great, state of the art, "unsinkable" Ship of the World has set sail on its maiden voyage with its cargo of fools, both fabulously rich and contemptibly poor, educated and uneducated, moral and immoral, beautiful and ugly, tall and short, nice tempered and ill-tempered, with nice teeth or with bad teeth, brown eyes and blue, or black and hazel--a complete human spectrum if there ever was one assembled together on one huge vessel. Certainly, there was more than room enough on this one. As tall as a New York skyscraper of that day, she was a city afloat, all the social classes present and working more or less amicably together to get to their destination, the New World's portal of New York, where they would part and, except for the super rich, never see each other again. Yet as sometimes happens with management at the highest levels, arrogance sets in, and just a tinge will do, impairing judgment and producing flawed decisions that, in the Titanic's case, proved just as fatal as it once did for the once mighty Titans who committed hubris and lost Atlantis.

Sailing full steam ahead to New York and, ignoring every warning, straight into an ice field...

Aboard the doomed liner a little girl in First Class lay in bed, troubled with a dream about people, some she could recognize, splashing about in nasty cold, icy water, screaming, while her nanny sat beside her reading a naughty French novel of romance in a Gothic castle.

Kiowa sages recorded the Great Canoe's sinking on their cowhide calendar.

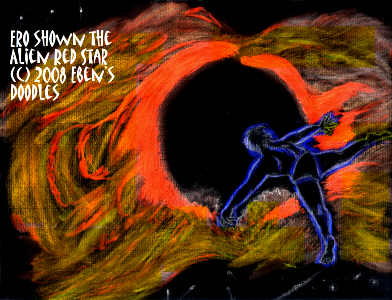

Ero the Cybernaut also gazes into the devouring mouth of the Red Star:

In its path, planets and stars and entire galaxies are consumed by the red-flaming star:

CHRONICLE ONE, PART I, VOLUME I, FATAL CONVERGENCE, RETROSTAR

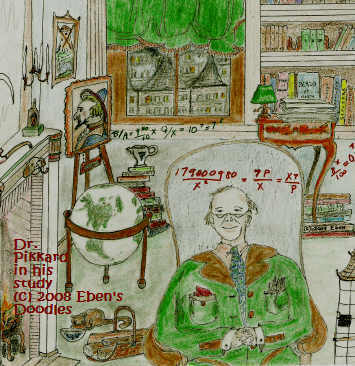

Dr. Pikkard, Dutch Genius/Retrostar's Cosmic War Challenger # 1

At certain points in the war, Dr. Pikkard's greatest creation, the intrepid e-butterfly named Wally, is the lone combatant:

Our RetroStar Chroniclers:

Gabriel Tall Chief, confined to bed in a children's hospice the remaining days of his CP-shortened life, shone like a pure blue star of heaven (which is awarded to those who fall in battle) in a red-star-dominated world. Which was more powerful? Only time and events will tell:

Gabriel's disciple and dream-weaver and dream-rider, Horace Brave Scout, who gathered the "fragments" of the chronicles that remained after Gabriel died and made a great leap for mankind.

Horace Brave Scout playing "Amazing Grace."

The Series of the Twin Earths is available on disk or can be electronically transmitted. The series consists of: RETRO STAR, Vol. 1, Fatal Convergence, Vol. 2, Cloud and Avalanche, Vol. 3. Battles of the DUBESOR, Vol. 4, Lost Chronicles; Part Two, Unchronicles, Vol. 5, Natal Convergence, Vol. 6, Beyond the Rapture, Vol. 7. Final Wars...Convergence at Orion

A "Letter to Agent, Outlines, and Overview and Marketing Strategy" of the Series":

Agent Letter, Outlines, Strategy

A Last Word Count in ANNO STELLAE 1997: 1,400,000

Outlines for VOLUME I, RETROSTAR:

CHRONICLES 1-24--WHAT'S IN THEM?

CHRONICLE ONE--WHAT'S IN IT?

CHRONICLES TWO TO SIX--WHAT'S IN THEM?

CHRONICLES SEVEN TO NINE--WHAT'S IN THEM?

CHRONICLES TEN TO TWELVE--WHAT'S IN THEM?

CHRONICLES EIGHTEEN TO NINETEEN--WHAT'S IN THEM?

CHRONICLES TWENTY TO TWENTY-THREE--WHAT'S IN THEM?

CHRONICLE TWENTY-FOUR--WHAT'S IN IT?

OUTLINES, CHRONICLES ONE TO FORTY-FIVE

OUTLINES, CHRONICLES FIFTY-EIGHT TO SIXTY TWO

Main Game Players (Earth II):

1. Ever wondered why the Titanic was named that? It wasn't the luxury liner's colossal size alone, her namesake was The Titans (Atlanteans) who lost Atlantis, on both Earths; then tried repeatedly to re-assert their rule over Earth II; they are a superhuman species that has turned vampire and lives almost indefinitely. Their major downfall, besides arrogance that led to hubris, was constant in-fighting and power struggles as this claimant and that claimant for the throne duked it out, with no gloves and no holds barred.

2. The Ten Stones of Fire (Starlike, Jeweline, Super-intelligent, Alien Entities), each performing as OP, or, Opposing Player, with the aim of conquering and destroying the Earths, I and II, and their respective universes.

3. Dr. Pikkard's Computer Wargame, represented by Wally, an electronically-created, free-roaming butterly who fights for humanity's survival against the Alien(s)

4. Human "Alphabetic" or A-Z Champions, also a subgroup called DUBESOR, or the Rosebud Champions

5. Yeshua, the A and Z, the Alpha and Omega, and the Aleph and Tau (also known as FC, the so-called "Forbidden Category")

EVEN BEFORE THE TITANIC'S SPECTACULAR MAIDEN VOYAGE DIVE TWO AND A HALF MILES DOWN IN THE NORTH ATLANTIC TO THE EDGE OF THE ABYSS, RECORDED IN CHRONICLE ONE, SOME CLUES ARE GIVEN US. FOR INSTANCE: ON BOTH EARTH I AND EARTH II A CERTAIN CHOICE OF A YOUNG RUSSIAN ARISTOCRAT'S FIANCE (UPPER CLASS, KREMLIN-BORN AND BRED DAUGHTER OF A COURT PHYSICIAN, KNOWN LATER AS ONLY THE "OVERLY POSSESSIVE" WIFE OF THE NOBEL PRIZE-WINNER COUNT LEO TOLSTOY) PREPARED THE WAY OF THE ALIEN ENTITY ON EARTH II AND THE DRAGON ON EARTH I: FOR THIS CHECK OUT SCENARIO I. THEN RETURN FOR SCENARIO II, WHICH REVEALS THE GREAT RECORDER HIMSELF, CHRONICLER GABRIEL TALL CHIEF. FINALLY, SCENARIO III, WHERE A KREMLIN STARETZ (PROPHET) REVEALS YEARS BEFOREHAND WHAT IS GOING TO HAPPEN IN THE ILL-STARRED 20TH CENTURY OF BOTH EARTHS, WHEN SOMETHING WORSE THAN THE H5N 1 STRAIN OF THE BIRD FLU VIRUS IS INFECTING THE TWINS, SO THAT THEIR INTERTWINED FATES ARE ALMOST IMPOSSIBLE TO SEPARATE FROM EACH OTHER.

RETROSTAR CHRONICLES:

RETROSTAR CHRONICLES DIRECTORY

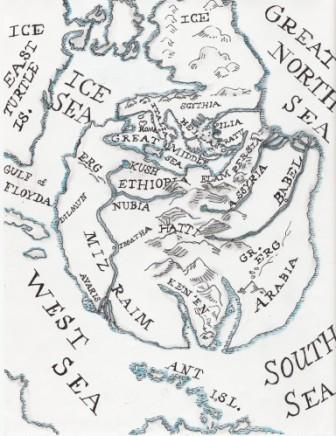

Earth I's supercontinent, which may have contained all the continents which presently exist:

Earth II's lost first civilization, Mukalia, and its continent:

Earth II's Mother Continent, Atlantis II, after the Re-Location of the Planet:

UNCHRONICLE OF THE HEAVENLY RUNEBOOK, Vol. IV, Retrostar

Like the Arab Muslims of the 7th Century, they seemed unstoppable on the seas, they were so superbly equipped, trained, and yet absolutely barbaric, they regarded no man's laws but their own. Dane-land was, for one major group of them, the wolfish mother, a breeder for the most powerful and rapacious of the whole race. Small, but ideal for sheltering and hiding their fleets, the northern land across from Britannica birthed tens of thousands of ferocious fighters called Danes. With ax, sword, or bow and spear, they could, man to man, take on any armed soldier anywhere in the world.

Becca the Red was one of the best fighting Danes, bear-shirted, with a lion's mane, and barely turned twenty, but already an accomplished hunter adept with bow, sword, and ax, which Danes had to be to be taken aboard a warship outbound for battle and prey and booty. Dane-land was a small place, without great forests and plains or much farmland, and far too crowded of late, so many cast eyes westerly and sought their fortunes and livings elsewhere, wherever defenses were weak and not too wary but the people rich, and the isles of Britannica was just what they were looking for.

Most people acknowledged, that Becca's grandfather was the most sagacious of men. Even wise men came to talk to him, seeking counsel in matters small and great. Chieftains and princes also came, since they were invested with weighty affairs of state regarding whole districts. As for the Danes' king headquartered at Hedeby, in regard to the expeditions of war fleets for raiding and plunder that sallied forth from there, an official came one day and returned to the king with a sour expression, bearing Mimir's counsel which said all the king's plundering of neighboring folk would bring nothing that would not turn to ashes in his hands one day.

An old wise man who did not toady up to a king? That was some brave man! Didn't he value the head attached to his shoulders? It was no wonder that some of the more thoughtful younger men visited him too. Becca the Red did not have to be told by other men how wise his grandfather Mimir was. He valued his grandfather greatly, and sought his side as often as he could spare from hunting, practice-fighting, sporting and gaming, building for pay on the chief's fleet of dragonships, and other manly pursuits.

The greatest of the king's plans centered on Lindisfarne, or the Holy Island. Lying hard off the coast of the King of Northumbria's domains, the island was the seat of St. Cuthbert's Church and monastery, the wealthiest in all the Saxon kingdoms of the British Isles. Having long eyed that glittering treasure-hoard of the Christians, but keenly aware how powerful the Northumbrian king was, the Danes conferred together as to how best to join their men-strength, weapons and ships to seize it. As their fleets grew in number and strength, the day passed when they were not assured they could match the Northumbrian king's forces with their own and win the prize. But, after hearing all the various strategems thrown out in the thick air of the king's grand feast-hall, some craftier soul among them had this cunning thing to say: "Hold, all you high chiefs and young, daring blades! Why fight the king? We need not risk our men and ships in battle with the Saxon dog? Why not sail our fleet on a suitable day of our choosing and take the Holy Island by surprise and carry away all we want from it before the king springs from his bed as he hears the first alarm?"

The crafty one prevailed, and the plan was worked on in secret meetings in Hedeby and elsewhere in chieftains' mead-halls all over Dane-Land. It so happened that Becca the Red took part in several meetings, as his father, Rasmus the Green-Eyed, took him along with him to learn how grown men deal with important matters. It was rather boring to the young Becca at first, but when he saw that the Danes were allied in the matter and were truly determined to carry the daring thing through, he realized it actually concerned himself and his own life, and he began thinking what his own part of it might be. Yet it troubled him deep within. He knew of an authority greater than his father in his family, namely his aged, very wise grandfather, and he did not approve of the growing number of raids on neighboring kingdoms and cities the Danes were making with their sleek and deadly dragon ships. Plunder, riches of gold, silver, and beautiful women for sale as concubines later after they were "broken in" at orgies, was indeed coming back, but not all the men--there was the rub to such ventures. Wives lost husbands, brothers, and fathers even, and mothers lost sons, and sisters their brothers. While some men and families rejoiced in the booty they gained by attacking some far city, others wailed and mourned their dead.

What gain is that? Mimir would ask. "If it were truly a good thing to do," he observed once to Becca, "there would be merriment for all in it, not sorrow mixed in as with the booty that comes from this raiding." Becca too lost an older brother, Ansgar, just that way. He recalled how his mother had wailed in their house, the sound piercing through the walls and into the village to the other houses, until a party of drinking men came staggering and begged his father to shut his wife up, she was spoiling their celebration of a successful raid.

Life went on in his family's house, but never the same, as the loss of one brother and son was hard on the others. His mother too seldom found anything to laugh at after that, and her eyes were most often downcast, dark and sad as she went about her household chores. The house was full of gloom, consequently, and Becca avoided it as much as possible, only coming home late at night to crawl into his bed.

So Mimir's wisdom acted as restraint on the young, budding warrior, Becca the Red.

To please his grandfather, Becca thought how he might appreciate more warmth in his clothes, so he hunted a bear, brought him down with an arrow and a spear thrust, then flayed the skin and pelt and had it made into a wonderful bear-shirt. Mimir had outlived two wives, and a slave woman was his only helper now, caring for his household needs. He might have married her, even though she was much younger, but he judged himself too old for a wife now.

"Why not take her to bed, Grandfather, to warm your bones at nights? You don't need to marry her and give her your goods when you die. They can be buried with you or burned in a funeral pyre. And she is young enough to still give a man pleasure."

Mimir shook his head. "I will not force an old man's love on her. She is content to serve me as she is, my son. And I am content with her as she is. We get along just fine together, so there is no need for any change. I won't last too much longer anyway. I feel a chill strangeness creeping into my bones-- like cold wind is blowing there, scattering my elements, whirling them away into the darkness. Someday soon, I feel, that strange wind will blow ice and snow upon my heart and the frozen pieces will separate and fly away like leaves from a tree!"

"No, no, Grandfather," Becca protested, "you'll live many days yet! Life is good, it is sweet to the taste--you don't want to taste the bitterness of death yet! You've scarcely put a sweat on beneath your new bear-shirt, and now you will put it off for a thin, cold, burial shroud? Please don't talk that way!"

The old man laughed, then turned very stern. "But you are young and foolish, and do not know the world yet and how it must face the coming doom, the Ragnarok of the gods! Everything we know in this wide, bright world is surely coming to an end. Everything! Why, mighty, cloud-piercing Yggdrasil, the wondrous Ash-Tree that upholds the Universe, whose topmost boughs go up to Asgard the shining abode of the gods, is being consumed even while we speak. An evil serpent and his spawn are busy night and day gnawing its root beside Niflheim, his home in the world of the dead, which will kill the tree and bring the Universe and all we see and know crashing down!"

Becca was appalled the first time he heard this, but what could he say? His Grandfather knew all about it, and he knew virtually nothing!

"So don't look to Thor's hammer or Odin the One-Eyed Rune-Reader," his grandfather went on, "the Frost Giants and the Mountain Giants who live in Jotumheim, who are the enemies of all that is good, will someday go to battle against the divine gods, and their brute force will prevail and conquer. Asgard will be destroyed, Valhalla of the dead heroes will be destroyed, and all the broken, defeated gods driven into whirling darkness to wail and wander forever."

Something in Becca's heart and soul would not be placidly, hopelessly resigned to fate and rebelled, resisted the awful, inescapable judgment that his Grandfather described. But he had an immense difficulty that mocked him. He had nothing from his little store of wisdom and knowledge with which to counter his Grandfather's dreadful words, but still he pleaded with him.

"Is that the utter end? Isn't there going to be anything good come of it--just darkness and ashes and death?"

His Grandfather paused, rocking back and forth in his bear-shirt, muttering old verses of a wisemen and skalds who had combined them into long songs about gods, heroic deeds of men, and ultimate doom for all after the defeat of the gods.

In his thin, quaking voice, he began singing a few verses he still remembered about the end of the Universe:

"The sun turns black, earth sinks in the sea,

The hot stars fall from the sky,

And fire leaps high about heaven itself."

Squirming where he sat on a carved stool, Becca was beside himself, and wanted to run out of the room and lose his tormented thoughts in hunting some boar or bear, but he tried a last time.

"Oh, Grandfather! Is there no hope for us Danes at all? Surely, you know of something! Surely the gods would not leave us bereft of every last reason for living and drawing the breath of life into our lungs! What are these mighty gods and all their powers for? Balder, Freya, Frigga, Thor, Odin--are they altogether vain and useless to us?"

Mimir the Sage heard his distraught, favorite grandson, knew that the Northmen's gods were indeed useless to men in the last extremity, but paused, took a shuddering breath, and his eyes closed tightly, then sprang open and shone like two sparks from the hearth fire, singing:

"In wondrous beauty once again

The dwellings roofed with gold.

The fields unsowed bear ripened fruit

In happiness forevermore."

Hearing this, Becca's heart surged, for in these ancient words the old ones had recognized there was, indeed, a hope, a promise, for the Danes to cling to amidst the catastrophe of the overthrow of Odin and Thor and the Universe of stars and moon crashing and dying in darkness!

But what did the wise old ones see? What exactly was it? He had to know or die!

Becca sprang to his feet, then knelt over his grandfather, putting his ear closest to Mimir's check as he dared, so he would not miss a single word of his response.

"Is there more they say, Grandfather?" he urged him.

His Grandfather's hand reached and seized his grandson by his fiery hair, almost wrenching it from the roots.

"Yes! One is coming, He is coming!" he croaked.

Then he sang:

"A greater than all.

But I dare not ever to speak his name.

And there are few who can see beyond.

The moment when Odin falls."

With these last words from an long-ago, long-buried sage or skald, the old man collapsed back, breathing heavily, and Ingmar his maid-servant hurried forward to bring a soft, damp cloth to wipe her aged master's sweating brow.

She looked up at Becca with pleading eyes, as he rose, backing away, not sure what to do. Was his grandfather all right? Or dying? But at least he had not left him in despair. He had given hope in the last fruit of his lips! Becca moved back away, and slipped outside, waiting a short while, then looked in and saw that his grandfather was resting, eyes closed, and breathing regularly. The maid-servant looked up at him, her face composed and relieved.

"Good Ingmar," he called to the maid-servant. "You are a helpmate for his last days. Take good care of him! Do not fear. I will see that you are taken care of well for it, when he takes his last voyage. I--I thank you, Ingmar, for this service to my grandfather!"

Her eyes glistened, and she bowed her head to him, then returned to her watching her master.

Becca stood, amazed by his own words. What had he done? Thanked a servant?-- a mere slave who had been carried off to Dane-land years before in a raid, from some foreign land she had probably forgotten? Yet he knew he could go now, and not be worrying, with Ingmar (her Dane-given name) tending Mimir. With a whoop and shout almost of joy, he ran off, scattering the folk out of his path as he made for the open fields.

It was only in the wilds of a wood he paused to catch his breath, and then he thought. "But who is the coming "Greater Than All"? What would be his name?" His Grandfather had failed to say, or the skald's verses he was chanting were not complete enough to tell him. He saw he must return soon to find out if there were more verses that would resolve his puzzle. If only there were runes carved on big, tall stones that recorded the name of this "Greater Than All" and told his exploits. He would have to search for them in Dane-land. But in the meantime, he was out to do some hunting, and the stalking of a particularly noble, many-pointed buck soon swept any bad thoughts out of his mind that could have spoiled such a beautiful, bright day as this one was.

In the following days, Becca continued his regular pursuits, though the meetings increased concerning a coming expedition that involved all the ships combined that the Danes could muster. Being of fighting age, he was not exempt and had to attend, so he went and listened to the older men discuss the matter concerned. The king was involved directly in its details, which meant it was bigger than the chiefs' usual raids. What could be bigger? Lindesfarne, the golden prize of Northumbria, of course! Everybody knew that, though no one dared to speak about it openly in public.

Danes, great lovers of pleasure and ease and indefatigable boasters, could be extremely tight-lipped when they had to be--to keep the important matters of state from slipping into the ears of enemy spies sent to their forest camps and waterside villages to ferret out what next was hatching in their chiefs' conclaves. They had paid dearly when some Dane among them had been too loose of tongue after drinking meed and ale too freely among his friends. It had happened that the enemy they had gone to raid met them prepared for battle, and they had been worsted. No, they had to have surprise on their side, before the whole citizenry was aroused and came running with their weapons to drive the Danes back to their ships. Silence on the subject in public! Secret meetings! That was the key to any raid's success.

So Becca also said nothing to others outside the meetings the chief called about both the meetings and the matters discussed. All that outsiders could see was the feverish activity taking place down at the yards of the dragon fleet. What the cause of that hive-like activity was, they could only guess. And even if they had heard that talismanic name, Lindesfarne, it did not matter so much. They still could not know when the expedition would take place, or how many would go, and other such critical details. To learn them, a man sworn to secrecy with a blood oath would have to break that oath and later pay with the public butchering of his wives and daughters and sons before his very eyes before his eyes were put out with smoking firebrands. Then his skin would be flayed, piece by piece, in the famous way they had, excising rib by rib, until finally his lungs were exposed and then were pulled out of his living body and draped around his neck! So far nobody had ever broken that oath and the dreadful punishment had not been exacted.

Oh, it was clear that the Northumbrian king had many eyes and ears, some of them Danes well-paid for the service, but nobody in the clandestine meetings divulged a single item. As weeks stretched into months and the year drew toward the celebration day of the Birth of the Christ Child, the king and his court grew tired of the matter of the impending attack, and set little store in it. The Danes, just as well informed by their own network, knew the main force of soldiers stationed at Lindisfarne had been withdrawn back to the king's castle, and few left behind for them to deal with. Many, both Danes and Northumbrians, thought the expedition to Lindisfarne was even called off, for the good reason it was thought too daring and the weather normally too stormy at that time of year. For all anyone knew, the cunning Christian monarch, the Northumbrian king, would be laying a cunning trap, waiting to pounce on them when they showed up on his coasts. Wouldn't the Danes' fleet be sailing right into the mouth of a lion and be utterly devoured?

Despite the frequent meetings taking much of his time now, Becca saw his grandfather often as he could, prizing the moments with him. He could see the strength fading in the old one, day by day, yet Mimir's mind remained strong and his spirit fearless and unconquered by approaching death, just as a great veteran warrior's should be, Becca thought. If only he knew runes-craft and could carve on stone his grandfather's sayings! he thought. As it was, he had to memorize them, hoping he wouldn't forget one. They were all wonderful sayings of wisdom, and deserved passing on to the young Danes playing in the streets, lest they grow up ignorant as beasts.

The best way, he found, to draw him out like drawing water from a deep well was to ask him things and get his responses.

So he asked him, "What is the chief prize that Dane men should seek?" He expected to hear wealth, women, booty, many strapping sons, and a fine ship for raiding, followed by a stately burial in a longship sunk into a lake, with women mourning and tearing their hair, and the warriors burning it and singing chants about his great deeds of war. But his grandfather replied:

"A man knows nothing if he knows not that wealth begets an ape."

That came as a shock to a wealth-worshipping, young Dane! But he continued. "Is war bad for a man, fighting a vain thing, and the sword a snare for him who holds and wields it?"

Mimir: "A coward thinks he will live forever if only he can shun warfare."

Feeling a bit better after hearing that, Becca proceeded.

"Drinking makes the heart glad, and puts shine in the eye of the lover and the one he loves, and looses the latch of love; besides friends are friendlier, and everywhere there is laughter where the mead flows freely. Is drink from the drinking horn the gift of the gods to us men?"

Mimir: "There lies less good than most believe in ale for mortal men."

The grandson was checked by this, for it recalled to Becca the many evils he had already seen come of drunkeness in the village--the wife beating, the servants abused by their masters, the crying children who could not escape their father's mean kicks, and other such things that too much drinking, not to mention the hunger it brought when everything was spent on ale instead of food, while the master lay sodden on his couch with his mead cup refilled all day by cringing slaves.

Becca thought of asking other, more pleasant things instead. "I have heard a skald laugh and say, Life is not but a fool's game, a jest, that's all! It is wrong to take it so serious. We are all the offspring of some merry god's jesting."

Mimir responded: "A paltry man and poor of mind is he who mocks at all things."

Again, a bit shocked to hear that even gods might be mockers and poor and paltry of mind, for if a god mocked men, then that would also be wrong even if he were a god, but he went on. "If not wealth, or much ale, or a big ship, or the other things, then what is the better prize for a man to hold in his heart?"

His grandfather did not hesitate. "I once was young and traveled alone. I met another and thought myself rich. Man is the joy of man. Be a friend to your friend. Give him laughter for laughter. To a good friend's house the path is straight, though he is far away."

How pleasing such wisdom was to Becca's mind! He was encouraged to ask more. "Can you trust the nature of a man?"

Mimir: "None so good that he has no faults. None so wicked that he is worth naught."

"Who can we trust most, man or woman?"

Mimir: "In a maiden's words let no man place faith, nor in what a woman says. But I know men and women both, and men's minds are unstable toward women."

Becca mulled over that for a while. It seemed that it needed more thought at another time. In any case, it counseled him not to prejudge a man or judge him too harshly if he did err or wrong him in some way, and be especially careful when he sought to place his faith in someone.

"Will we be judged for our wrongs someday?"

Mimir: "Cattle die and kindred die. We also die. But I know one thing that never dies, judgment on each one dead."

"The secret heart of a man? Where is it? Who can know it?"

Mimir: "The mind knows only what lies near the heart."

When the old man's eyes closed, and Ingmar drew up the beautifully dyed and woven woolens, taking a stool by the bedside to watch him for the hours of the night, then Becca withdrew and went out to let him rest until the next time. In the meantime, he recited what he had heard, over and over, commiting those wise sayings to memory. The sayings were like pure gold to him, better than gold, since he could carry them anywhere and no one could steal them!

He still had some gold left over from his earlier days as a performer in much demand-- hidden away deep in a particular tree's clefted trunk. So what did he need of other gold? he thought. Besides, his father would just take his earnings and rewards, if he ever performed again for the chiefs and the king himself.

How popular he had made himself before his father went and brought him home for good-- afraid that the wealth he was being given for his dances, singing, and fire leaping would draw robbers to his house if Becca continued to entertain in the mead-halls.

Becca sighed at the memory, how four years before he had performed before the king in the great hall at Hedeby on Jutland's coast. Built on a lake at the head of a fjord, the town was ringed by great ramparts of earth and timbers sunk deep in the earth, and the port was a forest of mooring masts, as cargo ships from all over the northern world came to trade. With over a thousand souls, Hedeby was the biggest city Becca had ever visited, and the king's mead-hall was jammed for the event of his performance with hundreds of warriors, nobles, and the king himself and his retainers and officials.

Becca stopped by his home to pick up his hunting gear and a bow and went to see if there were some game birds for the table down at the nearby marshes along the river.

He got off some shots at several wild geese in the water, but the breeze off the water miscarried them and he only wounded one, then let them go and wandered up into the woods to see if he might flush any gamebirds there. One bird with so little meat wasn't worth trailing with a good, long swim, so he wasn't interested in pursuit of it.

His grandfather preferred venison over gamebird anyway. A nice young doe would be very tasty in the stew Ingmar would make for old Mimir--as his few teeth were not much good for chewing steaks these days!

As he crouched low with his bow and made his way carefully through the shrubs and bushes the deer preferred for forage, he thought of the performing he used to do.

Perhaps the hour was too late, for as time passed no deer came out to forage on the shrubs, so he decided to wait in the woods for the early morning when the deer would surely emerge hungry and not so wary as in the dusk.

He found a big, old log, pulled enough of it away at the side to be able to crawl into it, then pulled the wood down to create a blanket for him. Here he knew he would be warm and dry enough to pass the night hours. He slept, dreaming of his pleasant days as a performer before great men.

The king liked his fire leaping so much, executed with a battle-ax, that he couldn't get enough of it seemingly. After he leaped it, then he would bring the battle-ax down on the embers, casting thousands of sparks whirling upwards, as he gave battle cries and leaped, swinging the ax beneath his feet.

His sword play, clashing the swords together as he leaped, gained him a lot of applause and cheering.

His singing of riddles was also much demanded, despite the jealous professional skalds looking on critically and remarking he was stealing from their riddle-hoard, but what they said was not true, he knew plenty riddles his grandfather had taught him that the king's skalds and jesting fools hadn't even heard. But his enactment of the death of the most beloved god Balder was the most popular. He first sang the verses about the Balder, brought about by the devious Loki, who used Balder's blind brother and a dart of harmless mistletoe. Loki had directed that brother's dart to pierce Balder's heart, for the mistletoe was the only plant on earth that had not sworn to do Frigga's son no harm. The warriors used their black shields to carry him to the shore, then he was taken by a small boat to the pyre-ship, and then the ship was set aflame, though he was really still safely aboard the boat).

The king and his entire court and all the celebrants with him went out to view Balder's pyre-ship burning. This event was a costly one, indeed, for the ship was not a derelict. It was a very valuable ship the king kept in his own fleet, that was still seaworthy and could have been sent on raids but was sacrificed expressly for this grand event.

The reenactment of the Balder tragedy was a great success and the king was vastly relieved, as it had cost him greatly in the loss of a fine fighting ship. Becca instantly became more than a clever gymnast and a skald combined, he was seen as a hero to the king and the people, who represented the the greatest story they had in their long memory of past events. Becca was given a king's ring, a bag of gold, two cows, and ten sheep, with a nobleman's cape besides! He could have asked for a royal bodyguard position if he had thought of it and gotten it.

Later, returning home with all this treasure and the cattle pulling the cart carrying the sheep, enjoying the wild acclaim of his village and the admiration of all the women along with the envy in the eyes of the men, he found all sorts of messages coming, by boat or by courier on horseback--entreating him to come to various places all over Dane-land and even in farflung Norway.

It was then his father, seeing the pile of these important messages with the seals of great chiefs and even a royal seal of the king of Norway at Trondheim on one of them, put a stop to it, gathering the whole lot and casting them into the hearth fire.

"I can't let you go again!" he declared to the stunned Becca who dashed to sweep the messages from the fire, but couldn't save them. "This has got to stop now!"

Becca had been beside himself, understandably. He had done so well, the cheers of the warriors and nobles in the king's mead-hall still resounding in his ears, so how could he stop, when all the world seemingly wanted to see him and his cunning arts.

"No, father, I cannot disappoint such important and powerful men! I must go to them!"

This made his father very angry. "I will not have my youngest son, after losing one older, be lost in turn! If you grow rich, and you will grow very rich at this rate, while still living under my roof, I shall not sleep one night in peace, for fear of a band of robbers breaking in and murdering all of us for the gold!"

Gold drew robbers as honey drew flies! Everyone knew there was sense to what his father said, and Becca wisely withdrew quickly and nursed his disappointment in the woods by hunting. He came back when he was good and ready a day later, dragging the hindquarters of a buck on a makeshift sledge and the many-pointed antlers strapped to his shoulders.

His father, who had been worried that he might not return home at all, was greatly relieved and also pleased with the buck. After that, there was no argument, for his father would hear not a word more about the matter, once he had decided it. Besides, it was his house, and his father's word was law.

Thus it was in the land of the Danes, and Becca knew that as well as any Dane. He still had regrets and misgivings, since he knew he was missing the excitements of the larger world outside his own village, but it could not be changed--not while he was living at home and too young yet to set up on his own.

It wasn't easy for his aspirations to be crushed so early in the tender, green bud, but somehow he endured it without angry words with his father, which would have done him no good and perhaps some lasting harm if he raised his own hand against his father.

He could not forget how his father had once seized him by the shoulders, his voice choked as she said: "You have my eyes! You have my heart also! If I let you go, and you did not come back alive to me, I would perish too. What are your brothers to me now? You are more to me than all of them! They care only for their own things--not like you, you are different from them."

Different from his brothers? Howso? Yet as he thought about his brothers, he saw the difference his father may have been talking about. After they had gone on raids and returned, they had changed. Twisted--that is how they were, just like the twisted oak of Grandfather Mimir's staff! Before the raids, they had been brothers, running and doing things together, always together. It was such joy to be with his brothers then. They hunted, swam, raced, and played pranks together on the village folk. They were punished together too when caught. Nothing could separate them then! Yet later, when they went off on the ships, he was too young to follow, and the first time he felt separate from them, and it was a bitter thing, but he still hoped he would grow up fast and join them, and everything would be as before.

Yet things never did change back to what they had been. His brothers returned, and were like strangers to him--cold, distant, aloof, even superior in attitudes. They wouldn't tell him what they had done, and refused to do any more household chores, dumping them on him and the servant Tiggard. It was a disgrace to be treated like this, but he had to bear it, and Tiggard--he was even beaten if he didn't obey them fast enough as they lounged about the house at all hours of the day, feasting and drinking up their earnings from the raids.

Once he had found his brothers taking turns dunking poor old Tiggard's head into the rain barrell, until he was half-drowned. How they had cursed him, their own brother, ridiculing him when he pulled Tiggard away from them. When he went and told his father how Tiggard was being mistreated, his father sighed. "It can't be helped, son! They are grown men now. They can use their numbers to beat me too, if they so decide. I can't take a sword against my own sons, they know full well, no matter how bad and boorish they behave in my house and toward my household. So what can I do with these beasts whom I have fathered? All we can hope is they will grow tired of their life here and take their earnings and build houses of their own. Then we will have peace under this roof--only then! If they go on raids, let them! Only you-- I thank the gods you were born years after your brothers, so that I wouldn't lose you so soon!">

Becca, as if he were set like a clock, awakened promptly before dawn, and crawled out of his sheltering log.

He was rewarded for his vigil, for there were the deer, five or six plump does in the herd, picking at the shrubs' buds while the buck stood somewhere near in the trees out of sight.

He soon had his doe, and carved out the choice, tenderer portions his grandfather could deal with best, including the inner organs that made such good stew stock when cooked with lentils, onions, lingonberries, and savory herbs.

Hurrying homeward, he went straight to his grandfather's and found Ingmar already up and going about stoking the fire and getting the utensils out for the morning meal. He brought in the deer meat, and she smiled at him, and took it gladly to fix for the old one's first food of the day.

Would he be eating with his grandfather? Ingmar asked him. "Later, I may return for a some portion of it," he told her. "But take all you like of it, whatever he doesn't want." Leaving his grandfather's lodge, Becca returned home, then remembered, going to check the notches he made on a wall of the house, that recorded his age and the months he had lived. He saw, notching the last day of the month, that he had now reached his birthday. It was time for him to claim a match for a berth as crewman on a raiding ship!

Months before this year dawned, he began to think afield again. He was a man and wanted his own house, wife and family. He had his secret hoard of gold, but he would need more. That would soon be gone. Why not volunteer on the raids that were going on increasingly, now every year in fact? If his father would release him to fight, he could win some plunder and no one could take it from him--not even his father--as it was accounted a warrior's personal property, and no village chief or his own father could take it away. Law protected it. He could take it to his grave and have it buried with him, if he so chose.

So he applied went to his father even before he had eaten his first meal, and asked him. His father did not protest, seeing it was his son's year to come of age. He replied to Becca he knew a captain that was related to them, but even with that relation he had to submit to a test of his fighting prowess and strength against a battle-proven warrior. Was he ready for that? his father asked him. Becca nodded, and so it was decided: his father would go to the captain and a testing match would soon be set. It could even happen that very day!

Becca had excited thoughts as he ate breakfast with his father and brothers, and his mother and sisters serving. It was almost too much to think about and eat at the same time. His brothers had lately warmed up to him and were already discussing the coming match, and counseling Becca how best to fight with sword and the battle-ax, and other particulars they had never seen fit to discuss with him before. Of course, they assured him, the warrior would not slay him if he failed to not fend him off with shield and swordplay, but he would suffer disgrace and maybe not be taken on a ship if the captain thought he did too poorly and wasn't worth the risk.

"Better to not test than to shame and disgrace our family and our father's name," one of Becca's brothers declared. Becca's hair rose from their roots, but he held his angry words back, as he realized this brother was no equal to the one they had lost, and spoke without knowledge and was no great warrior himself, having been turned down by two captains before he succeeded in getting on a third ship, but only because it was under-manned and desperate to make up fifty for the oars.

Becca kept his own thoughts. He had prepared for this, long in advance, in truth. Training himself with all his weapons in turn, he mastered them, but he still was unsure how well he would do when the real test came. He knew he could shoot with the best and hit his quarry, but it was swords and battle-axes that decided a fight man to man.

He was taller than most Danes of his age, but not so broad in the shoulders as many older ones. He could run swiftly as a deer, but that did not help him swing for swing of the broad-ax or sword against a war shield. There it was the force a man could put into the blow, that often decided the match, he knew from times watching the various prospects being tested for the warships.

But he knew he had more wits than most men. Could he make them serve him so that he could overcome the broad-girthed warrior? So he had observed the matches with keen eyes as captains tested the applicants for their crews.

When the time came for his own match, he felt he had a good chance, having seen the weaknesses of being too big were about equal to the weaknesses of being too small. He was in between the two, and was both strong and swift. Surely, that would prove an advantage, if he used it with cunning and the right timing.

Meal over, the family and the others of the same clan met, discussed Becca's testing, and decided to go together to the event on the day set. But first Becca's father needed to speak to the captain. He left and soon returned, informing everybody it was indeed today, the captain was impatient to get his ship manned, and was wasting no time! Down to the ships! he ordered Beca, his brothers, and their brethren followed.

Near the waterside, with the dragon-headed prows of ships ready for sailing casting shadows over the waterline and sand, the match was arranged.

The applicant, Becca, and his opponent and testor, were called to present themselves and their weapons, and they both left their assembled brethren and curious other villagers and stood in the center of the small crowd.

Then for the first time each man took the others measure.

Pitted against a big, broad-shouldered, big-bellied warrior, Becca saw he had the perfect antagonist to test his green willow of a theory.

But the man was dangerous, a war veteran who did not give quarter. It either worked this time, or he was finished, for this man--Ivar Hairy Breaches-- was not known for treating anyone kindly who failed to fend him off. In fact, despite what his brothers had told him back at the breakfast, he would kill and finish the job with taking his head too for a belt trophy, if he wasn't hauled off a man.

By this time, planks were pulled out of the lumber piles and set up so the two clans could sit down.

Knowing Ivar's reputation, Becca's father and brothers sat down to watch, all grim-faced, knowing that this was the supreme test of Becca's manhood. Would he succeed or would his head with its flaming red hair end up dangling from Ivar's iron-studded belt?

Becca's family was prepared to fight Ivar if it came to that, but they could not, would not, stop the testing, as this was the immemorial way of the warring Danes, to insure their captains good, fighting crews. Without high quality maintained, the crews and the ships would never return from the long and hazardous raids across the stormy sea waters.

Sitting on the planks laid on crewmen's wooden lockers, their swords drawn, facing Ivar's clan who were seated with their swords also drawn, the two clans waited. The two men were taken with a man carrying a battle horn a short distance, where they each briefly knelt before a wooden image of Thor and one too of Odin, and then they returned, the horn was blown, and the battle was begun, as the captain looked on.

The testing did not take much time. All that was required was that a man, either the applicant or the testing warrior, was shown weaker than his opponent, or too poor in swordplay and liable to be killed if he kept on, and the match was called off with a sign from the captain to the man with the horn, who blew a blast and ended the event.

Everybody present knew, of course, that Ivar was too thick-headed to remember such niceties. He was like a big black boar of the thick swamp oaks, who lunged out at passing warriors, no matter how many were hunting him--it did not matter how many arrows he took, he kept fighting and slashing with his tusks. They knew that even the gods might not be able to save the loser of this match, since Ivar was in it and he knew no mercy.

Becca and Ivar, their weapon of choice drawn, circled each other, as everyone held their breath. Both held shields too, and Ivar had chosen to drink too much mead too, and was in a berserker-like frame of mind, with much snorting and fuming and rumbling of his throat. Suddenly, bellowing the Dane war cry Ivar lunged upon the younger, slighter man, intending to split him head to crotch with his sword, as he had done to many a man in the raids.

Becca whirled aside, letting him pass, slip and slide in the sand, then faced him, jeering Ivar with special taunts he knew. Snorting and rumbling, Ivar came rushing at him again, and Becca seemingly vanished, leaping aside at the last moment.

Ivar Hairy Breeches found he was slicing thin air, but rushed onward, then stopped, shaking his head and turning around with a bewildered expression. Everybody present, including the captain, could see that Becca could have easily followed and caught Ivar in the back of his head with a thrown ax, but had held off to wait for Ivar to regroup. Somehow, he refrained from calling the match by having the horn blown--this was just too good a match and spectacle to stop, and his own fighting instincts overruled his good sense.

Ivar meantime was doing some hard, if not fast thinking, apparently, as this had not happened before to him and he realized he had to do something differently if he were to catch this elusive Becca with his man-splitter.

He moved more slowly and carefully toward Becca, keeping his already narrow eyes focused on him like two traps on the same quarry. Just before he reached arm's length from Becca, Becca sprang back like a deer, which brought Ivar's immediate plunge forward and the Dane's bull-like war cry. But when Ivar swung the sword, where was Becca the Red?

He had flipped his willowy body and vanished in thin air! What witchery was this? Dumbfounded, Ivar felt a tap on his head, looked up, and saw the blade of a battle-ax suspended over his head.

The dozens of villagers and clans of Ivar and Becca erupted, all shouting at the same time and scrambling to get near the champion and touch his red hair for good luck, and Becca was carried on the shoulders of his brethren, rejoicing all the way, to the proud ship he was to sail.

After congratulating the young warrior, Captain Soren was most pleased to show him his oar and seating, and then explain his duties, which were all guaranteed and spelled out according to the law of the Danes governing ships and crews and plunder.

Poor Ivar, skunked so badly by a mere youth, slunk away with his own brethren, cursing Becca, but unable to understand what had happened.

"It is witchery!" he protested. "That saucy red-head, I tell you, cast a spell on me!"

Now Becca already knew the strict laws he agreed to obey in order to man an oar on Soren's ship or any such ship and to follow the captain unquestioningly as his commander on any raid taken. Among them, no fuel or quarrel was to be taken aboard or allowed on board. No woman aboard either. And any news or reports went directly to the captain. If any captives were taken in raids or war, they were to be brought to a meeting stake or pile, and there sould and divided according to rule. A man's war booty was his own, and his kindred did not have a right to it, he could take it to his grave if he chose. Simple rules, for the most part! Tried and true rules! They kept peace and maintained order aboard ship, with fifty crewmen and captain and sometimes thirty more crammed in if necessary, warriors or captives. All were as good at the helm as they were at the sword.

As for Soren's ship, close inspection and a tour of it with the captain pointing out various items showed Becca it fitted the standard admirably. He was proud to win a place on such a fine vessel. Broad and shallow, it could sail as easily up any creek as it could on the storm-tossed sea. Seventy six feet from stem to stern, and sixteen oars a side, each either 17 to 19 feet in length, all beautifully shaped and fitted through round oarlocks cut in the strake, with the holes fitted with shutters that closed when the oars were shipped.

Sixteen strakes a side of solid oak planks, she was fastened together with tree-nails and iron bolts, and caulked with woven animal hair cord. The strakes, fastened in this manner, could glide like a serpent across a choppy sea, and not take on water, though the strakes were so flexible, able to take the pounding of the seas and not break up as other, more rigid ship hulls did in severe storms at sea.

With pride Soren demonstrated the large wooden rudder and its wooden movable tiller, fastened to the hull with a cunning wood piece that gave the blade full play. Since Becca's father had special way with fashioning these rudders and tillers and the most cunning part, he had been kept busy making them and was well paid enough to stay in the village and in his home, without having to make raids to earn something more as he grew older. That is how Becca did not need Soren's instruction, for he already knew the secrets of the special rudder and tiller the Danes' ships carried.

Becca's heart was thrilled with the thought of their soon launching of the beautiful dragon-headed ship. The sight of their war shields, ranged for alternating colors of black and yellow along the sides, along with the dragon prows jutting out into the water, had thrilled him since he was a little boy hanging about the shoreline watching the ships come and go from the little port. Now he was going to sail on one of them as an oarsman!

This particular raid did not require much provisioning for a long sea voyage. They knew they would find plenty provisions where they were headed: Lindisfarne, the Holy Island. It lay directly across the northern sea between Norway and the big Saxon island.

They knew this venture was established by the king's command, and there was no turning back now from the venture, as the ships were all ready and accounted for. They sailed on a certain date known ony to the captains, the chiefs and the king. They only had to obey when they heard the summoning horn blast, and run to the ships with their weapons and whatever they wanted to carry along in their individual lockers aboard ship. Becca returned home for his things, then went quickly to see his grandfather, and told him he was tested and approved and was a crewsman on Soren's ship.

The old man was hoarse today and his speech slurred returning his greeting on this visit, Becca found. Mimir's eyes were closed, and he wasn't sure his grandfather was awake as he gave his news to him.

"We're going on a raid very soon, Grandfather!" he told him. "But I will be back with some gold from the raid for you."

"Lindisfarne?"

"Yes, who told you!"

Mimir's lips curled slightly, as if he were about to smile. "A raven can fly in the king's great hall and learn many things there and then go and tell the other little ravens. That is why the king must beware of even birds in the rafters of his mead-hall!"

Becca laughed, but was still puzzled, and wanted to know how a bird had told his grandfather.

"If the raven has flown to your bedside, Grandfather, can you tell me when we will sail?"

Mimir smiled this time. "Tomorrow, before dawn."

Becca was scandalized and looked around, seeing only Ingmar busying herself with sweeping in the house and seemingly paying them no attention. Had she somehow found this out and told his grandfather? That was a fearful thing to do, to tell the king's secrets, even if it was to his grandfather!

"Don't worry, my boy!" Mimir croaked. "If you do not sail before dawn tomorrow, I will tell Odin's raven not to come again to this house and whisper tales to this poor old man! In fact, Ingmar may just clap him into one of her meat pies! Wouldn't he be tasty!"

Becca chuckled at this, and then he left, for he saw his grandfather was now sleeping, his mouth gaping open in the way of old men sleeping.

Returned home, Becca sat and worked at polishing and sharpening his sword and battle-ax. He had time to think about the soon coming venture too while he worked. When he was satisfied his weapons were in order, he packed a few things--sharpening stones, an extra knife, some arrowheads, a chipping knife to make more arrows, which he wanted along in a wooden locker handed down to him from the few items not buried and belonging to his lost brother. Cautioned by his father, he laid in some dried vennison too, with smoked, salted codfish and herring, he might need it if they didn't find enough provisions after all, if the king of Northumbria should meet their flotilla with his own and force a long, hard battle on them, whether at sea or on land. Drinking water would have to be had aboard ship from the captain's stores. His mother gave him an herb for staunching bleeding from a wound and another herb to purge it of evil taken from the enemy's blade or the arrowhead. There were some cloths to wrap and dress wounds too.

When he had checked everything and seen that they were were satisfactory, and even his father was pleased with his preparations, he went and lay on his pallet, for he wanted to gain an extra hour or two of rest, just in case. After all, it had been a big day for him, the testing, to be followed shortly by the launching, if his grandfather's little bird was telling the truth!

He rolled from his pallet and sprang to his feet, his heart pounding. He heard the second blast of the horn, and knew what that meant--"To the ships on the double!" He had his things laid close by his bed, and so grabbed his locker and weapons and without giving any word to family or to his father he made for the door and was surprised when it opened to him, and his father faced him.

This was something his father had never done before, he took Becca in his arms. "Don't do anything so that I will lose you!" his father whispered into his son's ear. "I never told you, you were always my favorite son, and my heart would stop if I heard you were lost too! Do your duty, fight well for your captain and your ship, but come back alive! Alive!"

Too astonished to know what to say, Becca pulled away, then ran for the yards.

A hundred ships sailed in the flotilla that targeted the Holy Island, Lindisfarne, and all its treasures. The various fleets met at a prearranged point off a chosen island, and then sailed westerly toward the Northumbrian coast.

Storm or good weather, they were not to be deterred from their objective. Previous days had seen sheet lighning, and much thundering of Odin's hammer striking a shield, but now calm had settled across the northern world. Stars had even fallen, and other fearsome signs as well. Yet the calming prevailed. Spies had reported to the king that now was the best time, as the monks' Christmas celebration was concluded, and the island would be jammed with the offerings brought to it by thousands of pilgrims who sought the blessing of the St. Cuthbert's bones in the great church on the island.

Moreover, their delay had put the Northumbrian king off, and he had recalled his main forces to deal with some raids from the Picts and other tribes of the far north. He was certain the Danes would not dare to anger his God by attacking on his holiest days of the year, when there was so much rejoicing in the birth of the God's Son. Even the heathen, idol-worshiping Danes were not thought capable of that much impiety.

The crew aboard Soren's ship was like the others, and did not think much about these matters, which were left for the captains, chiefs, and the king to deal with. Instead, they worked like a team together to make the voyage as quickly and uneventful as possible, quick to perform each duty as best a man could. Many had not eaten since the night before, but there was no grumbling, not a word. The captain brought out some food from his stores, and this was shared, and they kept up the work without pause. The wind was brisk, and the waves choppy, the wind blowing the wave tips into their faces, but no raging storms yet to test them and the ship. Perhaps Thor and Odin would favor them with good weather all the way! it was hoped.

Keeping in sight of each other, the fleet moved toward Lindisfarne. When they first sighted it, the tall church tower was standing above the waves, with the causeway to the coast the Pilgrims used twice a day invisible under the high tide of water.

They all knew they would strike just at dawn, when

it was best to catch the unwary by surprise.

For all they knew, when they rushed from the ships

and ran up into the village and the churches and

monasteries that thickly covered the island's

northern half, they would catch the abbot and

his monks and even the guards still asleep in their

beds and dormitories! They would make short

work of them then!

Already, it was decided what each ship's crew

was to do. Soren's crew would send at least twenty men to

run in first, and attack and subdue the guards of the

king stationed on the island. There were many

pilgrims residing with the monks in the big

dormitories and even in the small, conelike

dwellings, these might be armed, but the soldiers

would be dealt with first. Soren was one picked

by Captain Soren for this duty. The other thirty men

would be sent to the big dormitories and the

stone huts. After they had

gotten the pilgrims and monks, selecting out

the best younger ones for sale, they could join in with

the sacking of the main edifice and the various storehouses.

Altogether, the fleet provided about 4,000 warriors

for combat and transport of valuables afterwards back

to the waiting ships,

and not all these would be needed, if the

Northumbrian king was not hiding a force somewhere of

ships that would attack them while they were

taking and sacking the island. To

deal with this threat, since spies had been known to

give false information before, some of the fleet was

detached to guard their own ships while the men were

on land raiding the monks' treasures.

The hours passed as the fleet waited for the

right hour, and no storm brewed and

hurled waves and winds at them.

The attack vessels, Soren's among them,

moved in, and then drew up by the shoreline with

a lightly falling surf. The men leaped out and

pulled their vessel up on the sand partway.

There were no coves or a creek to sail up, so this

would have to do for a few hours. As long as

no storm struck, the ships would be

not be in jeopardy.

Organized on the beach by their captains and

commanders, they were given the final order, and

they ran silently toward the sleeping

Christians in their tall, grand, stone and masonry buildings.It was too dark as yet, so

they then moved slightly south of it, to the lee

of the island's highest point, a mount of bare rock, and

waited, in the hopes that no watchman was

standing duty there to give warning of them. They also

hoped no storm would blow up and

seriously endanger the whole fleet and the expedition.

It was dark, and they also counted on not being spotted

by any patrols sent out by the Northumbrian king. Perhaps they would be lucky, and the

king's eyes and ears would be shut, as they slept off the

effects of the glad celebrations of the days before.

Becca and his fellow crewmen found the guards' huts and the battle began. They had little difficulty, as the men were mostly asleep or groggy, and were killed, most of them, struggling out of their beds as they reached for their weapons too late.

Next the pilgrims and monks! There was less difficulty here, and the monks bore no arms at all! Only a few Pilgrims carried swords, and fewer still drew them in time to defend themselves. The Danes swept through the dormitories and the stone huts, and left them littered with bodies. Some captives were rushed together at a collection point, and later they were sent back under guard to the ships, for division and sale at the stake if there was time for that. Otherwise, they would have to be divided when they returned to Dane-Land, and that was not so desirable, as relatives might have other ideas who got what.

Even while the sacking was going on, buildings were set afire, as the Danes always preferred to leave nothing standing if they could help it. Why? It was just their old custom, to level the the sites they raided. But there might have been this practical reason too. It made it easy then to tell if the people, if there were survivors, had returned after all, if the buildings rose again. Othewise, the ruins could fool a ship at sea, and hold nothing for them for the trouble of going to look.

Custom or for practicality in a raider's cynical book, burning always created a great deal more terror and confusion, which helped them in their efforts to completely subdue any opposition. If the terror was great enough, less resistance. Cowed Sheep were thus easy to manhandle and slaughter. After all, they hadn't come for the fighting, they had come for easy plunder.

Since this was Becca the Red's first raiding expedition, he was normally excited and did all that a young warrior was trained to do--without much thought about it. It went so quickly and well, and he dispatched the guards, then turned with his comrades to deal with the pilgrims and the monks.

It was only when it came to dealing with the monks that Becca felt something, a bad feeling, enter his heart. The monks were young and old, and the young ones quickly taken for sale as slaves. But what to do with the old ones? Soren ordered them slain, with no delay.

As Soren went away to join the other captains and commanders in ransacking the big church and the storehouses, Becca was left with his men put in his charge now to dispatch the monks. The pilgrims, he had slain without thought. Why should the monks be a problem for him? They were nothing but strangers and aliens to him--Christians worshiping an alien, invisible God, whose only image was the Son of the God, called Christ. But when he raised his ax over the first in line, an old man who looked like a grandfather to him, he thought of his own, and hesitated. That hesitation was fatal. He could not make himself bring the ax down and split the man's head wide open. Why? He had caught the look from the man's eyes, a glance of an old man upon a young, foolish man about to do some very bad, shameful deed. It smote him in his heart, and he drew back, letting his battle-ax fall.

His comrades rushed up, all talking at once. What is the matter? they wanted to know. We are to hurry with this lot, they reminded him. We have much to do yet to get all the goods to the ships along with the captives, they said.

"I can't kill these old priests in the robes," Becca muttered, backing away. I joined to fight soldiers, soldiers who bear arms, not old men who bear nothing, who bear only those crosses round their necks! It disgusts me to kill harmless, old men like wretched chickens or sheep! They are more than that!"

His men were shocked, but one or two were angry, and shouting. "The captain will deal with you! He will hear about this!"

"Go, run and tell him then, if you are such low animals!" Becca hurled back at them. "Tell him I am a man, Becca, sent to fight men, not little chickens and sheep! Give me men, armed men, and I will gladly fight them, man to man. These, never! Never!"

By this time, he was shouting so loud, that it was amazing they did not start fighting each other.

But then Soren came running partway toward them just as they were about to start a blood-letting of Danish blood, and knowing nothing about the trouble, he called to Becca to come and join him in sacking the great church. Becca turned to the men, and some stepped forward after taking a look at the old monk Becca had spared, and he ran with them to Soren, while the others who remained dealt with the remaining monks according to Soren's orders.

The awesomeness of the church, even during the raid, was beyond anything the raiders had encountered before in their lives. Nothing in Dane-land compared. They lived in hovels, their king's mead-hall fit for only a kennel of dogs in comparison with the magnificence rising pillar upon pillar, hall upon hall, to a soaring roof that touched the sky!

But they were here for business, not sight seeing and standing around with their eyes wide and their mouths agape! In the church, the men were surprised to find it so vast and full of great halls and all sorts of staircases and levels, with furniture of all sorts, and even stairs that led down below the church into crypts and secret storehouses. While Soren and other commanders and captains were seizing the altar's golden cross, saints' reliquaries, also gold but encrusted with jewels, and the rich brocades of the curtains and draperies, while smashing whatever they did not want to take with them, Becca and his men ran up to the next level.

There they came to a door set in a long wall, and Becca chopped it open and swung the doors wide. He burst into the great hall and found strange things, indeed. It was full of work desks, stools, benches, writing tools, and cabinets full of books, all very large and full of mysterious Christian runes.

No gold, so they were not interested in the contents of the big chamber, and started almost immediately to hack everything in reach to pieces and throw things through the tall windows, smashing out the translucent panes of fine glass.

Some Danes seized the huge books and began ripping out the pages, for a fire they started right in the center of the chamber.

Becca saw a book being ripped apart, and he grabbed a couple leaves and looked at them. They were completely a mystery to them, of course. But he had seen nothing so fine in all Dane-land, the lettering so perfect and regular from line to line, page to page. It was most amazing to him, the craft and cunning that had gone into this rune-book of the monks, and now his men were burning what must have taken years of the monks' labor to write and bind together.

Whether he had thought it out or not, he felt he had to save some of the book closest to hand if he could. He grabbed a big section of the leaves, snatching them before the fire could ignite them, and stuffed them into his bear-shirt for safe-keeping.

Then he went and left the chamber, but thought to look through a small door into an adjoining cell, and there he found some young monks, scribes perhaps, all crouched down in the shadows, their writing tools scattered around them.

He dragged several out, and saw that they were indeed monks, but the young ones that the older ones trained in schools. He pulled out one leaf of his book fragment and thrust it at one boy, and ordered him, in Danish, to read. Read!

The boy could not understand Danish, but he knew what the red-haired Dane wanted, and trembling, his voice shaking, he began reading the lines as he pointed to the words. Hearing him do this, Becca was satisfied he had what he wanted, and he had an idea too. He took the boy and pointed to himself, saying his name, Becca. Several times he did this, then he pointed to the boy, and waited. The boy understood quickly, and said, Aelfric. Becca repeated the name, so he would remember it and the boy's face, and then he and his men herded the boys out as captives.

Since the writing and book room held had no gold or any valuables the Danes could want, and the smoke was now thick, they departed it and left it to burn. The captives were taken to the square for transport to the ships. Downstairs, and in the underground chambers, there was still a lot of valuable things to discover and take away before the flames made it too dangerous to remain there.

Becca found Soren and the others had completed the sacking of the main sanctuary, and so it remained only to run through the underground cells and chambers to see if they wanted anything from them.

That accomplished, Becca and his men, together with a hundred or more others from the other ships, left the building just in time as the roof started aflame, and the entire edifice was being consumed end to end.

Meanwhile the storehouses had all been looted, carts loaded up, cattle yoked and made to pull the carts, and stores of every kind of food, drink, fine clothing, bedding, furniture, golden treasures from the sanctuary, all were transported to the ships, with the captives driven there too on foot after the unsuitable ones, those too big or able to fight back, weeded out with a battle-ax laid to the skull.

Still, the king, when he was certain what he was up against, would have to call out his main force to deal with them, he couldn't just send a few hundred men he had on hand after sending so many soldiers to deal with the invading Picts. This king was too crafty for rash actions like that. He would first muster as large a force as he could before he moved against the sea raiders. How long would they have till the king knew for certain Lindisfarne, his holy island and St. Cuthbert's, was taken and sacked by a very large fleet? It would be only a couple hours, at the most. So they had to move quickly to the ships with the booty and captives, load them aboard, and set sail for home!

The monks' trainees were taken to the shore along with the other captives, and Aelfric waited for whatever would happen to him, his hands bound behind him. He watched the biggest boys killed with ax blows, but the smallest ones too were also dispatched. Was he too small? No one came for him, and he thought he might live, but then he wasn't sure. What if he and a few others around him were to be killed, and they just hadn't gotten to it yet. He felt this must be the case, and was certain he was doomed. He began praying, for there was nothing else to give him any help or comfort. The Danes, he knew, were pagans with no sense of mercy for their captives. They destroyed everything they did not carry away, for the sheer joy of destroying fine things. They were nothing but barbarians, and so that was all they knew to do. He felt sorry for them, but they terrified him more than he felt sorry for them. Only one of them had made him give his name--what did that mean? As he waited for some Dane to come and kill him with his ax, a flame-haired Dane moved closer, inspecting one captive after another.

Then the big Dane with the lion's mane of red hair falling down his face and over his shoulders came to him, and called his name. He answered, and the man grabbed his arm, hauling him to his feet, and then made him walk toward one of the ships that stood drawn up partway on the beach.

When they got to the boat, a bearded, older Dane jumped down to stop them.

Aelfric watched the two Danes begin to argue right there on the beach, and the older man glanced a time or two at Aelfric. The men waged a fierce battle with their words, while each held a clenching hand on his sword as if itching to draw them out for battle.

Upcoming episode:

As Becca sensed, and wise old Grandfather Mimir hinted from time to time, there had to be something more than just plunder that lay as the motivation of the raiding Danes, particularly as they were always attacking Christian kingdoms and Christian lands. For centuries they had heard of the Christian God and His Christ, and had ransacked enough churches and Christian dwellings to know what the cross signified, that this Christ of the Christians had died on a Roman stake in an earlier age, and had made himself thus a sacrifice for men's sins. Missionaries had come, indeed, to their lands to teach them this very message, but they were either run off or slain on the spot. After all, they had their great, noble, fearless, and concubine-rich Northern gods, and did not want to change them yet, as their gods were giving them such great success in their long-boats on the raids they conducted year after year. Their gods paid well to believe in them, so why convert to Christianity which preached penance, piety, and purity? So they remained in their religion and were satisfied with it, for all their lusts were accounted for and indulged. Only were they satisfied?

The ferocious way they treated the Christians they captured in battle and the way they dealt with the cities and towns, churches and monasteries and schools-- that spoke of how unsettled and unstable they really felt deep inside their northern hearts. All the time they felt something was missing in themselves and in their religion, but what was it? The increasing contacts with Christian things on their raids reminded them, like cold slaps of sea waves in the face, that they lacked one essential thing, which nothing they won by bloody conquest could fill. They hauled home beautiful women captives and fine clothing and costly crafted things from towns and cities and the plunder, sacks of gold, jewelry, and coins from the sacked monasteries and churches and towns and villages they overran, but all the Christian wealth they could desire did not satisfy. In fact it had the opposite effect, it reminded them of their own inner poverty and starvation of the soul.

So, the wealth angered them, spurred them on to greater ferocity than before. Wolves to begin with, they took drugs and much mead before battle, and wore bearskins and became "berserkers," becoming so enraged with blood and violence that they would bite off ears and rip their victims with their teeth like savage animals.

They weren't merely out for plunder, they were out for revenge and to utterly destroy the civilization and the Church that offered them something they were denying, while feeling the pangs of utter soul starvation gnawing within and rendering them hollow men.

That denial, that flight from the answers that Christian faith provided for men's soul hunger and yearning for God and salvation, fueled their rage and lust and sent them again and again out from their northern bases to hurl their longships, swords and battle-axes in lightning raids upon the innocent, and sleeping Christian townships and communities round about Dane-land and spread across the farflung isles of the Saxons and Britons.

Eight year old Honorius Urbanus and his distinguished father made a special trip all the way from Glevum in southwestern Britannica to Roma, the ruling capital of the world. It did not start so auspiciously, however, after they crossed the water and traveled through barbarian- ravaged Gaul. Even northern Italia was just as broken up.